OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define advocacy.

Describe levels of advocacy in the care of underserved and vulnerable communities.

Illustrate ways health professionals can engage in advocacy.

Provide a menu of activities for community advocacy.

Michael lives with his family in North Richmond, California, a city with five oil refineries. His 6-year-old daughter has been to the emergency department three times in the past few months for respiratory complaints, as have many of her classmates at school. Michael’s bronchitis has been lingering for quite some time and last year he had a heart attack. The refineries are known to release high levels of air pollutants including carcinogens and chemicals that cause respiratory and neurologic problems. Michael suspects that the pollution spewing from the refineries contributes to illness in the community. Michael’s wife is pregnant and he worries about harmful effects of the pollution on his unborn son. Because North Richmond is his home and he cannot afford to live anywhere else, Michael feels frustrated and helpless.

INTRODUCTION

The term “advocacy” often conjures images of rallies, marches, and protests. But at its core, advocacy is an activity on someone else’s behalf directed toward a specific goal. For the health professional, the “goal” and the “someone” are clear: a better state of health for patients.

Medical professionals’ obligation to advocate for their patients is often conceived as a fundamental professional duty. Entrusted with the details of patients’ life, their hopes, and concerns, medical providers are obligated to use this intimate knowledge to their patients’ benefit. Although doctors, nurses, and other health professionals engage in daily advocacy on behalf of their patients (for example, helping patients obtain medications or disability benefits), aspirational definitions of physician, and other health professional roles include not only the promotion of the health of individual patients but also of society as a whole.

In its Declaration of Professional Responsibility, the American Medical Association declares, “humanity is our patient.” Physicians are asked to pledge to “… respect human life and the dignity of every individual; … and to … advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.”1 The American Nursing Association likewise defines nursing’s role as “… alleviation of suffering …, and advocacy in the care of individuals, families, communities, and populations.”2 In this chapter, we focus on these broader community and population advocacy efforts, explore the roles clinicians can play, and present practical advocacy tools.

TYPES AND LEVELS OF ADVOCACY

Clinician advocacy starts with providing care that integrates the full spectrum of a patient’s needs. Examples include helping patients navigate complex health care systems, asking pharmacies and insurance companies to cover specific medications, and referring patients to social service agencies.

Advocacy at the individual patient level is a core component of every provider’s professional obligations. However, this obligation extends beyond the provision of good clinical care to a responsibility to address systemic inequities and abuses as well. At the institutional level, for example, clinical providers can be instrumental in advocating for system changes that improve care. Examples of institutional advocacy include convincing the hospital leadership to expand interpreter services or to institute more generous charity care policies.

Health-care advocacy targeting health-care system policies or societal laws governing health care is another level of health-care activism. Advocacy may take the broad form of support for a single-payer system or research into areas of political contention, like use of needle exchange to prevent HIV transmission. Providers may advocate on behalf of patients by acting to change health-care regulations, such as protesting against the imposition of short hospital stays for obstetrical deliveries, or challenging gag laws that prohibit them from informing patients of therapeutic options not covered by their insurance or inquiring about firearms in the home.

Another level of health professional engagement is community-based advocacy, which can have an impact on the broader population beyond the patients seen in any particular health-care setting. Medical professionals and their patients have advocated for changes in policies from support for social welfare programs, food policy, public support of housing, education, and prison reform to increased funding for research and health-care delivery for diseases from HIV to Parkinsonism.

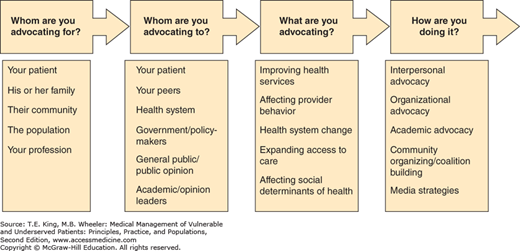

While we use a framework of clinician, institutional, healthcare and community level advocacy, thee are other ways of categorizing advocacy efforts. Some define advocacy in terms of audience, issue, and method (Figure 8-1). Others have proposed distinguishing between the levels of advocacy calling working on behalf of the interests of a specific patient “agency” and reserving “activism,” for efforts directed at changing social conditions that undermine health, particularly those that undermine population more than individual health. Agency, in this schema, is “about working the system, engaging in activism is about changing the system.”3

Figure 8-1.

Recognizing levels of advocacy. (From O’Toole T. Advocacy. In: King TE Jr, Wheeler M, Bindman A, Fernandez A, Grumbach K, Schillinger D, Villela T. (eds). Medical Management of Vulnerable & Underserved Patients: Principles, Practice, & Populations. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2007:429-436.)

Medical research can also be conceived of as another form of advocacy. Indeed, research is one of the professions’ most powerful tools to change both the delivery of care to individuals and influence broader public policy. Beyond documenting best practices in health-care delivery and advancing scientific knowledge, medical research also has been pivotal to supporting broader social change as well. From supporting bans on smoking in public places to defining disparities in health and health care, research has documented problems related to health and served as foundation for changes in public and professional opinion, health-care delivery, medical education, and public policy.

ADVOCACY FOR THE UNDERSERVED

Advocacy is particularly important for patients from underserved and vulnerable communities because they often face additional social and economic barriers that impede health.4,5,6,7

As discussed in Chapter 1, more than 70% of premature mortality is caused by behavioral, social, and environmental factors, including housing conditions, food availability, and access to health care.8 The ability to influence these social factors (e.g., choosing to live in a safer neighborhood or finding a higher paying job) is a function of the power to change one’s circumstances. Those living in marginalized and underserved communities are not only more likely to be sick but also less likely to be able to change the conditions that make them sick. For example, those living in homes exposed to toxic chemicals from a local oil refinery—like Michael in the opening case study—may have few options to relocate.

BARRIERS TO ADVOCACY

Since social factors can contribute to poor health status and be barriers to following through with therapeutic plans, provider advocacy activities directed at upstream social and environmental factors could play a significant role in shaping health and illness. While health professionals working in underserved settings typically recognize the importance of community advocacy, there are a range of obstacles that can prevent them from engaging on the population level.

According to a physician survey conducted by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, four out of five physicians think patients’ social conditions are as important to address as medical issues.9 However, according to the same study, a similar number reported that they did not feel confident in addressing the social needs of their patients.

Another study reveals that more than 90% of physicians surveyed believe that public roles are important and over three quarters of providers believe it is very important to be involved in issues connected to patients’ health, including issues such as tobacco control, road safety, and poor nutrition. Nevertheless, most of the providers surveyed were not involved with local community or medical organizations or political issues related to health.10

Moreover, compared with the general public, physicians are less likely to exercise their right to vote, a potential indicator of community engagement.11 Voting is a fundamental way to contribute to community decision making, including on health-related initiatives such as a tobacco tax. There are few data explaining why, as a group, health-care providers show low levels of civic engagement. Proposed reasons include not feeling competent to address issues outside of clearly defined clinical problems and a lack of time.12 When physicians do feel that they are “experts” in a field, however, there is evidence that they are often involved in policy discussions. In one survey of academic physicians, over half of those who responded reported that they were engaged in at least one of three types of policy-related activities: policy-related research, expert advice to government officials, and collaboration with organizations to advocate for public policy.13

Although it is generally conceded that health professionals have the authority to shed light on matters influencing health granted to them by their intimate contact with patients, some question whether this authority translates into an obligation.1 Even in very concrete ways, like caring for patients from underserved communities, the obligation to engage in wider social issues is not universally accepted by medical professionals. Over 30% of US physicians, for example, do not accept patients covered under Medicaid, the insurance for the poor.14 Furthermore, the role and responsibilities of the individual provider are often contrasted with that of the medical profession as a whole, with advocacy toward patients (the agency described earlier), falling under the responsibilities universally acknowledged of the individual provider, and “activism” toward changing social causes of disease as a responsibility of the profession.1

As a profession, much of medical advocacy has been focused on self-interested issues rather than on larger societal ones. Lobbying for issues benefiting medical providers (i.e., better reimbursement, fewer regulations) are often framed, appropriately or not, in terms of patient care, safety, and outcomes. Physicians in politics, with some notable exceptions (e.g., Chile’s Michele Bachelet) have often done more to protect the privileges of their social class than advocate for the needs of the vulnerable, advocating for policies that cut funding to the social safety net and oppose universal health insurance, for example.15

Despite a lack of confidence in their ability to effect change in broader community issues and a spotty history of doing so, health-care professionals are uniquely positioned to engage in community advocacy. In addition to their unique vantage point, health-care professionals continue to enjoy a high level of trust among Americans. In a recent national poll, nurses, pharmacists, and physicians comprised three of the four top-ranked professions for honesty and ethical standards.16 As trusted leaders in the community, health professionals have an opportunity to advocate for change and are regarded as highly valued partners by community advocacy groups.

Common Pitfalls

Health professionals may fail to recognize the broader social and environmental factors that make patients sick.

Health professionals often feel ill equipped to address nonclinical factors that contribute to patients’ health.

Health professionals are less likely to engage with health-related issues at the community level, such as through civic engagement and working with community organizations.

Health-care providers have been more engaged in efforts for self-interested gains than in broader social issues.

Many health-care providers define their public role narrowly.

Broader social activism is considered a responsibility of the profession rather than the individual provider.

The staff at Michael’s clinic is astounded at the number of patients they see with asthma. They establish a special asthma clinic, an asthma nursing hotline and a program to visit and assess environmental asthma triggers in patient homes. They document all the hospitalizations for asthma from their clinic. The clinic contributes data to the department of public health and providers join efforts to advocate for higher standards of pollution control. Comparing these rates with the lower rates of hospitalizations for asthma in more affluent areas and using Michael’s daughter’s multiple visits to the hospital as an illustration, one nurse writes a letter to the editor of a local paper.

COMMUNITY ADVOCACY ACTION STEPS

Community advocacy begins when an unresolved problem requiring intervention beyond the scope of typical practice is identified in the course of patient care. Examples abound of health professionals who noticed a problem among patients who they served and “connected the dots” to advocate for changes at the community level to address the underlying behavioral, social, and environmental determinants of these problems. Research and data collection is often the place many health-care advocates begin, but their efforts to improve health should not end there. Dr. Abraham Jacobi, regarded as the father of pediatrics in the United States for his pioneering advocacy for child health in the latter part of the 19th century, witnessed the ill effects of malnutrition and the consumption of unpasteurized milk on children in his practice. He became an outspoken promoter of breastfeeding and one of the first to advocate that raw milk is safer to drink after boiling.17,18

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree