RELEVANCE OF BEHAVIOR TO MEDICAL PRACTICE

Human behavior has a major impact on health and well-being. The patients that you see in medical practice are likely to have behaviors (e.g., smoking, drinking, and eating habits) that place them at risk of developing chronic disease. Equally likely, they may have psychological problems (e.g., depression) that impair their quality of life and undermine their motivation to follow your treatment recommendations. Moreover, if you treat families and see the same patients over many years, you may observe unhealthy behaviors long before you see the emergence of biological risk factors like hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or hyperglycemia. By helping your patients to address unhealthy behaviors, you have the opportunity to help them prevent the onset or worsening of chronic diseases. Just as in evidence-based medicine, you should know how to find and appraise the evidence base for behavioral (nondrug, nonsurgical) treatments, so you can help your patients with the most appropriate behavioral treatment option. Below is a case you might encounter in the primary care clinic.

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

CASE ILLUSTRATION 1

A 43-year-old man presents for a preventive care visit. He has not had any preventive care in over 5 years but at an urgent care visit 4 months ago he was told he had high blood pressure. His past medical history is remarkable only for mild eczema. He is married, has two children, and works as an attorney. He says his work is sometimes stressful but denies a depressed mood or loss of interest in leisure activities. He has no difficulty sleeping. He recently cut back to about five cigarettes per day and has three to four alcoholic drinks almost every night. He does not exercise regularly, but walks about 5 minutes twice a day to the train. He does not follow any particular diet: breakfast is usually coffee and toast; lunch is fast food or a deli sandwich; he snacks on cookies or pastries at work. His wife cooks “healthy food” sometimes and they order from restaurants frequently. On physical examination his weight is 207 lbs with a body mass index of 29.7 kg/m2. An average of three office blood pressures is 139/88 mm Hg. The rest of the examination is normal except for an eczematous rash on his arms. As you prescribe triamcinolone cream for his rash, you consider how best to counsel him about behavior change. The list of changes you think would be beneficial include: (1) stopping smoking; (2) reducing total calories; (3) following a diet low in sodium and high in vegetables, fruits, whole grains, and nonfat dairy products; (4) reducing saturated fat in his diet; (5) reducing alcohol use to no more than two drinks per day; and (6) increasing the amount of moderate-intensity physical activity he does by an additional 90–120 minutes each week.

APPLYING EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICE IN PRIMARY CARE

This patient has several risk factors and behaviors that put his health at risk and that are potential targets for behavior change interventions. You are probably familiar with how to practice evidence-based care when making medical decisions about the use of medications or procedures. There is also a scientific evidence base about how to treat most unhealthy behaviors. For the purposes of this chapter, we use the broader term “evidence-based practice” (EBP) that includes both traditional evidence-based medicine and evidence-based behavioral practice.

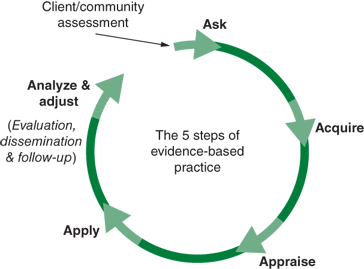

A practical way to approach EBP is by using a 5-step process better known as the “5A’s,”: Ask, Acquire, Appraise, Apply, and Analyze & adjust (see Figure 44-1).

The first step is to ask focused questions that can be answered through review of the scientific literature. Two kinds of questions connect health care providers with the knowledge base needed to offer best preventive care. The first (prognostic questions), asks which factors (i.e., biomarkers, behaviors, environmental conditions) convey risk or protection with respect to the likelihood of developing a chronic disease. The second (treatment questions) asks which treatments are most effective at reversing disease risk factors and promoting health protection.

Early in their careers, most physicians become familiar with the evidence base that evaluates which biomarkers warrant consistent clinical attention because they are risk factors for the development of chronic disease. They also learn to monitor and treat elevated cholesterol, blood pressure, and glucose to slow the patient’s progression toward clinical disease. For disease prevention to be effective, it is important for physicians to recall that many unhealthy behaviors (e.g., substance use, physical inactivity, overeating) warrant as urgent attention as risk biomarkers. By asking prognostic questions and consulting the scientific literature, you can master the knowledge base that supports the contention that lifestyle behaviors are just as strongly associated as risk biomarkers with the onset of disease. With that awareness, you can then inquire about the best ways to treat unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.

Next steps in the EBP process are to acquire the evidence and critically appraise it for its quality and relevance to your patient. As a health care practitioner, you are a consumer of research; sometimes you will look for primary research evidence such as individual research studies, including clinical trials. More often you will turn to a secondary, synthesized evidence base that has been assembled in the form of systematic reviews.

Much research exists about the lifestyle risk behaviors and treatment options for the patient described in the case. This evidence has often undergone systematic reviews to develop evidence-based treatment guidelines. For example, the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree