INTRODUCTION

Obesity is one of the most common problems in clinical practice. Defined as a body mass index (BMI) of greater than 30 kg/m2, over 33% of adult Americans are obese. An additional 35% are overweight, with BMIs between 25 and 30 kg/m2. Almost one-third of children are overweight or obese. Because obesity is at the center of chronic disease risk and psychosocial disability for millions of Americans, its prevention and treatment offer unique patient care and public health opportunities. If all Americans were to achieve a normal body weight, it has been estimated that the prevalence of diabetes would decrease by half, whereas hypertension, coronary artery disease, and various cancers would decrease by 10–20%.

Obesity is often one of the most difficult and frustrating problems in primary care for both patients and physicians. Considerable effort is expended by primary care providers and patients, often with little benefit. Weight-loss diets, for example, even in the best treatment centers, result in an average 5–10% reduction in body weight. This lack of clinical success has created a never-ending demand for new weight-loss treatments. Approximately, half of women and one-quarter of men are “dieting” at any one time, spending billions of dollars each year on diet books, diet meals, weight-loss classes, diet drugs, exercise programs, “fat farms,” and other weight-loss aids. The challenge for health care providers is to identify those patients with obesity who are most likely to benefit medically from treatment and most likely to maintain weight loss, and to provide them with sound advice, skills for long-term lifestyle change, and support. For patients not motivated to attempt a weight-loss program, health providers must continue to be respectful and empathic and focus on other health concerns. Whenever possible, providers should emphasize prevention of obesity and further weight gain and the importance of physical fitness independent of body size.

DEFINITIONS

Obesity is defined as an excess of body fat. Body fat can be measured by several methods including total body water, total body potassium, bioelectrical impedance, and dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry. In clinical practice, however, obesity is best defined by the BMI—body weight divided by height squared (kilograms per square meter). The BMI correlates closely with measures of body fat and with obesity-related disease outcomes. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), an individual with a BMI lesser than 18.5 kg/m2 is classified as underweight, 18.5–24.9 kg/m2 as normal, 25.0–29.9 kg/m2 as overweight, and greater than or equal to 30.0 kg/m2 as obese. Obesity is further classified as class I (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2), class II (BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2), and class III or extreme obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2). The term “morbid obesity” is best avoided for those with class III obesity since obesity-related morbidity can occur at any obesity level.

PREVALENCE OF OBESITY

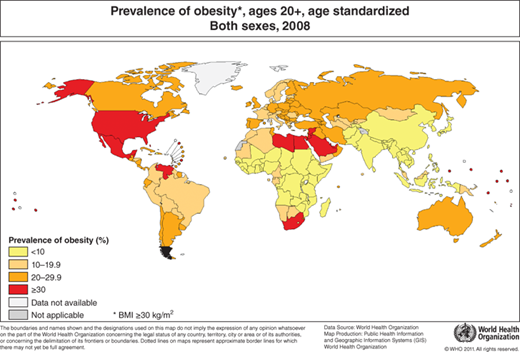

Globally the prevalence of obesity doubled between 1980 and 2008. According to the World Health Organization, in 2008 10% of men and 14% of women in the world were overweight, compared with 5% for men and 8% for women in 1980. The prevalence of overweight and obesity were highest in the Americas and lowest in South East Asia. (though there is emerging evidence that the BMI cut-off point in Asian populations for overweight should be 22 kg/m2).

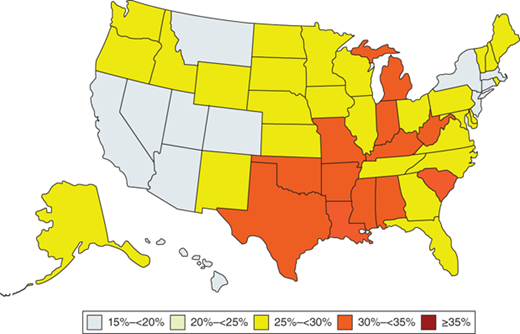

While overall the prevalence of obesity in the United States has increased dramatically over the last four decades in both adults and children differences between demographic groups are common. In women aged 40–59 years, for example, obesity is substantially more common in black and Hispanic women (52% and 47%, respectively) than in white women (36%). Similarly in teens, blacks and Hispanics (28% and 17.5%, respectively) have higher rates of obesity than whites (14.5%). Other subpopulations have dramatically increased rates of overweight and obesity. Eighty three percent of patients with mental illness, for example, are obese or overweight. Geographic differences in prevalence are also prominent in the United States. Obesity is more common in the southeastern United States than in other regions.

HEALTH CONSEQUENCES OF OBESITY

The relationship between body weight and mortality is curvilinear, similar to other cardiovascular risk factors. Most studies have demonstrated a J-shaped relationship, suggesting that the thinnest portion of the population also has an excess mortality. This is primarily due to the higher rate of cigarette smoking in the thinnest group except in the elderly, in whom malnutrition and being underweight is predictive of excess mortality independent of cigarette use. Recent analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Study (NHANES) has suggested that overweight individuals may not have as much excess mortality as previously described and that the impact of obesity on mortality overall may be decreasing over time. Racial and ethnic factors may also impact the relationship of weight and mortality. In African Americans, the weight associated with the point of lowest mortality is greater than in whites, whereas in Asian Americans it is lower.

The increase in total mortality related to obesity results predominantly from coronary heart disease (CHD). Although it is not fully established that obesity is an “independent” risk factor for CHD, obesity is clearly an important risk factor for the development of many other CHD risk factors. Obese individuals aged 20–44 years, for example, have a three- to four-fold greater risk for type II diabetes, a five- to six-fold greater risk for hypertension, and twice the risk for hypercholesterolemia. The obese also have an increased risk for some cancers, including those of the colon, ovary, and breast.

As a result of these conditions, mortality from all causes for persons with class I obesity (BMI 30–34.9 kg/m2) is 20% greater than for those with a normal BMI. Individuals with class II obesity, BMI 35–39.9 kg/m2, have an 80% increase in mortality from all causes. Mortality for extreme obesity, although less well studied, is estimated to be at least double that of normal weight individuals.

Obesity is also associated with a variety of other medical disorders, including degenerative joint disease of weightbearing joints, diseases of the digestive tract (gallbladder disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease), thromboembolic disorders, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure (both systolic and diastolic), respiratory impairment including sleep apnea, and skin disorders. Obese patients also have a greater incidence of surgical and obstetric complications, are more prone to accidents, and are at increased risk of social discrimination. Several studies have also shown a rate of depression higher in the obese than in normal weight subjects and a higher rate of binge eating disorder.

In addition to the total amount of excess body fat, the location of the excess body fat (regional fat distribution) is a major determinant of the degree of excess morbidity and mortality due to obesity. Increased upper body fat (abdomen and flank) is independently associated with increased cardiovascular and total mortality. Body fat distribution can be assessed by a number of techniques. Measurements of skin folds (subscapular and triceps) reflect subcutaneous fat. Measurement of circumferences (waist and hip) reflect both abdominal and visceral fat. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans measure subcutaneous and visceral fat. Clinically, measurement of the waist and hip circumference is most useful, especially in individuals with BMI 25–35 kg/m2. A circumference in men greater than 102 cm (>40 in.) and in women greater than 88 cm (>35 in.) can be used to identify individuals at increased risk of developing obesity-related health problems.

ETIOLOGY OF OBESITY

Numerous lines of evidence, including both epidemiologic studies of adoptees and twins and animal studies, suggest strong genetic influences on the development of obesity. In a study of 800 Danish adoptees, for example, there was no relationship between the body weight of adoptees and their adopting parents but a close correlation with the body weights of their biological parents. In a study of approximately 4000 twins, a much closer correlation between body weights was found in monozygotic than in dizygotic twins. In this study, genetic factors accounted for approximately two-thirds of the variation in weights. Studies of twins reared apart and the response of twins to overfeeding showed similar results. Studies of regional fat distribution in twins have also shown a significant (but not complete) genetic influence.

Genetic studies have confirmed a clear relationship between genetics and obesity in both animals and humans. In humans, at least 24 genetic disorders, such as the Prader–Willi syndrome, are associated with obesity. Studies suggest that genetic influences may impact both energy intake (control of appetite and eating behavior) and energy expenditure.

Differences in the resting metabolic expenditure (RME), for example, could easily result in considerable differences in body weight as RME accounts for approximately 60–75% of total energy expenditure. The RME can vary by as much as 20% between individuals of the same age, sex, and body build; such differences could account for approximately 400 kcal of energy expenditure per day. Recent evidence suggests that the metabolic rate is similar in family members, and, as expected, individuals with lower metabolic rates are more likely to gain weight. Differences in the thermic effect of food, the amount of energy expended following a meal, may also contribute to obesity. Although some investigators have shown a decreased thermic effect of food in the obese, others have not.

Environmental factors are also clearly important in the development of obesity. The “built environment” refers to the impacts of urban sprawl, traffic congestion, and the associated sedentary lifestyle of the population as people spend more time in cars and in gridlock driving to work or shopping. The US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimates that urban sprawl due to lack of adequate land use planning is associated with increases in obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes (see Chapter 9). Decreased physical activity and food choices that result in increased energy intake also clearly contribute to the development of obesity. Medical illness can also result in obesity, but such instances account for less than 1% of the cases. Hypothyroidism and Cushing syndrome are the most common. Diseases of the hypothalamus can also result in obesity, but these are rare. Major depression, which more typically results in weight loss, can also present with weight gain. Consideration of these causes is particularly important when evaluating unexplained, recent weight gain. Numerous medications can also result in weight gain including antipsychotics such as clozapine, olanzapine, and risperidone, antidepressants such as amitriptyline and cyproheptadine, anticonvulsants such as valproate, carbamazepine, and gabapentin, and diabetic medications such as insulin and thiazolidinediones. Of note, each of these categories of medications includes drugs that do not cause weight gain. Weight gain is also common following smoking cessation. On average, patients gain 4–5 kg within 6 months of quitting smoking but some patients may gain much more.

PATIENT SELECTION FOR WEIGHT LOSS

The BMI should be measured and recorded at each clinical encounter. As with other clinical abnormalities, patients should be nonjudgmentally informed of their BMI and how it conforms to definitions of overweight and obesity. Patients who are told that they are overweight or obese by their clinician are more likely to classify weight as a health concern and have greater desire and more attempts to lose weight.

Weight loss is indicated to assist in the management of obesity-related conditions, particularly hypertension, diabetes mellitus (type II) and prediabetes, hyperlipidemia, and metabolic syndrome in any patient who is obese (BMI >30 kg/m2). Many patients with BMI 25–30 kg/m2 who have one of these conditions or significant psychosocial disability also often benefit from weight reduction.

Weight loss to prevent complications of obesity in patients without current medical, metabolic, or behavioral consequences of obesity is more controversial. In young and middle-aged individuals, particularly those with a family history of obesity-related disorders, treatment should be based on the degree of obesity and body fat distribution. Such individuals with upper body obesity (increased waist circumference) should be considered for treatment; those individuals with lower body obesity and no significant consequences of obesity can be reassured and monitored. Many such patients, however, desire weight loss for psychological, social, and cosmetic reasons. A careful discussion of the risks and benefits of weight loss in such instances helps patients make informed decisions about various weight-loss strategies.

A medical or psychosocial indication for weight loss is necessary but not sufficient to begin treatment. Treatment must be designed in the context of the patient’s readiness to change. The Transtheoretical Model of Change, also commonly known as the Stages of Change Model, is a useful framework for helping patients to modify their behavior. Developed and applied initially in smoking cessation, the model has also been used to modify eating and exercise behavior. It defines behavior change as a process of identifiable stages including precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, maintenance, and relapse. By understanding the patient’s stage of readiness to change, the clinician can work specifically with each patient to move him or her to the next stage (see Chapter 19).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree