Abnormal Movements

BACKGROUND

Abnormal movements are best appreciated by seeing affected patients. If you are armed with the right vocabulary, most common abnormal movements can be described. However, many experts will describe the same movements in different ways—so journals about movement disorders come with video clips to illustrate the movements!

In most patients with movement disorder, the diagnosis depends on an accurate description of the clinical phenomenon.

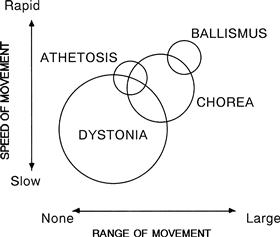

There is frequently a considerable overlap between syndromes, and several types of abnormal movement are often seen in the same patient—for example, tremor and dystonia in a parkinsonian patient on treatment.

The anatomy of the basal ganglia is complicated and wiring diagrams illustrating the connections between the various structures become more complicated as more research is done. Neuro-anatomical correlations are of limited clinical value as most movement disorders are classified as syndromes rather than on anatomical grounds. Correlations of significance include unilateral parkinsonism due to lesions of contralateral substantia nigra and unilateral hemiballismus due to lesions of the contralateral subthalamic nucleus or its connections.

In evaluating movement disorders, there are three aspects to the examination:

– the abnormal positions maintained

– the additional movements seen.

– the inability to do things: for example, a slowness in initiating actions (bradykinesia).

WHAT TO DO

Look at the patient’s face.

Look at the patient’s head position.

Look at the arms and the legs.

Ask the patient to:

• smile

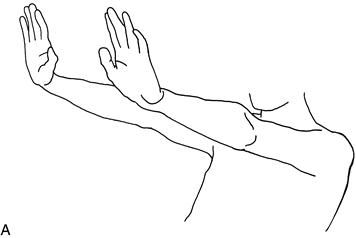

• hold his hands out in front of him with his wrists cocked back (Fig. 24.2A)

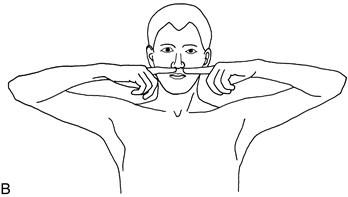

• lift his elbows out sideways and point his index fingers at one another in front of his nose (Fig. 24.2B)

If there is a tremor, note the frequency, the degree of the excursion (fine, moderate, large) and the body parts affected. Look for a tongue tremor (see Chapter 13).

Test eye movements (Chapter 9).

Test tone (Chapter 16).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree