chapter 13

Abnormal Movements and Difficulty Walking Due to Central Nervous System Problems

In the previous chapter difficulty walking that is related to peripheral nervous system problems was discussed. The first half of this chapter deals with the more common central nervous system problems that result in difficulty walking; the second half discusses abnormal movements affecting the face, head and limbs, some of which lead to difficulty walking.

DIFFICULTY WALKING

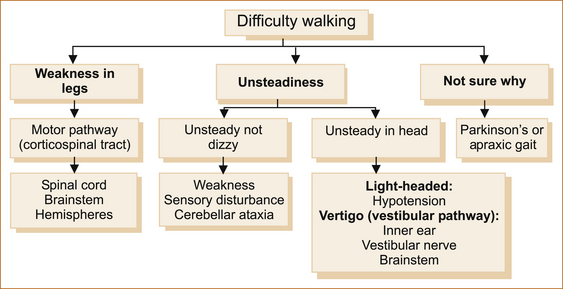

When a patient complains that they are have difficulty walking, simply ask if the difficulty relates to a sense of instability in the head or something wrong with their legs or if they are uncertain why they are having problems. Figure 13.1 shows the diagnostic possibilities in each of these three scenarios.

Difficulty walking related to weakness

The presence of weakness in the legs infers a problem involving the motor pathway, which extends from the motor cortex to the muscle.

Clues that the spinal cord is the site of the problem:

• Back or neck pain that coincides with the development of neurological symptoms in the lower limbs

• Alteration in sphincter function with constipation and/or urinary retention

• Altered sensation with a sensory level on the trunk (a strong indicator)

Clues that the brainstem is the site of the problem:

• Dysphagia (to a lesser extent)

• Ipsilateral facial sensory loss and contralateral loss to pain and temperature affecting the limbs (lateral brainstem involvement)

• A 12th, 6th or 3rd nerve palsy on the side opposite to the weakness points to the medulla, pons and midbrain, respectively (see Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’)

Clues that the cerebral hemisphere is the site of the problem:

• When there is upper motor neuron facial weakness in addition to the weakness in the arm and leg, the lesion must be above the mid pons on the contralateral side and, therefore, cannot be any lower in the brainstem or in the spinal cord. If areas in the hemispheres other than the motor pathway are affected, it may be possible to localise the lesion to the hemispheres, in particular the cerebral cortex.

• Dysphasia (dominant hemisphere lesions affecting the cortex)

• Visual field loss (hemianopia or quadrantanopia) if the visual pathways are affected

• Visual inattention if the parietal cortex is affected

• Cortical sensory signs (2-point discrimination, graphaesthesia, stereognosis or sensory inattention) (Other cortical phenomena are described in Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’.)

SPINAL CORD PROBLEMS

1. lesions external to the dura (traumatic spinal cord compression, prolapsed intervertebral discs, epidural abscess)

2. lesions beneath the dura but external to the spinal cord (neurofibroma, Chiari malformation)

3. intrinsic spinal cord problems (glioma, ependymoma, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, syphilis, arteriovenous malformation, spinal cord infarction and adrenomyeloneuropathy).

These are very rare conditions and are beyond the scope of this book.

The features that point to intrinsic cord pathology are:

• early development urinary or anal sphincter dysfunction

• early involvement of the spinothalamic tract

• suspended sensory loss, which is a classical feature of an intrinsic spinal cord problem where there is altered pain and temperature sensation in a pattern that resembles a cape with impaired sensation on the upper trunk but sparing the lower trunk and lower limbs.

• early sacral sensory loss occurs with extrinsic compression and sacral sparing is seen with intrinsic spinal cord lesions; the presence of radicular pain indicates lesions extrinsic to the dura.

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM): Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is the commonest cause of spinal cord dysfunction in elderly patients. It is also the commonest cause of paraparesis or quadriparesis not related to trauma. Repeated occupational trauma, such as carrying axial loads, genetic predisposition and Down syndrome all predispose to an increased risk of cervical spondylosis.

Cervical spondylosis relates to degenerative changes initially in the cervical discs with subsequent subperiosteal bone formation, referred to as osteophytes. Cervical disc protrusion or extrusion, osteophytes and hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum together result in spinal cord compression, and secondary spinal cord ischaemia can occur with severe compression. Rarely spondylolisthesis may occur and cause cord compression.

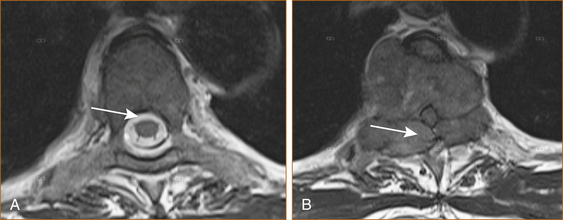

Cervical cord compression (see Figure 13.2) can be seen in younger patients with congenitally narrow spinal canals (10–13 mm). The spinal cord is stretched during flexion of the cervical spine and buckling of the ligamentum flavum occurs during extension of the cervical spine. Thus, repeated flexion and extension in the patient with significant canal narrowing may cause intermittent acute compression of the spinal cord, and it is thought that this may also account for the clinical deterioration seen in many cases of CSM [1].

FIGURE 13.2 MRI scan of A normal cervical spine and B spinal cord compression due to cervical spondylosis

The natural course of CSM for any given individual is variable and precise prognostication is not possible. Once moderate signs and symptoms develop, however, patients are less likely to spontaneously improve. Worsening occurs more commonly in older patients whereas patients with mild disability are less likely to worsen [1].

CSM can present in a variety of ways.

1. The commonest presentation is with the insidious onset of difficulty walking related to weakness and/or stiffness (due to spasticity). Some patients will have neck pain from the cervical spondylosis; pain in the arm related to nerve root compression is less common.

2. Older patients in particular may present with weakness and wasting of the small muscles of the hands related to nerve root compression, and the signs of spinal cord compression are noted when they are examined.

3. A presentation that is much less common is the central cord syndrome resulting from a hyperextension injury in the setting of cervical canal stenosis where the weakness is greater in the upper than the lower limbs with or without a suspended sensory loss (affecting the shoulders and upper torso like a cape) and urinary retention.

4. Patients with cervical cord compression may experience an electric shock-like ensation radiating down their back or into their limbs with neck flexion, the so-called L’Hermitte phenomena commonly seen in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS).

Thoracic cord compression: Thoracic spinal cord compression most commonly occurs with metastatic malignancy, less commonly with a thoracic disc, epidural abscess or extrinsic spinal cord tumour such as a meningioma or a neurofibroma. There is an aphorism that ‘a thoracic cord lesion in a middle-aged to elderly female is a meningioma (benign tumour arising from the meninges) until proven otherwise’. Back pain is rare with a meningioma, more common but not a universal feature of thoracic discs, but increasingly severe back pain occurs for on average 8 weeks or longer in 80–95% of patients who subsequently develop malignant cord compression [2]. Patients who are not known to suffer from malignancy, but who develop increasingly severe midline (especially thoracic) back pain, should be investigated promptly in the hope of preventing malignant cord compression.

Although initially the pain is localised to the vertebra, subsequent nerve root compression can result in radicular pain. The back pain is often worse after lying down and this can be a vital clue. Rapidly developing weakness in the legs is the initial and dominant neurological symptom once malignant spinal cord compression occurs; sensory symptoms are less common and sphincter disturbance occurs late. A delay in the diagnosis of malignant cord compression is common with many patients only diagnosed after they lose their ability to walk [2, 3] and, unfortunately, once significant cord compression related to malignancy occurs the prognosis for recovery is poor.

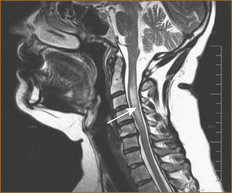

In patients with preexisting malignancy, particularly breast and prostate, the development of back pain should raise the suspicion of possible secondary malignancy in the spinal column and prompt investigation (see Figure 13.3).

The following suggest spinal metastases:

• pain in the thoracic or cervical spine

• severe unremitting or progressive lumbar spinal pain

• spinal pain aggravated by straining

• nocturnal spinal pain preventing sleep

It has been recommended that patients with known malignancy should be advised to return urgently within 24 hours for review should they develop back pain in the midline [4].

Severe thoracic back pain followed by the rapid development of spinal cord compression can be the initial manifestation of malignancy in as many as one-third of patients with cancer of unknown primary origin, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, myeloma and lung cancer [2]. Metastatic disease less commonly affects the cervical or lumbar spine. Although almost any systemic cancer can metastasise to the spinal column, prostate, breast and lung are the most common [2].

Intrinsic spinal cord problems: Transverse myelitis is the commonest intrinsic cord lesion resulting in dysfunction in the lower limbs and difficulty walking in the younger patient while spinal cord ischaemia is seen in the elderly. Spinal cord ischaemia can develope abruptly or insidiously. Other intrinsic spinal cord problems such as tumours and the cavitating lesion referred to as syringomyelia are very rare and are beyond the scope of this book.

TRANSVERSE MYELITIS: Acute transverse myelitis (ATM) is a focal inflammatory disorder of the spinal cord, resulting in motor, sensory and autonomic dysfunction with many infectious and non-infectious causes [10].

The Transverse Myelitis Consortium Working Group [11] has established diagnostic criteria that require:

• bilateral signs and/or symptoms of spinal cord dysfunction affecting the motor, sensory and autonomic systems

• a clearly defined sensory level

• the exclusion of cord compression

• the demonstration of inflammation within the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). If none of the inflammatory criteria is met at symptom onset, repeat MRI and lumbar puncture evaluation should be performed between 2 and 7 days following symptom onset.

The development of neurological symptoms and signs is often preceded by a febrile illness up to 4 weeks prior to onset [12], typically an upper respiratory tract infection. Patients present with an ascending sensory loss, with the development of a sensory level in the majority of patients with or without a paraparesis, paraplegia, quadriplegia and urinary retention [12, 13]. The symptoms may develop rapidly over as little as 4 hours or more slowly over several weeks.

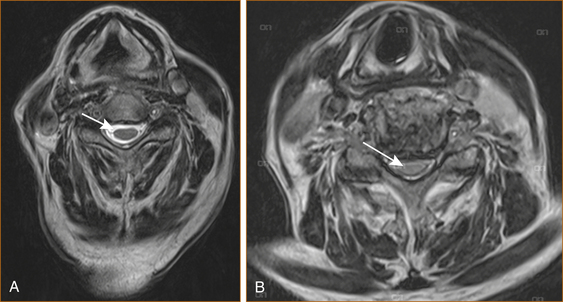

In one study of acute transverse myelitis, a parainfectious cause was diagnosed in 38% of patients but the underlying infectious agent was identified in a minority of patients. In 36% of patients the aetiology remained uncertain and in 22% it was the first manifestation of possible MS. The MRI scan (see Figure 13.4) was abnormal in 96% of cases (i.e. a normal MRI is rare but does not exclude a diagnosis) [12].

Acute non-compressive myelopathies can also be classified according to their aetiology [14]:

2. systemic disease (e.g. systemic lupus erythematosus [SLE], antiphospholipid syndrome, Sjögren’s syndrome

4. delayed radiation myelopathy

CONUS MEDULLARIS LESION: This chapter has discussed central nervous system causes of difficulty walking whereas the previous chapter discussed peripheral nervous system problems. There is one very rare syndrome that produces both upper and lower motor neuron signs in the lower limbs and this is a lesion at the level of the conus medullaris (the lower end of the spinal cord at the level of the 2nd lumbar vertebra) with or without the involvement of the cauda equina (the sheath of lumbosacral nerve that extends from the lower end of the spinal cord through the spinal canal exiting at the appropriate level and that looks like a horse’s tail, hence the name).

BRAINSTEM PROBLEMS CAUSING WEAKNESS IN THE LEG(S)

Weakness caused by brainstem problems is usually unilateral or bilateral weakness affecting the lower limbs with or without involvement of the upper limbs and, if above the mid pons, the face. It is the presence of symptoms and signs pointing to the brainstem (see Chapter 4, ‘The cranial nerves and understanding the brainstem’) that is the clue to the site of the pathology.

CEREBRAL HEMISPHERE PROBLEMS CAUSING WEAKNESS IN THE LEG(S)

Weakness related to cerebral hemisphere problems is almost invariably unilateral, although bilateral lower limb weakness can occur with involvement of the parafalcine region, typically with cerebral infarction in the distribution of the anterior cerebral artery. The presence of abulia (see Chapter 5, ‘The cerebral hemispheres and cerebellum’) is the clue that the lesion is affecting the distribution of the anterior cerebral artery.

Difficulty walking due to unsteadiness

UNSTEADINESS IN THE ABSENCE OF WEAKNESS OR DIZZINESS

Patients with marked impairment of proprioception in the lower limbs will be very unsteady on their feet, particularly in the dark and when they close their eyes, e.g. while having a shower or washing their hair. This is often referred to as a sensory ataxia. Vitamin B12 deficiency with subacute combined degeneration of the cord is probably the commonest cause now that syphilis has largely been eradicated. Very rarely, impairment of proprioception results from a dorsal root ganglionopathy or sensory neuronopathy. This occurs as a paraneoplastic phenomenon [15, 16], in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome [17] or pyridoxine abuse [18]. The sensory ganglionopathies are extremely rare and are mentioned here because the neurological problem may antedate the diagnosis of malignancy or indicate recurrence in a patient with known malignancy and should prompt a search for malignancy [16].

Truncal ataxia occurs with hypothyroidism [19] and alcoholism [20]. Patients with isolated truncal ataxia walk with a wide-based gait with little in the way of nystagmus or ataxia in the limbs.

The commonest cause of ataxia related to cerebellar disease would be cerebellar infarction. Two less common causes of cerebellar ataxia affecting the cerebellar hemispheres are the paraneoplastic cerebellar syndrome [21] and the hereditary spinocerebellar atrophies (SCA) [22]. The paraneoplastic cerebellar syndrome may be the initial presenting symptom of malignancy or develop after the diagnosis of malignancy is established. The clinical picture is one of very disabling ataxia affecting the limbs and trunk, together with dysarthria and nystagmus evolving rapidly over days to weeks. On the other hand, the hereditary spinocerebellar atrophies present with the insidious onset of ataxia affecting the limbs with or without nystagmus and dysarthria.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree