▪ Sleep and Sleep Disorders

BACKGROUND

There have been major advances in understanding sleep and sleep problems in both children and adults over the past several decades. This began with the advent of polysomnographic (PSG) sleep recording in the 1950s and the description of rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. Consensus on nosology and classification and the development of both sleep laboratories and clinical training programs have advanced the field. Sleep disorders medicine has now been recognized and includes a pediatric section (see Anders, 2007, for detailed discussion).

THE ORGANIZATION OF SLEEP: DEVELOPMENTAL ASPECTS

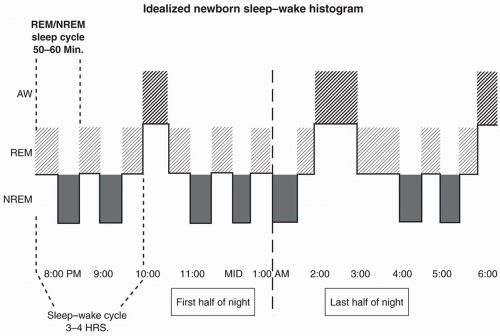

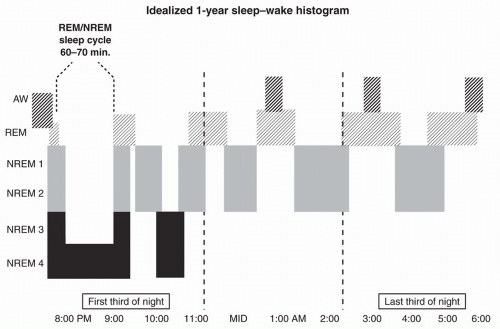

The organization of sleep-wake patterns has marked developmental aspects. Adults spend about 80% of their sleep time in NREM sleep and 20% in REM. In contrast, newborn infants spend about half of their time in REM sleep. Other differences include the duration of sleep and the length of the average sleep cycles. By adolescence, individuals archive the pattern of sleep organization seen in adults (Table 16.1). Other differences include the pattern of sleep. When adults begin to sleep, they typically start in stage 4 of NREM sleep and spend a considerable initial period in this sleep stage before the REM-NREM cycles recur, at intervals of about 90 minutes, during the night. Proportionally, most of the REM sleep occurs in the latter part of the sleep cycle in adults. Interestingly, infants have sleep patterns associated with an initial REM period and with REM and NREM sleep alternating through much of the night. The gradual reorganization of the sleep cycles begins early in life as central timing mechanisms become more active.

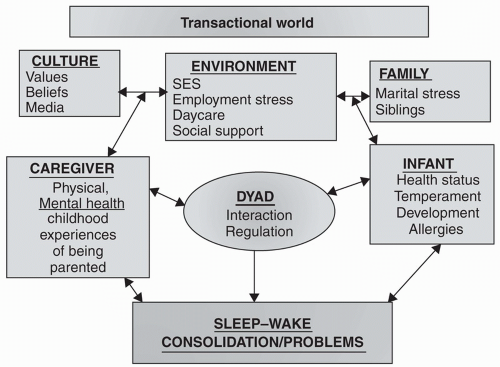

For developing infants (and for the parents), the regulation of sleep-wake cycles and the ability to sleep through the night are important tasks that provide important opportunities for interaction and set the stage for other aspects of self-regulation. Difficulties in this process thus typically require some assessment of psychosocial and parent-child issues that might be having an impact. Factors important in this regard include the physical and mental health of the caregivers, their own history of being parents and experiences of sleep, social and family support and resources, and the infant’s own temperament (see Chapter 2). The latter has

increasingly been recognized as a critical aspect of the situation. Cultural, family, and other environmental influences may be important as are other potential variables such as the physical conditions of the infant and mother. There are frequently complicated interactions between the infant’s sleep pattern and the entire family’s ability to sleep through the night. In clinical practice, all possible permutations and combinations are seen (e.g., some infants may sleep or nap at day care but not at home or an infant may be more readily put to bed by a nanny or other caretaker than the parents). Occasionally, infants sleep better for one parent or the other (a particularly complex family dynamic). Figures 16.1 and 16.2 illustrate idealized sleep-wake patterns in newborns and one year olds, respectively, and Figure 16.3 provides a schematic of the context in which sleep problems emerge.

increasingly been recognized as a critical aspect of the situation. Cultural, family, and other environmental influences may be important as are other potential variables such as the physical conditions of the infant and mother. There are frequently complicated interactions between the infant’s sleep pattern and the entire family’s ability to sleep through the night. In clinical practice, all possible permutations and combinations are seen (e.g., some infants may sleep or nap at day care but not at home or an infant may be more readily put to bed by a nanny or other caretaker than the parents). Occasionally, infants sleep better for one parent or the other (a particularly complex family dynamic). Figures 16.1 and 16.2 illustrate idealized sleep-wake patterns in newborns and one year olds, respectively, and Figure 16.3 provides a schematic of the context in which sleep problems emerge.

TABLE 16.1 SLEEP-WAKE STATE CHANGES WITH AGE | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

FIGURE 16.1. Note the regular distribution (˜50:50) between rapid eye movement (REM) and non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep throughout the sleep cycle and the initial REM sleep period at sleep onset. (From Anders, T. F. (2007). Sleep disorders. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 4th edition (p. 626). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

FIGURE 16.2. Note that the majority of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) 3 and 4 occurs during the first third of the night and that rapid eye movement (REM) periods progressively lengthen during the middle and last third of the sleep cycle. The initial REM sleep bout is brief and sometimes absent. The descent to NREM stages 3 to 4 is rapid. (From Anders, T. F. (2007). Sleep disorders. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 4th edition (p. 626). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

FIGURE 16.3. Transactional world. (From Anders, T. F. (2007). Sleep disorders. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 4th edition (p. 627). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

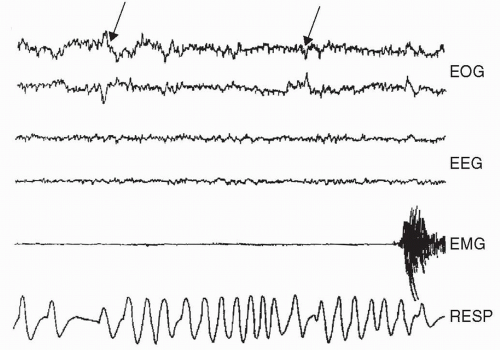

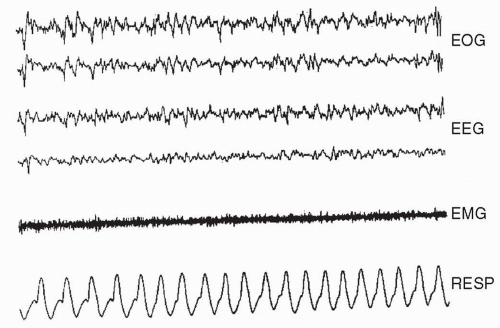

FIGURE 16.4. Polygraphic recording of rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. An epoch of REM sleep in a newborn infant characterized by a low-voltage, fast electroencephalogram; active rapid eye movements (arrows); an inhibited electromyograph; and rapid irregular respirations. (From Anders, T. F. (2007). Sleep disorders. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 4th edition (pp. 630). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. |

The typical sleep laboratory usually obtains a variety of measures during a sleep study. These include measures of peripheral muscle tone and eye movements and an electroencephalogram (EEG) as well as other measures of cardiac, respiratory, and peripheral motor activity. Typically, these measures are obtained from nighttime recordings in a sleep laboratory, although sometimes several nights of recording are required, particularly for children, given the potential for the various sensors and unfamiliar setting to disrupt usual sleep patterns. Increasingly, there is potential for both home-based and 24-hour recording approaches, which have particularly value for children. Figures 16.4 and 16.5 present the differences in records of REM and NREM sleep in newborns and one year olds.

FIGURE 16.5. Polygraphic recording of non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep. An epoch of NREM sleep characterized by high-voltage, slow waves on the electroencephalogram; an absence of rapid eye movements; a tonic electromyograph pattern; and slowed, regular respirations. (From Anders, T. F. (2007). Sleep disorders. In A. Martin & F. Volkmar (Eds.), Lewis’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Comprehensive Textbook, 4th edition (pp. 630). Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.) |

The EEG pattern during REM sleep is characterized by fast, low-voltage activity similar to that observed while the individual is awake. During REM sleep, there are bursts of eye movements and rapid, irregular breathing and heart rate patterns. Dreams are reported during REM sleep. Thus, although the individual appears to be sleeping, and is, significant central nervous system activity is noted. This is observed in infants as well, in whom it is sometimes referred to as active sleep. In contrast to the apparent activation during REM sleep, the pattern during NREM sleep is one associated with inhibition (e.g., slow and regular heart and breathing rate with EEG activity showing slower frequencies). In babies this stage is also referred to as quiet sleep.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree