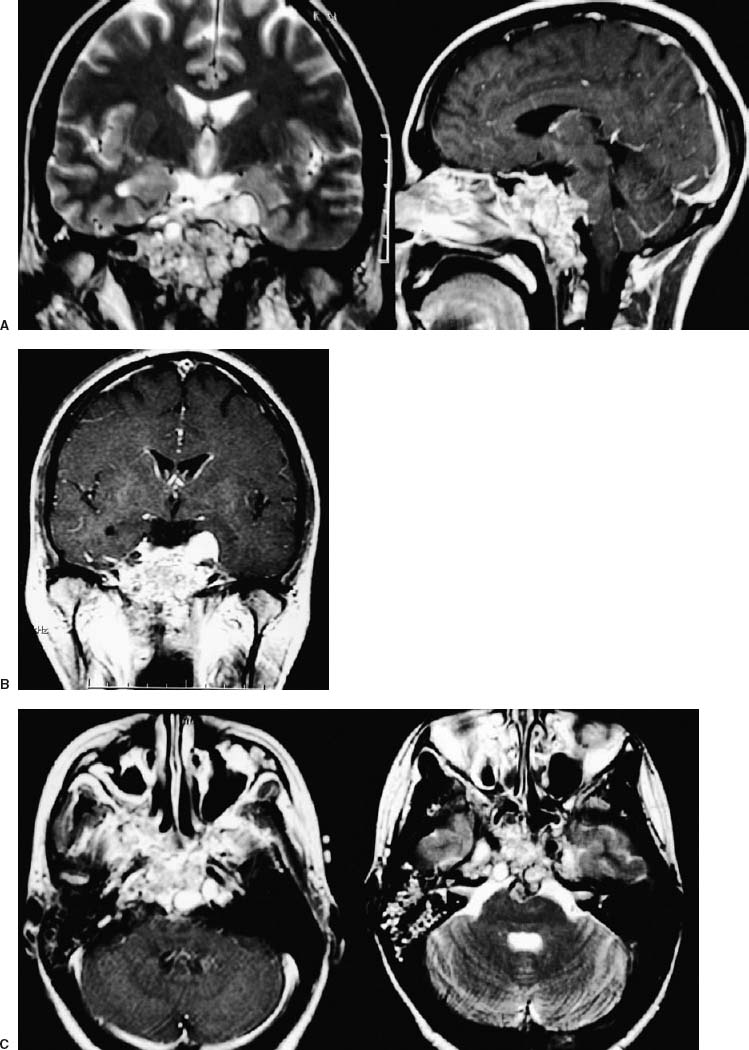

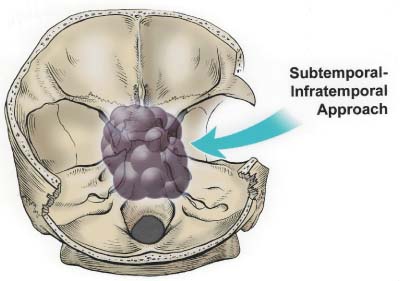

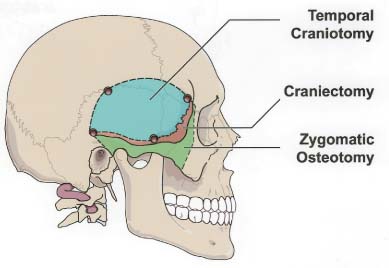

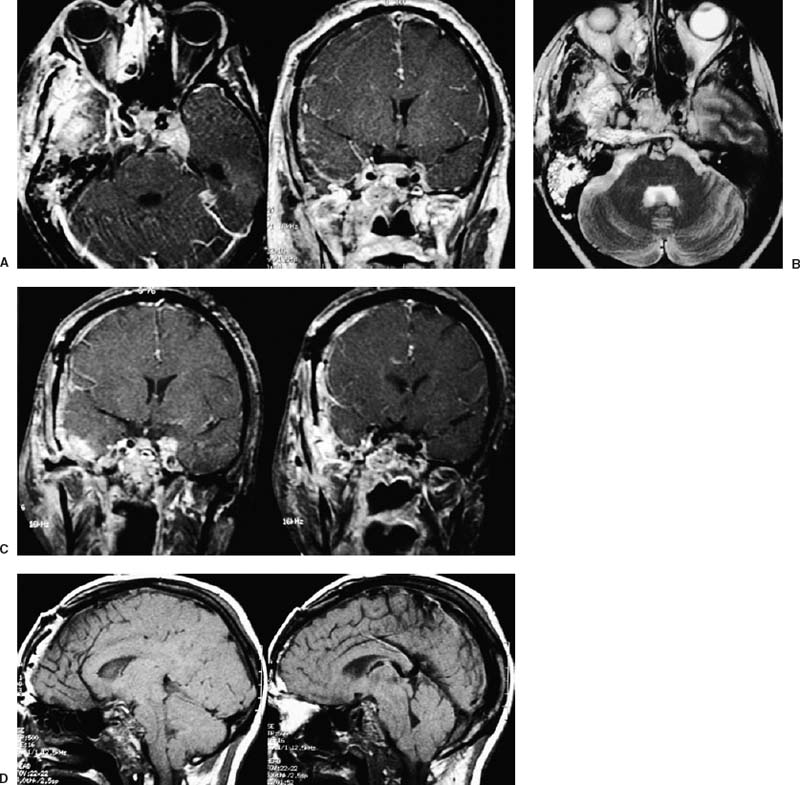

55 Diagnosis Extensive recurrent clivus chordoma Problems and Tactics The patient presented here is a young woman with a history of an extensive and recurrent skull base chordoma, for which she had undergone two partial resections with proton beam radiation between the surgeries in another institution, both via sublabial transmaxillary approach. Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after these two procedures showed regrowth of the residual tumor with worsening of her symptoms. She was then referred to us for the management of this extensive clivus chordoma. Keywords Extensive recurrent clivus chordoma, three-stage microsurgical resection The patient is a 34-year-old woman with a history of an extensive skull base chordoma. Her initial symptoms started ~6 months prior to the first medical consultation. These included blurry vision, neck pain with spasm, and dizziness. With these symptoms she was initially diagnosed to be stressed from work. Her symptoms worsened over time and she also developed a right-sided hearing difficulty. The patient then started having double vision, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head was ordered by an ophthalmologist. An extensive clivus lesion consistent with chordoma was discovered with this MRI and she was referred to another neurosurgeon for surgical management of this lesion. First, the patient underwent a partial resection of this giant chordoma through a sublabial transmaxillary approach. Two months postoperatively she underwent proton beam radiation therapy in 40 sessions. However, the tumor continued to grow; and her symptoms progressed with severe headaches and left-sided tongue weakness. She then underwent a second partial resection of the tumor through the same sublabial transmaxillary approach. This was followed by 30 sessions of hyper-baric O2 treatments. The tumor continued to grow, with the patient now developing right vocal cord palsy and difficulty swallowing and speaking. At this point she was referred to us for continuation of care. At our examination she had a partial right cranial nerve (CN) III palsy, a complete right CN VI palsy, decreased right hearing, right vocal cord palsy, and a left CN XII palsy. The patient had full strength in all extremities. She had difficulty with walking and balance and was losing weight. This was a very difficult and extensive skull base tumor (Fig. 55–1), and a three-stage resection via three different approaches was initially planned. FIGURE 55–1 (A–C) Magnetic resonance imaging at presentation (after the first two previous resections through transmaxillary approaches in an outside institution) showing the extent of the tumor recurrence. FIGURE 55–2 Drawing of the subtemporal–infratemporal approach used for the first-stage resection of the tumor. The first procedure was a partial resection of the tumor via a right subtemporal–infratemporal approach (Fig. 55–2). A right-sided orbitozygomatic, frontotemporal craniotomy (Fig. 55–3) was performed for this approach.1 After head fixation in a position slightly rotated (70 degrees) to the right and extension, the neuronavigation system was set up and the patient registered into the system with acceptable accuracy. A bicoronal incision, including exposure of the zygoma on the right side, was performed. A right-sided orbitozygomatic osteotomy and frontotemporal craniotomy were performed. FIGURE 55–3 Drawing of the craniotomy for the first-stage operation. From this point on the surgical microscope was used for the rest of the procedure. The superior orbital fissure was unroofed completely. The optic canal was partially unroofed as well. Medially, the anterior and posterior ethmoidal vessels were cauterized and divided and the right ethmoidal sinus was dissected to provide anterior access to the tumor. An extradural middle cranial fossa dissection was then performed. The mandibular and maxillary branches of the CN V were identified. The dura was incised gently over the lateral and outer layer of these nerves and gradually peeled away, including the temporal lobe, the peeling being in the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. The middle meningeal artery was cauterized. The mandibular condyle was mobilized after dissecting the vascular and fibrous tissue attachments posteriorly. At this point neuronavigation was used for orientation and localization of the tumor. The greater superficial petrosal nerve (GSPN) was identified by stimulation and facial electromyography and it was divided close to its foramen to avoid traction on the facial nerve. A high-speed drill was utilized at this point in the region of the petrous apex and the tympanic bone to isolate the petrous internal carotid artery (ICA). The eustachian tube was identified and transected at the junction of the cartilaginous and bony portions, and the genu of the petrous ICA was identified just medial to it. The horizontal and vertical segments of the petrous ICA were then gradually traced anteriorly and posteriorly. The eustachian tube itself was closed just medial to CN V3 by cauterizing the interior, packing with some fat and Surgicel, and closing with a stitch and a titanium hemoclip. The petrous ICA was completely mobilized through the carotid canal. After opening the periosteum, the fibrocartilaginous ring was sectioned and the petrous ICA completely mobilized forward. The petroclival bone was then drilled medial to the petrous ICA. The bone was very abnormal in this region, yellowish brown in some areas and with minimal bleeding. The bone was obviously invaded by the tumor, but not clearly containing cartilaginous tumor. Again the navigation system was used intermittently for localization. As we came through the petrous apex and clival bone medially, we identified the region where the tumor was clearly seen and was invading through the petroclival dura, which corresponded to the area seen on the MRI. The dura mater was invaded in this region. It was opened further to remove the entire intradural tumor. The arachnoid membrane was partially opened and some cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was drained. The ipsilateral CN VI, but not the basilar artery (BA), was seen. To avoid damaging it, we did not pursue visualizing the BA. By dissecting more medially, the petrous apex bone was completely removed. A fair amount of yellowish and cartilaginous tumor anterior to the clival dura was removed. In addition, we came down to the opposite side of the clivus and the opposite cavernous sinus (CS) region, using neuronavigation, removing some tumor from that region. Due to tumor adhesions and perhaps the previous surgery, the clival dura appeared very ragged in places. There was a considerable amount of clival bone remaining that was invaded by the tumor. By working posterior and anterior to the petrous ICA, more tumor was resected in this region using drill and rongeurs. This resection was continued until normal bleeding of the bone was seen, and it appeared nearly normal. At that time, it was felt that a piece of bone was left anteriorly, but this was not pursued further for fear of CSF leak. The goal was to allow the dura to heal prior to removing the rest of the clivus anteriorly. FIGURE 55–4 (A–D) Postoperative magnetic resonance imaging after the first-stage resection showing partial resection of the tumor.

Management of an Extensive Recurrent Clivus Chordoma

Clinical Presentation

Surgical Technique

Stage One: Preauricular Subtemporal–Infratemporal Approach

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree