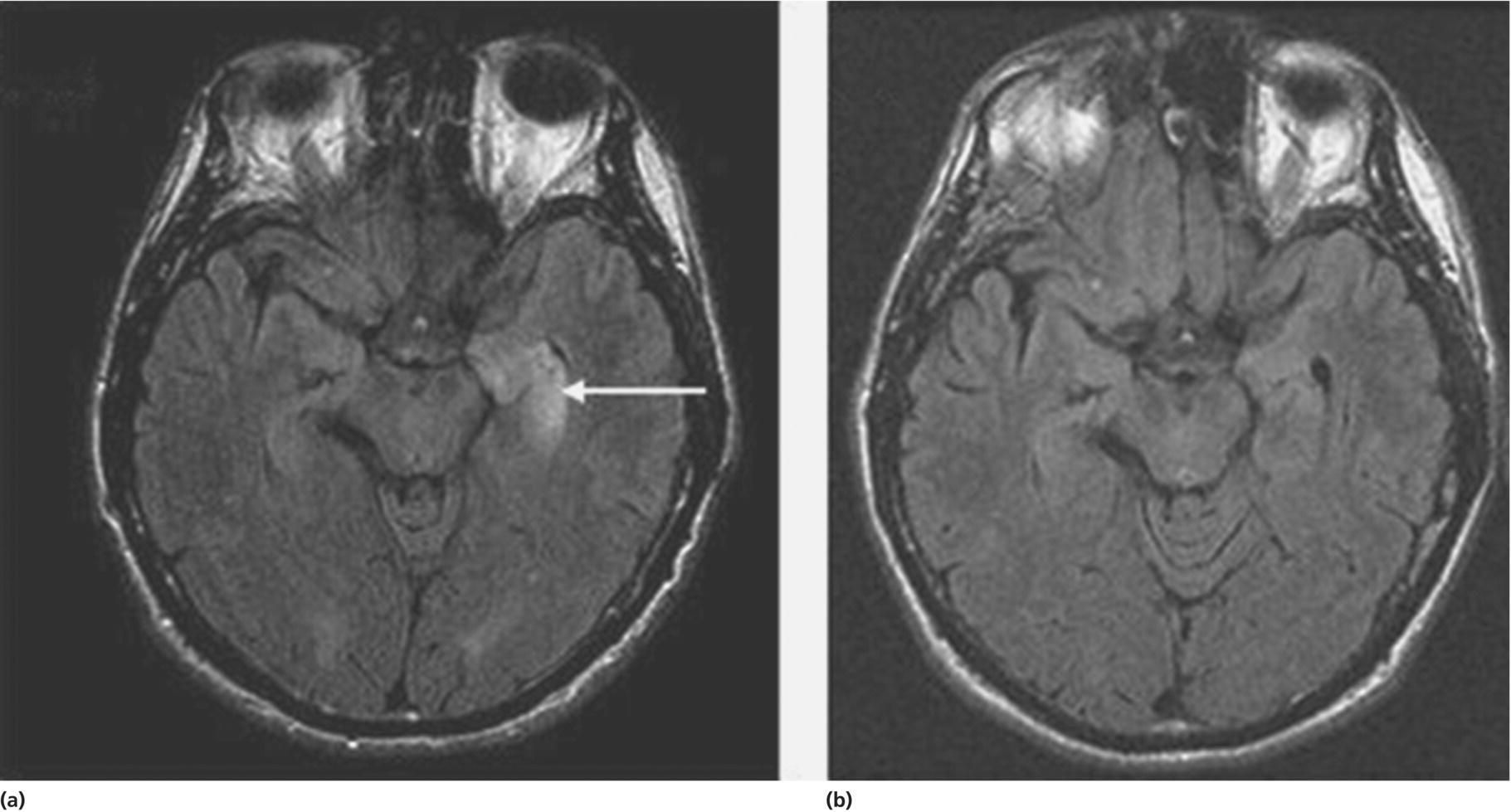

CHAPTER 10 Andrew McKeon and Sean J. Pittock Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN, USA In the evaluation of a patient with cognitive decline, clinicians should consider the possibility of an autoimmune etiology on their list of differential diagnoses. The importance of not overlooking this possibility rests in the experience that these patients have a potentially immunotherapy-responsive, reversible disorder [1]. Traditionally, neurologists have usually considered autoimmune dementias within the framework of subacute-onset delirium and limbic encephalitis only. The development and widespread availability of neural antibody marker testing has changed this perspective so that other presenting symptoms such as personality change, executive dysfunction, and psychiatric symptoms are increasingly recognized in an autoimmune context. Clues that are helpful in identifying patients with an autoimmune dementia can be summarized within a triad of (i) suspicious clinical features (a subacute onset of symptoms, a rapidly progressive course, and fluctuating symptoms) and radiological findings, (ii) the detection of CSF or serological biomarkers of autoimmunity, and (iii) a response to immunotherapy (see Table 10.1 for Key Points). This rapidly evolving field is still in its infancy, and much of the clinical data, including that related to treatment and outcomes, is documented in single cases or small retrospective cases series only. Table 10.1 Key points for autoimmune dementias. Diagnostic terms often used to describe such patients include “autoimmune encephalopathy” (which implies delirium is present) and autoimmune dementias (where there is no delirium) and immunotherapy-responsive encephalopathy (as these patients typically have improvements after treatment with corticosteroids). For brevity’s sake, we will refer to autoimmune cognitive impairment with or without encephalopathy as autoimmune dementia throughout this chapter. The nomenclature pertaining to autoimmune dementias can seem confusing. Disorders have been classified with respect to clinical phenotype (e.g., progressive encephalomyelitis with rigidity and myoclonus [aka PERM]) [2], eponym (Morvan’s syndrome) [3], pathology (e.g., nonvasculitic autoimmune meningoencephalitis (NAIM)) [4], or associated antibody (e.g., the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) antibody-associated encephalitis) [5]. In some instances, there is more than one name in the literature for a particular disorder; both Hashimoto encephalopathy [6] and steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis (SREAT) [7] refer to the same entity: a triad of cognitive problems, thyroid antibodies detected serologically, and established clinical improvement with immunotherapy. While each description contributes something to our understanding of these disorders, from the standpoint of the practicing neurologist, immunotherapy responsiveness unites these and other autoimmune dementias. The incidence and prevalence of autoimmune dementias are unknown. They are thought to be rare but are likely underrecognized. An autoimmune or inflammatory cause of cognitive decline accounts for 20% of dementia in patients under 45 years of age [8]. Autoimmune dementias typically have a subacute onset with progression more rapid than would be expected for most neurodegenerative disorders, with the exception of Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD). While limbic encephalitis (a fluctuating confusional state accompanied by one or more of seizures, agitation, memory loss, and hallucinations) is the best recognized clinical presentation [9], other symptoms of dementia including apraxia, aphasia, behavioral change, and disturbances in orientation and reasoning have been reported [10–12]. Delirium (impaired attention and consciousness) is a common, but not universal, presentation. Marked fluctuations in the clinical course and spontaneous remission suggest an autoimmune cause but can also be seen in patients with toxic and metabolic causes of dementia, in patients with psychogenic disorders, and in patients with depression. A sleep history may also be informative. Patients with Ma2 antibody encephalitis might complain of hypersomnia [13]. Conversely, patients with voltage-gated potassium channel-complex autoimmunity often complain of insomnia [14]. Patients with sleep apnea syndrome (either central or obstructive) typically have fluctuating cognitive complaints related to a lack of restorative sleep rather than an autoimmune dementia [15]. A fluctuating mental state accompanied by a sleep disorder and parkinsonism can be seen in diffuse Lewy body disease [16] (see Chapter 6). In some disorders, characteristic noncognitive features are important also. For example, in a patient with a history of visual loss and hearing loss, in addition to cognitive symptoms, Susac’s syndrome (an immunotherapy-responsive endotheliopathy) should be considered [17]. Other symptoms and signs common in Susac’s syndrome include memory loss, psychiatric symptoms, and headache. Patients with mitochondrial disorders can also present with fluctuating encephalopathies and visual and hearing impairments. This information is crucial. A history of cancer may be relevant, since an autoimmune, paraneoplastic dementia may be the herald of a recurrence of cancer. Patients with autoimmune dementia frequently have one or more coexisting autoimmune disorders, such as hypothyroidism, SLE, and rheumatoid arthritis. Likewise, a smoking history, review of systemic symptoms, and a family history of autoimmunity and cancer might be informative. Impairments in one or more categories of attention, memory, reasoning, calculation, and praxis can be documented using brief bedside evaluations such as the MMSE [18], the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA; www.mocatest.org), or the Kokmen Short Test of Mental Status [19]. More extensive neuropsychological testing, however, is often required to fully characterize the degree of cognitive impairment. This serves both to document the abnormalities present and as a pretreatment baseline. Since autoimmune neurological disorders are often multifocal [20, 21], other neurologic symptoms and signs may accompany the cognitive impairment. These may include seizures, ataxia, brainstem signs, parkinsonism, myoclonus, tremor, myelopathy, or a peripheral nervous system disorder. Both potentially reversible etiologies (Table 10.2) and neurodegenerative causes for cognitive symptoms need to be considered. Unlike autoimmune dementias, neurodegenerative disorders, with the exception of prion diseases, are usually characterized by indolent onset and slow progression over years. Neurodegenerative disorders include Alzheimer disease, frontotemporal dementia, diffuse Lewy body disease, Parkinson’s disease with dementia, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration (see Chapters 3, 5–7, and 9). Mitochondrial diseases can also lead to dementia but often have other distinguishing features, such as retinopathy, hearing loss, short stature, and/or neuropathy (www.genetest.org). Among the treatable causes to consider (Table 10.2) are some other idiopathic inflammatory disorders that are also immunotherapy responsive. Each has well-characterized clinical, radiologic, and pathologic diagnostic features and recommended treatments. Examples include multiple sclerosis, CNS vasculitis (also known as primary angiitis of the CNS), sarcoidosis, and neuro-Behçet’s disease. Table 10.2 Potentially reversible causes of cognitive impairment. The anagram CAPTIVE MINDS may aid memory. * Mitochondrial diseases can remit, although they are not currently treatable or reversible. During an MS relapse, a patient may develop subacute cognitive symptoms with delirium and impaired attention, and subsequent improvements may occur during remission [22]. Headache and rapidly progressive dementia are two characteristic presentations of CNS vasculitis [23]. The diagnosis is aided by cerebral angiography and definitively proven by demonstrating multifocal inflammation and necrosis of small arteries, primarily in the leptomeninges; some have a coexisting amyloid angiopathy. This type of biopsy might be necessary to rule out intravascular lymphoma, which can have similar angiographic findings to CNS vasculitis [24]. Although noncognitive deficits (such as cranial neuropathies) are most common in CNS sarcoidosis, some patients may present with cognitive deficits [25]. The diagnosis often proves elusive in patients without systemic disease, and brain biopsy may be required to establish the pathological hallmark of an inflammatory infiltrate with noncaseating granulomas. Behçet’s disease is characterized by uveitis, oral aphthae, and genital ulcerations. Presentations of neuro-Behçet’s disease may include a rapidly progressive subcortical dementia characterized by amnesia and a frontal dysexecutive syndrome [26]. In addition, patients can present with pyramidal tract, spinal cord, and sphincter dysfunction. Brain MRI often reveals focal or diffuse T2-weighted hyperintensities, particularly in the basal ganglia, thalamus, upper brainstem, and mesial temporal structures [26]. Rarer infiltrative, inflammatory disorders of the central nervous system, which may be steroid responsive, include Langerhans cell histiocytosis [27], crystal-storing histiocytosis [28], and lymphomatoid granulomatosis [29]. There are several components to testing when evaluating a patient with autoimmune dementia. Some testing aids with documenting objective abnormalities, which serves as a baseline before a trial of treatment is undertaken. Resolution of neuropsychological, EEG, MRI (Figure 10.3), or functional imaging abnormalities after immunotherapy serves as an objective marker supporting patient-reported improvements. Figure 10.3 FLAIR axial MRIs in a patient with LGI1 (“VGKC”) antibody and limbic encephalitis with left greater than right medial temporal lobe hyperintensities (a) that had radiologic and clinical improvements (b) after corticosteroid therapy. Source: McKeon et al. [1]. Reproduced with permission of Wolters Kluwer. Neuropsychological testing, in particular, provides a detailed assessment of deficits and can be very informative in mild cases where the abnormalities are subtle. In addition, other mitigating factors leading to cognitive complaints (such as depression) can be identified by a neuropsychologist. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of literature on the precise cognitive profile of patients with autoimmune dementia. Comprehensive cognitive testing, however, is probably best, including evaluation of memory, frontal-executive function, and processing speed [12].

Autoimmune dementias

Introduction

Clinical manifestations are diverse and often multifocal

Personal history or family history of autoimmunity or cancer might provide important diagnostic clues

Antibodies targeting nonneural antigens (e.g., thyroid, antinuclear) serve as clues for neurological autoimmunity, but do not provide a definitive diagnosis

Neural-specific autoantibodies serve as markers of neurologic autoimmunity and cancer

A trial of immunotherapy (steroids, IVIG, and/or plasma exchange) serves as a diagnostic test. Trials of multiple treatment types may be required

Autoimmune dementias are frequently relapsing and immunotherapy over years may be required

Nomenclature

Epidemiology

Clinical features

Symptoms

Past and family history

Examination findings

Differential diagnoses

Potentially reversible causes of cognitive impairment

Examples

Cancer (neoplasia)

Primary CNS lymphoma (including intravascular and meningeal presentations)

Autoimmune encephalopathies and dementias

Immunotherapy-responsive disorders of presumed autoimmune etiology

Psychiatric illness

Anxiety, depression, psychosis

Toxic

Alcohol, opiates, cocaine, amphetamines, organic solvents

Inflammatory CNS disorders (other than autoimmune)

Multiple sclerosis, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, neurosarcoidosis, neuro-Behçet’s disease

Vasculopathies

CNS vasculitis, posterior reversible leukoencephalopathy (PRES), subdural hematoma, venous thrombosis

Endocrine

Disturbances in pituitary, thyroid, parathyroid, endocrine pancreatic, or adrenal function

Metabolic

Respiratory, renal or liver failure. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Mitochondrial disorders* (e.g., MELAS)

Infection of the central nervous system

HSV, HHV-6, HIV, fungal (e.g., cryptococcus), mycobacterial, Whipple’s disease, neurosyphilis

Nutritional deficiency

Vitamin B12, vitamin E, thiamine, folic acid,

Drugs

Benzodiazepines, antidepressants, antipsychotics, antiepileptics, analgesics

Seizure disorders

Nonconvulsive status epilepticus

Neurological Testing

Defining abnormalities with objective tests: Neuropsychological testing, imaging, and EEG

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree