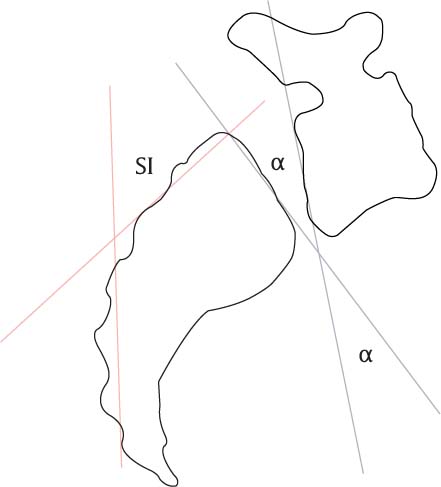

18 Spondylolisthesis a common spinal condition in adolescents and adults defined as the slippage or displacement forward of one vertebra on the spinal segment below. The underlying pathology leading to the slip may vary but the clinical presentation can be quite similar. The patient often presents with severe back and leg pain, and there may be cosmetic or postural concerns. Cauda equina symptoms are possible but uncommon. The vast majority of patients with spon-dylolisthesis are of the lower grades (less than 50%), with only a small percentage of slips progressing into the category of high-grade spondylolisthesis.1 Secondary to the relatively early manifestation of symptoms, patients tend to seek medical advice and often surgical treatment prior to adulthood. As mentioned by previous authors in this text, the percentage of slippage may be calculated by measuring the distance between the posterior borders of the vertebral elements, commonly L5 and S1, at the superior end plate, divided by the sagittal length of the inferior vertebral end plate. Meyerding further classified the degree of spondylolisthesis based on the percentage of slippage and graded the spon-dylolistheses I through IV.2 Most authors agree by definition that grades III and IV are considered high grade and are generally associated with a higher incidence of slip progression and disabling symptomatology. High-grade slips at the lumbosacral junction are more involved than simply anterior translation of a vertebral segment. When the L5 vertebra reaches a certain threshold of translation, it often rotates into flexion forming kyphosis at the lumbosacral spine. When the L5 vertebra completely slips, tilts, or dislocates over the sacrum it is a condition called spondyloptosis and can be quite disabling and disfiguring. Just as the anterior displacement of one vertebral element can be evaluated by different techniques by different authors, the angular relationship of one vertebral body to another imparts much clinical significance and influences surgical decision making. Various terminology has been utilized in the literature to describe this angular relationship, including lumbosacral kyphosis or angle of kyphosis, but most commonly it is referred to as the slip angle. The slip angle, when positive, measures lumbosacral kyphosis and may have a profound impact on the entire lumbar spine because the patient often compensates with hyperlordosis, leading to facet joint changes, stenosis, and potential retrolisthesis proximal to the more obvious deformity at L5–S1 (Fig. 18.1). This chapter’s focus is the surgical treatment of adult high-grade spondylolisthesis using the best evidence available. Fair mention must be given to the classification system of Wiltse, Newman, and Macnab3 and the more recent classification scheme of Marchetti and Bartolozzi,4 both of which aid our understanding of spondylolisthesis and guide the surgeon in the understanding of treatment options. The Wiltse-Newman-Macnab classification of initially five categories eventually expanded into six to include iatrogenic spondylolisthesis. Type I is based on a congenital or dysplastic problem of the lumbosacral junction, which permits slippage of L5 on the sacrum. Type II spondylolisthesis is a failure, whether it is a fracture or an elongation of the pars interarticularis, leading to the loss of sagittal alignment termed isthmic spondylolisthesis. Degenerative spondylolisthesis is type III in the Wiltse classification scheme, which is more of a long-standing failure of the spinal segment, including the facet joints and disk structures, that allows forward slipping of a vertebral body. Type IV spondylolisthesis is from a traumatic event and injury to the posterior structures allowing for forward slippage of a vertebral segment. Type V spon-dylolisthesis is considered pathological in that the slippage is a result of local or systemic destructive bone pathology. Lastly with spinal decompression surgery supporting structures can be disrupted or weakened leading to postsurgical or iatrogenic spondylolisthesis, or type VI in this classification scheme. Fig. 18.1 Schematic representation of the slip angle. α, slip angle; SI, sacral inclination. The management of adult spondylolisthesis, like other spinal pathologies, remains controversial. The pain and disability associated with high-grade slips are significant; the natural history is concerning and often involves surgical intervention. The adult population presents the clinician and surgeon with different clinical challenges. There are a limited number of high-grade studies to aid the surgeon in decision making. Nevertheless, there are still numerous articles discussing high-grade lumbar listhesis in adults to enable the surgeon to make sound surgical decisions. The role of reduction of adult high-grade spondylolisthesis versus fusion of the deformity in situ remains controversial. The number of adults impaired with this condition remains relatively small; thus there are few studies published. A comprehensive literature review revealed 3649 citations to date in PubMed for the general topic of spondylolisthesis, of which only 119 articles pertained to adult high-grade spondylolisthesis. A combination of adult high-grade spondylolisthesis and surgical treatment resulted in three published articles. A further review of the references of these articles was performed for any additional literature. For various legitimate reasons, there are no randomized, controlled clinical trials on this topic nor are there any prospective series for evaluation. Therefore, level I and level II studies are not found in the literature. The best available evidence to guide the surgeon is in the form of level III data or retrospective series reviews, of which there are several outstanding contributions in the literature. A spondylolisthesis summary statement through the Scoliosis Research Society was published in 2005 and will be discussed later in this chapter. There are no level I studies on this topic. There are no level II studies on this topic. Although this chapter concerns adults with high-grade slips, insight can certainly be gained from some of the pediatric literature that directly compares the effects of reduction and fusion versus fusion in situ for the high-grade dilemma.5–9 General recommendations for reductions of high-grade spondylolisthesis include major sagittal imbalance, severe stenosis, substantial radiculopathy, or neurological deficit.10 Much of the retrospective evidence has combined age groups from children, adolescents, and young adults. When the surgeon is faced with middle-aged or more senior adults, those with high-grade spondylolisthesis often have had prior lumbar surgery, and one must consider comorbidities such as osteoporosis, degeneration at other levels, coronal imbalance, along with general medical concerns. Transfeldt and Mehbod performed an evidence-based analysis of isthmic spondylolisthesis treatment including reduction and fusion versus fusion in situ for high-grade slips in children.11 The authors were able to find only five high-quality level III studies for their analysis. The authors concluded that there is no clinically significant difference in outcomes of patients treated with in situ fusion versus reduction and fusion. The adult literature is limited and again consists of retrospective reviews. An additional shortcoming is that most published adult studies are actually a merger of both pediatric and adult patient groups with no distinction between surgical care or clinical outcomes. Furthermore, these studies illustrate the continued evolution of thinking and technology over time as the surgeons modify their techniques within their own learning curve. A landmark article was written by Smith and Bohlman in 1990.12 The authors reported on an innovative surgical technique for stabilization of high-grade spondylolisthesis. They reported on 11 skeletally mature (ages 14 to 54 years) patients that underwent decompression and in situ posterolateral and anterior uninstrumented fusion. All patients had grade III to V deformities and had fibular strut autograft and autologous iliac crest posterolateral bone grafting as part of the index procedure. After a wide laminectomy of the fourth and fifth lumbar and first sacral segment, a fibular autograft was inserted from the sacrum into the vertebral body of L5 anteriorly. No instrumentation or correction of the deformity was performed. The follow-up period ranged from 2 to 12 years; all patients were found to achieve a solid fusion and there were no neurological complications from the procedure. Four patients had temporary loss of bladder function as part of a cauda equina syndrome and regained function postoperatively. The authors concluded that reduction of a high-grade spondylolisthesis is not needed, and good results can be achieved with a noninstrumented fusion. Limitations of the study include the small number of patients treated by this novel technique and also the lack of a comparative cohort. The technique of combined reduction and stabilization was described by Bradford in 1979.13 In 1990, a follow-up study by Bradford and Boachie-Adjei on the same technique was reported.14 Nineteen patients (age 13 to 30 years) with grade IV and V spondylolisthesis underwent anterior and posterior reduction and stabilization. The surgical technique included a posterior decompression, removal of the loose posterior arch of L5, complete diskectomy of the L5/S1 disk, sacral dome osteotomy, and noninstrumented arthrodesis from the transverse process of L4 to the sacrum. Reduction was gradually achieved with halo-femoral or halo-pelvic traction. Postoperatively, there were two L5 nerve motor neuropraxias and one cauda equina syndrome that responded to exploration and decompression. Four patients developed a pseudarthrosis that required reoperation. Slip angle improved from an average of 71 degrees to 28 degrees at follow-up. Sagittal plane alignment was restored in 89% of the patients. All but one patient had resolution of back pain and radiculopathy. The authors concluded that this technique can be performed safely and produces good clinical results. Although the authors have reported desirable outcomes in this cohort, some may argue that a reoperation rate of one in four may be excessive. Peek et al15 reported on eight adults who had in situ arthrodesis without decompression for grades III through V isthmic spondylolisthesis. All patients had severe sciatica and neurological findings. After a Wiltse approach was performed, the bony elements within the spinal fusion levels were exposed and decorticated. Arthrodesis levels were selected based on their relationship to the sacrohorizontal angle. Patients underwent a noninstrumented fusion anywhere from L3, L4, or L5 to S1. No instrumentation or postoperative bracing was used. All patients achieved a solid fusion by 6 months, and there was no evidence of deformity progression. The radiculopathy resolved in all patients, and all patients reported excellent clinical results. The authors concluded that noninstrumented in situ fusion for high-grade spondylolisthesis is safe, effective, and avoids the potential complications associated with instrumentation and reduction techniques. DeWald et al16 reported on a retrospective series of 21 adults (ages 21 to 68 years) that were surgically treated for high-grade spondylolisthesis. Twenty patients underwent fusion with instrumentation. Sixteen patients had a reduction of their listhesis as a part of their surgical treatment: two near-complete and 14 partial reductions. All but one patient received interbody strut support via an anterior or a posterior approach. Postoperatively, nine patients (45%) developed a neurological deficit; two of which had been fused in situ. Most of these deficits were only temporary in nature. There was one case of progression of an incomplete cauda equina syndrome that became permanent and a single case of instrumentation failure at the S1 screws. No pseudarthroses were noted. At final follow-up, there were 12 excellent, seven good, one fair, and one poor clinical outcome. The authors concluded that performing a partial reduction is a viable option when performing an instrumented fusion for high-grade spondylolisthesis. The use of adjunctive fixation such as iliac screws or bolts was recommended. A criticism of this study was that it has a low number of patients. Fusion levels, percent reduction, and interbody strut placement varied greatly in this cohort of patients. Also, more detailed and standardized outcome instruments would have been desired for reporting the clinical outcomes. Ruf et al17 reported on anatomical reduction and monoseg-mental fusion in high-grade developmental spondylolisthesis in 27 consecutive patients. The mean age of patients was 16 years (range 9 to 28). All patients presented with back pain, and 13 had a radiculopathy. One patient had an early cauda equina syndrome. The authors described a surgical technique in which operative reduction of the L5 vertebra was achieved by temporary distraction between L4 and the sacrum. Following diskectomy, Harms cages were inserted, and the L5–S1 instrumentation was locked in place. Clinical results revealed that 23 patients were pain free, and four had moderate pain at the latest follow-up. Five patients had a transient L5 radiculitis, and one patient had a permanent L5 sensory deficit. All radiographic parameters were significantly improved, including mean slippage, slip angle, sacral inclination, and sagittal balance. The main conclusions of this study were as follows: temporary L4 instrumentation allows for reduction of a listhetic L5 vertebra, complete reduction is possible with a reasonable risk of neurological complications, the L4–L5 segment can be preserved without compromising the adjacent operative level. This study highlights the usefulness of temporary distraction as a means to achieve reduction of the lumbosacral slippage. Preservation of motion of an otherwise healthy L4–L5 segment is key in young patients to help retain motion in the lumbar spine. A criticism of this study is the lack of a detailed age distribution as well as grouping very young children and adults in the same cohort. Sailhan et al18 retrospectively reviewed 44 patients that had undergone an instrumented reduction and fusion without decompression for high-grade spondylolisthesis. The cohort included adult (> 18 years, 22/44) and pediatric (< 18 years, 22/44) patients. Two patients underwent isolated anterior surgery without reduction. All other patients had a posterior instrumented reduction and fusion; 21 had supplemental anterior interbody fusion. No decompression of neural elements was performed. Reduction from an average of 64% slippage preoperatively to 38% postoperatively was achieved. There were five cases of pseudarthrosis, four of which had been treated with a combined anterior-posterior approach. Postoperative neurological deficits involving the L5 nerve root were found in five patients (9.1%), two of which were permanent. Four out of the five patients with neurological involvement had been treated with a combined approach. At the last follow-up, 90% of the patients had a good or fair outcome. The authors concluded that a reduction of ~50% of the preoperative displacement can be accomplished safely without decompression of the nerve roots. Limitations of this study included the conglomeration of adult and pediatric patients. There was a relatively high rate of pseudarthrosis and neurological deficits in patients that underwent combined anterior and posterior fusion. Smith et al19 reported on nine consecutive patients (four adults, five children) with high-grade spondylolisthesis. The surgical treatment consisted of a decompression of neural elements, partial reduction of the listhetic vertebra, transsacral interbody fusion followed by an instrumented fusion. Their indications for partial reduction were sagittal imbalance of 5 cm or more, significant cosmetic deformity related to lumbosacral kyphosis, or both. Seven of the nine patients underwent reduction. Radiologically, there was a great improvement in the slip angle, lumbosacral kyphosis, sacral inclination, and percent slippage. Major complications included a case of diffuse intravascular coagulopathy and two cases of transient L5 motor neuropraxia. Evaluation by the Scoliosis Research Society (SRS) outcomes instrument revealed that all patients were either extremely or somewhat satisfied with the operation results. Major limitations of this study included the low number of patients enrolled and the combination of adults and pediatric patients in the same cohort. Otherwise, they were able to conclude that good clinical and radiological results can be achieved with a partial reduction and transsacral interbody fusion with pedicle screw instrumentation in patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis. Bartolozzi et al20 reported on 15 patients that underwent one-stage posterior decompression-stabilization and transsacral interbody fusion after partial reduction for severe L5–S1 spondylolisthesis. The authors performed a surgical technique previously described by Bohlman and Cook.21 However, instead of utilizing a fibular autograft, they used a transsacral titanium cage to stabilize the listhetic segment as well as pedicular fixation. Twelve patients were adults (age range 11 to 37 years), most patients had fusions from L4 to S1, and in two the arthrodesis extended to L5 only. Correction of the deformity and slippage was achieved by a temporary distraction with Harrington rods between L2 and sacral alae. There was one major intraoperative complication due to a lesion of the left iliac vein during preparation for the pedicle screw. Only one patient had a partial motor deficit, but otherwise there were no implant failures or pseudarthrosis at final follow-up. The SRS outcome instrument revealed that all patients but one were extremely or reasonably satisfied with the results of the surgery. Radiographic parameters improved significantly: mean percent slippage from 69.3% to 55.8%, slip angle from 31 degrees to 21 degrees, and sacral inclination from 33.8 degrees to 45.9 degrees at final follow-up. The authors concluded that this technique yielded satisfactory radiological and clinical outcomes. One of the few limitations of this article was the small number of adult patients enrolled. Otherwise they have encouraging results favoring a partial reduction, circumferential fusion, and pedicular stabilization. Boos et al22 also reported on partial reduction and pedicular fixation in a cohort of 10 patients with spondylolisthesis and spondyloptosis. They used first-generation internal fixation systems and Cotrel-Dubousset instrumentation. All four patients with spondyloptosis were treated by a combined posterolateral and interbody fusion. Five of six patients that underwent an isolated posterolateral fusion developed loss of reduction, pseudarthrosis, and implant failure. Four of these required revision surgery. Eventually, however, all patients had resolution of their symptoms. The authors concluded that posterolateral fusions using pedicular fixation systems should be used only in conjunction with an interbody arthrodesis due to the high failure rate they observed. Limitations of this study included a low number of patients with a relatively high percentage of spondyloptosis (40%). Some authors may argue that the treatment for the latter may be more complex and involved than for simpler high-grade slips and may include a complete vertebrectomy, otherwise known as a Gaines procedure. Additionally, one can argue that using modern instrumentation systems may have resulted in improved fusion rates. There are no prospective, randomized studies that compare the effects and clinical outcomes of reduction and arthrodesis versus in situ fusion for adult patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis. Only a limited number of level III evidence studies exist that report on short- and long-term outcome of patients undergoing these procedures. The best evidence available suggests that both reduction and in situ fusion can be performed safely and provide reliable radiological and clinical outcomes in terms of fusion success and pain improvement. There is a comparable rate of adverse outcomes and risks that occur with both procedures. The vast majority of neurological deficits that occur with these surgeries are only transient in nature. Other complications such as pseudarthrosis, instrumentation failure, and need for reoperation are also seen with both techniques. Although there are no studies specifically analyzing the results and outcomes strictly based on the amount of reduction, most proponents of this technique recommend only a partial reduction. Radiological parameters such as slip angle, percent slippage, lumbosacral kyphosis, and sacral inclination can be improved significantly with reduction of the deformity. However, there are no data suggesting that improvement of the foregoing factors translates to a better clinical outcome. A summary statement for spondylolisthesis was written by the Spine/Scoliosis Research Society.23 The importance of global sagittal plane alignment is highlighted in this article. Patients with high-grade developmental spondylolisthesis may benefit from having a reduction of the deformity to improve global spinal balance and perhaps enhance the biomechanical environment for fusion. Strong consideration for reduction should be given to pediatric patients, particularly those with significant lumbosacral kyphosis. However, whether or not listhesis reduction is performed should be individualized to each patient. Further research is needed to identify patients at risk of spondylolisthesis progression and spondylolysis development. A more comprehensive classification system that takes into consideration the etiology, radiographic parameters, and clinical manifestations, and that guides the surgeon in treatment decisions is greatly desired. After a thorough review of the literature, it seems that both reduction and arthrodesis and in situ fusion are safe procedures that result in satisfactory clinical outcomes for adult patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis. Both surgeries have reasonable complication rates and a similar adverse event profile. However, data are not sufficient to show significant clinical superiority of one procedure over another. Global spinal balance and other radiological parameters can be improved by performing a reduction of the listhetic segment. A partial reduction of the listhesis may be considered in younger patients that have a significant clinical deformity. Pearls A prudent and safe approach of adult patients with high-grade spondylolisthesis includes the following: • Decompression of the neural elements, both central and foraminal • Partial reduction of the slip • Stabilization and posterolateral fusion of the segment with modern pedicle instrumentation of the listhetic segment at a minimum • Interbody support via anterior, posterior, or transsacral approach

Adult High-Grade Spondylolisthesis: Role of Reduction versus Fusion In Situ

Summary of Literature Review

Summary of Literature Review

Discussion of Evidence

Discussion of Evidence

Level I Data

Level II Data

Level III Data

Summary of Data

Summary of Data

Review of Summary Statement

Review of Summary Statement

Conclusions

Conclusions

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree