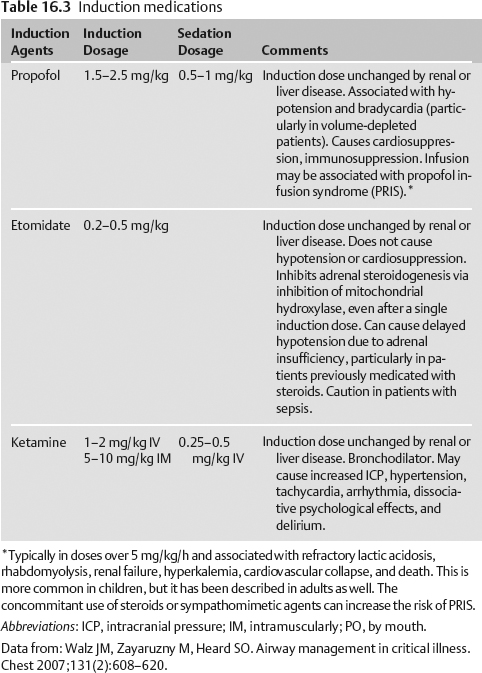

16 Airway Management and Sedation David C. Kramer, Irene Osborn, and Meagen Gaddis When evaluating a neurocritical care patient for intubation, the following considerations must be assessed: (1) urgency of airway management, (2) assessment of ability to secure the airway, (3) issues related to “full stomach” and aspiration risk, (4) intracranial pressure, (5) hemodynamics, and (6) immobilization and restraints as impediments to securing the airway. The basic pharmacokinetics and clinical application of commonly used drugs to facilitate induction, intubation, and sedation will be reviewed. Determine the mechanism of injury and whether there is any associated trauma (craniofacial, thoracic, or pulmonary) or spinal cord injury. If there is a plan for surgery, the patient may need to be intubated for general anesthesia. Assess for previous history of a difficult airway, including a history of prolonged intubation, head or neck radiation or surgery, history of rheumatoid arthritis (associated with atlantoaxial subluxation), Down’s syndrome (associated with abnormal airway anatomy and atlantoaxial subluxation), ankylosing spondylitis (which may limit neck movement), or a history of tracheostomy. A cardiac and pulmonary history should be assessed as well as a history of smoking. A history of last ingestion should be undertaken to ascertain aspiration risk. It is critical to assess for difficulty in securing an airway, which can occur in roughly 10% of intensive care unit (ICU) patients (see H-LEMOON below). Neuro-ICU (NICU) patients have additional risks related to elevated ICP, craniofacial trauma, or cervical spine immobilization. Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ROM, range of motion. The American Society of Anesthesiology has suggested a period of 2 hours after the ingestion of clear liquids, 6 hours after a “light meal,” and 8 hours after a meal of fried or fatty food be utilized as a guideline for surgical patients undergoing elective surgical procedures.1 The administration of 100% oxygen to preoxygenate the patient, avoidance of positive-pressure ventilation during induction, the use of rapid sequence induction (RSI), and the institution of cricoid pressure have been advocated to decrease the risk of aspiration. In the hypovolemic patient who is hypotensive, a bolus of intravenous (IV) fluid is indicated. The judicious use of vasopressor agents may be indicated should hypotension persist. The use of etomidate as an induction agent should be considered in patients who are elderly, critically ill, or have tenuous hemodynamics. Etomidate (even a single dose) can suppress steroidogenesis and cause delayed hypotension after intubation related to relative adrenal insufficiency. The halo device provides the most rigid form of external cervical immobilization and prevents proper positioning for laryngoscopy by restricting atlanto-occipital extension. Oral intubation is often possible, but it is a function of other variables, such as mouth opening, tongue size, upper dentition, and ability to prognath the lower jaw forward. Techniques include awake or sedated fiberoptic intubation and the ILMA performed awake or asleep. Video laryngoscopy may be successful, but it requires expertise, and mask ventilation is often possible with the addition of oral airways. It is imperative that clinicians involved have: (1) skills and equipment for alternative intubation techniques, (2) a neurosurgeon or professional who can safely remove the halo if necessary, and (3) a rescue plan in case of failed ventilation in these challenging patients. Abbreviation: PEEP, positive end expiratory pressure. As part of the preparation for intubation, the cuff of the endotracheal tube (ETT) should be checked and lubricated, the light source on the laryngoscope should be confirmed, contraindications to medications should be reviewed, free-flowing IV access should be present, and blood pressure (BP), O2, and heart rate (HR) continuous monitoring should be applied. In case of hypotension related to induction, the laryngoscopist should have available phenylephrine (mix 10 mg in 250 mL of normal saline (NS), 40 µg/mL; never inject phenylephrine directly from vial without dilution). In patients who are bradycardic and hypotensive, ephedrine is preferred (50 mg in 10 mL; 5 mg/mL).

History and Examination

History

Physical Examination

Neurologic Examination

Differential Diagnosis

Life-Threatening Diagnoses Not to Miss

Diagnostic Evaluation

Less Difficult Airway

More Difficult

History

No history of difficult intubation

History of difficult intubation or tracheostomy

Look externally

Normal face and neck

No facial or cervical pathology

Abnormal facial shape

Facial hair

Overhanging incisors

Narrow mouth

Inability to protrude mandible

Micrognathia

Poor temporomandibular joint mobility

Long, high-arched palate

Facial or cervical pathology

Short, thick neck

Tracheal deviation

Presence of vomitus or blood in oropharynx

Evaluate the 3-3-2 rule

Mouth opening >3 finger breadths (4 cm)

Hyoid-chin distance >3 finger breadths (4 cm)

Thyroid cartilage-mouth of floor <2 finger breadths

Mouth opening <3 finger breadths (4 cm)

Hyoid-chin distance <3 finger breadths (4 cm)

Thyroid cartilage-mouth of floor >2 finger breadths

Mallampati classification (best performed with the patient sitting, tongue protruding, and not phonating)

Class I: Fully visible tonsils, uvula, and soft palate

Class II: Visibility of hard and soft palate and upper portion of the tonsils and uvula

Class III: Soft and hard palate and base of uvula are visible

Class IV: Only hard palate visible

Obstruction and Obesity

No airway obstruction

BMI <30 kg/m2 and/or neck circumference <60 cm

Pathology in or surrounding the upper airway, difficulty swallowing secretions, stridor (ominous and occurs when <10% of airway patent), muffled (hot-potato) voice

BMI >30 kg/m2 and/or neck circumference >60 cm

Neck mobility

Complete flexion and extension of neck

Limited ROM of neck

Presence of halo or neck immobilization devices

History of cervical instrumentation

Treatment

Intubation

Endotracheal tube with a stylet (usually 8.0 in men and 7.0 in women)

Ambu bag with PEEP device attached to 100% O2

Suction

10 mL syringe

Intubating laryngeal mask airway

Capnometer/CO2 detector

Oral and nasal airway

Tape and tincture of benzoin

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree