Adulthood

For most of the history of developmental psychology, the predominant theory held that development ended with childhood and adolescence. Adults were considered to be finished products in whom the ultimate developmental states had been reached. Beyond adolescence, the developmental point of view was relevant only insofar as success or failure to reach adult levels or to maintain them determined the maturity or immaturity of the adult personality.

In contradistinction were the long-recognized ideas that adult experiences, such as pregnancy, marriage, parenthood, and aging, had an obvious and significant impact on mental processes and experience in the adult years. This view of adulthood suggests that the patient, of any age, is still in the process of ongoing development, as opposed to merely being in possession of a past that influences mental processes and is the primary determinant of current behavior. Although the debate continues, the idea that development continues throughout life is increasingly accepted.

Development in adulthood, as in childhood, is always the result of the interaction among body, mind, and environment, never exclusively the result of any one of the three variables. Most adults are forced to confront and adapt to similar circumstances: establishing an independent identity, forming a marriage or other partnership, raising children, building and maintaining careers, and accepting the disability and death of one’s parents.

In modern Western societies, adulthood is the longest phase of human life. Although the exact age of consent varies from person to person, adulthood can be divided into three main parts: young or early adulthood (ages 20 to 40), middle adulthood (ages 40 to 65), and late adulthood or old age.

YOUNG ADULTHOOD (20 TO 40 YEARS OF AGE)

Usually considered to begin at the end of adolescence (about age 20) and to end at age 40, early adulthood is characterized by peaking biological development, the assumption of major social roles, and the evolution of an adult self and life structure. The successful passage into adulthood depends on satisfactory resolution of childhood and adolescent crises.

During late adolescence, young persons generally leave home and begin to function independently. Sexual relationships become serious, and the quest for intimacy begins. The 20s are spent, for the most part, exploring options for occupation and marriage or alternative relationships and making commitments in various areas.

Early adulthood requires choosing new roles (e.g., husband, father) and establishing an identity congruent with those new roles. It involves asking and answering the questions “Who am I?” and “Where am I going?” The choices made during this time may be tentative; young adults may make several false starts.

Transition from Adolescence to Young Adulthood

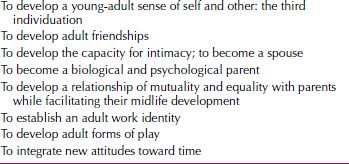

The transition from adolescence to young adulthood is characterized by real and intrapsychic separation from the family of origin and the engagement of new, phase-specific tasks (Table 32-1). It involves many important events, such as graduating from high school, starting a job or entering college, and living independently. During these years, the individual resolves the issue of childhood dependency sufficiently to establish self-reliance and begins to formulate new, young-adult goals that eventually result in creation of new life structures that promote stability and continuity.

Table 32-1

Table 32-1

Development Tasks of Young Adulthood

Developmental Tasks

Establishing a self that is separate from parents is a major task of young adulthood. For most individuals, the emotional detachment from parents that takes place in adolescence and young adulthood is followed by a new inner definition of themselves as comfortably alone and competent, able to care for themselves in the real world. This shift away from the parents continues long after marriage, and parenthood results in the formation of new relationships that replace the progenitors as the most important individuals in the young adult’s life.

Psychological separation from the parents is followed by synthesis of mental representations from the childhood past and the young-adult present. The psychological separation from parents in adolescence has been called the second individuation, and the continued elaboration of these themes in young adulthood has been called the third individuation. The continuous process of elaboration of self and differentiation from others that occurs in the developmental phases of young (20 to 40 years of age) and middle (40 to 65 years of age) adulthood is influenced by all important adult relationships.

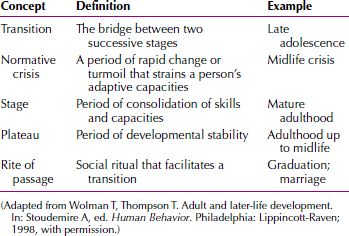

A number of different models have been proposed for understanding adult development. They are all theoretical and somewhat idealized. They all use metaphors to describe complex social, psychological, and interpersonal interactions. The models are heuristic: They provide a conceptual framework for thinking about common important experiences. They are descriptive rather than prescriptive; that is, they provide a useful way of looking at what many persons do, not a formula for what all persons should do. Some of the terms and concepts commonly used are explained in Table 32-2. These periods involve individuation, that is, leaving the family of origin and becoming one’s own man or woman, passing through midlife, and preparing in middle adulthood for the transition into late adulthood.

Table 32-2

Table 32-2

Psychological Development Concepts

Work Identity. The transition from learning and play to work may be gradual or abrupt. Socioeconomic group, gender, and race affect the pursuit and development of particular occupational choices. Blue-collar workers generally enter the workforce directly after high school; white-collar workers and professionals usually enter the workforce after college or professional school. Depending on choice of career and opportunity, work may become a source of ongoing frustration or an activity that enhances self-esteem. Symptoms of job dissatisfaction are a high rate of job changes, absenteeism, mistakes at work, accident proneness, and even sabotage.

UNEMPLOYMENT. The effects of unemployment transcend those of loss of income; the psychological and physical tolls are enormous. The incidence of alcohol dependence, homicide, violence, suicide, and mental illness rises with unemployment. One’s core identity, which is often tied to occupation and work, is seriously damaged when a job is lost, whether through firing, attrition, or early or sometimes even regular retirement.

A young adult female patient had greatly enjoyed her 5 years in college and only reluctantly accepted a job with a large real estate firm. During college, she had had limited interest in her appearance, and she began work in clothing borrowed from family and friends. She scoffed when her boss began to criticize her dress and gave her an advance to buy an upscale wardrobe, but she then began to enjoy the fine clothing and the respect engendered by her appearance and position. As her income began to rise, work became a source of pleasure and self-esteem and the way to acquire some of the trappings of adulthood. (Courtesy of Calvin Colarusso, M.D.)

Developing Adult Friendships. In late adolescence and young adulthood, before marriage and parenthood, friendships are often the primary source of emotional sustenance. Roommates, apartment mates, sorority sisters, and fraternity brothers, as indicated by the names used to describe them, are substitutes for parents and siblings, temporary stand-ins until more permanent replacements are found.

The emotional needs for closeness and confidentiality are largely met by friendships. All major developmental issues are discussed with friends, particularly those in similar circumstances. As marriages occur and children are born, the central emotional importance of friendships diminishes. Some friendships are abandoned at this point, because the spouse objects to the friend, recognizing at some level that they are competitors. Gradually, there is movement toward a new form of friendship, couples friendships. They reflect the newly committed status but are more difficult to form and to maintain, because four individuals must be compatible, not just two.

As children begin to move out of the family into the community, parents follow. Dance classes and Little League games provide the progenitors with a new focus and the opportunity to make friends with others who are at the same point developmentally and who are receptive to the formation of relationships that help explain, and cushion, the pressures of young adult life.

Sexuality and Marriage. The developmental shift from sexual experimentation to the desire for intimacy is experienced in young adulthood as an intense loneliness, resulting from the awareness of an absence of committed love similar to that experienced in childhood with their parents. Brief sexual encounters in short-lived relationships no longer significantly boost self-esteem. Increasingly, the desire is for emotional involvement in a sexual context. The young adult who fails to develop the capacity for intimate relationships runs the risk of living in isolation and self-absorption in midlife.

For most individuals in Western culture, the experience of intimacy increases the desire for marriage. Most persons in the United States marry for the first time in their mid- to late 20s. The median age of first marriage has been rising steadily since 1950 for both men and women, and the number of persons who never marry has been increasing. Today, approximately 50 percent of all adults ages 18 and older are not married, compared with only 28 percent in 1960. The proportion of 30- to 34-year-olds who never married has almost tripled, and the proportion of never-married 35- to 39-year-olds doubled.

INTERRACIAL MARRIAGE. Mixed-race marriages were banned in 19 states until a U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1967. In 1970, such marriages accounted for only 2 percent of all marriages. The trend has been steadily upward. Currently, interracial marriages account for about 1.5 million marriages in the United States.

Despite the trend toward more interracial marriages, they still remain a small proportion of all marriages. Most persons are more likely to marry someone from the same racial and ethnic background. Marriages between Hispanic whites and non-Hispanic whites and between Asians and whites are more common than those between blacks and whites.

SAME-SEX MARRIAGE. Same-sex marriage is recognized as legal by many states in the United States and by the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in several countries around the world (e.g., France and Denmark). It differs from same-sex civil unions granted by states, which do not provide the same federal protection or benefits as marriage. No reliable estimates are available for the number of same-sex marriages in the United States; however, in 2013 it was estimated to be about 80,000. There is growing consensus in the United States and around the world that homosexual persons should be allowed the same marital rights and privileges as heterosexuals. Same-sex marriage can be subject to more stress than heterosexual marriage because of continued prejudice toward such unions among certain conservative political or religious groups who oppose such unions.

MARITAL PROBLEMS. Although marriage tends to be regarded as a permanent tie, unsuccessful unions can be terminated, as indeed they are in most societies. Nevertheless, many marriages that do not end in separation or divorce are disturbed. In considering marital problems, clinicians are concerned with both the persons involved and with the marital unit itself. How any marriage works relates to the partner selected, the personality organization or disorganization of each, the interaction between them, and the original reasons for the union. Persons marry for a variety of reasons—emotional, social, economic, and political, among others. One person may look to the spouse to meet unfulfilled childhood needs for good parenting. Another may see the spouse as someone to be saved from an otherwise unhappy life. Irrational expectations between spouses increase the risk of marital problems.

MARRIAGE AND COUPLES THERAPY. When families consist of grandparents, parents, children, and other relatives living under the same roof, assistance for marital problems can sometimes be obtained from a member of the extended family with whom one or both partners have rapport. With the contraction of the extended family in recent times, however, this source of informal help is no longer as accessible as it once was. Similarly, religion once played a more important role than it does now in the maintenance of family stability. Wise religious leaders are available to provide counseling, but they are not sought out to the extent they once were, which reflects the decline in religious influence among large segments of the population. Formerly, both the extended family and religion provided guidance for couples in distress and also prevented dissolution of marriages by virtue of the social pressures that the extended family and religion exerted on couples to stay together. As family, religious, and societal pressures have been relaxed, legal procedures for relatively easy separation and divorce have expanded. Concurrently, the need for formalized marriage counseling services has developed.

Marital therapy is a form of psychotherapy for married persons in conflict with each other. A trained person establishes a professional contract with the patient-couple and, through definite types of communication, attempts to alleviate the disturbance, to reverse or change maladaptive patterns of behavior, and to encourage personality growth and development.

In marriage counseling, only a particular conflict related to the immediate concerns of the family is discussed; marriage counseling is conducted much more superficially by persons with less psychotherapeutic training than is marital therapy. Marital therapy places greater emphasis on restructuring the interaction between the couple, including, at times, exploration of the psychodynamics of each partner. Both therapy and counseling emphasize helping marital partners cope effectively with their problems.

Parenthood. Parenthood intensifies the relationship between the new parents. Through their physical and emotional union, the couple has produced a fragile, dependent being that needs them in the interlocking roles of father and mother. This recognition expands their internal images of each other to include thoughts and feelings emanating from the role of parent. As they live together as a family, the lovers’ relationship to each other changes. They become parents relating to one another and to their children.

Parent–child problems do arise, however. In addition to the economic burden of raising a child (estimated to be $250,000 for a middle-class family whose child goes to college), there are emotional costs. Children may reawaken conflicts that parents themselves had as children, or children may have chronic illnesses that challenge families’ emotional resources. In general, men have been more concerned with their work and occupational advancement than with child rearing, and women have been more concerned about their role as mothers than with advancement in their occupation, but this emphasis is changing dramatically for both sexes. A small, but growing, number of couples are choosing to split a job (or work at two part-time jobs) and share child-rearing duties.

Parenting has been described as a continuing process of letting go. Children must be allowed to separate from parents and, in some cases, must be encouraged to do so. Letting go involves separation from children who are starting school. School phobias and school refusal syndromes that are accompanied by extreme separation anxiety may have to be dealt with. Often, a parent who cannot let go of a child accounts for this situation; some parents want their children to remain tightly bound to them emotionally. Family therapy that explores these dynamics may be needed to resolve such problems.

As children get older and enter adolescence, the process of establishing identity assumes great importance. Peer relationships become crucial to a child’s development, and overprotective parents who keep a child from developing friendships or having the freedom to experiment with friends that the parents disapprove of can interfere with the child’s passage through adolescence. Parents need not refrain from exerting influence over their children; guidance and involvement are crucial. But they must recognize that adolescents especially need parental approval; although rebellious on the surface, adolescents are much more tractable than they appear, provided parents are not overbearing or generally punitive.

SINGLE-PARENT FAMILIES. More than 10 million single-parent families exist with one or more children under the age of 18; of these families, 20 percent are single-parent homes in which a woman is the sole head of the household. The increase in number of single-parent families has risen almost 200 percent since 1980.

ALTERNATIVE LIFESTYLE PARENTING.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree