Profile A: Mild overt and mild covert features

The duration of treatment for clients with Profile A is 5 months and requires 44 hours of treatment. Clients of this type are often children and adolescents brought to therapy by anxious parents. The goals for this kind of client are to reduce overt aspects of stuttering and, at the same time, in the case of children, to let their parents learn about and understand the disorder. This can help them develop a holistic understanding of their children, beyond their stuttering. Clients first undergo a 2-month period of individual speech therapy sessions. After that, they undergo a second period of therapy that lasts 3

months and requires 44 hours of treatment. Clients of this type are often children and adolescents brought to therapy by anxious parents. The goals for this kind of client are to reduce overt aspects of stuttering and, at the same time, in the case of children, to let their parents learn about and understand the disorder. This can help them develop a holistic understanding of their children, beyond their stuttering. Clients first undergo a 2-month period of individual speech therapy sessions. After that, they undergo a second period of therapy that lasts 3 months, which is accompanied by transfer activities. They do not undertake any art-mediated training.

months, which is accompanied by transfer activities. They do not undertake any art-mediated training.

Profile B: Mild overt and moderate to severe covert features

The duration of treatment for clients with Profile B is 12 months and requires 102 hours of treatment. This type of client is extremely anxious about their social presentation and possible negative consequences of their stuttering. Therefore, the treatment has several goals: (1) to increase knowledge and awareness of the disorder, (2) to increase the number and type of speaking situations into which they enter and (3) to modify avoidance behaviours and improve both assertiveness and self-esteem. Group activities are particularly important for clients with this profile. During the first 2 months of treatment clients undergo an intensive series of individual therapy sessions. Subsequently, individual weekly therapy occurs for 6 months. Transfer activities occur starting from the third month until the end of the programme. Art-mediated training occurs from 5

months. Transfer activities occur starting from the third month until the end of the programme. Art-mediated training occurs from 5 months onwards and lasts 5 months. Clients undergo an art-mediated training specifically for their profile.

months onwards and lasts 5 months. Clients undergo an art-mediated training specifically for their profile.

Profile C: Moderate to severe overt and mild covert features

The duration of treatment for clients with Profile C is 12 months and requires 110 hours of treatment. This type of client does not display any particular problems dealing with stuttering, even though the overt aspects of their stuttering are not mild. For this reason, the goals for their treatment focus on overt aspects of stuttering and providing them with effective behavioural tools that enable them to best manage their speech. Clients first undergo 4 months of individual treatment, focused on speech control. From this point onwards, individual sessions will support the programme once a week for 6 months. Clients undergo transfer activities after the first 4 months until the end of the programme. Art-mediated training is scheduled from 5

months. Clients undergo transfer activities after the first 4 months until the end of the programme. Art-mediated training is scheduled from 5 months and for 5 months subsequently. The art-mediated training for this type of client is movie dubbing for adults and adolescents and performed reading for pre-adolescents and children.

months and for 5 months subsequently. The art-mediated training for this type of client is movie dubbing for adults and adolescents and performed reading for pre-adolescents and children.

Profile D: Moderate to severe overt and covert aspects

The duration of treatment for clients with Profile D is 12 months and requires 124 hours of treatment. This type of client displays high levels of both dimensions of stuttering. For this reason, the goals of the therapeutic intervention are: (1) reduction of overt aspects, (2) transfer of fluency-enhancing techniques, (3) facilitating natural generalisation of these techniques and (4) reduction of avoidance reactions. Clients first undergo 2 months individual therapy, focused on speech control. From this point onwards, individual weekly sessions occur. From the third month until the end of the programme the clients undergo transfer activities. After 5 months from the start of their treatment, for 5 months they attend art-mediated training.

months from the start of their treatment, for 5 months they attend art-mediated training.

After clients complete their treatment, they are monitored during a follow-up period every 6 months for 2 years. This follow-up monitors both overt and covert stuttering features.

Demonstrated value

Tomaiuoli et al. (2006) published a file audit report of the outcomes of ‘a 12 months rehabilitation programme for disfluency integrating logopedic therapy and art therapy’ (p. 460) specifically consisting of movie-dubbing with 10 adults. Participants were tested just before the start of the treatment, 12 months later (when they had completed the ‘logopedic therapy and art therapy’) and 5 months later (when they had completed the dubbing component). Using the method of Campbell and Hill (1999), there was a reduction of 68% in the number of stuttered words from the first assessment to the final assessment around 18 months later. The participants were tested also with an adaptation of Schindler’s (1980) self-evaluation of verbal conditions. Mean scores on the Avoidance component of Schindler’s self-evaluation and on the Emotional Reactions component from the first to the last assessment showed a reduction of about 45%. Participants also were tested with Spielberger’s (1983) State-Trait Anxiety Inventory, just before the dubbing component began and just before competing the last of the dubbing sessions. Results showed a 31% reduction.

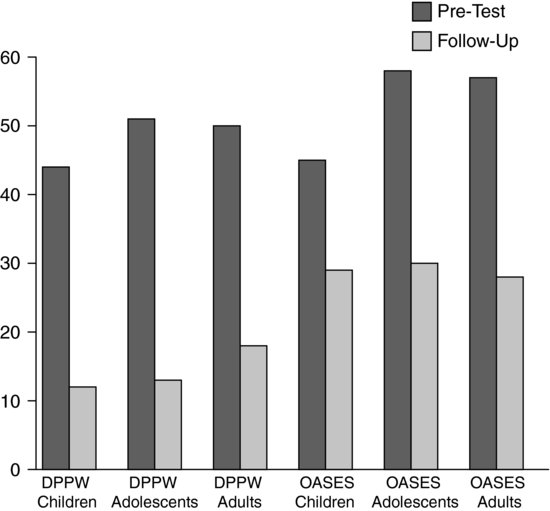

In the following text, we present data from a file audit of 153 of our clients. Figure 11.1 presents data from our standard clinical assessments (see Overview) using the Systematic Disfluency Analysis (Campbell and Hill, 1999)4 of within-clinic speech. Clients were treated for 12 months, and then follow-up assessment took place about 6 months later. The data presented in Figure 11.1 are pre-treatment and follow-up means of the reading, monologue and conversation tasks for number of stuttered words from a 200-word sample. Figure 11.1 shows a 70% improvement of overt stuttering features. Results for children and adolescents were similar at 73% and 75% improvement, respectively, while reported a 64% improvement for adults in the sample.

Figure 11.1 Mean pre-treatment and follow-up file audit data. DPPW, disfluencies per pronounced words; ACES, Assessment of the Child’s Experience of Stuttering; OASES, Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering.

Figure 11.1 also presents covert stuttering features pre-treatment and follow-up measured with the standard OASES (Yaruss and Quesal, 2006) or the version for children ACES (Yaruss et al., 2006). Figure 11.1 shows a 46% improvement of covert stuttering features. It is not shown in the graph, but improvement scores for children, adolescents and adults were, respectively, 35%, 49% and 51%.

Advantages and disadvantages

Advantages

The primary advantage of the MIDA-SP approach is that it provides an integrated and parallel approach to the overt and covert features of stuttering. It exposes clients to novel experiences, offering a stimulating and motivating approach to therapy. We believe that such a multidimensional approach favours the generalisation of acquired skills into everyday life. The treatment combines standard methods and methods personalised for individual clients.

Disadvantages

The disadvantages of the MIDA-SP programme are: (1) the long time it involves and (2) the related costs. In the case of children and adolescents who stutter, these costs are added to by clinician efforts to engage their parents.

Conclusions and future directions

During many years of administration and file audit testing, the MIDA-SP programme has appeared to be effective in consistently reducing both overt and covert aspects of stuttering. The treatment has been shown to favour the personal growth of the person who stutters using a holistic perspective. The programme format presented here is the result of many years spent working on its design, testing and refinement.

The next step will be its further refinement and evidence-based assessment. We plan that future research will reduce the duration and the cost of the programme but at the same time will preserve its effectiveness. We are studying two possible future treatment formats: a single period of therapy, shorter than the present, or a sequence of several shortened therapy periods.

Discussion

Mark Onslow

While the discussion groups were convening, the observers (see Preface for an explanation of who the observers were) watched some videos that we would like to play for the entire group. Francesca, could you explain the content of these videos briefly before showing them?

Francesca Del Gado

This is a short video about dubbing, which is an art-mediated training part of our programme, as we said. It allows us to expose clients to a favourite situation, but under time pressure. In fact, dubbing requires them to say specific words at a specific time during the movie track. In this way, clients can practice the use of breathing techniques, as well as fluency-enhancing and shaping techniques. Clients learn to express emotions through their voices and learn to modulate their voices in different ways. After that, they can say, ‘Well, I gave my voice to Robert De Niro!’

Now you will see one client who is trying to synchronise his speech with what Robert De Niro is saying in ‘The Godfather’. And here is a segment of that movie dubbed by a client.

Joseph Attanasio

Could you explain how you came upon the idea to use dubbing in your programme?

Francesca Del Gado

The ideas I am honoured to describe are Donatella Tomaiuoli’s ideas.

Joseph Attanasio

Could you also explain a bit more about what is involved in theatre?

Francesca Del Gado

We believe in the need to work on both overt and covert features of stuttering. Art-mediated training such as dubbing or theatre, or performed reading of tales, is useful to work effectively on both aspects of stuttering. This kind of approach is extremely versatile and gives the clinician a chance to personalise goals for each client’s needs. For example, if I know that the client has a particular difficulty with starting the first syllable of the first word, I can ask that client to dub a part of a movie that has a great deal of dialogue (and so many starts) to help overcome that problem. An important difference between using dubbing and theatre performance is that the latter enables clients to use their bodies as a nonverbal communication tool.

Joseph Attanasio

And for how long have you been doing this?

Francesca Del Gado

About 15 years ago, Donatella Tomaiuoli realised that clients can easily learn to use fluency-enhancing techniques, but this is not enough. We often experience how difficult it is for clients to generalise what they learn during their treatment when they are in their everyday life, when there is no therapist with them.

Joseph Attanasio

So, are you saying that art-mediated therapy facilitates generalisation?

Francesca Del Gado

Yes, during the treatment, which includes art-mediated training such as theatre or dubbing, clients accept that they have to expose themselves to situations in which they have to match the demands of everyday conversation. Clients’ perceived self-efficacy improves with facing a challenge, such as going on stage in front of a real audience and/or facing time pressure induced by dubbing in a recording studio. So, for example, when clients face an oral test at school, they think ‘I was on stage for a theatre performance’or ‘I was in a recording studio for dubbing’, and ‘if I did that, now I can do this’.

Ann Packman

How do you decide to move from speech therapy to the transfer activities, and then to the art-mediated training? Is it task mastery?

Francesca Del Gado

Yes, based on task mastery, we design a timetable for each profile. In our experience after 3 or 4 months of therapy, clients are ready for the next step. But steps overlap to some extent, so that skills from previous steps still feature in therapy but assume less importance with time.

Joseph Attanasio

This treatment is clearly driven by a view of what stuttering is. Could you just reiterate what stuttering is to you and how does it influence your treatment?

Francesca Del Gado

In our view the essence of treatment is never to forget that the client is first of all a person. Our multifactorial perspective recognises a genetic component, an attitude and an influence from the environment from client experiences. All of these are integrated into each client’s story, and as such require an integrated treatment. We don’t want to make clients think they will be perfectly fluent every time they speak. But we do want to give them the tools to enhance their fluency and the self-confidence to believe they are able to face every verbal situation of their lives, without avoidance reaction. We would like our clients to think, ‘So I stutter, but this doesn’t stop me from going to New York City’ or ‘putting up my hand in the classroom’, and so on. We also use irony and humour to teach clients to joke with themselves. This is particularly important in children, as they soon learn a positive way to perceive and cope with their stuttering, which is useful for each of their social interactions and for their growth.

Sheena Reilly

Could you give us more details of the fluency-enhancing techniques you use?

Francesca Del Gado

We follow the techniques outlined by Professor Hugo Gregory, because he inspired us. We focus on what clients need most. For example, if a client talks very fast, we obviously work on slowing their speech.

Sheena Reilly

So, you use different techniques on different clients?

Francesca Del Gado

Yes, each client experiences different techniques based on self-modelling and fluency enhancing. We introduce them all, discuss the clients’ points of view and then jointly decide the way to go with therapy.

Ann Packman

Our group thought that people from some cultures might not be willing to participate in theatrical aspects. Is theatre optional?

Francesca Del Gado

No, we can say we are not democratic with our clients. … But the length of our programme gives our clinicians time enough to build a sound relationship with clients, and obtain their trust and compliance. In fact, in the first period they do not often say ‘Oh, theatre is great!’ or ‘Oh, dubbing is great! I can’t wait to start’. Most of our clients say, ‘Please, please, I want just individual therapy sessions’.

Each group activity is difficult for our clients; they don’t feel comfortable with it. This is particularly true for theatre and dubbing, which are particularly challenging for clients who stutter. But as they go on with their treatment, they slowly change their mind about it. They realise that this training is important for them; that they are not alone in that activity, and there are clinicians there beside them during those activities.

Ann Packman

I think I would be reluctant.

Francesca Del Gado

Well, in such cases we say to our clients, ‘Take your time to reconsider the matter’. And usually they do it. They manage their worries and their anxiety. And after the play they often say, ‘I did it! I can do it again!’ Just this year, we had to schedule a rerun of the final theatre performance because our clients asked us to. If we look back at our entire experience, we can say that in about 10 years perhaps only three clients avoided this experience.

Joseph Attanasio

Could you tell us the youngest client that you work with?

Francesca Del Gado

Children can start this programme from the age of seven. But we also have a programme for preschool children.

Sheena Reilly

Do you involve the parents of the children? Do they come along to the sessions?

Francesca Del Gado

We involve parents of children and adolescents’ parents with counselling. We don’t usually involve parents in the sessions with children, because they often simply tell their children to not stutter.

References

Andrews, G., & Cutler, J. (1974) Stuttering therapy: The relationship between changes in symptom level and attitudes. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 38, 312–319.

Campbell, J. H., & Hill, D. G. (1999) Systematic disfluency analysis. In: H. Gregory (Ed.), Stuttering Therapy: A Workshop for Specialists (pp. 51–76). Evanston, IL: Northwestern University & The Speech Foundation of America.

Cook, F., & Rustin, L. (1997) Commentary on the Lidcombe Programme of early stuttering intervention. European Journal of Disorders in Communication, 32, 250–258.

Craig, A. R., Franklin, J. A., & Andrews, G. (1984) A scale to measure locus of control of behaviour. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 57, 173–180.

Gregory, H. H. (2003) Stuttering Therapy: Rationale and Procedures. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hicks, R. (2005) The Iceberg Matrix of Stuttering. Paper presented at the ISAD 2005. Retrieved from http://www.mnsu.edu/comdis/isad8/papers/hicks8/hicks8.html

Schindler, O. (1980) Handbook of Communication Disorders (Vol. I.) Turin, Italy: Omega Edizioni.

Smith, A., & Kelly, E. (1997) Stuttering: a dynamic, multifactorial model. In: R. F. Curlee & G. M. Siegel (Eds.), Nature and Treatment of Stuttering (pp. 97–127). Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

Spielberger, C. D. (1983) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press.

Starkweather, C. W., & Givens-Ackerman, C. R. (1997) Stuttering. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed.

Tomaiuoli, D. (2005) A theatrical approach to treating stuttering. ASHA Leader, 20–21.

Tomaiuoli, D., Castiglione, R., Del Gado, F., Falcone, P., Lucchini, E., Pasqua, E., & Spinetti, M. G. (2006) The use of movie and spot dubbing in stuttering treatment. In: J. Au-Yeung & M. M. Leahy (Eds.), Research, Treatment, and Self-help in Fluency Disorders: New Horizons. Proceedings of the International Fluency Association’s 5th World Congress (pp. 130–135), Dublin, Ireland: International Fluency Association.

Tomaiuoli, D., Del Gado, F., Porchetti, G., Spinetti, M. G., & Falcone, P. (2009) Tales interpreted reading: a laboratory for children who stutter. Paper presented at the 6th World Congress on Fluency Disorders, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Van Riper, C. (1982) The Nature of Stuttering (2nd ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Yairi, E. (2007) Subtyping Stuttering I: a review. Journal of Fluency Disorders, 32, 165–196.

Yaruss, J. S., & Quesal, R. W. (2006) Overall Assessment of the Speaker’s Experience of Stuttering (OASES). Journal of Fluency Disorders, 31, 90–115.

Yaruss, J. S., Coleman, C. E., & Quesal, R. W. (2006) Assessment of the Child’s Experience of Stuttering (ACES). Poster presented at the Annual Convention of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Miami, FL.

Woolf, G. (1967) The assessment of stuttering as struggle, avoidance, and expectancy. British Journal of Disorders of Communication, 2, 158–171.

1 This report is not published but is available to readers on request from the first author of this chapter at crc.balbuzie@tiscali.it.

2 The OASES is now published by Pearson Assessments as three separate versions for children, adolescents and adults.

3 This report is not published but is available to readers on request from the first author of this chapter at crc.balbuzie@tiscali.it.

4 This report is not published but is available to readers on request from the first author of this chapter at crc.balbuzie@tiscali.it.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree