Vignette 6

Sleepwalking

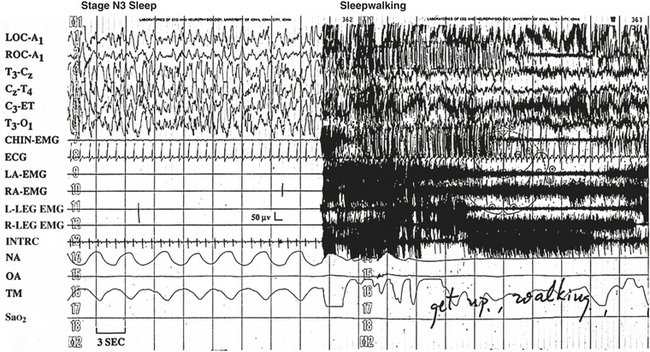

A 22-year-old college student under significant psychosocial stressors reported being completely amnestic for spells of confused arousals with nocturnal wanderings that had been witnessed by her roommates.1,2 Formal split-screen, video-polysomnographic (PSG) analysis captured multiple confusional arousals from stage N3 sleep associated with standing and attempting to walk (Vignette Fig. 6.1). The split-screen PSG/video analysis allows one to see how the patient exhibits a very brief confusional arousal from N3 sleep, associated with nonsensical vocalizations, after which she has another confusional arousal from stage N3 sleep, tries to remove her scalp electrodes, then stands and attempts sleepwalking.

VIGNETTE FIGURE 6.1 Polysomnographic tracing of the young woman in the video as she experiences a classic sleepwalking episode from stage N3 sleep (see the technician’s note, “get up walking”). LOC, Left outer canthus; ROC, right outer canthus; A1, left ear; T, temporal; C, central; ET, ears tied; O, occipital; EMG, electromyogram; ECG, electrocardiogram; LA, left arm; RA, right arm; L-LEG, left leg; R-LEG, right leg; INTRC, intercostal EMG; NA, nasal airflow; OA, oral airflow; TM, thoracic movement; SaO2, arterial oxygen saturation. (Modified from Dyken ME Yamada T, Lin-Dyken DC. Polysomnographic assessment of spells in sleep: nocturnal seizures versus parasomnias. Semin Neurol. 2001;21:377-390.)

Discussion

In childhood, sleepwalking has a prevalence up to 17%, peaking between 8 and 12 years of age, with a strong genetic factor in 65% of cases.3,4 Although sleepwalking, when it occurs, usually resolves by puberty, it continues to affect an estimated 4% of the adult population. In adults, violent behavior and injuries occur more frequently in men, especially if there is an external attempt to fully awaken the patient during an event.5 Unlike the relatively nonpernicious nature of childhood sleepwalking, it has been suggested that sleepwalking in the adult population is more closely associated with psychiatric illness.6

Sleepwalking is a parasomnia. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, second edition, describes parasomnias as undesired physical phenomena that occur during entry, within, or upon arousal from sleep. Parasomnias are usually associated with a state of central nervous system activation, evidenced as an elevation of autonomic and skeletal muscle activity, often with an experiential element.3 The differential diagnosis for sleepwalking includes seizures and a variety of sleep-related movement disorders not considered parasomnias.

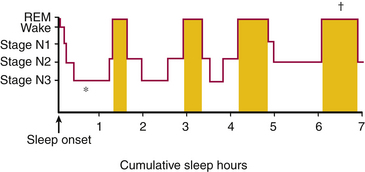

Sleepwalking, confusional arousals, and sleep terrors are also defined as “Disorders of Arousal (From NREM Sleep).”3 Much of the first third of a normal night’s sleep is spent in stage N3 sleep (Vignette Fig. 6.2), and sleepwalking frequently occurs at the end of the first or second period of stage N3 sleep.2,3 As such, consistent sleepwalking-like behaviors that routinely occur soon after sleep onset can help in narrowing the differential diagnostic considerations. Adolescent sleepwalking may be preceded by early childhood confusional arousals.3 In any given sleepwalker a single PSG may not capture sleepwalking. Nevertheless, a suggestive clinical history and PSG documentation of confusional arousals can support the diagnosis of suspected sleepwalking.

VIGNETTE FIGURE 6.2 This histogram shows the general progression of sleep stages throughout a relatively normal night of sleep in a young adult, with the majority of consolidated stage N3 sleep occurring early in the night (asterisk) and the majority of consolidated/relatively prolonged stage R sleep occurring in the early morning hours (dagger) relatively close to the expected waking time. (Modified from Dyken ME, Lin-Dyken DC. Parasomnias. In: Yamada T, Meng E, eds. Practical Guide for Clinical Neurophysiologic Testing: EP, LTM, IOM, PSG, and NCS. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkens; 2011:260-277.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree