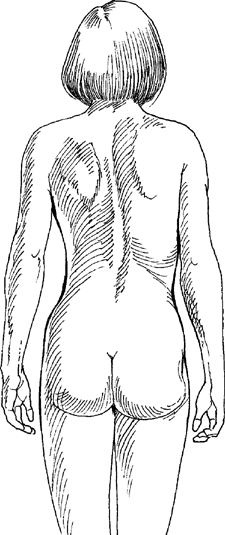

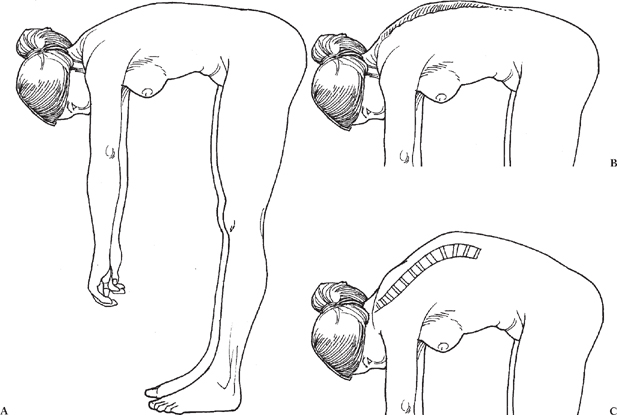

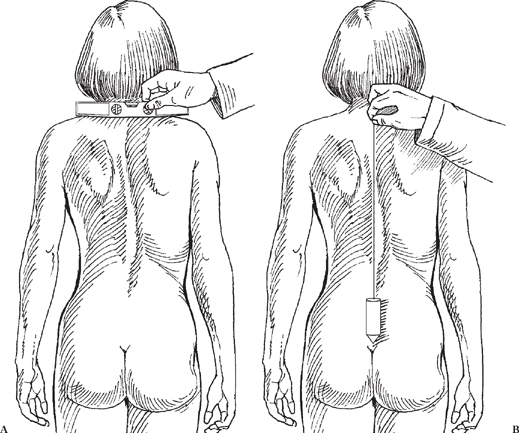

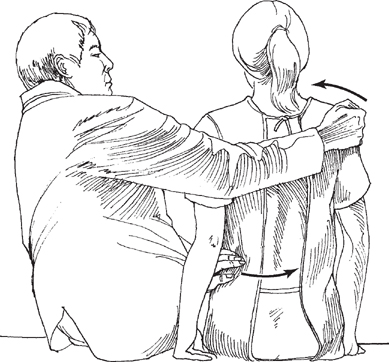

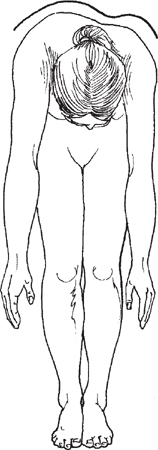

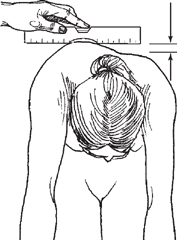

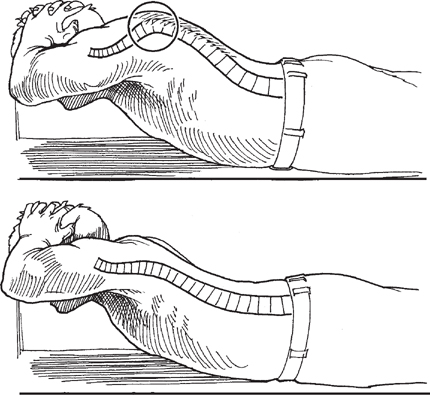

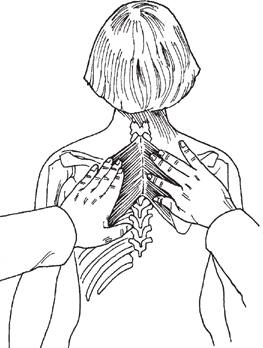

Chapter 3 CONTENTS Examination of the thoracic spine differs from that of the cervical and lumbar sections. Thoracic nerve roots, with the exception of T1, do not innervate the musculature of the extremities. Thoracic nerve root localization and testing therefore occur through palpation, movement, and sensory examination. The examination begins as the patient enters the room. First notice if the patient is distressed. Is the patient leaning to one side, and is the patient able to walk? If so, is the person’s gait normal? As in the cervical examination, ask the patient to disrobe, and stay in the room to observe. Note if the patient is limited in any motion, and note the extent of any pain elicited. Once the patient is undressed, look for signs of trauma, blisters, scars, discoloration, redness, contusions, lumps, bumps, hairy patches, café au lait spots, fat pads, and other marks. Next, instruct the patient to stand with normal posture. Look at the spine from the side, and assess the thoracic curvature with the normal kyphosis (Fig. 3-1). If possible, instruct the patient to bend over and flex the spine, and look for a lateral curvature, or scoliosis (Fig. 3-2). If a lateral curvature is seen, ask the patient to sit, and reexamine to check if the lateral curvature persists. Figure 3-1 Posterior view of a patient with scoliosis. Notice the right scapular elevation and spinal curvature. The patient should be told to fully extend the knees and have the arms at the sides when being visually inspected. To perform an appropriate deformity evaluation, certain measures must be used; additionally, you must determine specific historical details relating to skeletal maturity and growth (especially in adolescent idiopathic scoliosis). Any deformity is at the highest risk of progression during maximum skeletal growth velocity. This occurs 6 months prior to and 6 months after menarche in a female. In boys, it is more difficult to correlate with an event. Thus, maturity is judged indirectly by pubic hair development and growth measures. Figure 3-2 (A) Estimation of sagittal curvature and kyphotic angulation grossly by having the patient bend forward and evaluating the thoracic kyphosis. (B) Thoracic kyphosis evaluation. (C) Thoracic kyphosis with apex approximately at T8. Besides inspecting for a curvature, shoulder height should be measured (Fig. 3-3). The plumb line is measured by hanging a weight on a string from the C7 spinous process. This line should pass through the center of the gluteal fold. Deviation to the right or left is measured in centimeters and recorded as coronal decompensation in either direction. The flexibility of any scoliotic deformity should be evaluated by side bending, with inspection of the deformity’s correctability (Fig. 3-4), as well as by applying traction (or unweighting to the curve) (Fig. 3-5). Figure 3-3 (A) Evaluation of shoulder heights. The level should be placed across the shoulder at the top of the scapula. Notice the right shoulder elevation in this patient. (B) Plumb line dropped from the C7 (vertebra prominens) should fall in the gluteal cleft for perfect spinal balance. Measures should be made on how many centimeters to the right or left the plumb line falls from the C7 vertebrae as a measure of coronal imbalance. Figure 3-5 Measurement of curve correctability unweighting the spine by lifting the patient from under the axilla. This is the equivalent of a traction maneuver to see how much correction is obtained with the traction. The Adam’s forward-bending test (Fig. 3-6) helps to determine if a thoracic or lumbar prominence exists, implying spinal rotation (scoliosis). The prominence is measured by a scoliometer (Fig. 3-7), giving an angular reading, or by measuring the height of the prominence directly and recorded in centimeters (Fig. 3-8). Figure 3-6 Adam’s forwardbending maneuver. The spinal rib hump can be clearly estimated by viewing the patient’s back from superior-inferior and comparing the elevated side (convexity) to the lower side. It is usually reported as number of centimeters of elevation. Figure 3-7 Using a scoliometer to measure the angle of prominence. This is reported in degrees comparing the elevated side to the nonelevated side. Figure 3-8 Using a level to estimate the centimeters of rib hump elevation. Viewing the forward bend from the side helps with thoracic kyphosis evaluation (Fig. 3-2). The examiner should look for rounding of the thoracic spine implying kyphosis. Correctability or flexibility of thoracic kyphosis is tested by having the patient extend the thoracic spine (Fig. 3-9). All of these tests are intended to document and evaluate thoracic scoliosis and kyphosis. Figure 3-9 Evaluating flexibility of thoracic kyphosis by patient extension. This can help delineate between postural kyphosis and fixed structural kyphosis. Begin by feeling the general surface temperature over the thoracic spine using the backs of the hands. Compare one side with the other. Note any areas of sweating or pain, and use caution when palpating these areas. Spinous Processes To palpate the spinous processes of the thoracic spine, begin by finding C7 or T1 (Fig. 3-10). These are the most prominent of the spinous processes and can easily be found by running a finger down the midline of the flexed neck. Place the thumb of each hand on the spinous processes and begin to palpate, in a caudal direction, until you have traveled past the ribs (Fig. 3-11). Note any misalignments, curvature, lumps, pain, tenderness, and/or swelling.

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE THORACIC SPINE

Chapter 3

PHYSICAL EXAMINATION OF THE THORACIC SPINE

VISUAL EXAMINATION

DEFORMITY EVALUATION

PALPATION

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree