Vignette 8

Sleep Terrors

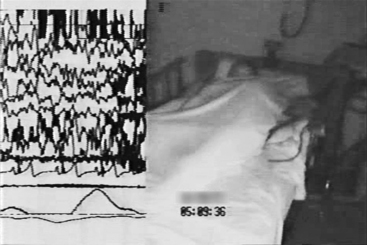

A 16-year-old girl presented with recurrent spells from sleep associated with combative behavior, with a concern for nocturnal seizures.1 During one event she reportedly fell down the stairs and chipped some teeth. A formal polysomnogram (PSG) captured one of her classic events, arising from stage N3 sleep (Vignette Fig. 8.1). During this spell she immediately began to tear off her electrodes, and attempted restraint by the technician exacerbated the violent behavior, which was evidenced as combative physical activity in association with loud, guttural vocalizations. The patient was completely amnestic for this event.

VIGNETTE FIGURE 8.1 A 16-year-old girl with recurrent spells of nocturnal combative behaviors for which she was amnestic. This figure shows the split-screen video analysis of the polysomnogram that captured a classic sleep terror that began in stage N3 sleep.

Discussion

Sleep terrors are parasomnias. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders: Diagnostic and Coding Manual, second edition, describes parasomnias as undesired physical phenomena that occur during entry, within, or upon arousal from sleep. Parasomnias are usually associated with a state of central nervous system activation, evidenced as an elevation of autonomic and skeletal muscle activity, often with an experiential element.2 As such, the differential diagnosis for sleep terrors includes seizures and a variety of sleep-related movement disorders not considered parasomnias.1,2

Sleep terrors, sometimes referred to as pavor nocturnus in children and as pavor incubus in adults, are abrupt episodes that arise from sleep in association with motor agitation, vocalization, and extreme fear, often with hysterical bloodcurdling screaming and crying.1,2 Autonomic hyperactivity is also associated with these events, as evidenced by diaphoresis, mydriasis, tachypnea, and tachycardia.2 Patients appear alert with open eyes, but attempts to engage them are usually unsuccessful and may prolong the event.1,2

The onset is usually between 4 and 12 years of age, with a prevalence in children up to 6.5%.2,3 Although sleep terrors generally resolve in adolescence, the prevalence may reach 2.6% in the adult population up to 65 years of age.2 Precipitants of sleep terrors include those typical for the other parasomnias classified as “Disorders of Arousal From NREM Sleep” (confusional arousals and sleepwalking). These include medications, stress, illness, insufficient sleep, alteration of the sleep schedule, or a change in sleep environment. Although not associated with psychopathologic conditions in children, sleep terrors in adults on occasion have been reported in patients with bipolar, depressive, and anxiety disorders.2,4

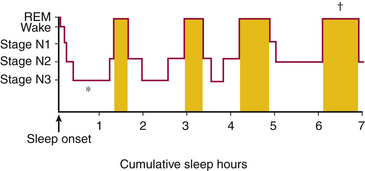

Although spells associated with fearfulness also occur with nightmares, several features distinguish them from sleep terrors. Sleep terrors usually occur relatively early after sleep onset, characteristically toward the end of the first or second period of N3 sleep, whereas nightmares tend to occur more frequently in the early morning hours, corresponding with REM sleep (Vignette Fig. 8.2).1,2 If a patient is able to give details of a frightening dream upon awakening, the event is more likely a nightmare. Although sleep terrors are associated with amnesia, some individuals may retain memory of a feeling of fear or threat as the episode resolves. In such cases the patient is prone to developing clinophobia (the fear of going to bed) with sleep-onset insomnia, a stress that could exacerbate further sleep terrors.5

VIGNETTE FIGURE 8.2 This histogram shows the general progression of sleep stages throughout a relatively normal night of sleep in a young adult, with the majority of consolidated stage N3 sleep occurring early in the night (asterisk) and the majority of consolidated/relatively prolonged stage R sleep occurring in the early morning hours (dagger) relatively close to the expected waking time. (Modified from Dyken ME, Lin-Dyken DC. Parasomnias. In: Yamada T, Meng E, eds. Practical Guide for Clinical Neurophysiologic Testing: EP, LTM, IOM, PSG, and NCS. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkens; 2011:260-277.)

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree