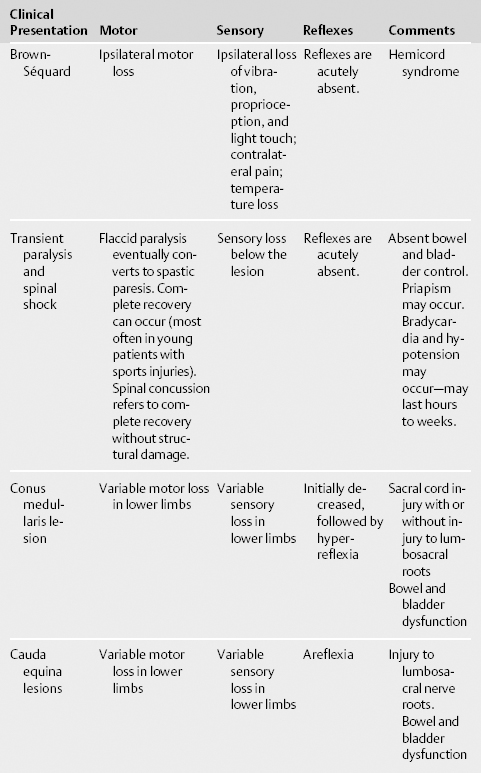

8 Acute Spinal Cord Injury Scott Meyer, Jennifer A. Frontera, Arthur Jenkins III, and Tanvir Choudhri Spinal cord injuries (SCIs) inflict a significant burden on patients, families, and society as a whole. The spinal cord consists of 31 segments and terminates near L1 (T10-L3) in adults. Most injuries involve not only the cord, but exiting nerves as well. SCI is most common in the young (average age 29 years) and in men (78%).1 The most common causes of SCI are motor vehicle accidents (MVAs; 47%), falls (23%), violence (14%), sporting accidents (9%), and other causes (7%).1 Alcohol plays a role in up to 25% of SCI and underlying spinal disease such as cervical spondylosis, atlantoaxial instability, osteoporosis, and spinal arthropathies can make patients more prone to SCI. Roughly half of all SCIs involve the cervical cord. SCI can be divided into two separate mechanisms of action: primary and secondary SCI. Primary SCI occurs as a result of pathologic flexion, rotation, extension, compression, contusion, or shearing of the spinal cord. This can be caused by a fracture-dislocation, tearing of ligaments, or disruption and/or herniation of the intervertebral disks. Kinetic injury transmitted from bullet wounds or blasts can cause cord injury even when no foreign body has entered the spinal column. The primary SCI is irreversible, and prevention of the initial injury is the primary modifiable feature. Secondary SCI is a complex chain of events linked to ischemia, hypoxia, edema, excitotoxicity, and inflammation with changes on the cellular level. Aims of intervention and management are to limit the effects of secondary injury processes as well as prevent associated medical morbidities. See Table 8.1 for the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) Scaleand Table 8.2 for examination findings in different types of SCI.

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

| Category | Description |

| A | Complete: No motor or sensory function is preserved below the neurologic level through sacral segments S4-S5. |

| B | Incomplete: Sensory but not motor function is preserved below the neurologic level and includes S4-S5. |

| C | Incomplete: Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and more than half of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade <3. |

| D | Incomplete: Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and at least half of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade ≥3. |

| E | Motor and sensory functions are normal. |

Data from: Clinical assessment after acute cervical spinal cord injury. Neurosurgery 2002; 50(3, Suppl)S21-S29.

Differential Diagnosis

Acute Presentation

- Spinal cord trauma

- Fracture of bony elements with cord or nerve injury

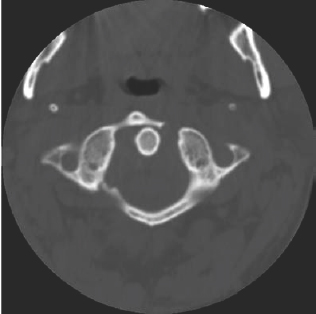

- Jefferson fracture (Fig. 8.1): Typically a four-part fracture of the atlas (C1), with bilateral fractures to the anterior and posterior arches, usually from axial load compression (such as from a diving injury)

- Hangman’s fracture (traumatic spondylolisthesis) (Fig. 8.2): Bilateral pars fracture of axis (C2) vertebral body with various degrees of anterior subluxation and disruption of the C2/3 disk space, usually due to extension trauma from an MVA or hanging

- Jefferson fracture (Fig. 8.1): Typically a four-part fracture of the atlas (C1), with bilateral fractures to the anterior and posterior arches, usually from axial load compression (such as from a diving injury)

- Ligamentous injury (injury causing subluxation may only be seen on dynamic studies such as flexion-extension plain films or magnetic resonance imaging [MRI])

- Herniation of intervertebral disk

- Penetrating injury (bullet, knife wound, etc.)

- Kinetic injury (blast or nearby bullet wound)

- Spinal cord injury without radiographic abnormality (SCIWORA): More common in children; may be due to longitudinal distraction or transient ligamentous deformation with spontaneous reduction

- Kinetic injury (blast or nearby bullet wound)

- Fracture of bony elements with cord or nerve injury

- Vascular. The blood supply to the cord consists of one anterior and two posterior arteries.

- Carotid/vertebral dissection can occur in the setting of trauma or bony fracture. Consider arterial imaging with CT angiogram, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or digital subtraction angiography.

- Spinal cord infarction can be due to vessel disruption, emboli, or hypoperfusion. T4-T8 represents the watershed territory between the anterior spinal artery and the artery of Adamkiewicz originating at T9. At any particular level, the central part of the cord is the watershed area. Cervical hyperextension injuries can cause ischemia, resulting in central cord syndrome. Minor vascular supply comes from branches of the vertebral artery and thyrocervical trunk as well, so injury to these structures may lead to ischemia.

- Vascular malformations

- Epidural hematoma

- Carotid/vertebral dissection can occur in the setting of trauma or bony fracture. Consider arterial imaging with CT angiogram, magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), or digital subtraction angiography.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree