CAPTA was amended in 1988 (Public Law 100-294), directing the Secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to establish a national data collection and analysis program that would make available detailed state-by-state child abuse and neglect information. HHS established the National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCANDS) as a voluntary national reporting system, which produces annual reports concerning child maltreatment. As documented in Child Maltreatment 2008 (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2010), there were approximately 3.3 million referrals involving the alleged maltreatment of approximately 6.0 million children received by child protective services agencies. Nearly 63% of the referrals were screened in for investigation by child protective service agencies, and of those, approximately 24% of the investigations determined at least one child to be a victim of abuse or neglect—approximately 772,000 children. Most were victims of neglect (549,000), but there were also substantial numbers of victims of physical abuse (124,000), sexual abuse (70,000), and psychological maltreatment (56,000). Many children suffered multiple types of maltreatment. In 2008, there were 1,740 deaths of children known to be related to abuse or neglect.

As alarming as these statistics may be, they represent only the tip of the iceberg. For example, using a very conservative lifetime prevalence of 5% for serious or damaging sexual abuse, I calculate that there would be more than 200,000 cases per year.3 In the clinical arena, adult patients rarely report that they disclosed their childhood sexual abuse or that it was discovered around the time that it occurred. This observation is supported by a study analyzed by Finkelhor and his colleagues (1990) of 2,626 American men and women, in which many of those who were victims of sexual abuse never previously disclosed their experiences.

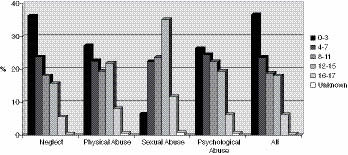

Despite the underestimating of actual prevalence, the NCANDS data elucidate the nature of child maltreatment and expose some commonly held fallacies concerning child abuse and maltreatment (Figure 1.2). For example, it’s assumed that victims of abuse and neglect—particularly sexual abuse—are older rather than younger children. In fact, the highest rates of maltreatment in 2008 were in the youngest age group (ages 0–3) and decreased with age. Even with sexual abuse, nearly 30% of victims were under age 8, and 53% were under age 12.

Most child maltreatment occurs within the home. Approximately 80% of perpetrators were parents; 6.5% were other relatives, and another 4.4% were unmarried partners of parents. Of the parents who were perpetrators, more than 90% were biological parents; the others were stepparents or adoptive parents. Mothers and fathers were roughly equally likely to be perpetrators of child maltreatment, although male parents or relatives were more likely to be perpetrators of sexual abuse as compared to female family members. All racial and ethic groups were represented as both victims and perpetrators, with approximately half being white and one-fifth African-American and another one-fifth Hispanic.

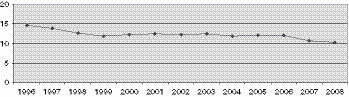

Amid all the distressing statistics concerning child maltreatment in America, there may be some reasons to feel optimistic about the future. Despite the high numbers of traumatized children, the actual annual incidence of child maltreatment appears to be decreasing. In the 12 years up to 2008, NCANDS data show that the rate of child victimization may have fallen by nearly one-third (Figure 1.3).

Have the public health efforts of government, professionals, and advocacy groups substantially changed the willingness of American society to acknowledge and intervene to prevent the maltreatment of children? If so, it is a remarkable achievement.

CHILDHOOD TRAUMA IN PSYCHIATRIC PATIENTS

Histories of childhood abuse and the symptoms of complex PTSD are extremely common among psychiatric patients. For example, our 1990 study examined nearly 100 women consecutively admitted to McLean Hospital concerning psychiatric symptoms and childhood experiences (Chu & Dill, 1990). The responses were analyzed for reports of childhood abuse and any correlations with adult symptomatology. Using a questionnaire originally developed in another study (Bryer, Nelson, Miller, & Krol, 1987), physical abuse was defined as being “hit really hard, burned, stabbed, or knocked down,” and sexual abuse was defined as “pressured against your will into forced contact with the sexual parts of your body or his/her body.” A full two-thirds of the group reported significant physical or sexual abuse in childhood. Half of the entire group reported physical abuse, and more than one-third of the group reported sexual abuse. Although these rates are high, the prevalence of sexual abuse does not differ markedly from general population statistics. What differentiates the traumatic experiences of our patients from those of nonpatients? There are many factors, including psychiatric patients being much more frequently the victims of multiple kinds of abuse, long-standing abuse, and intrafamilial abuse. The rates of abuse in our studies have been validated by almost identical results in similar studies of both inpatients (Bryer et al., 1987; Chu, Frey, Ganzel, & Matthews, 1999; Saxe et al., 1993) and outpatients (Surrey, Michaels, Levin, & Swett, 1990).

In psychiatric patients who report physical and sexual abuse, long-standing abuse beginning early in childhood is common. In one of our studies, approximately 80% of such patients reported their physical and sexual abuse as very frequent, e.g., “continuous,” “every week,” “more times than I can count” (Kirby, Chu, & Dill, 1993). Patients with chronic abuse had strikingly higher dissociative symptoms in adulthood. These patients also had disturbingly early ages of onset of their physical and sexual abuse. Nearly 60% reported that the abuse first occurred prior to age 5, and over 70% reported it occurred prior to age 11. Early age of onset was also correlated with high levels of adult symptomatology. Other studies have demonstrated that both early age of onset and chronic sexual abuse are associated with greater dissociative amnesia (Briere & Conte, 1993; Herman & Schatzhow, 1987).

To a greater extent than in general population samples, psychiatric patients are more likely to be abused within the family. Although the psychological damage inflicted by persons outside the home should not be minimized, intrafamilial abuse may be particularly damaging. In Russell’s study (1986) of women in the general population, approximately half of all sexual abuse victims were molested within the family. In contrast, in our studies of psychiatric patients (Chu & Dill, 1990; Kirby et al., 1993), the rate of intrafamilial sexual abuse in patients was much higher, with the vast majority (77%) naming family members as perpetrators. This difference in the rate of intrafamilial abuse between the general population and psychiatric populations strongly suggests that many of the psychiatric patients experienced psychological harm because their abuse was incestuous. In fact, when using dissociative symptoms as indications of psychological harm, we found that in psychiatric patients, intrafamilial abuse was correlated with more adult dissociation, whereas extrafamilial abuse was not as clearly harmful (Chu & Dill, 1990).

The damaging effect of intrafamilial abuse does not imply that abuse that occurs outside of the home is benign. Severe extrafamilial abuse may have profound deleterious effects on a child’s development. Even more alarming, the signs of abuse in a child may be far from obvious. In several instances of patients admitted to the hospital for psychiatric care, we have found evidence of serious childhood abuse that was never suspected by caring families. In fact, in a prospective study of young children, psychiatrist Frank W. Putnam, MD, found a significant number of children who had suffered abuse but who were completely asymptomatic (personal communication). Severe abuse is sometimes accompanied by numbing and dissociation, which makes it difficult for children to report abuse. Furthermore, sexual abuse in particular is often accompanied by such a sense of shame that children may be reluctant to reveal what happened. We have seen several families who have guiltily berated themselves for having missed ongoing abuse outside of the home, when the only effects at the time were the child being quieter and preoccupied, or more labile and oppositional, which are hardly unusual behaviors in children. However, our sense is that even when abuse is not known to families, a warm, caring, and nurturing family environment is enormously reparative. The innate resiliency of most children may lead to substantial spontaneous healing from brief traumatic experiences if given the necessary supportive environment.

PROGRESS IN TREATING TRAUMA

Extraordinary advances have been made recently in the study of trauma, particularly including the traumatization of children. Enormous progress has been made in understanding the prevalence of child maltreatment and its aftereffects, including posttraumatic and dissociative responses. Clinical programs, research, and teaching efforts about posttraumatic and dissociative disorders have grown and flourished since the 1980s, as both professionals and the public began to understand the psychological and physiological effects of trauma. The International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) and the International Society for the Study of Trauma and Dissociation (ISSTD) were founded in the mid-1980s and helped organize efforts to study trauma and treatment of traumatic sequelae. These organizations and the clinicians involved in the treatment and study of survivors of trauma now constitute a large and vibrant worldwide community of professionals who share a commitment to helping victims of trauma.

The trauma field has progressed remarkably in integrating diverse theories and techniques into the treatment of posttraumatic and dissociative disorders. Clinicians treating early trauma now consider its disruptive effect on attachment styles and personality development as they conduct therapy. The perspectives of self-psychology on the narcissistic damage imposed by early abuse have helped clinicians to understand the overlap of trauma-based disorders with borderline, narcissistic, and avoidant personality disorders. The trauma field has made substantial progress in addressing issues of comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, iatrogenesis, factitious and malingered presentations, somatoform symptoms, and alexithymia that affect the clinical presentations of trauma survivors. The trauma field has also responded to critics with a flood of research on traumatic and recovered memories.

Overall, treatments for posttraumatic and dissociative disorders have become more integrated with traditional therapies. The understanding of the usefulness of hypnosis in trauma has been refined, and modifications of cognitive techniques for use in treating trauma have been developed. Treatment techniques for PTSD and dissociation have proliferated, with the application of new techniques such as eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR; F. Shapiro, 2001), dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT; Linehan, 1993), and sensorimotor therapy (Ogden, Minton, & Pain, 2006). Improved pharmacologic treatments for PTSD are available, and the trauma field has benefited from revolutionary advances in understanding the neurobiology and neurophysiology of PTSD and traumatic memories.

The Evolution of a Treatment Model

The First Generation: The Early Years—Up to the Mid-1980s

In the early 1980s, a growing number of clinicians began to understand that a significant number of their patients were suffering the aftereffects of childhood trauma. Bewildering and treatment-resistant symptoms were recognized as posttraumatic and dissociative responses to overwhelming and shattering childhood experiences. Although the shift in understanding patients’ difficulties offered additional hope for successful treatment, many patients presented difficult treatment challenges, and there were few resources concerning how to treat these patients. Recognizing the role of past trauma in patients with posttraumatic or dissociative disorders, the early treatment models emphasized the importance of abreaction of the traumatic experiences as critical in the early treatment phases. This model was consistent with the reported successful treatment of adults with combat-related PTSD with acute PTSD (Kubie, 1943; Zabriskie & Brush, 1941; reported in Horowitz, 1986).4 In addition, this model was an extension of the psychoanalytic principles of venting powerful unconscious affects as a way of providing symptomatic relief. It was believed that aggressive abreaction would lead to the working through of traumatic experiences and, in the case of dissociative disorders, the reintegration of split-off parts of the self. In many cases, patients did benefit from such treatment, but others did less well.

The Second Generation: Growth—The Late 1980s to the Early 1990s

During the period of growth in the recognition of trauma and dissociation, an increasing number of clinicians became knowledgeable and skilled in the treatment of patients with trauma-related disorders. Specialty programs were opened throughout the United States and Canada, many of which became centers for the study of trauma and dissociation as well as the treatment of traumatized patients. Local, state, provincial, national, and international component groups of the ISTSS and ISSTD were formed, and teaching and information about trauma treatment became widespread and increasingly available to clinicians.

Although many traumatized patients with PTSD and dissociative disorders benefited from treatment that emphasized abreaction, others either failed to improve or even became more symptomatic. It became clear that some persons who had suffered extended traumatization in childhood not only developed posttraumatic and dissociative disorders but also had major deficits in ego functioning. The chaos and abuse of their early years interfered with learning vital skills, such as the development of basic trust and relational capacity, affect tolerance, impulse control, the ability to tolerate aloneness and to self-soothe, and a positive self-image and sense of self-efficacy. Thus, when faced with the overwhelming dysphoria involved in remembering and reexperiencing childhood trauma, many patients fled into dysfunctional isolation and sometimes compulsive behaviors, such as self-mutilation, risk-taking, substance abuse, eating disorders, and somatization. Moreover, once the dissociative barriers to traumatic memories were breached, patients became yet more overwhelmed as they were flooded by their past experiences.

The second generation of treatment models focused on the development of a phase-oriented approach, in which there was an initial phase of ego-supportive therapy to improve basic coping skills, stabilize symptoms, maintain safety, and develop affect tolerance, impulse control, stable functioning, and improved relational ability before embarking on abreaction of trauma. These tasks often proved difficult and lengthy, and they were sometimes frustrating to both patients and clinicians who wished for a more rapid and definitive resolution of trauma-related symptomatology. Abreaction remained an important component of treatment, but only when patients had achieved an adequate level of stability and were able to tolerate and contain the memories and reexperiencing of traumatic events.

The promulgation of phase-oriented treatment models for the effects of childhood abuse began in the late 1980s at some national, regional, and local conferences. However, little appeared in the scientific literature until the early 1990s (e.g., Chu, 1992c; Herman, 1992b), and acceptance of phase-oriented treatment as a standard of treatment for complex posttraumatic and dissociative disorders was gradual. Given the considerable task of reorienting, reeducating, and retraining a large number of professionals in the clinical community, phase-oriented treatment began to become part of the standard of care for traumatized patients only by the late 1990s.

The Third Generation: Conflict and Maturation—

The Mid-1990s to the Present

The False Memory Syndrome Foundation (FMSF) was founded in 1992 and began to promulgate highly publicized challenges concerning amnesia for childhood abuse, the validity of dissociative disorders, clinical research findings concerning childhood trauma, and the practices of clinicians treating victims of abuse. Acrimony and polarization ensued in the wake of FMSF attacks, with the proponents of various points of view taking extreme positions, for example, that traumatic memories (especially “recovered” memories) were either all true or all false. In fact, there was a kernel of truth to all of the points of view. In using new techniques to treat trauma and dissociation, some suggestive techniques may have been used by some therapists that allowed inaccurate reports of trauma memories. However, there was no evidence that the vast majority of trauma therapists had agendas to persuade unsuspecting patients that they were abused by their parents, and actual proof of outright implantation of memories in therapy remained extremely elusive. In fact, studies were able to lend support to the validity of recovered memories in a substantial number of patients, including those with dissociative disorders (Chu et al., 1999; Coons, 1994; Dalenberg, 1996; Kluft, 1987c). Social contagion and contamination concerning abuse memories may well have played a role in the production of poorly corroborated memories, particularly concerning memories of so-called satanic ritual abuse. However, there was no evidence that could obviate the clearly damaging effects of childhood abuse, including some experiences recalled following a period of amnesia for the events. FMSF proponents criticized the scientific methodology of studies that supported the existence of dissociation and amnesia, using arguments that clearly distorted the preponderance of evidence. In fact, dozens of studies demonstrated the correlation of dissociation with trauma and that amnesia for childhood abuse was found in virtually every study of amnesia in traumatized patients (Brown, Scheflin, & Whitfield, 1999).

In what Courtois (1999) has called the third generation of trauma treatment, clinicians have begun to acknowledge the vagaries of memory and the importance of restraint in clinical practices (e.g., recognizing that patients who have high innate dissociative capacities and who develop trauma-related disorders may also be highly hypnotizable and possibly prone to suggestion). Clinicians need to inquire directly about histories of trauma, and posttraumatic and dissociative, including possible amnesia for past events; without direct inquiry, patients who have been victimized routinely fail to volunteer such information because of ongoing shame and secrecy and the need to distance themselves from and disavow such experiences. Yet, such inquiries must be made in a way that is neutral and balanced and minimizes the possibility of suggestion. The third-generation models include more sophisticated evaluations of reports of abuse, better differential diagnosis, and treatment focused on patients’ complex and multifaceted symptoms and disabilities.

THE THERAPEUTIC CHALLENGE

The extent of childhood abuse in our society is not simply a health issue. It is also a moral and political issue. Denial and lack of awareness tacitly sanctions the abuse of a substantial number of children in our society. From prevalence study research, mandated child abuse reporting, and our clinical observations, it is clear that millions of individuals are suffering (or have suffered) such experiences. This kind of abuse, captivity, and torture is not tolerated in any other group in our society, with the exception of some situations of domestic violence. It is ironic that in our country there are more strictures on operating a motor vehicle than on becoming a parent. In order to drive, one must obtain a license to do so. Driver education programs are universal in our schools, yet little or no training is formally available or seen as necessary to rear children. We assume that the ability to parent is somehow innate or at least learned from being adequately cared for as a child. In many instances, this assumption is correct, but in many other instances, it is tragically wrong. As a society, we give all adults the right to have children without providing them with the education to know how to do so, and we are complacent in allowing parents, many of whom are young and troubled, to struggle with the critical job of caring for children. The legacy of our complacency is a tide of human suffering and even death, which has resulted in untold human, financial, and moral costs to our society. We will require moral courage as a society to be willing to look openly where we previously have refused to see.

This volume is about the treatment of adults who have grown up bearing the scars of severe and chronic childhood abuse. These persons cannot just simply go on with their lives; this kind of abuse cannot be forgotten, disregarded, or left behind, and it continues to have profound effects in almost every domain of their existence. Severe and long-standing trauma introduces a profound destabilization in the day-to-day existence of many victims. They feel unpredictably assaulted by unwanted thoughts, feelings, and reminders of abuse. They are tormented by chronic anxiety, disturbed sleep, and irritability. They have symptoms that alter their perceptions of their environment, disrupt their cognitive functioning, and interfere with a sense of continuity in their lives. They are subject to powerful impulses, many of which are destructive to themselves or others. They have explosive emotions that they cannot always control. They experience self-hate and self-loathing and feel little kinship with other human beings. They long for a sense of human connection but are profoundly alone, regarding other people with great mistrust and suspicion. They want to feel understood but cannot even begin to find the words to communicate with others about their most formative experiences. They wish for comfort and security but find themselves caught up in a world of struggle, hostility, disappointment, and abandonment that recapitulates their early lives.

The therapists and other mental health professionals that treat these patients become a part of this world. Together with their patients, clinicians struggle to provide support, comfort, understanding, and change. Using themselves and the treatment as catalysts for change, clinicians attempt to provide the structure through which victims of childhood trauma may begin to undo the devastation of their early lives and go on to grow and flourish in the world. Given patience, understanding, skill, good judgment, determination, and sometimes just plain luck, survivors of profound child abuse and their therapists who ride this therapeutic roller coaster may survive to end up on solid ground, with a newfound stability and hope for future growth and fulfillment.

1 Portions of this chapter were adapted from “Trauma and Dissociation: 20 Years of Study and Lessons Learned Along the Way” (Chu & Bowman, 2000).

2 “Shengold’s use of the word delusionally does not assume a psychotic process or a defect in perception, but rather the practiced ability to reconcile contradictory realities” (Summit, 1983, p. 184).

3 There are approximately 67 million children in the United States under the age of 16. If unwanted sexual contact occurs in 1 in 20 children, 3.35 million would be victims during the course of their childhood. Assuming that all cases of sexual abuse occur only in one year during a child’s lifetime, there would be 209,000 cases per year.

4 Even in the post–World War II era, it was questioned as to whether abreaction alone was effective for combat-related trauma. See Horowitz’s Stress Response Syndromes (1986, pp. 118–120).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree