OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Describe the characteristics and distribution of medically vulnerable populations worldwide.

Review common challenges faced by health systems globally in assessing and meeting the needs of medically vulnerable populations.

Highlight best practices from across the world in how health systems are addressing the needs of medically underserved populations.

Identify core competencies for health professionals to promote health equity locally and globally.

INTRODUCTION

Management of health care for medically vulnerable and underserved populations shares a common mission with the growing field of global health. The global health perspective “places a priority on improving health and achieving equity in health for all people worldwide.”1 Addressing the health needs of marginalized populations is fundamental to this orientation.

Care of domestic medically vulnerable populations represents a local facet of global health. The upstream causes of medical vulnerability and the health system challenges in locating those most at risk and providing them with appropriate and affordable health care are common across the world. Many students and health professionals with an interest in global health are also committed to caring for domestic underserved populations.2,3 Framing the care of medically vulnerable and underserved populations in a global context opens opportunities to share solutions applicable to serving vulnerable populations in any country.

In this chapter, we use a global perspective to present unifying themes in addressing the needs of diverse underserved populations. We start by describing the causes, characteristics, and worldwide distribution of medically vulnerable populations. We then review health system challenges in assessing and meeting their needs, and illustrate solutions to some of these challenges from “best practices” from around the world. We conclude by describing competencies for health professionals to promote health equity locally and globally.

CAUSES OF MEDICAL VULNERABILITY WORLDWIDE

Nassoro, 7-year-old boy, lives in rural Tanzania and is undernourished. Because of severe droughts, he only receives one nutritious meal per day through the school program he attends.

Aisha, 9-year-old girl, lives in poor neighborhood of a large US city and is obese. Her family cannot afford to eat balanced meals and relies on a limited range of low-cost foods with high caloric, processed food of low nutritional value.

Several factors render populations vulnerable and result in health inequities, the greatest of which is poverty. For example, poverty results in food insecurity for millions of people across the world. Compounding factors contributing to health inequity globally include unhealthy and unsafe environments, destabilized societies and homelessness, and violation of human rights.

Both under- and overnutrition result from food insecurity—the absence of enough, safe, nutritious, and socially acceptable food. Food insecurity may be chronic, seasonal, or temporary, and may occur at the household, regional, or national level. In low- and middle-income countries, the root causes of food insecurity include poverty, war and civil conflict, natural disasters, corruption, barriers to trade, low levels of education, and national policies that do not promote indigenous crop production for local consumption and equal access to food for all. In higher-income nations, the primary causes of food insecurity are poverty and public subsidies for mass-produced, agricultural mono-crops such as corn, which render high caloric processed foods less expensive than more nutrient-dense, perishable food, such as fruits and vegetables. A globalized food economy dominated by large agribusiness interests contributes to food insecurity across the world (see Chapter 26).

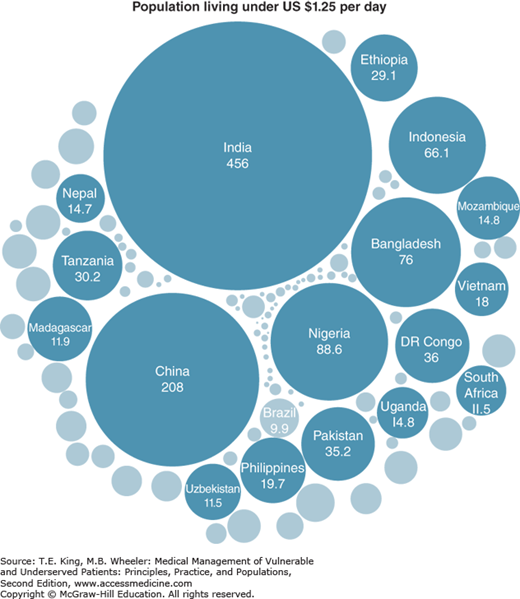

In 2010, 21% of the world’s population lived on less than US $1.25 a day.4 These 1.2 billion people live in absolute poverty deprived of basic human needs, such as access to food, water, sanitation, clothing, shelter, health care, and education. The burden of poverty has shifted from low- to middle-income countries. In 1990, 93% of the world’s 1.8 billion poor lived in low-income countries, whereas today 72% of poor people live in middle-income countries.5 Half of the world’s poor live in India and China; one quarter in other middle-income countries, primarily Pakistan, Nigeria, and Indonesia; and only a quarter live in 39 low-income countries (Figure 7-1). Worldwide, poverty is no longer primarily due to a lack of resources in “poor” countries, but due to economic inequality in countries that, as a whole, are no longer impoverished.

Figure 7-1.

Distribution of worldwide poverty by country (in millions of people). (Data from Sumner.5 Reproduced with permission from the Guardian Data Store.)

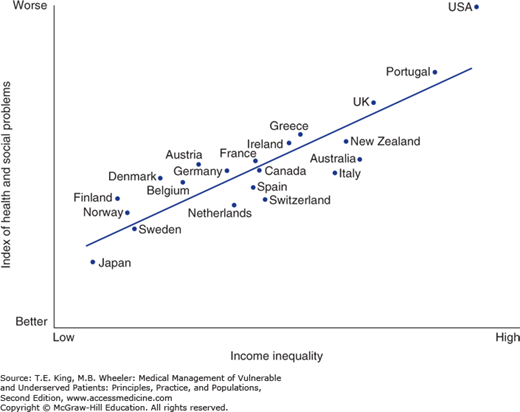

Poverty and health have a bidirectional association. Poverty leads to ill health because it forces people to live in environments that make them sick, without decent shelter, clean water, or adequate sanitation. Ill health, on the other hand, interrupts employment and can result in catastrophic household expenses that lead to poverty.6 As noted in Chapter 1, relative income inequality, and not only poverty in absolute terms, adversely influences health. Individuals living in relative poverty in more unequal societies experience worse health outcomes as compared to those living in more equitable societies.7 Within the Organization for Co-operation and Development, countries with greater relative income inequality have lower measures of physical health, mental health, drug abuse, obesity, teenage pregnancies, and child well-being, among other factors. Wilkinson and Pickett have demonstrated that among these countries, an aggregate measure of societal and health problems is worse in more unequal countries, with the United States faring particularly poorly in this regard (Figure 7-2).8

Environmental factors account for an estimated quarter of the global burden of disease and disproportionally affect the poor.9 Environmental risks include inadequate sanitation, indoor particulate exposure, and unsafe drinking water. For example, slum dwellers in urban areas in many nations do not have access to municipal water and sewage services, safe housing, health care, or other critical services. The rural poor face diminishing wildlife resources required for food.10 Natural catastrophes such as droughts and floods are a subset of environmental risk, which often result in the displacement of populations. These catastrophes are becoming more prevalent due to global climate instability. Climate change is aggravating environmental risks such as increased exposure to heat stress, air pollution, respiratory allergens, and infectious diseases.

Currently, one-third of the world’s poor live in “fragile” countries5—countries undergoing postconflict or political transition, situations of prolonged crisis or impasse and deteriorating governance. For example, nations such as Syria and the Central African Republic have recently experienced a series of crises which have resulted in the collapse of the state, interruption of public services, and human rights violations.11

Conflict and its aftermath undermine the ability of a country to operate basic civic functions such as rudimentary security operations and health and social services, and to ensure economic opportunities for its citizens. Health facilities in conflict areas can disintegrate when supplies cannot reach them and when the lives and livelihoods of health workers are threatened. For example, 6 years after the 1992–1995 conflict in the Republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina, displaced Bosnians were 15% less likely to be working relative to nondisplaced Bosnians.12 Additionally, displaced men experienced higher rates of unemployment, and displaced women were more likely to drop out of the labor force, raising concern for the long-term economic vulnerability of displaced persons. The implication of having one-third of the world’s poor living in fragile states is that normal health-care infrastructures cannot be relied on to reach medically vulnerable populations in these contexts.

Fragile states produce a ripple effect in high-income countries, as displaced persons often seek refuge in more economically and politically stable nations. For example, Europe is experiencing a surge of immigration from refugees seeking to escape traumatic conditions in the Middle East and North Africa, creating a humanitarian crisis challenging social, health care, and legal services. High-income countries also often have their own indigenously displaced populations in the form of homeless persons.

Leila is a Syrian mother forced to flee her home with her two children because of civil conflict. She lives in a camp along the Turkish border in precarious living conditions.

Tara is a homeless single mother of two who has fallen under the US federal poverty level because of catastrophic medical expenses. She lives in a homeless shelter for families.

Housing insecurity is multidimensional and describes a range of conditions including needing to move as a result of circumstances outside a person’s control, instability in housing circumstances, or feeling unsafe within the home and its environment. Housing insecurity entails lack of privacy and comfort as well as lack of supportive relationships and connection to the local community. Underlying all dimensions of housing insecurity is a perceived lack of control over circumstances of life, including finances, employment, health, and family stability. The consequence of living with this combination of insecurities leads to focusing on day-to-day survival. Poor housing conditions have been linked to multiple negative health outcomes in both children and adults. Housing insecurity has been associated with poor health, lower weight, and developmental risk especially in children.

Discrimination and human rights violations adversely impact health across the globe. People face discrimination based on many factors, including race, religion, gender, age, and sexual orientation, often leading to severe violation of human rights through forced labor practices, absence of free movement or free speech, and torture or degrading treatment. Many individuals are subject to virtual slavery through illegal forced labor practices, to which children are particularly susceptible.13,14 Officially sanctioned discrimination with egregious denial of human rights occurs in some countries, such as the recent legislation in Uganda imposing harsh criminal penalties for homosexual acts and educational outreach. But discrimination in various forms is ubiquitous in cultures and societies across the globe. Systematic violations of human rights are often coupled with outright denial of access to health care or marginalization of populations in a manner that impedes access to care.

Human rights violations do not necessarily respect national borders. An example is human trafficking—trade in humans, most commonly for the purpose of sexual slavery, forced labor, or commercial sexual exploitation.13 The United States is a major destination country for human trafficking, with 14,500–17,500 victims trafficked into the United States annually.15 The health consequences of human trafficking include sexually transmitted infections, including HIV, and permanent damage to reproductive organs.16 Victims of trafficking often have psychological trauma, resulting in chronic anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder. Victims may be coerced into, or willingly surrender to, drug use in an attempt to alleviate their distress.17 Perpetrators of sex trafficking often prevent their victims from accessing health services. When victims do seek care, they may be inhibited from revealing their circumstances due to fear of reprisal.

HEALTH SYSTEM CHALLENGES

Many countries fall short of being able to provide even the most basic package of essential medical services to vulnerable populations. The reasons for this include difficulties for health services in locating and serving some population groups, lack of appropriately trained and deployed health-care personnel, inadequate health information systems, and lack of political will to achieve universal health-care coverage.

Health systems have difficulties tracking the health and health-care needs of people who do not have official records. Many people, particularly those born in rural regions of low-income countries, have never been included in national civil registration system; others drop off registration systems when they migrate without formal documentation or sanctioned residency status. Setel et al18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree