(1)

National Center for PTSD and Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, White River Junction, VT, USA

(2)

Department of Psychiatry, Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH, USA

Although most research on the effects of traumatic exposure has focused on symptoms and functioning, a number of studies have shown that exposure to a traumatic event can have negative effects on physical health as well. For example, Felitti and colleagues (1998) investigated the effects of childhood trauma on adults in a large healthcare maintenance organization in the USA. For almost every disease category, individuals who had a higher number of traumatic events in childhood also had a higher likelihood of serious chronic diseases in adulthood, including cardiovascular, metabolic, endocrine, and respiratory systems. Although the investigators did not explicitly examine potential mechanisms for their findings, one explanation was suggested by evidence that childhood trauma was related to increased likelihood of poor health behaviors such as smoking and drinking.

However, behavioral factors alone do not account for the relationship between traumatic exposure and poor health. Instead, the most consistent factor is the development of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). This chapter reviews the evidence on the physical health consequences of traumatic exposure by using a model that conceptualizes PTSD as the primary mediator through which exposure affects physical health (Friedman and Schnurr 1995; Schnurr and Jankowski 1999; Schnurr and Green 2004; Schnurr et al. 2007b; Schnurr et al. in press).

5.1 Defining and Measuring Physical Health

Understanding the relationship between traumatic exposure and physical health requires understanding of what is meant by “health” itself. The World Health Organization (WHO) defines health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (http://www.who.int/about/definition/en/print.html, accessed 10/11/2013). This definition, reflecting a contemporary biopsychosocial perspective, actually appears in the preamble to the WHO constitution written in 1946. Recognition of health as a complex state thus has a long history.

Wilson and Cleary (1995) describe health as a continuum of increasing complexity, beginning with biological and physiological variables that represent disease or changes to physical systems. Next are symptoms, followed by functional status, health perceptions, and health-related quality of life. These elements influence each other but are not perfectly correlated and can be influenced by personal and environmental factors, e.g., two individuals with the same degree of pain may function very differently due to differences in temperament, social support, and physical exercise.

Both objective and subjective measures are needed in order to fully capture the continuum of physical health. These include not only laboratory tests, clinical exams, and archival records, but also self-reports. One concern about the use of self-reported measures of physical health is the influence of psychological factors such as negative affectivity (Watson and Pennebaker 1989) on how physical health is reported. In fact, comparisons between archival sources and self-reports usually find that self-reports are valid but not perfect substitutes for objective measures of variables such as utilization and diagnosis (Edwards et al. 1994; Sjahid et al. 1998; Wallihan et al. 1999). However, archival records are not necessarily perfect indicators either because they may be incomplete or inaccurate. Furthermore, although self-reports do not always agree with more objective indicators, an individual’s perspective is needed to obtain information about all parts of the health continuum except for biological and physical variables.

5.2 A Conceptual Framework for Understanding How Traumatic Exposure Affects Physical Health

Traumatic exposure is linked to adverse outcomes across the continuum of health outcomes: self-reported health problems and functioning (e.g., Glaesmer et al. 2011; Paras et al. 2009; Scott et al. 2011; Spitzer et al. 2009), biological indicators of morbidity (e.g., Sibai et al. 1989; Spitzer et al. 2011), service utilization (Dube et al. 2009; Walker et al. 1999), and mortality (e.g., Boehmer et al. 2004; Sibai et al. 2001).

In order to understand how exposure to a traumatic event could adversely affect physical health, it is necessary to consider what happens following the exposure. Direct effects of trauma are not the answer in most cases. It appears that relatively few trauma survivors are injured or made ill as a result of their exposure; even in a sample of combat veterans who were seeking care for a variety of problems, only 21 % had sustained physical injuries in combat (Moeller-Bertram et al. 2013). Also, the types of health problems that emerge—e.g., cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in civilians exposed to war (Sibai et al. 1989, 2001)—typically are not linked to the type of trauma experienced.

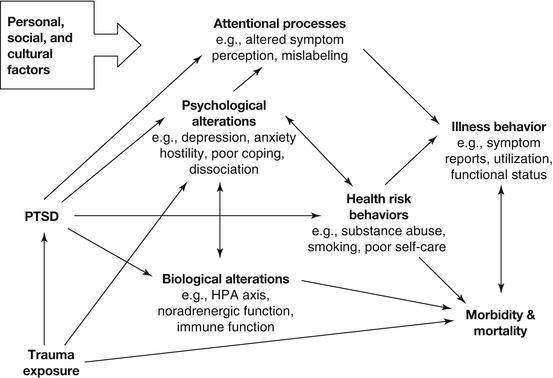

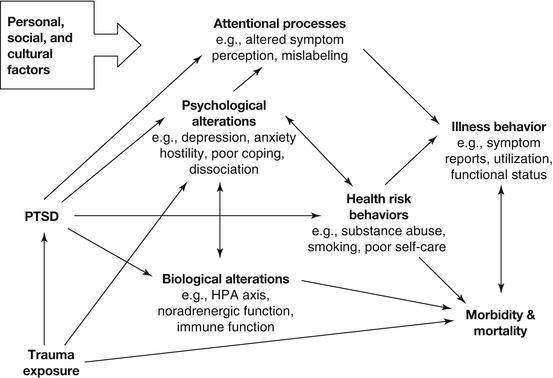

So if the traumatic event typically does not lead to direct physical harm, how does the exposure affect physical heath? Schnurr and Green (2004), building on prior work (Friedman and Schnurr 1995; Schnurr and Jankowski 1999), proposed that the answer is severe and persistent distress resulting from traumatic exposure—primarily PTSD but also other mental disorders (Fig. 5.1). The distress is necessary to engage psychological, biological, behavioral, and attentional mechanisms that can lead to poor health. This chapter focuses on PTSD because very few studies have examined the effects of disorders other than PTSD on physical health in trauma survivors. The focus also is on health problems that are not a direct result of a traumatic event.

Fig. 5.1

A model relating traumatic exposure and PTSD to physical health outcomes (From Schnurr and Green (2004, p. 248). In the public domain)

Psychological mechanisms include comorbid problems often associated with PTSD that have been linked to poor health. Depression, for example, is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and factors such as greater platelet activation, decreased heart rate variability, and greater likelihood of hypertension that could explain the association (Ford 2004). Biological alterations that are associated with PTSD offer additional mechanisms, e.g., increased activation of the locus coeruleus/norepinephrine-sympathetic system and dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal system (see Friedman and McEwen 2004). Behavioral mechanisms are health risk behaviors associated with PTSD, such as smoking, substance abuse, poor self-care, and lack of adherence to medical regimens (Rheingold et al. 2004; Zen et al. 2012). Attentional mechanisms could affect both health perceptions and illness behavior; for example, Pennebaker (2000) suggested that avoidance of thinking about a trauma and then mislabeling the physical and emotional consequences of the avoidance could heighten perceived symptoms. A distinctive aspect of the model is that factors such as smoking and depression, which are often treated as confounding variables to be controlled, are mechanisms through which PTSD can adversely affect health (Schnurr and Green 2004).

Schnurr and Green’s (2004) model uses the concept of allostatic load to explain how these mechanisms could lead to disease. Allostatic load is defined as “the strain on the body produced by repeated up and downs of physiologic response, as well as the elevated activity of physiologic systems under challenge, and the changes in metabolism and wear and tear on a number of organs and tissues” (McEwen and Stellar 1993, p. 2094). Because load is defined by cumulative changes, over time and across biological systems, it explains how changes in PTSD that are too subtle to produce disease by themselves could lead to disease (Friedman and McEwen 2004; Schnurr and Green 2004; Schnurr and Jankowski 1999). Schnurr and Jankowski (1999) gave the example of hyperarousal and hyperreactivity in PTSD in combination with the physical effects of substance abuse and smoking and suggested that allostatic load might be greater in PTSD relative to other mental disorders. This hypothesis remains to be tested, but one study found that allostatic load was higher in individuals with PTSD than in traumatized controls (Glover et al. 2006).

5.3 Review of the Literature

There is abundant evidence linking PTSD with poor physical health across a range of outcomes (Friedman and Schnurr 1995; Green and Kimerling 2004; Schnurr and Jankowski 1999). In terms of self-reports, PTSD is associated with poor general health, more physical symptoms and number of chronic health conditions, and lower physical functioning (e.g., Boscarino 1997; Cohen et al. 2009a; Löwe et al. 2010; O’Toole and Catts 2008; Vasterling et al. 2008). For example, in a large national probability sample of US adults, PTSD was associated with increased odds of neurological, vascular, gastrointestinal, metabolic or autoimmune, and bone or joint conditions (Sareen et al. 2005). Most of the findings are from cross-sectional studies, but some evidence comes from longitudinal studies that have found initial PTSD to predict poorer health at a subsequent follow-up (Boyko et al. 2010; Engelhard et al. 2009; Vasterling et al. 2008). A recent meta-analysis of 62 studies, most of which were based on self-reported physical health or other nonobjective indicators, found significant effects of PTSD on health ranging from r = .17 for cardiorespiratory health to r = .48 for general physical symptoms (Pacella et al. 2013).

PTSD also is associated with poor health measured by objective indicators such as physician-diagnosed disease in both cross-sectional (e.g., Agyemang et al. 2012; Andersen et al. 2010; Nazarian et al. 2012; Seng et al. 2006) and longitudinal studies (e.g., Dirkzwager et al. 2007; Kimerling et al. 1999). The range of outcomes is striking. One cross-sectional study of a large sample of women who were receiving public healthcare in the USA found that women who had PTSD were more likely than women with another mental disorder to have syndromes such as chronic fatigue, irritable bowel, and fibromyalgia as well as disorders with more defined etiology, such as cancer and circulatory, endocrine, and respiratory disease (Seng et al. 2006). A longitudinal study found that PTSD symptoms were associated with greater incidence of physician-diagnosed arterial, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and dermatological disorders in a sample of older male veterans (Schnurr et al. 2000b), even after statistical adjustment for age, smoking, body mass index, and alcohol use.

Cardiovascular outcomes have been a particular focus in this literature. Prospective studies have shown that PTSD is associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease in older male veterans (Kubzansky et al. 2007), male Vietnam veterans (Boscarino and Chang 1999; Kang et al. 2006; Vaccarino et al. 2013), and civilian women (Kubzansky et al. 2009). Pain is another area of particular focus, spanning both self-reported and physician-diagnosed measures. Individuals with PTSD report higher levels of chronic pain that is not related to traumatic injury such as rheumatoid arthritis (e.g., Mikuls et al. 2013) and have an increased likelihood of pain syndromes such as chronic pelvic pain and fibromyalgia (e.g., Seng et al. 2006).

Evidence on the relationship between PTSD and utilization of medical services is somewhat mixed. Some studies have found that PTSD is associated only with greater use of mental health services or emergency care (e.g., Possemato et al. 2010). However, the majority of studies have found that PTSD is associated with greater use of medical care services (e.g., Gill et al. 2009; Glaesmer et al. 2011; O’Toole and Catts 2008; Schnurr et al. 2000a). Few studies have examined cost implications, but there is some evidence that PTSD is associated with higher healthcare costs (e.g., Walker et al. 2004).

All of the studies on PTSD and mortality have been conducted using military veteran samples. Some of these studies have found that PTSD is associated with excess mortality (e.g., Boscarino 2006; Kasprow and Rosenheck 2000; see Abrams et al. 2011; O’Toole et al. 2010, for exceptions). Other studies have found that PTSD is associated with mortality due only to external causes or diseases related to substance abuse (e.g., Bullman and Kang 1994; Drescher et al. 2003). A recent study found that PTSD was associated with all-cause mortality, but not after statistical adjustment for demographic, behavioral, and clinical factors (Chwastiak et al. 2010).

5.3.1 Explicit Tests of PTSD as a Mediator of the Relationship Between Traumatic Exposure and Physical Health

Evidence that PTSD mediates the effects of traumatic exposure on physical health comes from several types of analyses: (a) multiple regression analyses in which a statistically significant association between exposure and physical health is reduced or eliminated when PTSD is added to the model; (b) structural equation modeling, a more formal version of (a); and (c) comparisons involving individuals with PTSD, traumatized controls, and nontraumatized controls. Most of these studies have examined self-reported health outcomes (e.g., Campbell et al. 2008; Löwe et al. 2010; Norman et al. 2006; Schuster-Wachen et al. 2013; Tansill et al. 2012; Wolfe et al. 1994), with few exceptions (e.g., Glaesmer et al. 2011; Schnurr et al. 2000b). The effects can be substantial. For example, a study of 900 older male veterans found that PTSD mediated 90 % of the effect of combat exposure on health (Schnurr and Spiro 1999).

However, the effects also may differ across populations and outcomes. A study of Vietnam Veterans found that PTSD mediated 58 % of the effect of warzone exposure on self-reported health in men but only 35 % of the effect in women (Taft et al. 1999). A study of PTSD and self-reported health in primary care patients also found the effects of mediation to be larger in men (Norman et al. 2006). Although trauma exposure was related to digestive disease and cancer in women, PTSD did not mediate these relationships. Exposure was related to arthritis and diabetes in men, but PTSD mediated only the association between trauma and arthritis. In another study showing differential mediation across outcomes, combat exposure predicted increased incidence of physician-diagnosed arterial, pulmonary, and upper gastrointestinal disorders and other heart disorders over a 30-year interval in older veterans, yet PTSD mediated only the effect of exposure on arterial disorders (Schnurr et al. 2000b).

5.3.2 Evidence on Potential Mechanisms Through Which PTSD Affects Physical Health

To date, no study has simultaneously examined the psychological, biological, behavioral, and attentional factors Schnurr and Green (2004) hypothesized to mediate the relationship between PTSD and health. Instead, studies have focused on specific domains or individual factors.

Of all the potential psychological mediators, depression is arguably the most important because it has well-documented associations with a range of physical health problems (Ford 2004). The data on depression are generally consistent with its hypothesized role as a mediator of the relationship between PTSD and health. For example, in one study, controlling for depression significantly reduced the association between PTSD and somatic symptoms, which is consistent with the idea that depression is a mediator of the relationship (Löwe et al. 2010). In another study, depression fully mediated the relationship between PTSD and pain (Poundja et al. 2006). Depression also may mediate the relationship between PTSD and other mediators. Zen et al. (2012) found that depression mediated the relationship between PTSD and both physical inactivity and medication nonadherence.

The data on health behaviors are mixed. Some studies have found that health behaviors are partial mediators of the relationship between PTSD and health (e.g., Crawford et al. 2009; Flood et al. 2009). Other studies have failed to find that health behaviors mediate the relationship (e.g., Del Gaizo et al. 2011; Schnurr and Spiro 1999). Although it makes sense that health behaviors would at least partially mediate the relationship between PTSD and physical health, these behaviors do not appear to account for a substantial amount of the effect. Furthermore, many studies have controlled for these factors and still find that PTSD is related to poor health (e.g., Boscarino 1997; O’Toole and Catts 2008; Schnurr et al. 2000b).

In terms of biological mediators, the most substantial evidence comes from studies of risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Individuals with PTSD are more likely than individuals with depression or with no mental disorder to have hypertension (e.g., Kibler et al. 2008). A recent study found that PTSD symptoms were associated with increased risk of developing obesity in a group of normal-weight nurses who were followed over a 16-year interval (Kubzansky et al. 2013). Another recent study found that male and female veterans with PTSD were at increased risk of obesity, as well as smoking, hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia (Cohen et al. 2009b). PTSD also is associated with low-grade inflammation, an additional risk factor for cardiovascular disease (Guo et al. 2012; Pace et al. 2012; Spitzer et al. 2010).

Friedman and McEwan (2004) had suggested that PTSD would be associated with risk of metabolic syndrome, a constellation of risk factors including obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperglycemia, and hypertension. Recent studies have found this to be the case and have shown that the association between PTSD and metabolic syndrome is independent of other risk factors such as demographic characteristics, health risk behaviors, and depression (Heppner et al. 2009; Jin et al. 2009; Weiss et al. 2011).

Metabolic syndrome illustrates one of the key features of allostatic load, which is the combined effect of multiple risk factors. The studies linking PTSD with metabolic syndrome therefore provide support for the possibility that higher allostatic load is a key mechanism through which PTSD affects physical health.

5.3.3 Evidence on Whether Treating PTSD Improves Physical Health

Despite the evidence suggesting that PTSD leads to poor health, there is only limited information on the question of whether treating PTSD improves health. The best evidence comes from studies that have used measures of self-reported physical symptoms and physical functioning, but the evidence is not consistent. Recent studies have found that symptoms (Galovksi et al. 2009; Rauch et al. 2009) and functioning (Beck et al. 2009; Dunne et al. 2012; Neuner et al. 2008) improved following cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. For example, Dunne et al. (2012) found that cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD in patients with chronic whiplash disorders led to reductions in neck disability and improvements in physical functioning. In contrast, other studies have failed to find improvements in physical functioning following treatment with fluoxetine (Malik et al. 1999) or cognitive behavioral therapy (Schnurr et al. 2007a).

There has been very little research on the effects of PTSD treatment on physician-diagnosed disorder or other objective indicators of morbidity. Whether treating PTSD can improve a disorder such as coronary artery disease or diabetes thus is unknown and even uncertain given the mixed evidence from trials on the treatment of depression (e.g., Bogner et al. 2007; Writing Committee for the ENRICHD Investigators 2003). Even though PTSD may have increased the likelihood of an individual developing a given disorder, the biological mechanisms through which this has occurred may become independent of PTSD and nonreversible through the reduction of PTSD symptoms alone. Consider the case of metabolic syndrome. It is plausible that reduced hyperarousal following successful treatment could lead to reductions in hypertension. However, the majority of people with hypertension do not suffer from PTSD or any mental disorder (e.g., Hamer et al. 2010), so simply reducing the hyperarousal may not be sufficient in order to treat the hypertension. Furthermore, it is less plausible that obesity, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia would improve without behavioral changes such as better diet and exercise and compliance with medical regimens to control these factors.

5.4 Implications for Research

Schnurr and Green (2004) proposed a research agenda that included both methodological and content issues to be addressed. In terms of methodological issues, they called for studies based on large representative samples and on populations outside the USA, and with measures of PTSD and other posttraumatic reactions and not only measures of traumatic exposure. They also called for studies that were based on biological measures of morbidity. In terms of treatment issues, Schnurr and Green (2004) called for studies that provide more definitive information about which health problems are, and are not, associated with PTSD and other posttraumatic reactions and for measures of physical health to be added to studies of the biological correlates of PTSD. They also called for studies on reactions to traumatic exposure other than PTSD and for research on the effects of PTSD treatment on physical health, including system-level interventions designed to integrate mental and physical healthcare.

Although the evidence showing that traumatic exposure is associated with adverse physical health has grown substantially, there are still key gaps in all of these methodological and content issues. One is the lack of research on significant posttraumatic reactions in the absence of PTSD, especially depression. PTSD appears to have effects that are distinctive from the effects of comorbid disorders, but it would be helpful to delineate for which disorders PTSD has unique effects. Another key gap is the use of biological measures of morbidity. Much of the increase in this area has focused on cardiovascular disease, with less focus on other disease categories such as endocrine and immunological disorders. Studies of mechanism are critically needed, in particular, studies that examine allostatic load as a mechanism linking PTSD (and potentially, other disorders) to physical health. Further study of health outcomes in PTSD treatments trials is important, but specific efforts should be made to focus on populations with physician-diagnosed disorders. It would be useful to examine conditions that could respond to behavioral and psychological change, such as diabetes. It also would be useful to evaluate integrated efforts to reduce health risk behaviors in PTSD patients. A study by McFall et al. (2010), showing the benefits of integrating smoking cessation into PTSD treatment, is an excellent example of the latter and also of interventions that target systems of care.

There are important analytical issues to consider too. When studying events that are likely to cause injury or illness (such as accidents, combat, or torture), analyses need to delineate the direct effects of trauma from the indirect effects caused by PTSD or other reactions. Another analytic issue is how psychological and behavioral correlates of PTSD such as depression and smoking are handled. Statistically adjusting for these factors is appropriate if the goal is to determine whether PTSD has independent effects on health. If the goal is to examine these factors as mechanisms, methods such as hierarchical regression, path analysis, and structural equation modeling are more appropriate.

5.5 Implications for Clinical Practice

The effects of PTSD on physical health have implications for clinical practice. Patients with PTSD may be dealing with physical health burden in addition to PTSD: medical disorders, reduced physical functioning, and simply not feeling well. A holistic, patient-centered approach to care requires that mental health providers may need to address physical health problems, particularly if these problems interfere with treatment adherence or treatment response. Kilpatrick et al. (1997) emphasized the importance of psychoeducation to help patients understand how their trauma-related symptoms may be related to their physical problems and how addressing both physical and mental health problems could enhance recovery.

Many providers are familiar with addressing substance use disorders when treating trauma survivors. Providers may need to address additional health risk behaviors as well and make necessary referrals. Some providers may be reluctant to address smoking in particular out of a concern that patients who use smoking to help manage PTSD symptoms may find it difficult to stay engaged in intensive trauma-focused work if this coping strategy is taken away. However, McFall and colleagues (2010), who found that integrating smoking cessation treatment into outpatient PTSD care was effective for reducing smoking, also found that PTSD symptoms did not increase as a result of smoking cessation. Integrating medical care into a mental healthcare setting also may be helpful, particularly for patients who have significant psychiatric problems (Druss et al. 2001).

Because PTSD is associated with increased utilization of medical services (e.g., Gill et al. 2009; Glaesmer et al. 2011; Schnurr et al. 2000b), providers in medical care settings may need to increase efforts to address PTSD. Many patients with PTSD seek care only in medical settings—typically primary care, where their PTSD may go unrecognized (Liebschutz et al. 2007; Magruder and Yeager 2008; Samson et al. 1999). Providers in these settings may need to more routinely screen for PTSD and engage in strategies to help patients receive care for their PTSD symptoms. There are a variety of strategies for integrating medical and mental healthcare that have been shown to work in mental health disorders other than PTSD (Bower et al. 2006; Roy-Byrne et al. 2010), but very little research has examined these strategies in PTSD. One recent randomized clinical trial found that collaborative care using a telephone care manager was not more effective than usual care for veterans with PTSD (Schnurr et al. 2013), but further study is needed to make definitive conclusions about the optimal strategies for addressing PTSD in primary and specialty care medical settings. At a minimum, more education for patients and providers is needed (Green et al. 2011).

5.6 Implications for Society

The increased risk of poor health associated with exposure to traumatic events has important implications for society. One is that some disease may be prevented by either reducing the risk of exposure or by reducing the risk of PTSD and other significant posttraumatic disorders. The health benefits of reducing the risk of preventable exposures such as accidents and physical and sexual assault are obvious (and for reasons in addition to those specific to trauma). However, there could be important population health benefits of preventing posttraumatic symptomatology by interrupting the cascade of biological, psychological, behavioral, and attentional changes that may emerge when a traumatized individual fails to recover. There also could be important monetary benefits of prevention given that PTSD is associated with increased financial costs (Marshall et al. 2000; Marciniak et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2004).

Increased awareness of traumatic exposure and its consequences is key from a public health perspective. The greater likelihood of health risk behaviors associated with traumatic exposure, and especially with PTSD, suggests that recognition and management of posttraumatic reactions could enhance public health campaigns for problems such as smoking and obesity and the importance of engaging in preventive healthcare to improve population health. Increased awareness of the effects of traumatic exposure and PTSD on physical health is needed at a global health level as well, particularly in countries with recent or ongoing conflict or disasters and in third world countries with limited healthcare and mental healthcare infrastructure.

The relationship between traumatic exposure and poor physical health also has implications for legal and compensation systems. Should individuals with PTSD receive compensation for physical health problems? It makes sense that an individual who developed PTSD and sustained permanent knee damage as a result of a life-threatening accident at work would receive compensation for both conditions. But should the same individual receive additional compensation after developing coronary artery disease or diabetes? The scientific evidence at this point is not conclusive enough to support the burden of proof necessary to determine causality. Furthermore, there are no established scientific methods for determining whether such disease in a given individual is due to posttraumatic symptoms or other factors. This is an extremely complicated question to answer because physical disorders are typically influenced by multiple factors, including genetics, demographic characteristics, pretraumatic health, and posttraumatic factors unrelated to the trauma.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree