Children and adolescents who suffer abuse, neglect, or trauma are at increased risk for a range of mental health problems. Children who have been abused physically or sexually may exhibit posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety disorders or mood problems, and aggressive behavior. Children who are severely neglected may exhibit reactive attachment disorders (RADs). Sexual abuse may have special sequela in terms of depresssion, substance abuse, low self-concept, and dissociative states. Neglectful and depriving caregiving environments also increase children’s risk for problems in social development and attachment.

Neglect can occur in various forms or combinations of forms, including physical, educational, or emotional. Although poverty and low parental education are risk factors, abuse and neglect are observed in families from all social situations, and clinicians should be constantly alert to the possibility of abuse or neglect. In some instances, the medical system itself becomes involved in the cycle of abuse—in the case of so-called Munchausen by proxy syndrome. Children exposed to trauma within or outside the family are prone to exhibit a range of difficulties, including PTSD.

As an historical phenomenon, child abuse is not new. Abraham’s near sacrifice of his son Jacob provides an early reference to potential abuse. Indeed, infanticide was a common phenomenon for religious or economic reasons and continues to the present. Foundling hospitals were equipped to accept infants or children who otherwise would have been abandoned. Only in relatively recent times has child abuse come to be regarded as a medical condition; terms such as battered child syndrome and shaken baby syndrome came to be used as physicians appreciated the physical findings associated with abuse. Similarly, interest in the response to trauma is also relatively recent.

CHILD ABUSE

Definitions and Clinical Features

Physical abuse entails the intended injury of a child by the caretaker. For infants, this may take the form of shaking or beating, resulting in “shaken baby syndrome.” Injury may come from inappropriate or excessive punishment. The term

battered child is often used to refer to the victims of physical abuse. In sexual abuse, an adult or older child engages in inappropriate

sexual behavior with a child. Psychological abuse takes the form of repeated threats of abandonment or repeated statements to the child that he or she is unwanted, unloved, or damaged.

The term

neglect is generally used to refer to situations in which the parent or caretaker does not provide appropriate care of children. This can take the form of failure to provide sufficient food, adequate supervision, or inadequate medical care or education. Physicians and other health care providers are mandated reporters of suspected abuse and neglect. Legal definitions vary from state to state; it is important for health care providers to be aware of the mandates for reporting in their own locations. Unfortunately, the various forms of abuse and neglect frequently co-occur.

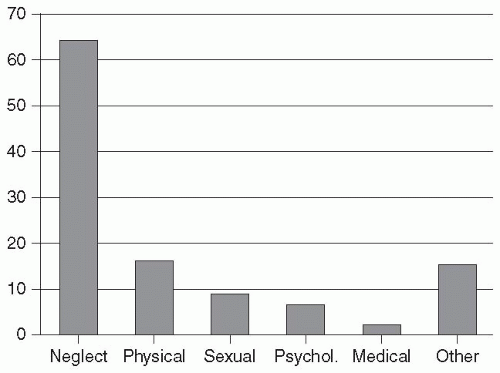

Figure 20.1 summarizes recent data on abuse types.

Physical abuse should be suspected if a child has injuries that appear to be the result of abuse or when the history provided does not correspond to the findings. A child who was has been abused may look anxious, fearful, depressed, or agitated; older children may be very reticent to reveal the abuse. Marks or bruises (e.g., to the face or head, back or buttocks) may suggest inappropriate punishment; these are often symmetrical (unlike most accidental injuries). Similarly, a belt or rope may leave a characteristic pattern. Burns (e.g., from cigarettes) may be noted. An infant or young child may exhibit multiple and spiral fractures. Severe shaking of an infant can lead to shaken baby syndrome with characteristic retinal hemorrhages. In Munchausen by proxy syndrome (discussed subsequently), there may be a history of repeated emergency department (ED) or hospital visits for treatment of unusual problems.

Child neglect may present to the physician with signs of malnutrition or with signs of lack of care of the child. Such children may be withdrawn and may be indiscriminate in their affection. These children may be more likely to exhibit poor hygiene and be physically small. Occasionally, neglect may present as failure to thrive, although neglect is present in a small minority of such cases.

Sexual abuse is often never revealed or comes to light only after a long pattern of abuse. Uncovering the abuse may be difficult. Obvious indicators are unexpected trauma or sexually transmitted diseases. A young child who is sexually abused may display inappropriate sexual knowledge or preoccupation; behavioral manifestations may include mood problems or aggression. The child may be fearful (e.g., of men if the perpetrator is himself a male). In interviewing the child with suspected child abuse, the examiner should understand that the

child may not always be consistent given understandable anxiety. False allegations of sexual abuse do occur, and in many cases, there is not sufficient evidence to substantiate the claim of sexual abuse. Very young children may have great difficulty providing a coherent verbal account of the abuse. The use of play materials can be helpful, but it is important that the interviewer not inappropriately “lead” the child. Incestuous behavior is most common between older male relatives (fathers, brothers, uncles, stepfathers) and girls. Risk factors include poverty, absent or impaired maternal presence, and substance abuse.

All states mandate reporting of possible abuse and neglect on the part of health care providers. Guidelines for evaluation of cases of physical and sexual abuse have appeared (see Selected Readings). It is important for professionals working with children to be aware of specific reporting requirements in their state. Given the high rates of psychiatric sequelae, the possibility of abuse and neglect should be considered in initial evaluations in mental health settings.

Epidemiology and Risk Factors

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that in 2006, child protective services investigated 3.6 million reports of child abuse or neglect. As noted in

Figure 20.1, neglect is the most frequent form of abuse followed by physical and sexual abuse. In 2006 the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) reported over 1500 child fatalities from abuse. The children most likely to die as a result of abuse and neglect are mostly babies of less than 1 year (44% of cases) or toddlers from 1 to 3 years of age (34% of cases). It is likely that many child fatalities are not correctly reported as such. Once a case has been reported there is increased risk for subsequent referral. It is typical for the child in protective care to have experienced at least two forms of abuse. Children who suffer from abuse or neglect may exhibit any of several potential risk factors. These include prematurity or physical or cognitive disability or children who are viewed (rightly or wrongly) as demanding, difficult, or overly active. Young age is a major risk factor. Girls are at slightly higher risk than boys.

Although rates remain concerning, it is the case that efforts at prevention and education, as well as prosecution of offenders, have had a major effect. After a peak in 1993, there has been a decline of more than 20%, particularly in the areas of sexual and physical abuse. Sexual abuse in the form of attacks by other children has unfortunately appeared to have increased. Perpetrators have often been abused themselves. Unfortunately, child abuse, spousal abuse, and substance abuse problems tend to co-occur. About 80% of parents who lose their child after investigations for abuse and neglect will have histories of substance abuse, and domestic violence is reported in more than half of cases involved with child protection services.

Course and Prognosis

Neglect and abuse have varied long-term implications for the mental health and life course of victims. Psychiatric problems of sample children who have experienced abuse or neglect have higher rates of PTSD, depression, attachment problem, dissociative symptoms, substance abuse problems, eating disorders, conduct or oppositional disorder, and borderline personality traits. In addition, other problems or issues may be present, including problems with peers and low self-esteem. Academic performance may suffer. In one study, about half the maltreated children had important problems in academic, behavior, and social relationships; fewer than 5% functioned well in all of these domains. In adulthood, these individuals are more likely to be involved in violence with partners and have problems being parents. Although most parents who are abusive have experienced maltreatment themselves, fortunately, overall, only about one in three children who are abused go on to become abusing parents. Inappropriate sexual behaviors are possible indicators of sexual abuse (

Table 20.1) but can also be associated with physical abuse, exposure to domestic violence or sexuality, and to mental illness. In the past, it was

believed that fecal soiling was an indicator of sexual abuse, but this has not been shown in recent work.

Most children who are sexually abused do not go on to become abusers, but most sexual offenders have experienced maltreatment in some form. Youth who are sexual abusers often have a history of abuse or maltreatment, and most engage in other antisocial activities. Fortunately, it appears that many youth who engage in sexual offenses do not do so as adults.

Children removed from the parents often enter foster care. The number of children in foster care has increased dramatically over the past several decades. Although many of the more than 500,000 children are able to return home, a large number of them (between 20% and 40%)

reenter the foster care system. Multiple placements are not at all uncommon, and about 5% of children in care have experienced 10 or more placements. Around 100,000 children live in group home or institutional settings. Multiple foster placement significantly increases the risk for subsequent antisocial and violent behavior.

Important moderating variables in mediating the impact of maltreatment and subsequent difficulties have been identified.

Caspi and colleagues (2002) identified a genetic risk between child maltreatment and later antisocial behavior, a functional polymorphism of the gene A (MAOA) involved in neurotransmitter metabolism. Children who had been maltreated and who had high levels of MAOA expressed were less likely to develop antisocial problems. This finding has been replicated in other studies. In subsequent work, the same group found that a functional polymorphism in the promoter region of the serotonin transporter (5-HTTLPR) gene was similarly involved in the moderation of maltreatment and life stress on depression.

Other lines of research suggest that support and subsequent positive parenting can modify the effects of child maltreatment. Studies using animal models have shown the potential mitigating effects of support during separation of the young animal from its mother. Similarly, the presence or availability of a supportive caregiver is associated with a better outcome.

MUNCHAUSEN SYNDROME BY PROXY

The term

Mü unchausen syndrome was used in the 1950s to describe adults who fabricated symptoms of illness. Named after the a renowned teller of tall tales, the term

Munchausen by proxy syndrome has now been used to describe a special pattern of child abuse in which parents

fabricate illness in a child, often putting the child at risk from various medical procedures and even surgery. It appears that cases of “nonaccidental poisoning” may have represented the first instances of this condition, which was described by Sneed and Bell in 1976 as the

dauphin of Munchausen and by

Meadow in 1977 as

Munchausen by proxy syndrome.

This condition is listed in the appendix of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV) as a condition requiring further study. It is usually defined by the combination of intentional feigned illness by a parent or caregiver on behalf of a child or someone in his or her care. That individual denies having caused the illness, and there is some psychological gain for the parent or caregiver in assuming, by proxy, the sick role.

The best approach to the definition has been the object of debate. The severity can range from mild to severe. There are other circumstances in which symptoms may be falsified (e.g., in relation to keeping a child out of school or as part of a custody dispute), and these are not typically considered forms of Munchausen syndrome by proxy.

Fortunately, the condition is apparently quite rare. In one study in the United Kingdom and Ireland, the rate was one per 200,000 in children younger than 16 years of age, with most cases reported in the first year of life. A handful of systematic case reviews suggest some commonalities among cases. In addition to the generally expected young age of the children involved, the perpetrator is usually the mother. The mean age of being reported is between 3 and 4 years, although in the British study, the median age was 20 months. Boys and girls are equally as likely to be effected.

The clinical presentation can be highly varied. Usually, the apparent illness seems to be multisystem; at different points in time, the child may appear to have different disorders. In systematic case series reviews, the most common clinical presentations were possible seizures, apnea, diarrhea, and fevers. Many other presentations are reported as well. Various means are used to produce the symptoms or findings (e.g., contamination of intravenous lines or suffocation).

In some cases, the illness is simulated (e.g, by contaminating urine samples), but no damage is done to the child. There may be a history of neglect or of some nonaccidental injury. Siblings may have been the focus of similar reports. In children who present with apnea and when there is a history of sibling death caused by apnea, Munchausen syndrome by proxy should be included in the differential diagnosis. Other warning signs include symptoms only present when one person is with the child and unexplained sibling deaths. At times, the presenting issue may be a complicated, often rare, psychiatric or medical disorder.

Often, the perpetrator, usually the mother, has a long history of involvement in the health care system. Sometimes the mother herself has had a history of extensive medical evaluations. Typically, the staff report that the mother appears to be a model parent and may develop unusual (and inappropriate) relationships with medical staff. At the same time, there may be a vague sense of uneasiness on the part of the staff. Frequently, the mother will seem to hover over the child and never leave the bedside. Interestingly, covert videotaping sometimes reveals a rather different pattern when the mother believes she is not being observed. Rather than be distressed in discussing the child’s illness, the mother may seem detached or blandly accepting. The perpetrator may fabricate other information about herself, the child, or family members. Usually, unlike the mother, the father seems largely absent. The marriage relationship may be poor. In contrast to mothers, fathers who are involved as perpetrators are often demanding and unreasonable.

Risk factors include the mother’s own experience of abuse as a child, a pathological relationship with the child, and an investment in the interaction with the medical care system. Parent perpetrators also contribute their own, sometimes extensive, psychopathology, with high rates of somatoform or factitious disorders along with substance abuse, depression, and personality disorders. The fabrication of illness is often described as “quasidelusional.” There may be an element of disassociation in their presentation as well.

Relatively less is written about the psychiatric aspects of the child who is the victim. For older children, it may be the case that the child is involved the deception. Given the number of intrusive and invasive tests and procedures, children frequently learn to tolerate them rather passively.