6 OFF-LABEL USE

Abstract

Flow diversion has been demonstrated to be an effective treatment for cerebral aneurysms as well as a variety of other cerebrovascular lesions. Aneurysms and other lesions, which were previously considered untreatable or treated only with significant rates of morbidity and mortality, are now treated on a routine basis and with greatly reduced neurological sequela. The Pipeline Embolization Device (PED) received Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in 2011 for relatively narrow range of indications. FDA approved uses or “on-label” indications are restricted to large cerebral aneurysms from the petrous segment through the superior hypophyseal segment in adults. However, the application of flow diversion techniques has great value in lesions which do not fit strictly within this classification and in fact, the majority of cases that are treated with flow diversion currently are classified as “off-label” for one or multiple reasons. Some of the most common clinical situations where flow diversion is used in this manner include recurrent aneurysms previously treated with alternative endovascular means; aneurysms located in the posterior circulation or segments distal to the original proximal-indicated segment; and pathologies such as dissecting, fusiform, and blister-type aneurysms. Given that some of these conditions and specific lesions are subjected to treatment with this technology, the complexity and breadth of treatment possibilities has expanded greatly. In this chapter, we highlight some of the most common off-label indications and provide illustrative cases as examples.

6.1 Introduction

The Pipeline Embolization Device (PED) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in the United States on April 6, 2011, with labeling indications that specified its use for the treatment of wide-necked, large (≥ 10 mm), or giant intracranial aneurysms in the internal carotid artery (ICA), from the petrous segment through the superior hypophyseal segment, in adults 22 years of age or greater. This chapter focuses on the clinical use of these stents for indications outside the original FDA approval or “off-label” use as initially designated for the PED. At the time of this writing, no other flow diversion technologies are approved for use in the United States. It is noteworthy that the majority of cases performed with the PED are off-label. For instance, 53% of the 893 aneurysm treatments included in the IntrePED registry were performed for an off-label indication. 1

6.2 Recurrent Aneurysms

The recurrence rate after initial aneurysm coiling is not insignificant with rates reported in the range of 15 to 20%. 2 , 3 , 4 Furthermore, the recurrence rate for recoiling of previously coiled aneurysms may be as high as 50%. 5 This makes these lesions a potentially attractive target for the off-label use of flow diversion devices. Daou et al utilized the PED in a series of recurrent aneurysms and of 30 previously coiled aneurysms with angiographic follow-up, and they found a rate of complete occlusion of 76.7% and near-complete (≥ 90%) occlusion of 86.7%. 6 Of the aneurysms treated with a PED, only 6.7% required retreatment.

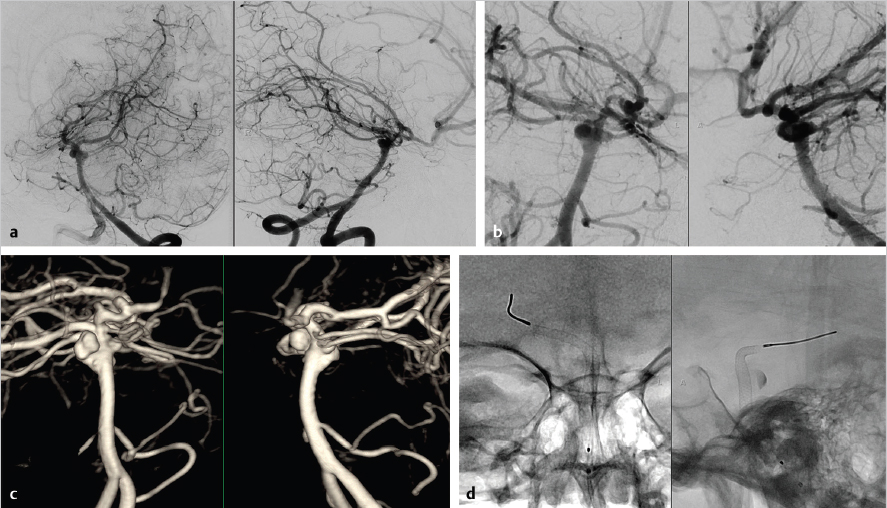

Another frequent off-label application of flow diversion is, as a rescue strategy after treatment failure, using a stent-assisted coiling with a nitinol self-expanding stent ( Fig. 6.1). Recurrent aneurysms that have been previously treated with stent-assisted coiling can be difficult to access with a microcatheter due to endothelialization of the coils and stents. Flow diversion offers the advantage of avoiding the need to access the aneurysm through the hardware. However, this application is often challenging technically due to the difficulty in navigation of the microcatheter and flow diverter through the existing stent, obtaining adequate vessel wall apposition, or successful expansion of the flow diversion device if it becomes entangled in the preexisting stent(s) and coil construct. It is also worth noting that in the labeling indications ( Table 6.1), one of the four listed contraindications for use is the presence of a preexisting stent in the parent artery at the target aneurysm location.

Indications |

Large or giant intracranial, wide-necked aneurysms |

Anterior circulation, from petrous segment of ICA to superior hypophyseal artery |

Adults aged 22 or older |

Contraindications |

Patients with active bacterial infection |

Patients in whom dual antiplatelet therapy (aspirin and clopidogrel) is contraindicated |

Patients who have not received dual antiplatelet agents prior to the procedure |

Patients in whom a preexisting stent is in place in the parent artery at the target aneurysm location |

Abbreviation: ICA, internal carotid artery. |

The use of a PED, however, has been reported in conjunction with the Neuroform stent, Enterprise stent, and the Leo + stent. Heiferman et al reported a series 7 of 25 aneurysms for which prior stent-assisted coiling had failed. Twenty-four of the 25 aneurysms were able to be treated and at 12-month follow-up, angiography showed Raymond class I obliteration in 38% (9 aneurysms) with all treated cases demonstrating decreased filling on follow-up imaging. Daou et al also reported a series of 21 patients with recurrent aneurysms initially treated with stent-assisted coiling. 8 The complete occlusion rate was 55.6%, which was a significantly lower obliteration rate than their own series of recurrent aneurysms that were originally treated with coiling alone. The retreatment (11.1%) and complication rates (14.3%) were also higher.

The majority of the cases treated in the aforementioned series involved aneurysms in the anterior circulation only. In addition, the reported complication rates (6–9%) are slightly higher in these series than the complication rates reported for recoiling procedures (1–3%). These results point to a potential cost for the higher occlusion rates when using flow diverters following stent-assisted coiling.

6.3 Ruptured Aneurysms

The treatment of ruptured aneurysms was traditionally believed to be contraindicated, given the gradual rate of aneurysm thrombosis resulting from flow diversion. It was believed that the risk of short-term morbidity and mortality, principally from re-rupture, would be too great to justify flow diversion as a protective strategy. In addition, the requirement for dual antiplatelet therapy complicated any additional surgical interventions for the patient, that is, the management of hydrocephalus with external ventricular drainage and/or shunt placement. However, as experience has accumulated, it has been increasingly recognized that flow diversion may be a reasonable option and can be accomplished with an acceptable outcome rate for a subset of ruptured aneurysms, with a particularly challenging morphology ( Fig. 6.2). 9 , 10 Lin et al 9 published a series of 26 patients treated with PED in the setting of subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). Eight of the 26 patients were treated in a delayed fashion and all but 4 patients had dissecting, fusiform, or blister aneurysms. In addition, 12 of the 26 patients were treated with adjunctive coiling along with flow diversion to accomplish a more immediate and complete aneurysm occlusion. Perioperative complications were seen in 19.2% of patients with three mortalities. Follow-up angiography was available for 23 of the patients with a 78.2% rate of aneurysm occlusion. A more complete review of flow diversion for ruptured aneurysms is covered elsewhere in this book.

6.4 Distal Anterior Circulation and Posterior Circulation Aneurysms

There are currently ongoing clinical trials which may expand the approved indications, if confirmed to have similar outcomes as the original studies that were the basis for FDA approval. The Pipeline Premier Trial expanded the indications to include aneurysms located throughout the intracranial course of the ICA up to the terminus, the vertebral artery up to and including the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA), and aneurysms ≤ 12 mm in dimension. The follow-up collection period for the Premier Trial concluded in late 2016 with the hopes that these data may lead to broadening of indications to include the current clinical practice within the FDA-approved indications. It is also possible that if and when additional flow diversion devices are approved for use, the approved indications will be broader than the PED.

Currently, flow diversion with a PED can be an excellent, albeit, off-label solution for posterior circulation aneurysms ( Fig. 6.3, Fig. 6.4, Fig. 6.5). A proximal location of posterior circulation aneurysms reduces, but does not eliminate, the risk of occlusion of a perforating vessel. Additionally, an endovascular treatment may eliminate the risks for what can be a challenging surgical approach. However, perforators are oftentimes not visualized during the procedure and the rate of complications may rise with the use of multiple overlapping devices. 11 Patency of large branch vessels such as the PICA has been reported in multiple series and is presumed to occur due to downstream demand maintaining anterograde flow. In a small series of vertebral artery aneurysms located on the V4 segment, 8 of 11 patients maintained PICA patency despite coverage with the PED at follow-up without evidence of clinical sequela. 12

Flow diversion has also been used effectively in more distal posterior circulation segments, where other treatment options would have distinct disadvantages ( Fig. 6.6). However, the initial experience with posterior circulation flow diversion, particularly with fusiform aneurysms, was filled with significant morbidity and mortality from both perforator infarcts and delayed ruptures. 13

Albuquerque et al, 14 however, published a series of 17 cases with more than 90% complete or near-complete occlusion. Only one patient experienced a significant complication related to a ventriculostomy hemorrhage. Munich et al 11 reported a series of 12 fusiform vertebrobasilar aneurysms treated with PED and reported one death and two significant new neurological complications, both of which improved significantly at follow-up. At follow-up, 90% of the cases were angiographically occluded. In a subsequent reanalysis of the treatment indication after their initial cautionary report, the University of Buffalo group published 15 a series of 12 patients with fusiform vertebrobasilar aneurysms treated with flow diversion with 50% of the cases treated with adjunctive coiling. At last radiological follow-up (14-month average), all 12 patients had patent devices and complete aneurysm occlusion. Two patients did require a second treatment with a PED to achieve complete occlusion. Only one patient suffered a perforator infarct. In these and other reports, 16 multiple factors are cited which may have improved the outcomes and make posterior circulation aneurysm viable treatment targets. These strategies included adjunctive coiling to limit delayed rupture, limiting the number of devices utilized as longer Pipeline device lengths became available, and meticulous attention to dual antiplatelet efficacy and adherence. Although this represents small retrospective case series, the results lend support to the use of flow diversion in cases where alternatives, such as stent-assisted coiling, clip reconstruction, or deconstructive procedures with or without bypass, are not feasible or carry similar substantial risks.

The distal anterior circulation is another area of off-label use that has expanded as experience has been gained ( Fig. 6.7, Fig. 6.8, Fig. 6.9). Initial published reports 17 , 18 did not seem to validate concerns regarding coverage of A1 and M1 segments and perforators. Additionally, the technical feasibility of navigating devices into smaller distal vessels has been well documented. Lin et al 18 reported successful treatment of 27 distal anterior circulation aneurysms with PEDs in a series that included fusiform (15), dissecting (5), and saccular (8) aneurysms. They reported a perioperative complication rate of 10.7% and complete aneurysm occlusion in almost 80% at an average follow-up of 10.7 months. It is noteworthy that 10 of the 27 cases had failed previous treatment with either clipping or coiling.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree