CHAPTER 28

Adult Psychiatry

I. Psychochemistry

A. Neurotransmitters

1. Dopamine (DA)

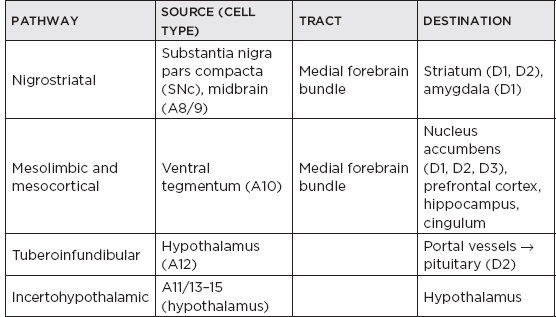

a. Dopaminergic pathways

b. Synthesis

i. Tyrosine—(tyrosine hydroxylase) → L-dopa—(dopa decarboxylase) → DA

ii. Tyrosine hydroxylase is the rate-limiting enzyme

c. Catabolism

i. DA is broken down by monoamine oxidase types A and B (MAOA, B) and catechol-O-methyl-transferase.

ii. End products are homovanillic acid and 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid.

d. Receptor “families” and their distributions

i. D1 family: characteristics—postsynaptic, excitatory; locations: D1—striatum, accumbens, olfactory tubercle, cortex, amygdala; D5—hippocampus, dentate gyrus, thalamus (parafascicular), cortex

ii. D2 family: characteristics—postsynaptic and presynaptic, inhibitory; locations: D2—striatum, accumbens, olfactory tubercle, lateral septum, SNc, ventral tegmentum, olfactory bulb, zona incerta; D3—olfactory tubercle, accumbens; D4—cortex (prefrontal and temporal), dentate gyrus, hippocampus

iii. Psychiatric significance: DA’s normal functions include movement, perception, motivation, reward, aggression; DA excess or hypersensitivity is associated with positive symptoms of schizophrenia (mesolimbic tract), and tardive dyskinesia (TD) (nigrostriatal tract); DA deficiency or blockade is associated with: extrapyramidal syndromes ([EPSs] striatum, nucleus accumbens), hyperprolactinemia (tuberoinfundibular), negative symptoms of schizophrenia, depression.

2. Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine [5-HT]): 5-HT is produced in the dorsal and median raphe nuclei—periaqueductal gray matter of midbrain and pons, B1–9 type cells; raphe neurons project through the medial forebrain bundle to hippocampus, hypothalamus, frontal cortex, striatum, and thalamus; receptors are also located on platelets (increase cohesion), sexual organs, and in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract (increase peristalsis).

a. Synthesis: tryptophan—[tryptophan hydroxylase] → 5-hydroxytryptophan—[5-HTPdecarboxylase] → 5-HT

b. Catabolism: 5-HT—[MAOA] → 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA)

c. Psychiatric significance

i. Normal functions of 5-HT include mood and sleep regulation, appetite, and impulse control.

ii. Stimulation of 5-HT1 receptors is associated with antidepressant activity.

iii. Stimulation of 5HT1D autoreceptors is associated with migraine treatment (“triptans”).

iv. Stimulation of 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptors is associated with psychosis.

v. Blockade of 5-HT3 receptors is associated with antiemetics (ondansetron).

vi. Decreased levels of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid are found in cerebrospinal fluid of violent and suicidal subjects.

vii. Peripheral 5-HT receptors cause antidepressants side effects (GI distress, sexual dysfunction).

![]() NB:

NB:

Low levels of CSF 5-HIAA have been reported among patients who have attempted suicide via violent means and in alcoholics with impulsive violent behavior. Norepinephrine and Catechol-O-methyl-transferase (COMT) have also been implicated.

3. Norepinephrine (NE): produced by cells in locus ceruleus; widely distributed targets (cortex, limbic system, thalamus, hypothalamus, reticular formation, dorsal raphe, cerebellum, brain stem, spinal cord)

a. Synthesis

i. Tyrosine—[tyrosine hydroxylase] → L-dopa (rate-limiting step)

ii. L-Dopa—[dopa decarboxylase] → DA—[dopamine β-hydroxylase] → L-NE

b. Catabolism is by MAOA and catechol-O-methyl-transferase to 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol

c. Psychiatric significance

i. Normal functions include focused attention, stress response, and aggression.

ii. NE reuptake inhibition is associated with treatment of depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

iii. Peripheral blockade leads to orthostatic hypotension (common side effect of psychiatric drugs).

4. Other neurotransmitters

a. γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA): GABA is a widely distributed inhibitory amino acid neurotransmitter; synthesis: glutamate—[glutamate decarboxylase] → GABA; GABA agonists are prescribed for anxiety, ethanol (ETOH) withdrawal, seizures, catatonia, and akathisia.

b. Acetylcholine (ACh)

i. Synthesis: Choline + acetyl coenzyme A—[choline acetyltransferase] → ACh

ii. Catabolism: ACh—[acetylcholinesterase] → choline + acetate

iii. Psychiatric significance: ACh is heavily involved in cognition and motor function; degeneration of ACh-ergic neurons is associated with cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s and other degenerative dementias; acetylcholinesterase inhibitors are prescribed to treat Alzheimer’s disease; anticholinergics should be avoided in the elderly and demented.

![]() NB:

NB:

Alzheimer’s disease presents with a decrease of choline acetyltransferase in the basalis nucleus of Meynert.

iv. Central ACh receptor blockade: used to treat EPSs caused by antipsychotics; used to treat parkinsonism; may cause disturbed cognition (particularly in elderly)

v. Peripheral ACh receptor blockade is responsible for side effects of many psychiatric medications; decreased visceral activity: dry mouth, constipation, urinary retention; parasympathetic: blurred vision, tachycardia.

![]() NB:

NB:

ACh, vital to encoding new memories, is one of the many neurotransmitters deficient in Alzheimer’s disease. Medications, including tricyclic antidepressants, antihistamines, and anti-emetics, with strong anticholinergic properties can worsen memory and cause confusion.

c. Glutamate: excitatory amino acid neurotransmitter; NB: normal activity associated with memory (N-methyl-D-aspartate [NMDA] receptor); antagonism associated with psychosis; NB: hyperactivity associated with excitotoxicity

d. Histamine (H): excitatory monoamine neurotransmitter; blockade causes drowsiness, weight gain, cognitive slowing.

B. Antidepressants: all antidepressants increase monoamine-dependent neurotransmission, most commonly in serotonergic systems; reuptake inhibition at the synapse increases monoamine activity; newer agents are generally more selective and less dangerous in overdose, black-box warning: antidepressants increase the risk of suicidal thinking and behavior in children, adolescents, and young adults (18–24 years of age) with major depressive disorder and other psychiatric disorders.

1. Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs): major indications: depression, migraine prophylaxis, neuropathic pain, anxiety disorders

a. Tertiary amines

i. 5-HT > NE reuptake inhibition

ii. More antihistaminic and anticholinergic activity than the secondary amines

iii. Examples: amitriptyline (Elavil®), clomipramine (Anafranil®), imipramine (Tofranil®), doxepin (Sinequan®)

![]() NB:

NB:

More sedating than other secondary amine classes.

b. Secondary amines

i. Secondary amine TCAs are derived from metabolism of tertiary amines.

ii. Amitriptyline → nortriptyline

iii. Imipramine → desipramine

iv. NE >> 5-HT reuptake inhibition

v. Examples: nortriptyline (Pamelor®), desipramine (Norpramin®), protriptyline (Vivactil®)

c. Tetracyclic: these are the only TCAs with some antipsychotic activity; examples: amoxapine (Asendin®), maprotiline (Ludiomil®).

d. Common side effects of TCAs

i. Potentially lethal in overdose

ii. Anticholinergic side effects include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, urinary retention, delirium, and memory impairment.

iii. Antiadrenergic (α1) activity causes orthostatic hypotension.

iv. Anti-H1 activity causes sedation and weight gain.

v. Cardiac toxicity in overdose (QT prolongation → torsades de pointes)

2. MAO inhibitors (MAOIs): examples: phenelzine (Nardil®), tranylcypromine (Parnate®); work through irreversible inhibition of MAOA, B; resynthesis of the enzymes takes 2 weeks.

a. Major uses: depression, migraine prophylaxis, borderline personality disorder, anxiety disorders

b. Side effects: potentially lethal in overdose; hypertensive crisis: sudden headache, hypertension, flushing, neck stiffness; associated with ingestion of large amounts of tyramine-rich food (aged cheese/meat, cured meats, some alcoholic beverages, sauerkraut); may be caused by MAOI overdose, treat with nifedipine (10 mg orally) or phentolamine; orthostatic hypotension, sedation, headache, sexual dysfunction, decreased sleep, fatigue; serotonin syndrome

i. Signs/symptoms: rest tremor, myoclonus, hypertonicity, hyperthermia, hallucinations

ii. Results from combining serotonergic drugs; combinations including an MAOI are the most dangerous.

iii. NB: Avoid other serotonergic, adrenergic, or dopaminergic drugs for 2 weeks before or after ingestion of an MAOI.

3. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)

a. Uses: depressive disorders, anxiety disorders, premenstrual dysphoric disorder

b. Examples:

Fluoxetine (Prozac®) | Paroxetine (Paxil®) |

Sertraline (Zoloft®) | Fluvoxamine (Luvox®) |

Citalopram (Celexa®) | Escitalopram (Lexapro®) |

c. Distinguishing characteristics: in most respects, the SSRIs are relatively interchangeable; most differences are pharmacokinetic.

i. Fluoxetine: NB: parent drug has a long half-life (t1/2) (5 days) and a long-lived active metabolite (norfluoxetine, t1/2= 10 days); requires 3- to 4-week washout period before initiation of MAOI; cytochrome 2D6 and 3A4 inhibitor.

ii. Paroxetine: NB: most anticholinergic; very short t1/2 can cause severe withdrawal syndrome; cytochrome 2D6 inhibitor; a controlled-release version is now available.

iii. Fluvoxamine: initially marketed for obsessive-compulsive disorder; cytochrome 1A2 inhibitor

iv. Sertraline: can sometimes inhibit warfarin (Coumadin®) metabolism

v. Citalopram: the most serotonin-specific; U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a black-box warning in 2012: doses greater than 40 mg associated with abnormal heart rhythms—QT interval prolongation

vi. Escitalopram: the L-isomer of citalopram; has fewer side effects

d. Major side effects of SSRIs

i. Common, reversible side effects include nausea, diarrhea, sexual dysfunction, headache, and anxiety.

ii. NB: Mania can be induced even in patients without prior history of bipolar disorder.

iii. Start at low initial dose and titrate slowly to minimize side effects.

iv. Pregnancy class C (uncertain safety, no adverse effects in studies)

![]() NB:

NB:

Paroxetine is the most potent SSRI, citalopram is the most selective, and fluoxetine is the longest lasting.

![]() NB:

NB:

Sertraline is also a potent blocker of the DA transporter.

![]() NB:

NB:

Serotonin syndrome results from medications that enhance serotonin transmission (via decreased breakdown or increased production). Combinations of MAOIs and SSRIs, TCA, or dextromethorphan should be avoided. Serotonin syndrome can be differentiated from neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) by the presence of shivering and myoclonus.

4. Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

a. NB: Venlafaxine (Effexor XR®): works through 5-HT reuptake inhibition, but also inhibits NE reuptake at higher doses; side effects: mild diastolic hypertension (5–10 mm Hg in 5%–10% of patients); withdrawal syndrome (myalgias, restlessness, poor energy); other side effects similar to the SSRIs

b. Desvenlafaxine (Pristiq®): contains the active metabolite of venlafaxine; similar mechanism of action and side effects

c. Duloxetine (Cymbalta®): inhibits serotonin and NE reuptake, approved for depression, neuropathic pain, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), fibromyalgia; side effects similar to other SNRIs; side effects also include elevation of liver enzymes

5. Other antidepressants

a. Bupropion (Wellbutrin®, Zyban®): increases NE activity; also increases DA activity at very high doses; no sexual dysfunction; side effects: NB: lowers seizure threshold, avoid in patients with seizure risk factors, increased seizure risk in patients with eating disorders, increased risk with single doses greater than 300 mg or total daily dose greater than 450 mg; can cause irritability and anxiety; also used as a smoking cessation aid (Zyban); approved for treatment of attention deficit disorder

b. Mirtazapine (Remeron®): enhances 5-HT and NE transmission; postsynaptic 5-HT1A agonist, presynaptic 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 antagonist, presynaptic α2 antagonist; no sexual dysfunction; anti-H1 side effects (weight gain, drowsiness)

c. Nefazodone (Serzone®): enhances 5-HT and NE neurotransmission: 5-HT reuptake inhibition, presynaptic 5-HT2 antagonism, synaptic NE reuptake inhibition (?); minimal sexual dysfunction; can cause hepatic dysfunction and is sedating

d. Trazodone (Desyrel): mostly serotonergic; 5-HT reuptake inhibition, presynaptic 5-HT2 antagonist, postsynaptic 5-HT agonist at high doses (?); side effects: NB: priapism, drowsiness, sexual dysfunction

e. Vilazodone (Vibryd®): serotonin reuptake inhibitor and 5-HT1A receptor partial agonist; moderate effect on 5-HT4; may have fewer sexual side effects, may help irritable bowel syndrome (IBS); side effects: diarrhea, nausea, vomiting (likely due to 5-HT4), headache (HA)

f. Vortioxetine (Brintellix®): serotonin reuptake inhibitor, 5-HT1A agonist, 5-HT1B partial agonist, 5-HT3/5-HT1D/5-HT7 antagonist; multimodal action is thought to increase dopamine, norepinephrine, acetylcholine in prefrontal cortex, thought to help with the cognitive deficits associated with depression

g. Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

i. Indications: medication-resistant depression (80% efficacy), Parkinson’s disease (PD), mania, acute psychosis, neuroleptic malignant syndrome

ii. Procedure involves delivery of a small current to the brain, under anesthesia, to induce a generalized seizure.

iii. Mechanism of action unknown: massive monoamine release (?); “resetting” of frontal subcortical systems (?)

iv. Side effects: major side effect is temporary anterograde and retrograde amnesia; other side effects include risks of anesthesia (cardiac arrest, allergic reaction); modern anesthetics and paralytic agents have virtually eliminated risk of broken bones, tongue biting, and broken teeth from the seizure; effect is temporary, usually requires multiple treatments.

C. Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation: application of magnetic field to frontal part of brain, presumably inducing current and neurotransmitter release; may have efficacy in treatment-resistant depression; parameters not fully established

D. Antimanic and mood-stabilizing agents

1. Uses in psychiatry

a. Treatment of mania; the antipsychotics risperidone and quetiapine can treat acute mania; acute mania and mania prophylaxis:

Lithium (Eskalith®)

Carbamazepine (Tegretol®)

Lamotrigine (Lamictal®)

Valproate (Depakote®)

Olanzapine (Zyprexa®)

b. Also used in treatment of impulse control disorders, agitation, and aggression

c. Some can also treat bipolar depression (lithium, lamotrigine).

2. Lithium (therapeutic levels 0.6–1.2)

a. Theories about mechanism of action include effects on second messenger systems, serotonergic neurotransmission, and neuronal ion channels.

b. Acute side effects: tremor, ataxia, acne, weight gain, polyuria, hypokalemia

c. Chronic side effects: hypothyroidism, psoriasis, weight gain

d. Reduces the risk of suicide in bipolar disorder and major depression

e. NB: Toxicity: symptoms: delirium, tremor, ataxia, diarrhea, seizure, QT prolongation, renal failure; risk of toxicity increases with dehydration, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, phenytoin; dialyze for level greater than 3.0.

3. Antimanic antiepileptics (carbamazepine, valproate, lamotrigine)

4. Antimanic antipsychotics (olanzapine, quetiapine, risperidone)

E. Review of pharmacology of antipsychotics

1. Uses in neurology

a. PD-related psychosis: clozapine and quetiapine have lowest risk of worsening parkinsonism; less D2 blockade; substantial anti-ACh activity, pimavanserin—a 5-HT2A serotonin receptor inverse agonist may be a new option for the treatment of psychosis in PD with little or no extrapyramidal side effects.

b. Dementia/sundowning: atypicals preferred; avoid agents with strong anticholinergic or antihistaminic properties; use low nighttime doses to reduce treatment-emergent side effects; black-box warning: antipsychotics increase the risk of death in patients suffering from dementia.

c. NB: Tic disorders (including Tourette’s): high-potency antipsychotic (pimozide or haloperidol)

2. Uses in psychiatry

a. Psychotic disorders (schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder)

b. Mood disorders (psychotic depression, mania)

3. “Typical” antipsychotics (neuroleptics): work mainly through D2 blockade

a. Low-potency neuroleptics (typical daily dose >100 mg)

i. Significant anti-ACh, anti-NE, and anti-H1 activity

ii. Examples: chlorpromazine (Thorazine®), thioridazine (Mellaril®)

iii. NB: The antiemetics prochlorperazine (Compazine®), promethazine (Phenergan®), and metoclopramide (Reglan®) have similar pharmacology and side effects.

b. High-potency neuroleptics (typical daily dose <50 mg)

i. Higher ratio of anti-DA to anti-ACh—increased risk of EPSs

ii. Low antiadrenergic and anti-H1 activity

iii. Examples: haloperidol (Haldol®), thiothixene (Navane®), fluphenazine (Prolixin®)

4. “Atypical” antipsychotics

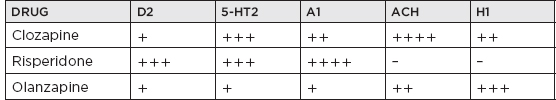

a. Defined by 5-HT2 > DA blockade and D4 > D2 blockade; NB: much lower incidence of EPS and TD than typical agents; increased efficacy for negative symptoms of schizophrenia and cognition

i. Clozapine (Clozaril®): most effective antipsychotic; NB: clozapine causes no EPSs; safely treats PD-related psychosis; approved for treatment of TD; side effects: NB: idiosyncratic agranulocytosis (~1% incidence), weekly complete blood count for 6 months, then biweekly complete blood count for duration of treatment, hold or discontinue clozapine if white blood count or neutrophil count declines, NB: lowers seizure threshold (0.7%–1.0% per 100-mg daily dose), severe anti-ACh and anti-H1 side effects—sialorrhea (excessive salivation)

ii. Olanzapine (Zyprexa®): massive weight gain and moderate sedation because of anti-ACh effects; the only atypical antipsychotic approved for prophylaxis against mania

iii. Quetiapine (Seroquel®): mostly blocks 5-HT2 receptors; minimal DA blockade at usual doses; NB: useful in patients with PD; anti-H1 activity causes weight gain and sedation; α1 blockade causes orthostatic hypotension.

iv. Risperidone (Risperdal®): the highest D2/5-HT2 blockade ratio of the atypicals; dose-related EPSs at greater than 6 mg/day; hyperprolactinemia—caused by tuberoinfundibular DA blockade (DA suppresses prolactin release), decreased libido, gynecomastia, sexual dysfunction; orthostatic hypotension because of α1 blockade

v. Ziprasidone (Geodon®): powerful 5-HT2 and DA receptor antagonist; no weight gain; high D2 affinity suggests EPS may prove to be a problem; significant α1 blockade—may cause hypotension; prolongation of QT interval (clinically insignificant)

vi. Aripiprazole (Abilify®): new form of antipsychotic—partial agonist; extremely high affinity at D2 and 5-HT2A receptor

vii. Paliperidone (Invega®): major active metabolite of risperidone; compared to risperidone it has easier dissociation from the D2 receptors; thought less likely to cause EPS; primary renal metabolism, but does not interfere with lithium metabolism

viii. Asenapine (Saphris®): high-affinity antagonist at 5-HT1A, 5-HT1B, 5-HT2A, 5-HT2B, 5-HT2C, 5-HT5-7, serotonin receptors, as well as D1 to D4 dopaminergic receptors; not recommended in patients with severe hepatic impairment

ix. Lurasidone(Latuda®): antagonist at D2 and serotonin 5-HT2A and 5-HT7; partial agonist at 5-HT1A; should be administered with food; serum concentration of lurasidone is greatly increased by ketoconazole, rifampin, and diltiazem (CYP3A4 inhibitors).

5. Quick reference chart: atypical antipsychotic receptor affinities

6. Lasting intramuscular depot formulations

a. Haloperidol decanoate (3–4 weeks)

b. Fluphenazine decanoate (2 weeks)

c. Risperidone (Risperdal Consta®) (2 weeks)

d. Aripiprazole (Abilify Maintena®) (4 weeks)

7. NB: EPS—“3 hours, 3 days, 3 weeks”; likelihood of EPS usually correlates with degree of DA blockade

a. Acute dystonia (usually occurs within 3 hours): usually occurs with parenteral high-potency medications; young men, particularly of African descent, are at higher risk; usually involves midline musculature, oculogyrus, opisthotonus, torticollis, retrocollis; treat with intramuscular/intravenous diphenhydramine (Benadryl®) or benztropine (Cogentin®).

b. Akathisia (within 3 days): “inner restlessness”; most common EPS; patients fidget, get up and walk around, and are unable to sit quietly; treat with propranolol (Inderal®), benzodiazepine, or anticholinergic.

c. Parkinsonism (approximately 3 weeks): occurs with high-potency typicals and risperidone (usually >6 mg/day); features that distinguish EPS from idiopathic PD: EPS parkinsonism is usually symmetric, EPS parkinsonism usually has subacute onset, tremor is typically less prominent than rigidity and bradykinesia; treatment: reduce antipsychotic dose, add anticholinergic, switch to a “more atypical” drug (i.e., lower D2/5-HT2 blockade ratio).

8. TD: incidence 3% to 5% per year of treatment with DA-blocking agent; caused by chronic DA blockade, resulting in striatal D2 receptor hypersensitivity; elderly, female patients and those with underlying central nervous system (CNS) disease are at greater risk for developing TD; syndrome consists of choreoathetoid movements that can occur anywhere in the body, with the face (buccolingual) being the most commonly affected region; treatment: decrease dose of antipsychotic—may cause worsening initially because DA receptors are left unblocked; switch to atypical antipsychotic; clozapine does not cause EPS and is indicated for treatment of TD; mixed success with benzodiazepines, anticholinergics, gabapentin, and vitamin E.

9. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome: incidence less than 1%

a. Results from decreased dopaminergic neurotransmission

i. Usually results from addition of DA receptor blocker (i.e., antipsychotic)

ii. Can happen with removal of DA receptor stimulator (i.e., anti-PD medications)

b. Causes of increased risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome: affective disorder, concomitant lithium use, sudden decrease of DA agonist or increase of DA antagonist

c. Symptoms/signs: earliest sign is mental status change (confusion, irritability); physical signs: rigidity, fever, autonomic instability, tremor, diaphoresis; labs: ↑ creatine phosphokinase (usually >1,000), ↑ white blood count, myoglobinuria

d. Treatment: discontinue antipsychotic; supportive care in the intensive care unit, especially cooling and hydration; bromocriptine (DA agonist), dantrolene (muscle relaxant); ECT in refractory cases; patients usually tolerate rechallenge with antipsychotic

![]() NB:

NB:

Paroxysmal autonomic instability with dystonia (PAID) is a common symptom cluster similar to NMS and commonly appears following severe traumatic or hypoxic brain injury. Treatment consists of beta-adrenergic blockers, opiod analgesia, DA agonists, and benzodiazepines. DA antagonists can precipitate PAID-like symptoms. Anticholinergics and SSRIs are largely ineffective.

F. Anxiolytics and hypnotics

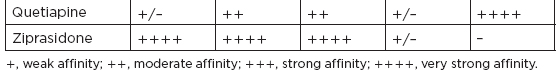

1. Benzodiazepines

a. General properties

i. All facilitate GABAA receptor (ligand-gated chloride channel) by binding to its benzodiazepine site.

ii. Actions include muscle relaxation, sedation, and amnesia.

b. Indications and uses

i. Primary sleep disorders (REM behavior disorder, restless limbs)

ii. Anxiety disorders (panic disorder, generalized anxiety, phobias, social anxiety disorder)

iii. Sedation (for agitated patients or medical procedures)

iv. Muscle spasticity

v. Alcohol, benzodiazepine, or barbiturate withdrawal

vi. Epilepsy

c. Should be used for a brief, well-defined duration

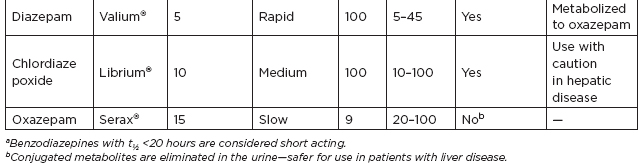

d. Tolerance and/or dependence can develop with all—more likely with rapidly absorbed and short-acting (t1/2 <20 hours) compounds.

e. Contraindicated in patients with substance use disorders; can impair memory and cognitive and motor performance

f. Duration of clinical activity is usually significantly shorter than t1/2.

g. Quick reference chart: benzodiazepines

2. Barbiturates: no longer commonly used in psychiatry, but still used as anticonvulsants

a. Risks: generally similar to those of benzodiazepines; can cause respiratory depression and severe hypercarbia/hypoxia; can induce hepatic enzymes, causing rapid elimination of other medications

b. Modern uses of barbiturates

i. Amobarbital (Amytal®): used for drug-assisted interviews

ii. Phenobarbital (Luminal®)

iii. Seizure prophylaxis

iv. Medication of choice for barbiturate withdrawal

v. Methohexital (Brevital®): an ultra-short-acting parenteral barbiturate; the most popular anesthetic for ECT and other brief surgical procedures

vi. Pentobarbital (Nembutal®): used to control status epilepticus

3. Zolpidem (Ambien®) and zaleplon (Sonata®): short-acting nonbenzodiazepine compounds that interact with the benzodiazepine binding site; approved for the treatment of insomnia; cannot be used to treat benzodiazepine withdrawal or muscle spasm; zolpidem: longer acting

4. Buspirone (BuSpar®): 5-HT1A receptor agonist; requires weeks to obtain therapeutic effect (similar to antidepressants); no dependence, abuse potential, or withdrawal side effects; not effective for benzodiazepine or barbiturate withdrawal

G. Medications for treatment of substance-related disorders

1. Flumazenil (Mazicon®, Romazicon®): benzodiazepine receptor antagonist; used to reverse benzodiazepine toxicity; may precipitate seizures or severe anxiety in patients who are epileptic, benzodiazepine-dependent, or have ingested a large quantity of benzodiazepines; t1/2 less than 15 minutes; dose in 0.2- to 0.5-mg increments, to max dose of 3 mg/hour

2. Opioid abuse treatments

a. Naloxone (Narcan®): parenteral opioid antagonist; used to reverse effects of opioid toxicity

b. Naltrexone (ReVia®): competitive antagonist at opioid receptors; used to maintain drug-free state in patients treated for opioid dependence

c. Methadone (Dolophine®, Methadose®): once-daily opioid agonist; used to replace more illegal, injected, or more addictive opioids; patient remains narcotic-dependent but under a physician’s care

d. Buprenorphine (Buprenex®): partial mu-opioid agonist, alternative to methadone, sublingual and can be prescribed in a clinician’s office in the United States; less lethal in overdose than methadone

e. Disulfiram (Antabuse®): used for patients being treated for ETOH dependence; requires high level of motivation and compliance; ETOH—(ETOH dehydrogenase) → acetaldehyde—(aldehyde dehydrogenase) → acetic acid; disulfiram inhibits aldehyde dehydrogenase, causing accumulation of acetaldehyde; causes multiple unpleasant effects—nausea, headache, diaphoresis, vomiting, tachycardia, vertigo; can cause severe reactions to ETOH in food (desserts, sauces), medicine (cough suppressant), or topical products (aftershave, perfume); can cause death and is contraindicated in patients with pulmonary or cardiac illness; long t1/2 necessitates 2-week washout of disulfiram before ETOH is used again.

H. β-blockers: effective for social anxiety, medication-induced tremors, and akathisia; used to treat agitation and aggression; propranolol (Inderal®) and metoprolol (Lopressor®) have better CNS penetration because they are more lipophilic; pindolol has been used to augment antidepressants.

I. Psychosurgery: frontal lobotomy, used in the past, is no longer an acceptable therapeutic option; capsulotomy for treatment of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); stereotactic radioablation of small portions of the internal capsule in the region of the caudate; micro-electrode deep-brain stimulation of the same area is being studied.

II: Psychiatric Illnesses The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (currently in its 5th edition, DSM-5) strictly defines psychiatric disorders; for practical purposes, less rigid criteria are often employed with real patients; in general, all diagnoses (except personality disorders) can be made only if there is a change from prior functioning, significant impairment or distress in the patient, and the behavior has no other reasonable cause (medications, medical illness, bereavement, etc.).

A. Mood disorders

1. Mood states

a. Major depressive episode: at least 2 weeks of symptoms representing a change from prior functioning; five or more of the following symptoms (NB: SIGECAPS):

i. Depressed mood

ii. Alteration in Sleep patterns (hypersomnia or insomnia)

iii. Diminished Interest or pleasure (anhedonia)

iv. Excessive Guilt or feelings of worthlessness

v. Decreased Energy or fatigue nearly every day

vi. Impaired Concentration or unusual indecisiveness

vii. Change in Appetite or weight (±5%)

viii. Unusual Psychomotor activity (agitation or retardation)

ix. Thoughts of Suicide or death; one of the symptoms must be depressed mood or anhedonia; major depressive episode must not be attributable to depressive symptoms that result from many medications (β blockers), or medical illnesses (hypothyroidism, B12 deficiency, cancer, lupus, stroke [30%], myocardial infarction [30%])

b. Manic episode: at least 1 week of symptoms (or need for hospitalization) representing a change from prior functioning; elevated, expansive, or irritable mood; at least three of the following symptoms (NB: DIGFAST), four if mood is predominantly irritable:

i. Distractibility

ii. Insomnia without tiredness

iii. Grandiose ideas or behavior (exaggerated sense of importance)

iv. Flight of ideas (constant shifting between connected concepts)

v. Agitation or increased activity

vi. Speech excessive and/or pressured (pressure: internal drive to talk)

vii. Thoughtless or reckless behavior; must cause marked social and/or occupational impairment

c. Hypomanic episode

i. Requires only 4 days of manic symptoms

ii. Symptoms must be observable by others but not severe enough to cause marked impairment.

iii. Cannot be severe enough to cause hospitalization and/or psychosis

d. Mixed episode

i. Meets criteria for both major depressive and manic episodes almost every day for at least a week

ii. Symptoms must cause marked impairment.

iii. Mania, hypomania, or mixed episodes may be induced by antidepressants, corticosteroids, stimulants, and right-sided cerebral damage.

2. Mood disorder diagnoses

a. Major depressive disorder: one or more major depressive episodes

i. Epidemiology: 15% lifetime prevalence; twice as common in females

ii. Risk factors: genetics (having a first-degree relative with mood disorder confers risk); other psychiatric illness (personality disorders, anxiety disorders); neurologic illnesses (Parkinson’s, 40%–50%; multiple sclerosis, 50%; epilepsy, 40%–50%); pregnancy

iii. Neuropsychiatric research findings: associated with decreased frontal metabolism on PET scanning; associated with left frontal brain injury; decreased 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid in cerebrospinal fluid of suicidal patients

iv. Suicide risk factors: genetics (family history of suicide); medical (intoxication, chronic medical illness); gender (successful suicide is 3 times more common in males, suicide attempts are 4 times more common in females); psychiatric: prior suicide attempt, psychosis, substance use disorder; advanced age (peak rates occur in men >45 years old (y/o), and in women >55 y/o, high rate of completion in patients >65 y/o, but remember that suicide is the second-leading cause of death for adolescent males [accidents are the first])