(1)

Hand Surgery Department of Clinical Sciences, Malmö Lund University Skäne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden

Abstract

Our hands are essential to us. We take it for granted that they will always be present and ready to intuitively execute our intentions. The hands are intelligent and full of silent knowledge; they remember what they once have learnt. In body language they represent much of our identity. The hand has been called ‘the outer brain’ and ‘the mirror of the soul’. The hands have a special link to the soul. Their ‘language’, gestures and expressions reflect our mood, whether it is joy, disgust, despair, surprise, thoughtfulness, disappointment, wonder or hope. Hands can appeal, help and welcome. With our hands we can threaten or deny and express empathy and sympathy. We use them to applaud and express approval, wonder or shame, and we can convey quantity and size.

The hand has a rich symbolic value in religion, art and philosophy, but hand gestures may have completely different meanings in different cultures. When the power and function of the hand is not sufficient, it can be extended technologically through a variety of tools such as levers, joysticks and mobile phones. In modern industry, the competence and creativity of hands have largely been replaced by machines and robotic devices, but the hands’ accumulated experiences and knowledge are still something genuinely human, giving the hand a key role in society and cultural life.

Our civilisation is primarily based on the knowledge, creativity, abilities and experiences of the human hand. The written word, beautiful handicrafts, a melodious piano piece – they are all a product of creative hands. Handicraft traditions have always constituted a basis for the design and decoration of articles for everyday use. Artistic handicrafts, sculpture and painting are all based on the creative power and silent knowledge of hands.

But we are living in a time when the ability and experiences of the hand are no longer appreciated and utilised as before: In many schools, teaching and training in handicrafts and woodworking are not given sufficient priority. Handwritten letters hardly exist anymore. Handmade objects are becoming more and more uncommon. Today, the hand’s abilities are most interesting for handling a computer keyboard, touching the icons on smartphones or handling joysticks to control computer games. In industry, computers have taken over the manufacturing of objects that in earlier times were the product of skilful and sensitive hands.

The late architect Peter Broberg wanted to create an Academy of Hands to take advantage of and safeguard the knowledge and capacities of the hand, with a focus on the handicraft traditions that are still maintained in the area of Österlen in the county of Skåne in southern Sweden. Such an Academy would arrange courses, symposia and seminars addressing subjects associated with the creativity of hands. Several fields and subjects would be represented, such as artistic handicrafts, fine carpentry, blacksmithing, textile art, painting and sculpture, and invited lecturers would discuss and demonstrate the potential of the hand in music and art. Selected parts of courses in anatomy, physiology and neurology would also be included in the activities of the academy.

I think that such a hand academy should have a prominent place in the research community. Without hands, no laboratories would function, no research protocols would have been established and no dissertations would have been written. No computers would be built or used, and no Nobel Prizes would be delivered from the hand of the Swedish king.

Perhaps the hand could be regarded as a symbol of knowledge and understanding. According to the Bible’s story of creation, Eve was tempted, despite a very obvious prohibition, to use her hand to pick fruit from the tree of knowledge, to take a bite and then give it to Adam: ‘It was a delightful tree since it gave you sense and wisdom and she took from its fruit and ate; and she also gave to her man who was with her, and he ate’ (free translation, Genesis 3:6). The punishment was certainly severe – deportation out of Paradise – but the hand had forever conveyed a newborn knowledge to the first humans that was essential for the continuing development of man.

The anatomy of the hand is complex; its function is based on an interaction among muscles, tendons and nerves. But no hands would function without advanced interaction with the brain, so the hand academy would also pursue research into this interdependency. The hand has a cortical representation of its own in the brain and is constantly changing depending on the hand’s activities. If the hand is very active and receives high levels of sensory input, its representation in the brain rapidly expands and increases in size. A sensory experience may start with a touch applied to the hand, but the processing and interpretation of the sensory signals happens in the brain. What the hand feels is processed, perceived and understood in the brain.

Movements and gestures performed by the hand have their origins in the brain – the hand is the executive organ, the brain’s instrument and executive organ. So where is the beginning and the end of the hand? The hand begins and ends in the brain; the two organs constitute a joint functional unit. The hand has been called an extension of the brain, but perhaps we should also regard the brain as an extension of the hand – giving it access to our minds and souls.

The human hand has always fascinated poets, philosophers and artists. René Descartes (1596–1650) called the hand ‘the outer brain’, and Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) regarded the hand as ‘an extension of the human brain’, a link between body and soul (Fig. 6.1). Isaac Newton felt that the thumb was ‘a proof of God’s existence’. For Aristotle the hand was ‘the instrument of instruments’, a universal tool that can have several functions and can perform a variety of tasks.

Fig. 6.1

Le masque de Camille Claudel et la main gauche de Pierre de Wissant. Number 349, August Rodin, Musée de Rodin, Paris (Photo Christian Baraja)

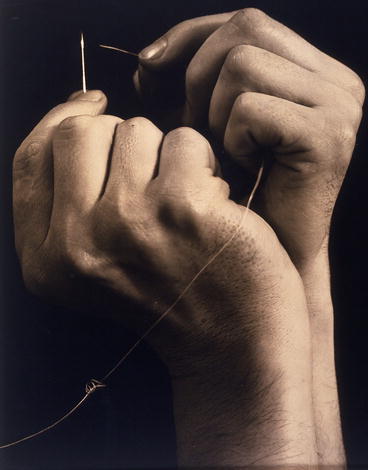

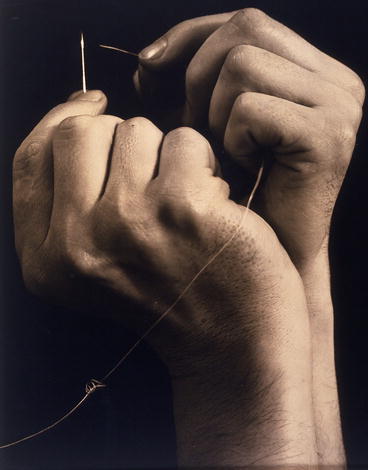

It is easy to become impressed by the hands’ repertoire: we are dealing with an instrument that can create a violinist’s skilful vibrato as well as a pianist’s virtuosic finger movements on the keyboard, or mix a pack of cards, throw a dart with high precision, handle a corkscrew, knead a pastry or open a Coca-Cola can. The abilities of the hand range from threading a needle (Fig. 6.2) to a knockout in a boxing ring. The hand can manage heavy lifting (Fig. 6.3) and can pick blackberries, rinse strawberries and peel potatoes, activities that require sensitivity, fine motor function and coordination. In a social context, the hand represents power as well as love and reconciliation. It can hit and it can caress.

Fig. 6.2

‘Threading the needle’ (Photo: Anton Bruel, 1929. Courtesy of The Buhl collection)

Fig. 6.3

A fisherman from Österlen in southeastern Sweden lifts the heavy catch of the day (Photo: Bo Balldin)

A Mirror of the Soul

The hands and the face are body parts that, in the western world, are freely exposed to the environment and that we like to decorate. In Indian henna painting, the hand is decorated with delightful coloured patterns, and we like to beautify our hands with rings and bracelets. Being a hand surgeon, it is easy to notice how hand cosmetics mean more to some people than to others: for an actor or a sales clerk exposed to numerous customers, the appearance of the hand may be very important, while others are more interested in the function of the hand than its appearance. In Sweden, the moose-hunting season is more or less magical for many hunters, and several times I have treated patients with hand injuries who refuse to remain hospitalised when moose season is approaching: They do not care what their hand looks like as long as the trigger finger works sufficiently to make shooting possible.

The appearance of a hand reflects much of its owner’s current living conditions, and their life and work experiences from past years; big hands with rough skin may indicate a hard life with a concentration on the hands’ force and function. It is usually easy to estimate an individual’s age by the appearance of their hands. An elderly face can feign youth with the help of cosmetics and face lifts, but the ageing of the hands cannot be hidden.

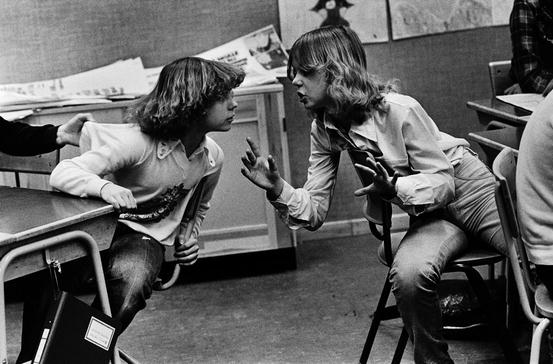

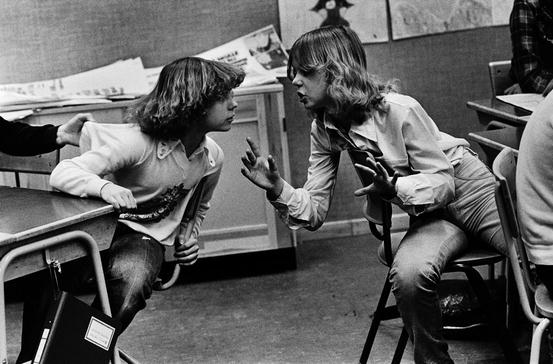

The hand represents much of our identity, not only by fingerprints but also in body language [1] (Fig. 6.4). Our hands, gestures and movements largely mirror our personality – even if the person’s external appearance changes with increasing age or sickness, she can easily be recognised by the way she gesticulates and moves her hands, something that does not change over the years. Identity and personality are mirrored in the handwriting and in every individual’s personal signature.

Fig. 6.4

The hand in body language. There is something exciting to tell – not to be discovered by the teacher. Stockholm (Photo: Jan Delden)

The hands have a special link to the soul; their ‘language’, gestures and expressions mirror what we feel, wish and want to express (Fig. 6.5). The hand and the face together mirror our mood – enjoyment, disgust, despair, surprise or fear (Figs. 6.6 and 6.7), thoughtfulness, disappointment, wonder or hope [2–4]. Hands can appeal, help and welcome (Fig. 6.8). With our hands we can threaten or deny and express empathy or sympathy. We use them to applaud and express approval, wonder or shame. With the hand we can indicate quantity and size.

Fig. 6.5

The hands are important to enhance our expressions. This man has something important to tell in the Maranatha tent in Stockholm (Photo: Jan Delden)

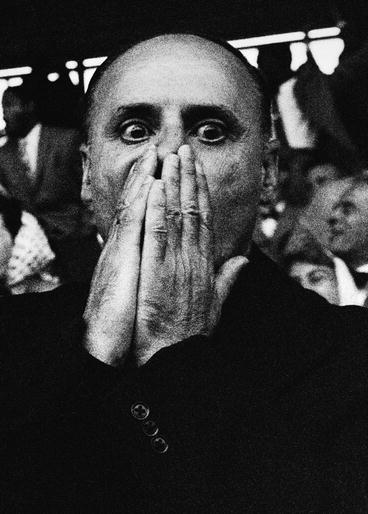

Fig. 6.6

Sweden takes the lead with 1–0 against Brazil in the FIFA World Cup final in 1958. The Brazilian official can’t believe his eyes (Photo: Jan Delden)

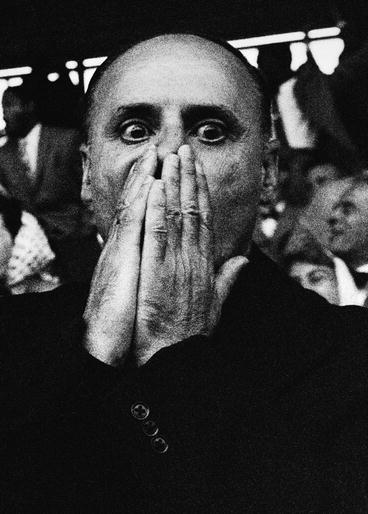

Fig. 6.7

Waiting for survivors. The sinking of the Andrea Doria 1956. The Italian ocean liner has sunk, and on the quay a crowd of people are waiting for news about survivors of the disaster. A nun gazes into the distance, pressing her hand against her lips and holding her breath – a gesture expressing both hope and fear (Photo: W Eugen Smith. Courtesy of the Buhl Collection)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree