INTRODUCTION

The goals of medical practice based exclusively on cure and restoration of function are frequently called into question when patients are irreversibly ill and potentially dying. New goals, such as pain and symptom management, enhancing quality of life, and finding meaning in the face of death may take precedence, becoming an increasingly important part of the treatment plan. Some clinicians may wonder if death is something to be fought at all costs, or if relieving suffering is a central part of our responsibility as clinicians.

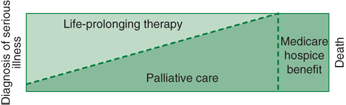

Enhancing the quality of life for those afflicted with serious chronic illness is the cornerstone of the rapidly developing specialty of palliative care. As illustrated in Figure 40-1, palliative care can be provided alongside aggressive treatment of a patient’s underlying disease, but as the patient becomes sicker and closer to death, palliation often becomes the primary objective.

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

Ella, a 71-year-old woman, develops pains in her lower chest for a month before visiting her personal physician. When a chest film shows several nodular masses suggestive of widespread lung cancer, the physician phones Ella and tells her there is a problem, making an office appointment for the next day. At this visit, the doctor discusses the results of the chest film with the patient and her son. Ella, having long suspected she might get lung cancer from smoking heavily, weeps openly upon hearing the results. Bronchoscopy is recommended, and she is referred to a pulmonologist. Bronchoscopic biopsies show a small-cell lung cancer. The pulmonologist refers Ella to an oncologist who recommends chemotherapy.

The patient and her son return to her primary care doctor to discuss her options. Ella says she would like to proceed with chemotherapy but wants to stop it if she becomes too ill from the treatments. A Roman Catholic, she has discussed with her priest the morality of refusing extraordinary care, including feeding tubes, if she were to have a terminal condition. She has appointed her son as her health care proxy, and discusses her desire not to undergo cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The physician gives Ella a living will and a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) document; she and her son complete them together. She wants to try all other potentially effective disease-directed treatments, and she also agrees to have her pain and shortness of breath treated aggressively as well. She also knows that cure is very unlikely with this treatment, so she begins to work with a financial planner to get her affairs in order.

Ella undergoes chemotherapy for several months, but gradually grows thinner and weaker. She and her son visit her doctor, and they are told that treatment is not controlling the disease and that the only options left for cancer treatment are experimental. She is referred to a home hospice program and agrees to a plan that is now directed exclusively at relieving her suffering. Ella lives alone and does not want to die in her apartment. Neither does she want her son to have to provide home care for her when she becomes too dependent to live alone. She also wants to know whether she could move to a hospice house or a nursing home for the very last phase of her illness when she is unable to care for herself at home. Her doctor and her son agree to find other placement when the need arises.

When she becomes confused 1 month later and is unable to stay at home, she is admitted to a comfort care floor at a local nursing home. An intensive palliative treatment regimen is initiated, and she dies 2 weeks later with her son at her bedside, 6 months after the initial diagnosis.

Early after this patient’s initial diagnosis, she received palliative care alongside aggressive treatment of her disease. Withholding aggressive pain and symptom management until referral to hospice is misguided and unfair, depriving patients of optimal treatment of their suffering from the beginning of their illness. This “both/and” approach has been one of the most important conceptual breakthroughs for palliative care, for it allows quality-of-life issues to be addressed for all seriously ill patients, not just those who are referred to hospice. It also allows patients simultaneously to “hope for the best” (that even improbable or experimental treatment might affect their disease and prolong their life) and “prepare for the worst” (make sure that financial affairs are settled and consider religious or existential issues should they wish to do so). It may be easier for some patients to make the transition to hospice if they have had this “both/and” conversation with their physician from the start of their illness.

When a patient is given the diagnosis of a life-threatening illness, a wide spectrum of feelings may emerge, including denial, anxiety, fear, sadness, and anger. If practitioners are surprised by the diagnosis, feel as though they missed a clue to the diagnosis earlier on, or are discomfited by death, they may feel inclined to withdraw from the patient’s care or to minimize the meaning and impact of the diagnosis. The commitment not to abandon the patient requires that clinicians learn to work through their own feelings, become knowledgeable about palliative care, and recognize that the process of dying can be a unique spiritual and personal experience for both doctor and patient. The goal should be to form a partnership that will help the patient face the future with courage and dignity.

The goals of partnership and shared decision making are sometimes limited by strong emotional reactions as well as long-standing personality traits that can isolate the patient from the clinician, friends, and family. In addition, physicians may be unable to commit the time and energy needed to develop close personal contact with the seriously ill and dying patient. Clinicians need to realize that extraordinary effort is sometimes required to be a partner with patients and their families through what initially may be a vigorous fight against disease, but eventually may end in the patient’s death.

The goal of palliative care is to provide the best possible quality of life for patients and their family. Palliative care addresses the biological, psychosocial, and spiritual dimensions of suffering, emphasizing state-of-the-art pain and symptom management, as well as a fresh look at goals and prognosis. Unlike Medicare-sponsored hospice programs, palliative care does not require patients to give up on aggressive treatment of their underlying disease, to accept a prognosis of lesser than 6 months, or to accept palliation as the central goal of therapy. Thus, it allows “hospice-like” treatments to be made available to those seriously ill patients who want to continue some or all disease-directed treatments. For example, patients who are highly likely to die, but want to try improbable experimental therapy in hopes that it might prolong their lives, could receive palliative care, but would not qualify for a Medicare-sponsored hospice program. Hospice programs enroll patients with a terminal disease who are more likely than not to die within the next 6 months’ time once they agree to forgo curative treatments for their disease and focus only on improving quality of life. Palliative care allows better pain and symptom management, careful attention to quality of life, an examination of the goals of treatment, and an opportunity to provide a much broader range of patients’ reflection on issues of life closure. Unfortunately, the medical infrastructure that supports the patient and family receiving palliative care at home is much less comprehensive than the medical infrastructure supporting hospice.

Patients confronting a severe illness may opt for an all-out, disease-oriented medical treatment, or a trial of aggressive medical care with set limits (such as a DNR order). Optimally, both of these patient pathways would also receive palliative care consultation from the time of diagnosis. When undergoing time-limited trials of aggressive care, patients have the opportunity to gauge and discuss with their provider whether the suffering involved with the treatment, given the odds of success, is worth it. When treatments begin to fail, or if supposedly curative treatments become too burdensome, patients can stop at any time and consider a transition to an approach that emphasizes pure palliation with their palliative care provider. This would be the time to consider referral to hospice, where relieving symptoms and alleviating suffering take precedence over attempts to treat the underlying disease.

Hospice programs provide comprehensive care to dying patients, with a multidisciplinary team of nurses, physicians, social workers, volunteers, and clergy. These programs, which accept only patients who are more likely than not to die in the next 6 months and are willing to forgo disease-directed therapies and hospitalizations, help patients and their families live as fully as possible by providing quality palliative care. In the United States, only about 30% of deaths occur in hospice programs, and many of these patients are referred to a hospice too late in the course of their illness to take full advantage of the resources and supports available to them. The palliative care philosophy underlying hospice can be applied in a range of settings including acute-care hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, and within the homes of patients. The advantage of hospice programs is the expertise brought to techniques of palliative care by the multidisciplinary staff, as well as the added support for patient and family at home, including payment for palliative medications and medical equipment. In most outpatient hospice programs, the primary care physician and the hospice team form a partnership to care for the patient. The primary care provider, with whom the patient may have a long-term relationship, should be intimately involved in both the decision for hospice referral and the patient’s ongoing care. Once distressing symptoms are controlled, the hospice team may then help the patient find avenues for hope, meaning, and ways of saying good-bye.

At times it may be difficult to distinguish normal grief reactions to the dying process from pathologic states that may require consultation and special treatment. There is a natural sadness that human beings experience with regard to death. This sadness, which may be a way of preparing for death, has been called preparatory or anticipatory grief. Grieving over the loss of physical abilities, social position, and contact with pleasurable routines—whether one’s own or those of a loved one—is a natural reaction. The absence of grief over these losses may indicate denial and emotional numbing. Sharing and exploring the grief can help both the patient and the clinician enter into a relationship that acknowledges each other’s humanity. Having the courage to explore these feelings assists the patient in coming to terms with death and may prevent the isolation and subsequent clinical depression to which some patients are prone.

Distinguishing clinical depression from the natural grieving process that accompanies a terminal illness may be difficult, as they share many common symptoms. The vegetative symptoms of depression—fatigue, changes in appetite, sleep disorders, decreased sexual drive—are all common in serious illness. As much as 80% of the psychological symptoms that occur in cancer patients go untreated simply because it is difficult to diagnose depression in this population. Providers should have a high index of suspicion for depression in patients with serious disease. The affective and cognitive signs of depression, such as loss of interest, withdrawal, sadness, inability to concentrate, and hopelessness may be realistic assessments in the face of severe suffering, fear of a loss of dignity, and the expectation of death. Major depression should be considered when the cognitive symptoms of dysphoria, shame, guilt, isolation, or suicidal ideation seem out of proportion to the patient’s situation (see Chapter 25). Depression in the terminally ill can be very responsive to pharmacotherapy as well as counseling even when it is part of a normal reaction. Depending on the expertise of the physician and other members of the multidisciplinary team, more challenging cases of depression and anxiety should be referred to a mental health professional. Psychotherapists who are familiar with the dying process and are experienced with medically ill patients can provide an invaluable resource, both diagnostically and therapeutically, in the care of the terminally ill.

In terminal illness, patients frequently decline in health in a stepwise fashion. These transitions near the end of life result in feelings of loss for patients and their families, and provide the potential for personal growth and the acceptance of death. Progressive declines initially may be treated as another form of bad news, but they provide the opportunity for enhanced meaning and control in the dying process. Physicians caring for terminally ill patients must explore and work through these transitions with their patients. Questions that clinicians can ask their patients in exploring their views on end-of-life issues are listed in Table 40-1. These can be asked as hypothetical questions to explore the patient’s beliefs about life and death. In patients with more advanced illness, the questions and their answers may be highly relevant to immediate treatment decisions.

CASE ILLUSTRATION 2

CASE ILLUSTRATION 2

Carlos, a 70-year-old man, has been diagnosed with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. In exploring the treatment options with his physician, he is clear about wanting only palliative measures, and referral to a home hospice program is initiated. Carlos is not a verbal man, and discussions about death and dying meet with little response.

At first, periodic nursing visits are all that is needed. He has an antique tool collection and spends countless hours labeling and ordering the tools. His nurse talks to him about this process, which has come to symbolize his anticipatory grief. As he deteriorates, nursing visits become more frequent, and home health aides come to help with his personal care. Carlos gradually becomes bed bound. Although his family initially feels uncomfortable with his dying at home, a family meeting with the physician and hospice nurse sets up a rotation of visits to provide for both company and supervision. Children who had been estranged are in the rotation, and it becomes a time of family healing. Although little is explicitly said about his approaching death, the presence of family and talk about the tools provide a vehicle for saying good-bye. Carlos dies quietly at home with his family present.

Life support

|

Personal beliefs

|

Long-term care and support systems

|

Patients’ willingness and ability to enter into deep discussions about death and dying vary considerably; clinicians need to be flexible in their expectations about how much exploration is desirable or even possible. It is unusual for a life-long pattern of behavior to be altered by the dying process; therefore, those who lived very private lives may not be able to open up significantly at the end of life. For some, dying may be a time for personal growth, reflection, and meaning; but for others, personal factors and emotional reactions block an acceptance of death. The most frequently encountered of these reactions are denial, anger, depression, fear, and anxiety. These reactions may be present in different degrees and at different times in the dying process. Clinicians need to acknowledge, explore, and eventually understand what function the reaction is serving for the patient. Empathy, rather than withdrawal, is the way to deepen the patient–clinician relationship and create an atmosphere in which personal growth is more likely to occur (see Chapter 2).

CASE ILLUSTRATION 3

CASE ILLUSTRATION 3

At 68 years old, Albert has severe end-stage emphysema, complicated by mitral regurgitation, congestive heart failure, cardiac arrhythmias, alcoholism, and years of smoking. He lives with his wife, whom he has bullied and dominated throughout their 40-year marriage. He has been on home oxygen and has had multiple hospital admissions for shortness of breath.

Admitted to the emergency room with severe shortness of breath, Albert is found to have pneumonia and heart failure. He had previously decided not to have CPR and wanted “no part of any of those damned machines.” He is admitted to the hospital and treated with aggressive medical means but is not put on a respirator. Albert regularly yells and curses at the respiratory therapists, nursing staff, physicians, and his family for not taking care of him, for making him suffer, and for not being prompt enough with meals, medicines, and treatments. He insists that the only thing wrong with him is that the medicines are making him sick.

Efforts to engage Albert in a dialogue that explores his feelings meet first with an unwillingness to talk and then a life history of feeling abandoned, powerless, betrayed by employers, and subject to bad luck. He describes himself as an “ornery son of a bitch.” He fears lingering and suffering in the hospital, and although he hopes he will die quickly, he is also afraid to die. One of Albert’s fears is of being buried alive, a phobia fed by a television program he had seen about the difficulty of determining when someone was dead and the possibility of being sent to the undertaker while still alive. The anxiety of being trapped in a “tight” place is overwhelming to him.

Albert’s physicians had initially resisted placing him on anxiolytic drugs or narcotics out of fear they would compromise his breathing. The palliative care consultant recommended that both be started, and reassured both the treating physicians as well as the patient and family of the safety and effectiveness of these treatments as long as they are started at low doses. Low-dose opioids and anxiolytic medications are eventually started around the clock, and his dyspnea and anxiety are dramatically improved. Placed in a room with a large picture window to the outside, he spends long periods of time staring out the window. His complaints diminish and he seems much more relaxed. He allows the hospital chaplain to visit and to pray with him, though he does not otherwise want to talk about the nearness of death or any regrets he has about his life. He eventually tells his wife he has suffered enough, and does not want to live any longer. He gradually becomes more confused as a result of the rising carbon dioxide levels and dies several nights later.

Patients with difficult personality traits who are experiencing the dying process can be especially challenging to caregivers. As represented on palliative care teams, the use of multidisciplinary specialties to brainstorm potential approaches and to share expertise may facilitate providers’ commitment not to abandon these particularly challenging patients and families.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree