Affect and Psychopathology

“What a battle a man must fight everywhere to maintain his standing army of thoughts, and march with them in orderly array through the always hostile country! How many enemies there are to sane thinking! Every soldier has succumbed to them before he enlists for those other battles.”

— Henry David Thoreau

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

The reader will be able to:

Describe the drive theories of anxiety and psychopathology.

Describe the ego psychological theories of emotional and behavioral pathology.

Describe the object relations theories of affective disorders and psychopathology.

Describe the self psychological approach to affective and behavioral disturbances.

THEORY, AFFECT, AND PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

The preceding chapters have outlined the major philosophies of the structures and functions of the mind and their normal development. Each scheme describes a complicated system with multiple opportunities for processes to go awry. Since the major

psychologies were derived from clinical practice, and since clinicians only become involved when things go wrong, each school of thought takes its own approach to the genesis and nature of psychopathology. Each school’s view of normal development and function is intimately linked to its view of how things go amiss.

psychologies were derived from clinical practice, and since clinicians only become involved when things go wrong, each school of thought takes its own approach to the genesis and nature of psychopathology. Each school’s view of normal development and function is intimately linked to its view of how things go amiss.

Moods, of course, are a vital part of normal mental life. Emotions color our individual worlds and add a special dimension to experience. In clinical practice, however, and in the theories that underlie it, emotions are considered a special case of psychopathology, stemming from the same roots as disorders of thought, perception, and behavior. (Perhaps it is for this reason that most of the literature uses the term “affect” to describe what is more precisely identified as “mood,” or, in everyday language, “emotion.”) Therefore our review of psychopathology will incorporate each theory’s view of emotional states.

DRIVE PSYCHOLOGY

The original topographic model of drive psychology generated a schema of psychopathology that was as mechanical as the underlying theory itself and was of severely limited clinical applicability. From about 1885 to 1897, the focus was on the so-called “actual neuroses,” namely neurasthenia and anxiety neuroses. In certain individuals who had been rendered neuropathic by congenital or hereditary predisposition, unhygienic sexual practices produced symptoms directly. Excessive masturbation or nocturnal emissions yielded neurasthenia, a condition marked by lassitude, fatigue, and somatic symptoms such as headache and dyspepsia. Sexual frustration or sexual activity that did not result in gratification produced anxiety neuroses, marked by persistent anxiety punctuated by anxiety attacks.

This model of “dammed-up libido” lacked enough explanatory capacity to survive without substantial modification. As psychoanalysts became more attentive to the nature and workings of the drives, a second model emerged and held sway from about 1897 to 1923. Energy was the domain of the drives, not of the affect itself. Emotions were now considered to be drive derivatives, and psychopathology was the result of conflicts originating from the drives. The classical formulation of hysteria formed the bedrock of psychoanalytic explanation of behavioral pathology.

Freud and Josef Breuer examined and treated a number of patients with “hysteria,” i.e., symptoms of muscular or sensory impairment not traceable to any somatic cause. Drawing on the work of Jean Martin Charcot and Pierre Janet in Paris, they at first hypnotized their hysterical patients and discovered emotional conflicts that were being symbolically represented in the hysterical symptoms. For example, in the case of “Fraulein Elizabeth von R.,” the patient’s younger sister became sick during her pregnancy. Fraulein von R. went for a walk with her sister’s husband. Returning home a few days later, she awoke with unexplained pain and weakness in her legs. Under hypnosis, it became evident that she desired her brother-in-law but of course could not acknowledge this forbidden attraction. In the topographic model of the time, her desire was suppressed, and her guilt was manifest as pain and weakness in the very legs that took her on the walk. Hypnosis soon proved unnecessary as Freud and Breuer found patients could recall “forgotten” events when fully awake, and the other cases they studied supported the same formula:

An unacceptable emotion stems from the drives. It cannot be experienced in the system Cs (conscious), so it is relegated to the system UCs (unconscious). Since there is no avenue for direct resolution of the conflicted emotional state, the energy deriving from the drive is manifest in physical symptoms, usually symbolically representative of the conflict itself.

Hysteria, obsessions, and phobias all shared the same formula and were classified together as the defense neuropsychoses. Obsessions represented attachments to symbolic displacements of the objects of earlier psychosexual stages (oral, anal, phallic); phobias embodied the overwhelming fear of such objects, similarly displaced into contemporary symbols.

This revolutionary formulation, elegant for its time and context, begged questions: What is the mechanism that diverts emotion and its energy from conscious to unconscious? How is that energy converted to the observed symptoms? In what part of the mental apparatus is emotion contained? The reader may now see how the accumulation of more clinical experience pushed the model past its limits and forced these questions. In yet another creative leap, Freud produced the structural model, as described in Chapter 1, which addressed these difficulties and expanded the horizon of psychodynamic explanation of psychopathology.

The structural model, introduced in 1923, postulated the presence of id, ego, and superego, allowing the fundamental problems of the topographic model of psychopathology to be addressed. At its most basic, the structural formulation of psychopathology maintains:

Drive impulses originate in the id.

As the affects and behavior deriving from these impulses press upon awareness, superego rejects some of them and ego is threatened by their power. The battle among the structures is the essence of psychological conflict.

Ego erects various defensive strategies to contain or divert these undesirable impulses. Most, if not all, of this defensive containment happens unconsciously. Most of the mechanisms employed would be considered irrational by the conscious ego.

The end result of these defensive distortions of id impulses and drive derivatives is a panoply of symptoms, cognitive, emotional, and/or behavioral.

Thus Fraulein von R.’s circumstances could be more fully explicated: Her desire for her brother-in-law, originating in libidinal id impulses, was rejected by her superego even before it ever reached conscious awareness. Ego contained it first by repression, which only worked temporarily. As the urges persisted just beyond awareness, ego was forced to redirect the libidinal energy through symbolic representation in somatic symptoms.

The expansion of drive theory to include a conflict model allowed psychoanalysis to address many more dimensions of psychopathology, including affect. For Freud and his followers, the primary emotion was anxiety; all others were modifications, displacements, or substitutions. The model of anxiety based in structural theory held that anxiety of one sort is the inevitable result when the influx of energy from any stimulus is greater than what the individual can master. This type of anxiety was labeled traumatic anxiety; birth was the prototype for such a stimulus. The growing infant experiences similar sorts of automatic anxiety when he or she is hungry or in pain. Because the ego is still immature, this reflex form of anxiety is almost the only entity in the infant’s affective repertoire.

Later, the ego gains the capacity for memory and can connect traumatic, anxiety-provoking events to their surroundings. The infant notices that he or she only gets hungry in the absence of

mother; that the dog barks and causes fear. The young ego associates the departure of mother or the presence of the dog with sensations of anxiety and develops the capacity for signal anxiety. Even though there is nothing inherently traumatic about the presence of the dog or the absence of the mother, the child has come to associate those signal events with impending anxiety.

mother; that the dog barks and causes fear. The young ego associates the departure of mother or the presence of the dog with sensations of anxiety and develops the capacity for signal anxiety. Even though there is nothing inherently traumatic about the presence of the dog or the absence of the mother, the child has come to associate those signal events with impending anxiety.

Signal anxiety in the more mature ego can deal similarly with internal stimuli, those stemming from unacceptable id impulses. In the presence of a forbidden love object, the wishes of unrestrained libido would be intolerable. The experience of signal anxiety when he or she approaches is weaker and much more manageable. Additionally, it allows the ego to prepare an array of defenses to contain and manage the drive derivatives.

The first and most indispensable tool of the ego in managing anxiety is the defense mechanism of repression. Unacceptable impulses are unconsciously extruded from the ego and returned to the id. But with the impulses goes all their associated energy; so when ego engages in repression, it feeds some of its energy to the id, which then presses its desires all the more powerfully. Too much repression, therefore, promotes the emergence of emotional, cognitive, and/or behavioral pathology. This constellation was named anxiety neurosis. Collectively, the earlier-defined defense neuropsychoses (hysteria, obsessions, and phobias) and anxiety neurosis were now labeled as the psychoneuroses.

MR. BROWN acts out a typical “success neurosis.” He first identifies with father and attempts to achieve both interpersonal sexual success and external business success. Either achievement would echo the original Oedipal situation; and just on the brink of this success, Oedipal guilt emerges, and he fears the consequence in the form of castration anxiety. As a result, his superego must defeat his id aims rather than allow ego to achieve his goal and put him at risk for retribution.

MR. BROWN acts out a typical “success neurosis.” He first identifies with father and attempts to achieve both interpersonal sexual success and external business success. Either achievement would echo the original Oedipal situation; and just on the brink of this success, Oedipal guilt emerges, and he fears the consequence in the form of castration anxiety. As a result, his superego must defeat his id aims rather than allow ego to achieve his goal and put him at risk for retribution.Paranoia

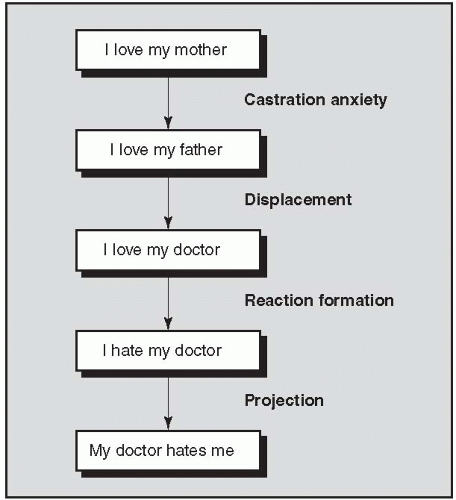

An early example of the application of this model is in Freud’s view of paranoia, drawn from the case of a patient, Daniel S., who maintained a fixed and unshakable belief that his prior psychiatrist was engaged in a plot to change him into woman and abuse him. From his own associations and memories, Daniel painted a picture of a sadistic father who engaged in some very unusual methods of disciplining him. Fearing castration if his father should ever discover

his Oedipal urges, Daniel defensively retreated to his father as a love object. This homosexual solution was utterly unacceptable to Daniel’s superego and became securely repressed. The intimate relationship with the prior psychiatrist fanned the flames of this desire within his id. He had to deny his love and substitute an imagined hate. That hate for a figure of authority, however, evoked the same fears as Daniel’s youthful castration anxiety and led to projection of that hate onto the psychiatrist. (See Figure 7-1.)

his Oedipal urges, Daniel defensively retreated to his father as a love object. This homosexual solution was utterly unacceptable to Daniel’s superego and became securely repressed. The intimate relationship with the prior psychiatrist fanned the flames of this desire within his id. He had to deny his love and substitute an imagined hate. That hate for a figure of authority, however, evoked the same fears as Daniel’s youthful castration anxiety and led to projection of that hate onto the psychiatrist. (See Figure 7-1.)

As much as this solution put Daniel in jeopardy, it was a preferable compromise to the conscious awareness of his repressed homosexual desires. All other psychopathology mimics, usually with lesser severity, this substitution of a set of psychoneurotic symptoms for conscious awareness of an unacceptable id impulse.

Depression

While Freud focused almost exclusively on anxiety as the primary pathological emotional state, he made a major contribution to the understanding of depression in his 1905 paper, “Mourning and

Melancholia.” Mourning he defined as the state of experience in which a person has lost a significant love object or abstract representation of such an object and feels sadness about the loss. The emotion is entirely conscious, as is the awareness of the loss, although its meaning may be hidden in the unconscious. (For example, a person who has lost a job may not immediately recognize that the job represents a feeling of potency in the world or a potential source of parental approval. But he or she is consciously aware of feeling sad and consciously connects the sadness to the job loss.)

Melancholia.” Mourning he defined as the state of experience in which a person has lost a significant love object or abstract representation of such an object and feels sadness about the loss. The emotion is entirely conscious, as is the awareness of the loss, although its meaning may be hidden in the unconscious. (For example, a person who has lost a job may not immediately recognize that the job represents a feeling of potency in the world or a potential source of parental approval. But he or she is consciously aware of feeling sad and consciously connects the sadness to the job loss.)

Melancholia, by contrast, is a much more deep-seated sense of despair, often marked by apathy and pessimism. The object of the sadness may be entirely unavailable to awareness, or the identified loss may be utterly insufficient to justify the degree of distress. In such cases, Freud usually found that there was an unconscious perception of loss of something within the self. The link between the stimulus and the emotional response was suppressed, as was the symbolic significance that linked them. (For example, a woman who strongly but unconsciously identified her boss with her father, and made him the object of unconscious libidinal wishes, might become seriously depressed after the economy forced the company to let her go.) Self-reproach directed toward the representation of that object within the ego is as typical as anger is at the lost object. People who have suffered repeated or intense early losses may be more vulnerable to experiencing this type of depression when other losses occur in adult life. Those with particularly harsh superegos are more susceptible to self-criticism.

Even after a century, the formulation retains validity: Mourning (or grief or bereavement) is a conscious state of sadness linked by the patient to a specific external loss. Melancholia (depression proper in contemporary terminology) is a more profound state of despair in which the loss is perceived as being within the self, and the links are mostly unconscious.

Character Traits

While drive psychology never addressed what are now defined as personality disorders, Freud’s followers, particularly Karl Abraham (1877-1925) elucidated character types that represented a persistent, background form of psychopathology. As described in Chapter 1, normal psychosexual development proceeds through

stages: oral (first year), anal (1-3 years old), and phallic (3-5 years old). Each entails its own developmental demands. Failure to cope with the demands of any phase can result in fixation, an inability to move beyond the characteristics of that stage; stress or stimulus beyond ego’s capacity to cope at later points in life can lead to regression, a return to an earlier developmental level.

stages: oral (first year), anal (1-3 years old), and phallic (3-5 years old). Each entails its own developmental demands. Failure to cope with the demands of any phase can result in fixation, an inability to move beyond the characteristics of that stage; stress or stimulus beyond ego’s capacity to cope at later points in life can lead to regression, a return to an earlier developmental level.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree