Katherine H. Noe

Joseph I. Sirven

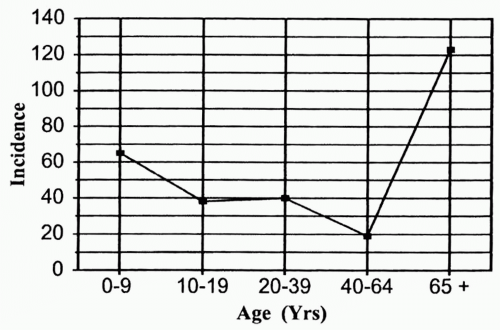

Epilepsy affects 1.5 to 3 million people of all ages in the United States annually. Although it is often mistakenly perceived as a childhood disorder, in fact, the most common time to develop seizures is after age 60. The prevalence of epilepsy in persons age 65 or older is twice that in young adults, and it continues to increase with age (Fig. 30-1) (27,28). Failure to recognize the increased prevalence of new-onset cases of epilepsy in the older adult may contribute to misdiagnoses. Furthermore, epilepsy in the elderly is distinct in its etiologies and presentation, which, along with increased medical comorbidity, adds to the difficulty in appropriate diagnosis and evaluation of seizures in the older adult compared to younger patients. Once recognized, the goals of seizure treatment in the elderly are the same as those for younger adults, namely to prevent future seizures and related injury and to maintain quality of life. In practice, however, epilepsy treatment in the older population presents unique challenges. Higher incidence of drug side effects, medication interactions, and altered pharmacokinetics are among areas of particular concern. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of evidence-based data regarding use of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in this group, and management of the older epilepsy patient is often based on information extrapolated from younger patients without consideration for the unique problems and issues associated with a geriatric population. This review will discuss issues of diagnosis and treatment of epilepsy unique to the older age group.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Seizures occur more frequently in the elderly, in part because they are often secondary to conditions more common in patients over age 60. These conditions include stroke, cerebral hemorrhage, tumor, and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s dementia. Therefore, to gain a clear understanding of the incidence of seizure disorders in this age group, distinctions must be made between acute symptomatic seizures and epilepsy. Acute symptomatic seizures are those directly attributable to or provoked by an acute insult to the central nervous system (CNS) or by a systemic metabolic derangement. In contrast, epilepsy is a condition of repeated unprovoked seizures and is diagnosed only when two or more such seizures have occurred. Epilepsy can occur without a clear underlying etiology (idiopathic epilepsy) or from a chronic CNS lesion such as encephalomalacia from old stroke (remote symptomatic epilepsy). The evaluation and management of each of these seizure presentations will be discussed.

ACUTE SEIZURES

Acute symptomatic seizures are not uncommon in the elderly. In a population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, the incidence was 82 per 100,000 person-years between the ages of 66 and 74, rising to 123 per 100,000 in those aged 75 or more (1). In elderly patients, about half of all acute symptomatic seizures are attributed to cerebrovascular disease (seizures occurring within 1 week of an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke) (1,19,62). Other frequently cited etiologies included toxic/metabolic derangements, trauma, neoplastic disease, and medication or alcohol withdrawal (1,14,26,55). Disordered serum glucose, including hypoglycemia associated with insulin use and nonketotic hyperglycemia, is often a cause of seizures in diabetics (40,57). Hyponatremia, uremia,

and hypocalcemia are also well represented in the literature (37). Abrupt discontinuation of sedative and anxiolytic drugs is a prominent cause of seizures in this age group. All barbiturates and benzodiazepines present a risk of withdrawal seizures (44,67,76). Many commonly prescribed medications can also lower seizure threshold. Drugs such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, theophylline, antibiotics such as newgeneration quinolones, and certain pain medications such as meperidine may lead to seizures (44,76). Overthe-counter herbal supplements such as ginkgo biloba may also have this effect (22,34). CNS infection is a relatively uncommon cause of acute seizures in the elderly patient in the United States but should be suspected in the setting of fever, meningeal signs, or immunosuppression. Acute symptomatic seizures are associated with increased 30-day mortality, with a case fatality in patients aged 65 or older of 30% to 40% (30). It is not yet known whether mortality reflects the severity of the underlying brain insult or an independent effect of seizure activity.

and hypocalcemia are also well represented in the literature (37). Abrupt discontinuation of sedative and anxiolytic drugs is a prominent cause of seizures in this age group. All barbiturates and benzodiazepines present a risk of withdrawal seizures (44,67,76). Many commonly prescribed medications can also lower seizure threshold. Drugs such as antipsychotics, antidepressants, theophylline, antibiotics such as newgeneration quinolones, and certain pain medications such as meperidine may lead to seizures (44,76). Overthe-counter herbal supplements such as ginkgo biloba may also have this effect (22,34). CNS infection is a relatively uncommon cause of acute seizures in the elderly patient in the United States but should be suspected in the setting of fever, meningeal signs, or immunosuppression. Acute symptomatic seizures are associated with increased 30-day mortality, with a case fatality in patients aged 65 or older of 30% to 40% (30). It is not yet known whether mortality reflects the severity of the underlying brain insult or an independent effect of seizure activity.

CHRONIC SEIZURES—EPILEPSY

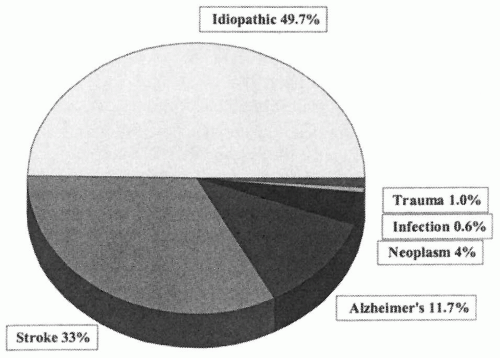

The number of epilepsy cases also rises steadily after age 60 (Fig. 30-1). The annual incidence of epilepsy is 134 per 100,000 in those aged 65 years or older (27,28,36,38,55,66). The prevalence of chronic seizures may be even higher in the institutionalized elderly, with studies reporting 10% of nursing home residents with documented seizure activity and/or receiving AED therapy (17,35). Epilepsy in this age group is commonly related to remote CNS insults or to chronic progressive neurologic disease. In a population-based study from Rochester, Minnesota, major etiologies were cerebrovascular disease (33%), dementia (11.7%), neoplasm (4%), infection (0.6%), and trauma (1%) (Fig. 30-2) (26). In the remaining half of the patients, no definitive cause was identified (26). Similarly, in a Veterans Administration study of newly diagnosed epilepsy in patients aged 60 years and above, the most common etiology was stroke (43%), followed by arteriosclerosis (16%), unknown etiology (24%), and head trauma (7%) (54). The majority of older adults experience partial seizures, as would be predicted by the presence of underlying acquired etiologies. In persons with epilepsy aged 65 years or greater, 13% have simple partial seizures, 49% have complex partial seizures, and 29% have generalized or myoclonic seizures (27). This is in contrast with children, in whom the most prevalent seizure types are generalized (50%), with 11% having simple partial and 23% having complex partial events.

STATUS EPILEPTICUS

Status epilepticus (SE), which is defined as >30 minutes of continuous seizure activity or of intermittent seizures without return to consciousness, is also more common in older adults. The incidence of SE in the elderly is two to five times higher than in young adults (11,70). SE occurs not only in the setting of known seizure disorder, but it can also be the first presentation of epilepsy or a result of acute symptomatic derangements. In fact, 30% of all acute symptomatic seizures in older people present as SE (7). The elderly are not only more likely to develop SE, but are also more likely to die as a result. In a database of SE cases from Richmond, Virginia, the mortality rate for all adults was 26%, increasing to 38% after age 60 and to 50% after age 80 (11,12). Forty percent of SE cases in elderly are attributable to acute or chronic stroke (71). Although acute stroke is likely to contribute significantly to overall morbidity and mortality in these cases, the mortality of stroke with SE is three times greater than that seen with stroke alone (72). SE following anoxic brain injuries, such as is often seen after cardiopulmonary arrest, has a mortality rate close to 100% (71).

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

One obstacle in the treatment of epilepsy in older adults is misdiagnosis. In a Veterans Administration study of new-onset epilepsy in elderly patients, seizure disorder was not seriously considered as a diagnosis at first evaluation in one fourth of the cases (52). Common misdiagnoses were syncope/blackout (46%), altered mental status (42%), and dementia (7%). Although it is relatively easy to recognize a classic generalized tonic-clonic seizure, older adults are more likely to experience partial seizures with clinical manifestations unique from those often seen in younger patients. One suggested reason is that the epileptic focus in older adults involves the frontal and parietal lobes rather than the temporal lobe (51). Thus, these patients are less likely to experience auras such as déjà vu and other symptoms classically associated with

temporal lobe epilepsy. Rather, these patients will complain of dizziness, posturing, paresthesias, and other symptoms related to frontal and parietal lobe function. Further confusion may arise in the elderly due to the increased presence of multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, and, in some instances, difficulty obtaining the history due to underlying cognitive impairment. Lastly, the postictal period may last for days in the older adults, mimicking a delirium or dementia and further contributing to the difficulty in diagnosis.

temporal lobe epilepsy. Rather, these patients will complain of dizziness, posturing, paresthesias, and other symptoms related to frontal and parietal lobe function. Further confusion may arise in the elderly due to the increased presence of multiple comorbidities, polypharmacy, and, in some instances, difficulty obtaining the history due to underlying cognitive impairment. Lastly, the postictal period may last for days in the older adults, mimicking a delirium or dementia and further contributing to the difficulty in diagnosis.

Diagnosis requires a detailed and accurate history. Patients are often unaware of what has occurred, so obtaining an eyewitness account is invaluable. Syncope, transient ischemic attacks, transient global amnesia, and vertigo are common conditions at this age and can present similarly to seizures (68). Table 30-1 lists common discriminators of these events and seizures. Although these variables may be helpful, they remain nonspecific. Carefully detailed questions about the episodes and about epilepsy risk factors, including minor or major head trauma and concomitant medications, must be asked.

Further diagnostic testing is often needed to confirm or clarify the etiology of a seizure-like spell. Depending on the history evaluation of metabolic derangements, cardiac disease, cerebrovascular disorders, or vestibular dysfunction may be considered as appropriate. For epilepsy evaluation, electroencephalography (EEG) and neuroimaging are standard tests, the value and limitations of which are discussed further in the following sections.

ELECTROENCEPHALOGRAM

EEG is a cornerstone of seizure evaluation in all age groups. However, elderly patients are more likely to have nonspecific or nonepilepsy-related EEG changes, which can add to diagnostic errors in the unwary. Findings related to normal aging may include mild slowing or decreased amplitude of the background rhythms or intermittent slowing over the temporal head regions (33,46). EEG in this age group may also show benign patterns that are misinterpreted as epileptogenic by the inexperienced reader, such as small sharp spikes, wicket spikes, or subclinical rhythmic electrical discharges of adulthood (SREDA), the latter occurring exclusively in older adults (33,53, 56,73,74). To add to possible diagnostic confusion, truly epileptogenic findings, such as spikes or sharp waves, appear less commonly in the EEGs of elderly individuals with epilepsy than in those of young patients. Only 26% to 37% of older patients with epilepsy demonstrated epileptiform abnormalities on routine EEG (13,51). Thus, the absence of epileptiform abnormalities on an EEG should not exclude the diagnosis of seizures or epilepsy. When epileptogenic discharges are present, they are strongly suggestive of a seizure diagnosis; however, even this finding must be interpreted cautiously with the clinical history in mind. Epileptiform transients may be seen in patients with diseases other than epilepsy, such as dementia, stroke, neoplasms, and prion diseases (9,13,45). The “gold standard” of epilepsy diagnosis with EEG is the actual recording of a seizure. Therefore, when the diagnosis of seizures or epilepsy remains in question, prolonged inpatient video-EEG or ambulatory EEG monitoring should be strongly considered.

Table 30-1. Variables That Distinguish between Common Spells in the Elderly | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree