Aggression in Children: An Integrative Approach

Joseph C. Blader

Peter S. Jensen

Introduction

Aggressive and Prosocial Behavior

A central goal of every human community is the mitigation of aggression between its members. The seventeenth century English philosophers who articulated today’s Western concepts of liberty and democracy considered the restraint of unsanctioned aggressive behavior the only justification for the state to intrude on personal freedom (1,2). Hobbes wrote about the necessity of a “common power to keep them all in awe.” That power (i.e., the state) exists to constrain the antagonisms that flow from three drives: 1) to acquire resources, 2) to protect those resources and personal safety, and 3) to enhance and defend one’s prestige. He memorably portrayed the downside of the perpetual conflict that would otherwise result (1):

In such condition there is no place for Industry because the fruit thereof is uncertain … no commodious Building; … no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short.

When Charles Darwin considered these issues within a biological framework some 200 years later, these predecessors who depicted life as a struggle for existence influenced his work (3). Natural selection involves competition for the resources that are essential to survival and successful reproduction. Scarcity of these resources means that some creatures inevitably deprive others within their species of access to them, often through aggressive behavior. However, Darwin also devoted much attention to the adaptive benefits of the “social instincts,” such as sympathy, cooperation, altruism, and the desire to maintain the approval of one’s group, which exert an equally natural countervailing force on intraspecific aggression. After all, when danger is at hand humans tend to seek safety in one another’s company. Potential procreative partners may also favor these prosocial characteristics, which would hasten their proliferation through the process of sexual selection (4).

As man is a social animal, it is almost certain that he would inherit a tendency to be faithful to his comrades, and obedient to the leader of his tribe; for these qualities are common to most social animals. He would consequently possess some capacity for self-command. He would from an inherited tendency be willing to defend, in concert with others, his fellow men; and would be ready to aid them in any way, which did not too greatly interfere with his own welfare or his own strong desires (5).

Since then, behavioral research has supported the overall view that a combination of affective, cognitive, and social factors disincline the majority of people from harming others most of the time (6,7). We also know a fair amount about when these factors could lose their potency to inhibit aggressive behavior. For instance, aggressive behavior becomes more likely when one perceives that a potential target belongs to a different social grouping; when one believes that another person unjustifiably threatens his or her prerogatives and well being; when one believes that others will approve of or encourage aggressive acts; and when one believes that the benefits of aggression will exceed its probable cost.

Under normal circumstances, then, human interaction has a default value of relative congeniality. Numerous affective, social-cognitive and experiential factors, however, can tip the balance toward disharmony. In effect, then, most peacekeeping and law enforcement activities do not depend entirely on the external displays of might that Hobbes wrote about, but rather seem to take place chiefly within the human skull.

Consequently, many psychiatric conditions have aggressive behavior as a major complication. High negative emotionality may predispose to a low threshold for anger or frustration, so that one reacts forcefully to situations others would find only mildly bothersome. Distorted cognitive processes may lead to unwarranted alarm about environmental threats, to feeling impelled by some force to hurt others, or to erroneous beliefs about entitlement to impose one’s will on others. High anxiety may trigger avoidance or escape behaviors that can injure others who get in the way. Inadequate impulse control can disrupt response selection so that aggression has precedence over alternatives. Abnormal development may impair the acquisition of coping behaviors and self-regulatory capabilities that ordinarily suppress dyscontrolled outbursts. In addition, some highly prevalent diagnoses have aggressive behavior as a cardinal feature, such as conduct disorder, antisocial personality disorder, or intermittent explosive disorder.

Certain experiential factors can contribute to persistent aggression and therefore have psychiatric significance. Early severe maltreatment may disrupt the development of empathy. Socialization that promotes violence and threats as vehicles for self-preservation may lead to aggression that persists even in new social contexts that disapprove of such behavior.

Persistent aggressive behavior most often originates in childhood. In particular, aggressive behavior among school-age children confers high risk for unfavorable outcomes not just during youth but also throughout later life (8,9,10). Aggressive dyscontrol is also the concern that most often motivates families to obtain mental health care for their preadolescent children. Nevertheless, aggressive behavior still eludes consistently effective intervention. The combined force of troubling outcomes, adverse community impact, high prevalence, and uncertain treatment prospects propels childhood-onset aggression to the forefront of challenges in mental health today.

Aggression and Victimization Among Youth

Community-Based and Clinically Based Estimates

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies both indicate that physically aggressive behavior among preschoolers is common but diminishes upon school entry and during the elementary school years. Tremblay and colleagues (11) found that only a minority (28%) of 3-year-olds were said to display little or no aggression. Parents of 27% of 3-year-old boys report their child “hits, pushes, or trips” others at least “sometimes” (12). The comparable rate for girls is 19%. Parents reported “modest aggression” was reported for 58%, with equal gender representation (11). Parents reported quite high aggressive behavior among 14%, of whom 57% were male.

In elementary school samples, larger gender differences emerge for “starts fights,” with parent reports indicating that fighting is present among about 12% of boys and 6% of girls (13). However, the prevalence of “bullies, threatens, or intimidates” are relatively similar between genders (boys 13%, girls 10%).

Several longitudinal studies have tracked teacher-reported conduct problems through elementary school. Some also had initial assessments from infancy and some had followups through young adulthood. Data from six of these studies found that 8% of boys consistently obtain the highest physical aggression ratings time after time (14). Estimates may be biased toward the higher end, since two of the samples sought to recruit a high-risk cohort. The finding that children appear to show considerable stability in how teachers rate their aggressive behavior across many school years is even more striking than the continuity of parent report, because teachers and classmates change annually for most children. There is also a subgroup representing 10% of girls who also have high, stable levels of physical aggression, though overall severity is lower than that for the boys.

Aggressive behavior, regardless of diagnostic context, is among the most prevalent chief complaints for youth seen in inpatient, outpatient, and residential treatment services (15,16,17,18,19). Among preadolescents, aggressive dyscontrol may be the most frequent reason for treatment in specialty mental health services. By adolescence, rising prevalence of mood disorders and self-injurious behavior, particularly among females, eclipses aggressive behavior as a chief complaint. However, new-onset aggressive behavior among girls in early to middle adolescence seems rather frequent, and in clinical samples may be an associated feature of mood disorders (20). Therefore, despite a shift from “externalizing” to “internalizing” diagnoses with age, aggression may remain as a formidable cotraveller.

The majority of youngsters who fight seem to do so in some settings and not others. Aggressive behavior at home only is especially common: About half of boys who fight show physical aggression within the family exclusively. Only 20% were reported to display physical aggression at both home and school (21).

Crime and Victimization Surveys

Violent crime among juveniles in the United States crested in 1995, and declined steadily until at least 2003 (22). Nevertheless, adolescence remains a dangerous period of life in the United States. Those 12 to 15 years old experienced assaults at a rate of 45.3 per 1,000 during 2003, and the rate for 16- to 19-year-olds was slightly higher, 46.6 per 1,000. Violent victimization decreases with age, dropping by 24% among 20- to 24-year-olds (35.5 per 1,000), with a further 33% decline among those 25 to 34 years of age (22.3 per 1,000). Other youth were most often the perpetrators.

Victims aged 12 to 20 identified their assailant as under 20 in 73.6% of crimes. Overall, 30% percent of victims of all ages in 2003 identified the offender as between the ages of 12 and 20 (23).

Violence among youth is more likely to be a group phenomenon than that perpetrated by adults. In 2003, 54% of violent crimes by juveniles involved more than one assailant (22). During the same period, far fewer of those by adults (18% to 22%) involved multiple offenders (23).

The period between the end of the school day and early evening is the time of greatest risk for youth-on-youth violence during school days. On nonschool days, timing of violent crime better resembles the adult-offender pattern: Incidents gradually ascend to their peak numbers at 11PM, then decline until 6 AM, when they begin to rise again (22).

Approaches to Characterizing and Subtyping Aggression

By Motivation

There is a long tradition of distinguishing aggressive behavior by whether an act’s motivation is mainly a) to repel a perceived threat or annoyance, or b) to acquire something desirable. The former often defines affective, frustrative, impulsive, or defensive aggression. The latter is associated with terms like proactive or instrumental aggression. In general, psychometric and psychobiological evidence supports such a distinction between these behaviors. As an approach to categorizing people, rather than behaviors, it may have some shortcomings, since many individuals display aggressive behaviors characteristic of both types at various times (24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32).

Impulsive, Affective, or Reactive Aggression

Affective or impulsive aggression refers to dyscontrolled reactions, which have the potential or the intent to hurt others, that occur upon exposure to events perceived as noxious. The provocations are usually things that one might agree are annoyances but within a level of intensity that most other children handle with composure. Triggers may appear quite trivial, such as not getting the right cereal for breakfast. Directions to comply with an adult request or the need to end a preferred activity to transition to something else are very frequent antecedents to full-blown rage episodes. Hitting, kicking, destruction of property, and self-abusive behavior are common. A verbal onslaught of screaming, vulgarity, threats, and hurtful insults often provides soundtrack. Since the behavior is most often reactive and nearly instantaneous, it tends to be overt and unplanned. These events can also show a self-defeating character. That is, youngsters in their explosive rage may end up hurting themselves by, for instance, punching walls or glass, damaging their own prized possessions, or escalating when it is obvious, or should be, that doing so only worsens their plight. They may go after people much larger and stronger than themselves. A few children do regain composure when placated, but it is also common for these outbursts, once kindled, to have to run their course before the child regains control. The onset of these difficulties is most often in early childhood, especially among boys, and their risk for persistence into adulthood is great (11,33,34).

Proactive, Instrumental, or Appetitive Aggression

Proactive or instrumental aggression includes assaultive or coercive behavior purposefully used to achieve a goal such as material goods or social status. Willful property destruction is also included by some. Descriptions of proactive/instrumental aggression sometimes liken it to hunting, but for many species predation and intraspecific aggression have quite different underpinnings and phenomenology (35). A few features of proactive aggression make plain that the actor is in control. For instance, proactive aggression stops once the goal is achieved or when it becomes clear that it has become unobtainable. Victims are chosen to make success likely. The aggressor may take protective measures to avoid getting hurt and evasive action to avoid apprehension. While planning and premeditation are certainly consistent with proactive aggressive behavior, it is probably not a requirement. A number of “acquisitive” violent acts, such as certain robberies and sexual assaults, are often opportunistic and not necessarily performed with much forethought.

Among youth whose aggressive behavior is principally of the proactive/instrumental type, we can also discriminate two important subgroups.

Adolescent-Onset, Peer-Facilitated Proactive Aggression

First, a group of proactively aggressive youth show adolescent onset of antisocial behavior. Aggressive acts in this context are on the whole less violent, rely on peer encouragement, and seem likely to diminish by adulthood (33,36). This pattern of antisocial behavior seems practically normative in many Western countries (33), and social mores and penal codes have been relatively tolerant of the milder transgressions. However, the boundary between obnoxious pranksterism and major violations that cause serious injury or damage is fortified by common sense and restraint. The group dynamics of adolescents behaving recklessly do not promote these qualities, often with tragic results. In these situations, a young person may become ensnared by the consequences of delinquent participation. School expulsion, increased wariness of other peers, and involvement with law enforcement or correctional facilities can promote further identification and involvement with delinquent peers, and deflect what had hitherto been a pathway of overall positive adjustment.

Callous-Unemotional (“Psychopathic”) Proactive Aggression

Another important subgroup of proactively aggressive youth is profoundly indifferent to the consequences that their misbehavior has upon others. Displays of genuine remorse are rare, and a current descriptor for this group’s salient personality features, “callous-unemotional traits,” is highly evocative of their lack of empathy, self-centeredness, and shallowness (37). If we can consider eruptive, volatile reactive aggression as “hotheaded,” we might regard this conduct, by contrast, as “coldhearted.” These youth are responsible for a large number of violent offenses, their aggressive behavior is often persistent, and development of these characteristics may be early in childhood (28,37,38,39,40).

This description bears obvious similarity to some affective features of psychopathic or sociopathic personality, which has been a topic of study in adult criminology and personality psychology for many years, and more recently, a topic of some interest in cognitive and affective neuroscience (41,42,43).

As it happens, though, a great many individuals exhibit both the angry overreactivity of affective/impulsive aggression and the deliberate, calculated injury to others characteristic of psychopathy. Indeed, some definitions of psychopathy include both impulsive hotheadedness along with the capacity to trample calmly upon the rights of others when it suits the purpose. A majority of aggressive individuals, in both clinical and forensic settings, seem best typified by the affective/impulsive designation. The next largest group comprises a mixed group, and least common are aggressive psychopathic individuals who are not especially impulsive or volatile. Indeed, it has been suggested that some of the latter group may be quite capable of channeling their calm fearlessness and ambition to aggrandize themselves in more socially acceptable ways.

There are interesting findings bearing on possible neuroaffective and neurocognitive substrates of psychopathy. However, the significant overlap between psychopathy’s steely emotionality with impulsivity, cognitive or learning deficits, low frustration tolerance, etc. precludes clear interpretation of many studies that compare psychopathic individuals with normal controls. Nonetheless, one rather consistent finding is that psychopathic individuals show significantly less emotional arousal in experimental paradigms that ordinarily elicit differential cognitive, autonomic or CNS responses to neutral or emotionally laden stimuli (29,42,44,45,46,47). Classic and recent studies of psychopathic adults also found they were more tolerant of pain and less conditionable (45) but are rather more sensitive to monetary cues (48).

A robust neuroendocrine finding is that while many impulsively aggressive individuals do not show elevations in prolactin following acute administration of d-fenfluramine (49,50) (a common phenomenon among depressed patients, attributed to reduced sensitivity for the serotonin-stimulating properties of d-fenfluramine that would ordinarily lead to enhanced prolactin release), violent psychopathic individuals show the hyperprolactinemia seen among normal controls (51). On the whole, these data tend to support the value of distinguishing between “dysphoric” aggression and the reward-motivated aggression of those with callous-unemotional traits.

Imperviousness to pain and low conditionability may have etiological significance. One hypothesized process by which people might internalize rules is through the avoidance of unpleasant consequences that might follow transgressions. Low susceptibility to adverse consequences might impair avoidance learning, and thus impede development of the almost instinctual recoil from doing vicious things to others (44,52).

There are very little data on preadolescents that bear on how much additional risk such factors might have on the development and course of aggressive behavior. Parents very often report that aggressive children do not seem to feel guilty (53), but there may be a difference between lack of remorse when one perceives, even incorrectly, that aggression was justifiable retribution, compared to the lack of remorse when one feels entitled to violate the rights of others to satisfy a personal desire. It is also unclear whether affective psychopathic features may develop over time among certain impulsive, labile individuals, perhaps as a result of environmental effects. For instance, one may become inured to punishment and the negative judgment of others when these are meted out in great abundance or inconsistently, and impulsive, difficult behavior certainly increases the likelihood of such interactions with others over lengthy periods. It is also possible that affective/impulsive aggression is indeed reinforced intermittently, increasing the odds that an individual will utilize it in a volitional manner to gain advantage.

By Behavioral Features

Overt/Covert and Destructive/Nondestructive Dimensions

Frick and colleagues (54) reported that specific forms of antisocial behavior tend to aggregate. Put another way, antisocial youngsters seem to display some degree of “specialization.”

Their analysis identified two relatively independent dimensions, which, if dichotomized and crossed, yields quadrants that can categorize most antisocial behavior. One continuum is an overt–covert dimension and the other a destructive–nondestructive dimension. If the destructive dimension roughly corresponds to aggressive behavior, the result is that a certain number of youngsters show mainly overtly aggressive behavior, while another group’s aggressive misconduct is chiefly covert. Overt aggression, as mentioned earlier, is confrontative and may or may not be affectively charged. Covert aggression involves property vandalism, arson, and other damage that may well lead to the physical injury of others in addition to the obvious economic harms. The planning and effort needed to conceal one’s involvement indicates that covert aggressive behavior is volitional.

Their analysis identified two relatively independent dimensions, which, if dichotomized and crossed, yields quadrants that can categorize most antisocial behavior. One continuum is an overt–covert dimension and the other a destructive–nondestructive dimension. If the destructive dimension roughly corresponds to aggressive behavior, the result is that a certain number of youngsters show mainly overtly aggressive behavior, while another group’s aggressive misconduct is chiefly covert. Overt aggression, as mentioned earlier, is confrontative and may or may not be affectively charged. Covert aggression involves property vandalism, arson, and other damage that may well lead to the physical injury of others in addition to the obvious economic harms. The planning and effort needed to conceal one’s involvement indicates that covert aggressive behavior is volitional.

In this framework, overt aggression is motivated largely by interpersonal conflict, anger, or to establish dominance (55). Meanwhile, covert misconduct serves mostly acquisitive purposes, is attended by neutral affect, and is thought to be on the whole less violent, although it is not clear what material gain one derives by gratuitous damage to property.

There is evidence that persistent overt and covert antisocial behaviors have distinct developmental pathways (56). Overt aggressors proceed from minor aggression to fighting to major acts of violence. The covert pathway leads from shoplifting and lying to property damage to fraud and burglary. The implication is that while only a minority progress to the most severe forms of misconduct, those who do had progressed through the earlier stages of the respective pathway.

Direct and Indirect Aggression

In addition to unjustified, injurious behaviors directly applied to a victim or property, another form of interpersonal harm occurs when one seeks to undermine the relationships or social standing of another person. Examples of this so-called indirect, or “relational,” aggression include ostracism and rumor-mongering. This form of antagonistic behavior seems to be most prevalent among girls and young women. Study of this topic has proliferated in social developmental psychology (57) involving mainly community samples, and to a far lesser degree in psychiatry. One obvious reason is that these behaviors are in themselves unlikely to be the chief complaint that leads to clinical referral or criminal justice involvement. The more common scenario in clinical settings is that child patients are the victims of these peer-inflicted adversities. Their attempts at retaliation in kind are prone to backfire, since their lack of social savoir-faire and popularity often leads to poor selections of rumor topics, rebuttals, or audiences. It is therefore unclear how much harm relational aggressors seen in clinical settings actually cause, since effective attacks of this kind seem to require “social capital”— status, credibility, and influence in a peer network (58)— that children seen for mental health care seldom enjoy. Nonetheless, youth whose peers report they display relational and physically aggressive behavior receive teacher ratings of behavioral problems that are somewhat higher than physical-only aggressors (59). Even if relational aggression is not currently on the radar as a strong clinical concern by itself, it seems useful to consider such behavior at least for its usefulness as a marker of impaired peer relationships among youth seen in psychiatric care.

A contemporary wrinkle on this issue is the potential for youth to use the Internet to defame peers with anonymity or even impersonating another individual. Schools take this type of misbehavior very seriously, especially when they include threats, even very oblique ones (e.g., “Better watch out”). School suspensions and requests for mental health consultation have grown for such conduct.

By Longitudinal Course

Setting out to explain how antisocial behavior can show great temporal consistency, while at the same time antisocial behavior is far more prevalent from midadolescence through young adulthood, a highly influential paper by Moffitt (33) distinguished two trajectories of antisocial behavior among youth, both of which include aggressive conduct to differing degrees. Aggressive behavior during the early school years tends to persist and signals a risk for delinquent behavior that continues through adulthood. For a much larger group, antisocial behavior emerges in adolescence, only to show a slow but steady decline by the mid-20s. The former comprises a pattern termed “life-course-persistent,” the latter a trajectory called “adolescence-limited.”

Among early-onset antisocial children, problem behaviors unfold in a fairly well accepted sequence. Early noncompliance, poor rule adherence, and low frustration tolerance are problems at both home and school. While some aggression is common among preschoolers, children whose fighting does not diminish in the early school years are at high risk for persistent violent behavior. As parents themselves, childhood-onset antisocial individuals are more likely to aggress against their offspring and mates, to act irresponsibly, and their behavior or their incarceration burdens their families with hardship.

Adolescence-limited misbehavior, by contrast, usually occurs in a group context and is not pervasive. The earlier discussion about proactive aggression among such “late starters” elaborated on their characteristics. Moffitt suggested that this conduct reflected an antiauthoritarianism derived from frustration over being denied the perquisites of full adulthood despite their physical maturity. However, this group is more likely to sustain productive participation in activities preparatory to adulthood, such as schooling and job training. Delinquent behavior trails off as adulthood finally affords them the opportunity to have the autonomy they craved, but through prosocial means.

Influences on Aggressive Behavior: Psychopathology and Processes

Overview

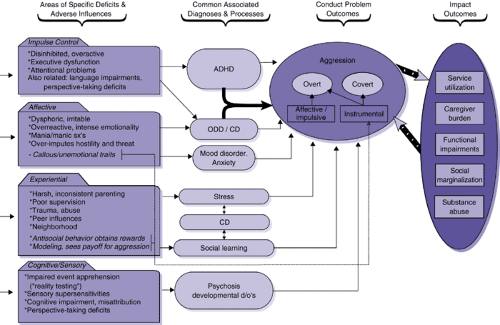

We sort a number of risk factors into four overarching categories, shown in the left portion of Figure 5.2.3.1. Four categories of specific deficits and experiential factors that we distinguish are: impulse control deficits, affective instability, experiences to environments that can promote antisocial behavior, and sensory and cognitive abnormalities. Naturally, one vulnerability can give rise to another, and the linkages on the left acknowledge the interdependence of these factors. To the right are several psychiatric disorders and psychosocial processes from which aggressive behavior often springs, and for which the specific vulnerabilities on the left are diatheses or contributors. Finally, severely disruptive behavior itself has sequelae that can abate (interventions) or increase (social marginalization) persistence and impairments; some of these “impact outcomes” appear on the far right.

The overarching idea is that in high enough titers any of these influences may increase risk for problems with aggressive behavior, but it is more often admixtures of these factors that are pertinent in most clinical situations. In the prototypic case, persistent aggression develops in the context of a wider pattern of chronic disruptive behavior problems, whose chief ingredients are impulse control deficits and affective instability.

Added to these diatheses, experiences can exert a strong moderating influence.

Added to these diatheses, experiences can exert a strong moderating influence.

Impulse Control Deficits

Individuals whose conduct is highly reactive to momentary stimuli and desires often show generalized deficits in their modulation of conduct, cognition, and affect. These deficits are generalized because affected children often show undercontrol of many functions, including self-restraint of conduct and activity level, volitional control over cognition (sustaining attention, problemsolving) and self-regulation of affect, or at least displays of affect. Youngsters whose self-control in these areas deviates markedly from age-typical development usually fulfill diagnostic criteria for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

ADHD is the disorder most frequently comorbid with disruptive behavior disorders, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD), especially before adolescence (60,61,62,63,64,65). Disruptive disorders accompanied by ADHD feature much more aggression and persistence than when ADHD is absent (38,39,66,67,68,69). Children with ODD alone and ODD with ADHD are equally likely to develop CD eventually; however, comorbid youth display this progression much earlier, an onset that predicts worse outcomes, including sustained aggression. Dimensional measures of impulsivity also correlate with aggression and self-harming behavior (24,70). Early hyperactivity predicts subsequent aggression (71,72) and, in tandem with early aggressive conduct problems, strongly predisposes to persistent antisocial behavior (73).

Problems with language development are prevalent among children with ADHD (74,75). In particular, weaknesses in the organization of age-appropriate discourse and the comprehension of more complex language seem common, and differ from the sort of lower level phonological processing difficulties characteristic of reading disabilities (76,77). It is not entirely clear yet if such language difficulties increase the risk for aggression and other conduct problems independent of ADHD. Until more data address this issue, it seems worthwhile to consider that impairments in self-expression plus weak impulse control could make nonaggressive means of conflict resolution more difficult, and that misperceptions of others’ attempts to communicate can contribute to disagreements and misunderstandings of others’ intentions.

Impairments of Mood, Affect Reactivity and Anxiety

“Hotheadedness”

Evidence from several sources implicates affect disturbances in aggression. The correlation between negative affective features (irritability, lability, anger, dysphoria, frustrability) and disruptive behavior is well established (54,80). The correlation between emotional instability and aggression in particular is extremely high among youth (81). Studies of comorbidity substantiate the cooccurrence of disruptive disorders and mood and anxiety disorders (61,63,64,82,83).

One shortcoming of cross-sectional studies of affective features and aggression is lingering uncertainty about which gives rise to which. However, longitudinal studies of temperament

show that persistent negative affect early in life, seen as unconsolability, low adaptability, and irritability, predicts subsequent aggression (84,85). Parental reactions to these difficult characteristics may moderate the ultimate impact of difficult temperament (86,87). From a diagnostic standpoint, longitudinal studies also indicate that early ODD confers heightened risk for adolescent mood disorder (88). This is not a surprising finding because, despite its frequent alignment with conduct disorder, half the symptoms of ODD describe hostility arising from negative affect.

show that persistent negative affect early in life, seen as unconsolability, low adaptability, and irritability, predicts subsequent aggression (84,85). Parental reactions to these difficult characteristics may moderate the ultimate impact of difficult temperament (86,87). From a diagnostic standpoint, longitudinal studies also indicate that early ODD confers heightened risk for adolescent mood disorder (88). This is not a surprising finding because, despite its frequent alignment with conduct disorder, half the symptoms of ODD describe hostility arising from negative affect.

Among youth with conduct problems, those with negative affect symptoms tend to be more aggressive and to experience worse functional outcomes. Unfavorable outcomes include more hospitalizations, police contacts, impaired social relations, substance abuse, and less improvement with treatment (89,90,91,92,93).

As noted earlier, serotonergic functioning in depressed patients and many aggressive individuals without a primary mood disorder shows similar deviations from controls (94). Findings among children have been less consistent, though, and seem moderated by age, family history, degree of irritability, abuse history, and perhaps ethnicity (30,95,96). One recent report indicated that among children with disruptive behavioral problems, those who had normal prolactin elevation to d,l-fenfluramine had fewer conduct problems in adolescence than children who showed the blunted response more typical of depressed patients (50).

Affective disturbances may influence aggression through both abnormalities of sustained mood and more momentary emotional dysregulation. Rageful episodes are common among adults with major mood disorders (97,98). Similarly, irascibility and explosiveness develop often in the context of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Aggressive behavior therefore can arise as a complication of mood and anxiety disorders.

In addition, emotion regulation can be disturbed episodically, with or without persistent problems in prevailing mood, hedonic tone, or anxiety (99,100). Aspects of emotion regulation that are relevant to aggression include high emotional reactivity, poor emotion modulation, lability, and slow recovery from upset (101,102,103). Vulnerability to hot temper has been also associated with possible defects in social information processing, whereby children too readily impute bad intentions to others who may have unintentionally caused some annoyance for them (104). However, depressed children show a similar phenomenon (105), raising the possibility that negative affect distorts appraisals of threat.

Among aggressive children, these features often do not always summate to clear mood disorder diagnoses based on traditional criteria. The result is that similar phenomenology attracts a variety of diagnostic designations. So, prominent lability and irritability that comes and goes may signify a form of mania to some clinicians, while to others the same features manifest emotional impulsivity thought to accompany ADHD. Intermittent explosive disorder strikes others as an appropriate characterization, though outbursts are usually more than intermittent, and interepisode functioning more impaired, than IED usually connotes. Vulnerability to easy emotional upset leads yet others to emphasize inflexibility that can be characteristic of pervasive developmental disorders. And in many settings, the high defensive reactivity that accompanies affective/impulsive aggression suggests sequelae of trauma. All of these can be very accurate and clinically useful characterizations that explain the context in which aggressive behavior emerges, but it is not certain to what extent clinician predilections, in contrast to patient history, inform such decisions. The coming years should bring greater clarity to this topic, accompanied, hopefully, by advances in our basic understanding of how emotion arises, changes, and become perturbed to produce psychiatric illness.

Anxiety

With the possible exception of posttraumatic stress disorder, discussed later, anxiety disorders by themselves seldom increase the liability for aggressive behavior. The situation changes, though, when comorbid conditions enter the picture. Anxious children with ADHD and ODD are more likely to become behaviorally unmanageable, perhaps by virtue of impulse control problems, making it more difficult for them to tolerate anxious discomfort. For instance, efforts to interrupt compulsive rituals for a child with obsessive-compulsive disorder or to enforce school attendance with a child who has separation anxiety can at times provoke aggressive dyscontrol. A frequent comorbidity with anxiety and with ADHD is chronic tic disorders, including Tourette syndrome, a particularly difficult combination that has a high prevalence of rage attacks and destructive behavior (106).

“Coldhearted”

Besides these “hot” affective features, callousness and under emotionality may, as mentioned earlier, influence aggressive behavior used for instrumental goals (38,107). These individuals appear to display rather blunted emotional reactivity to the distress of others, a stimulus that is thought to inhibit gratuitous violence in most people (44). Similarly, the disapproval of others appears to carry little significance for them and it seems they are more interested in asserting control and gaining advantage over others than in companionship. Perhaps as a partial result of this indifference, the antisocial behavior of psychopathic individuals is especially refractory to current treatments.

Environmental Influences

Stress-Related

Diminished Positive Parental Interactions; Harsh and Inconsistent Discipline

Childrearing practices probably affect the development of children’s aggressive behavior through both stress-related and social learning processes; the next section will focus on the latter. It is obvious that children with early onset conduct problems often make difficult housemates, and those with frequent aggressive behavior still more so because family members are the most common targets (108,109,110,111). Even when the behavior is not particularly harmful, many aspects of family life that are normally almost effortless are fraught with the prospect that a meltdown or a “scene” will disrupt otherwise enjoyable activities, draw attention and resources away from siblings, and complicate relations with schools.

The compound effects are to corrode the quality of parent–child relationships, particularly when parents believe misbehavior to be volitional (112). Family stress and discord and frequent repercussions (113,114,115,116) may further degrade a parent’s capacity to apply measured discipline consistently and with composure (87,115,117,118,119). The mutual antagonism that results, and the child’s own unpredictability, may incline a parent toward disengagement or involvement that depends on the parent’s own energy and mood, than on the child’s behavior.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree