Anorexia Nervosa

Gerald Russell

Introduction: history of ideas

Two different approaches may be discerned in the conceptualization of anorexia nervosa.

1 The medicoclinical approach defines the illness in terms of its clinical manifestations; the main landmarks were the descriptions by William Gull in 1874(1) and Charles Lasègue in 1873.(2)

2 The sociocultural approach is unlike the more empirical clinical approach and takes causation into account by viewing the illness as a response to prevailing social and cultural systems. This was well argued by the social historian Joan Jacobs Brumberg who considers anorexia nervosa simply as a control of appetite in women responding to widely differing forces which may change during historical times.(3)

There is a strong argument for accepting the original descriptions by Gull and Lasègue as containing the essence of anorexia nervosa. They both recognized a disorder associated with severe emaciation and loss of menstrual periods, inexplicable in terms of recognized physical causes of wasting. They were both extremely cautious about the nature of the mental disorder. Gull spoke of a morbid mental state or ‘mental perversity’, and adopted the more general term anorexia ‘nervosa’ which has persisted until today. Lasègue also referred to ‘mental perversity’ but was bold enough to call the condition ‘anorexie hystérique, faute de mieux’.

It is probably best to seek a balance between the diagnostic rectitude of the medicoclinical approach and the malleability of anorexia nervosa in different sociocultural settings. Looking back in historical times, it may well be that the self-starvation and asceticism of St Catherine of Siena corresponded to modern anorexia nervosa.(4) In more recent times the preoccupations of the patients have altered so that their disturbed experience with their own body(5) or their ‘morbid fear of fatness’(6) has become one of the diagnostic criteria. Yet this concern with body size was not remarked upon by Gull or Lasègue. This is an argument for concluding that at least the psychological content, and perhaps also the form, of anorexia nervosa are changeable in response to historical times and sociocultural influences.

Epidemiology

Screening instruments

The most commonly used screening test in the detection of anorexia nervosa is the Eating Attitudes Test (EAT).(7) Doubt has, however, been expressed about the predictive value of the EAT in the very populations where its use was introduced, as only a small percentage of the EAT-screened positive scores will have an actual eating disorder. Thus, the EAT has limited usefulness in surveys for detecting anorexia nervosa unless it is supplemented by detailed clinical assessments. There is also a risk of failing to detect cases of anorexia nervosa as it was found that patients currently receiving active treatment were among the non-respondents, presumably because they wished to conceal their disorder.(8)

Populations surveyed

(a) General population surveys

These are often impracticable when the aim is to detect anorexia nervosa, a relatively uncommon disorder.

(b) Surveys of primary care populations

A useful compromise is that of surveying populations of patients who consult their general practitioners. A Netherlands study was successful because a large population was surveyed (over 150 000) and the general practitioners themselves, after suitable training, were responsible for making the diagnoses.(9,10)

(c) Populations thought to be more at risk

Surveys of ballet and modelling students were conducted because it was thought likely that there would be a high prevalence of anorexia nervosa among them as a result of pressures exerted to sustain a slim figure in keeping with their professional image.(11,12)

Results of epidemiological surveys

(a) Incidence of anorexia nervosa

The studies which counted only hospitalized patients tended to yield low estimates of the annual incidence of anorexia nervosa expressed per 100 000 population (e.g. 0.45 in Sweden(15)). Estimates based on case registers of psychiatric patients similarly yielded fairly low incidence rates (e.g. 0.64 in Monroe County, New York(15)). The incidence found in community-based studies was by far the highest (7.7 in The Netherlands(10) and 8.2 in Rochester, Minnesota(17)), presumably because they included the less severe cases.

(b) Prevalence of anorexia nervosa in vulnerable populations

A high prevalence rate was found among Canadian ballet students (6.5 per cent) and modelling students (7 per cent).(11) A similar survey in an English ballet school also showed a high prevalence of ‘possible’ cases of anorexia nervosa (7.0 per cent).(12)

Surveys among schoolgirls have shown a fairly wide variation in prevalence rates, ranging from 0 per cent to 1.1 per cent. In the English studies a consistent difference in prevalence rate was found between private schools (1 per cent) and state schools (0-0.2 per cent).(13) This social class distinction was not so definite in the Swedish study where the overall prevalence of 0.84 per cent of schoolgirls, up to and including 15 years of age, represents a high rate for anorexia nervosa.(14)

(c) Age and sex

Epidemiological surveys have confirmed clinical opinion that anorexia nervosa commences most frequently in the young, especially within a few years of puberty. The peak age of onset is 18 years.(13) The illness is less common before puberty, but in a series of patients admitted to a children’s hospital the age of onset ranged from 7.75 to 14.33 years.(18) A prevalence of 2.0 per cent in females aged 18 to 25 was found in a community survey in Padua, Italy.(19)

A marked predominance of females over males is usually reported in surveys, for example 92 per cent in North-east Scotland(15) and 90 per cent among the children in Göteborg.(14) On the other hand a community survey in the province of Ontario gave rise to a more balanced female to male ratio (2:1) when cases of partial anorexia nervosa were included.(20)

(d) Social class and socio-economic status

The view has been widely held that anorexia nervosa occurs predominantly in patients with middle-class backgrounds, since Fenwick’s classical observation that anorexia nervosa ‘is much more common in wealthier classes of society than amongst those who have to procure their bread by daily labour’.(15)

Epidemiological surveys aimed at wider populations leave the question of social class distribution somewhat equivocal. Whereas a high percentage of combined social classes 1 and 2 (Registrar General’s categories) were found in clinical studies,(21) a high social class predominance was not found in studies utilizing case registers.(15) On the other hand, the schoolgirl studies mentioned above tended to confirm a high social class predominance.

Has the incidence of anorexia nervosa increased since the 1950s?

From the 1970s experienced clinicians have expressed their view that anorexia nervosa had increased in frequency. This view gained support from surveys repeated on the same population after intervals of 10 years or more in Sweden, Scotland, Switzerland, and Monroe County, New York.(15) Most investigations found a clear trend for an increased incidence over time although it appears that a plateau was reached in the 1980s.(16) In the most thorough study, from Rochester, Minnesota(17) the increase was confined to female patients aged 15 to 24 years. There were similar findings from the Netherlands with a rise from 56.4 to 109.2 per 100 000 among 15- to 19-year-old females from 1985-1989 to 1995-1999.(10) Although there is support for an increased incidence of anorexia nervosa, there remain dissenting voices.

It is better to pose a different question which renders any controversy unnecessary. We should ask instead whether there has been an increase in the incidence of eating disorders including anorexia nervosa. This is especially relevant in view of the fact that bulimia nervosa is a variant of anorexia nervosa.(22) There is strong evidence that bulimia nervosa is a new disorder and has not simply appeared because of improved medical recognition.(23) Moreover, the incidence of bulimia nervosa has risen sharply at least until the mid 1990s, so that it is now about double that of anorexia nervosa(24) (see also Chapter 4.10.2). In conclusion, it is clear that since the 1960s there has been a significant increase in eating disorders, of which the two clearest syndromes are anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa.

Aetiology

Aetiological concepts

According to one robust opinion, it is essential to pursue the search for a specific and necessary cause of anorexia nervosa because the currently popular ‘multifactorial’ approach has little explanatory power. Accordingly the failure to identify a necessary causal element is regrettable. Many of the factors within a wide range of psychological, social, and physical causes so far studied may therefore only be relevant in predisposing to anorexia nervosa, whose causes still elude clarification’.(25)

The multidimensional approach to anorexia nervosa

It is precisely because we do not know the fundamental (necessary) cause of anorexia nervosa that recourse has to be had to a multidimensional

approach, faute de mieux. Although it has its limitations, a multidimensional approach permits one to consider a range of possible causal factors which not only act in an additive manner but may combine in a specific way to bring about the illness: ‘It is the interaction and timing of these phenomena in a given individual which are necessary for the person to become ill’.(26)

approach, faute de mieux. Although it has its limitations, a multidimensional approach permits one to consider a range of possible causal factors which not only act in an additive manner but may combine in a specific way to bring about the illness: ‘It is the interaction and timing of these phenomena in a given individual which are necessary for the person to become ill’.(26)

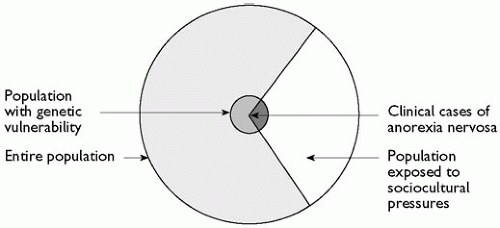

Fig. 4.10.1.1 Diagrammatic illustration of the way that genetic predisposition interacts with sociocultural pressures to cause anorexia nervosa. |

It is useful to provide a simple model of the way that two broad sets of factors may interact and augment each other (Fig. 4.10.1.1). The outer circle represents the entire population in a developed ‘westernized’ country. Within the circle there is a large sector representing females within an age range of 10 to 50 years who experience prevailing social pressures to acquire a slender body shape through dieting. Evidently only a small proportion of these women develop the illness. It is likely that for anorexia nervosa to develop it is also necessary to possess a genetic predisposition, represented by the small inner circle. The intersection of the inner circle and the large sector produces a small sector of females who have the genetic predisposition and also experience sociocultural pressures to lose weight, interacting to cause clinical anorexia nervosa.

Causal factors may not only interact as explained above, but they can also influence the content of the illness, its ‘colouring’, and its form. This modelling function is described by the term ‘pathoplastic’ which was introduced by Birnbaum.(27) Pathoplastic features are to be distinguished from the more fundamental causes of psychiatric illness, but they do exert a predisposing tendency as well as a modelling role.

Sociocultural causes

(a) The cult of thinness

The pathoplastic sociocultural causes of eating disorders have been subsumed under the term ‘the modern cult of thinness’ prevalent in westernized societies.(15) Vulnerable patients are likely to respond to this pressure by experimenting with weight-reducing diets which carry a degree of risk, and anorexia nervosa is arguably but an extension of determined dieting.(28)

It is proposed that the cult of thinness is responsible for the increase in the incidence of eating disorders since the 1950s. The social pressures which lead to dietary restraint include the publication of books and magazines advising weight-reducing diets, the fashion industry which caters mainly for the slimmer figure, television attaching sexual allure and professional success to the possession of a svelte figure, and the emphasis on physical fitness and athleticism.(3)

(b) Changes in the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa

At the beginning of this chapter it was pointed out that the psychological content and the form of anorexia nervosa have changed over historical time and in response to sociocultural influences. Whereas Gull and Lasègue spoke only of ‘anorexia nervosa’ and ‘anorexie hystérique’ respectively, more recent descriptions of the psychopathology of anorexia nervosa have stressed a disturbed experience of one’s own body,(5) a weight ‘phobia’,(29) or a morbid dread of fatness.(6) It is precisely the modern anorectic’s dread of fatness that is most in keeping with today’s cult of thinness. It is arguable therefore that modern societal pressures have determined the patients’ preoccupations and contributed to their food avoidance. These beliefs are held obstinately and amount to overvalued ideas.

(c) Anorexia nervosa as a culture-bound syndrome

The proposition that anorexia nervosa is a culture-bound syndrome has much support.(30,31) An intense fear of becoming obese is as culture bound as the disorder koro (a fear of shrinkage of the genitals) in Malaysia and South China.

A culture-bound syndrome may be defined as a collection of signs and symptoms which is not to be found universally in human populations, but is restricted to a particular culture or group of cultures. Implicit is the view that culture factors play an important role in the genesis of the symptom cluster … (30)

Anorexia nervosa meets these criteria, first because it is limited to westernized or industrialized nations, and secondly because it is clear that the psychosocial pressures on women to become thin constitute a powerful cultural force leading to anorexia nervosa.

In order to allow for exceptions to the rule, when anorexia nervosa occurs in non-westernized countries, the illness may be understood as arising from cultures undergoing rapid cultural change.(31) Anorexia nervosa is thus a ‘culture-change syndrome’, explaining its increased incidence in Japan and Israel. Anorexia nervosa remains rare in Asia (particularly India), the Middle East (with the exception of Israel), and generally in poorly developed countries.

Young female immigrants who move to a new culture may suffer from an increased prevalence of eating disorders. For example, children with anorexia nervosa were found among Asian families living in Britain. This was linked with an exposure to a conflicting set of sociocultural norms in comparison with their parents and grandparents.(32)

Adverse life events

Anorexia nervosa may be precipitated by adverse life events. Early clinical studies depended solely on the patient’s reports of an adverse life event preceding the onset of the illness. These varied widely in severity and included the death of grandparents, a father’s remarriage, a severe physical illness, stress or failure of school examinations, or being teased about being overweight.(21)

Recent studies have relied on more objective measurements of adverse life events and comparisons with control groups. In one such study,(33) life events rated included the death of a close relative, a poor relationship with parents, or an unhappy marriage. Fairly severe life events and lasting difficulties were found in the majority of patients with a late onset (after 25 years), whereas they were only found in a minority of patients with an early onset.

Anorexia nervosa can also be precipitated by sexual experiences and conflicts. In a series of 31 adolescent and young women it was

observed that in 14 first sexual intercourse had occurred before the illness.(34) Sexual problems were seen by 13 patients as major precipitants of their illness; 10 of them had experienced intercourse. The authors concluded that a specific aetiological role of sexual factors seemed unlikely, but there might be a direct relationship between the onset of eating difficulties and concurrent sexual problems.

observed that in 14 first sexual intercourse had occurred before the illness.(34) Sexual problems were seen by 13 patients as major precipitants of their illness; 10 of them had experienced intercourse. The authors concluded that a specific aetiological role of sexual factors seemed unlikely, but there might be a direct relationship between the onset of eating difficulties and concurrent sexual problems.

In a series of 15 patients, anorexia nervosa developed during pregnancy or, more often, during the post-natal period when it was accompanied by depression.(35) Risk factors included ambivalence about motherhood, a large weight gain during the pregnancy, physical complications during pregnancy, post-natal depression, and past psychiatric illness.

Childhood sexual abuse

Since it was reported that a high proportion of patients in a treatment programme for anorexia nervosa gave histories of sexual abuse in childhood, it has been supposed that this trauma would be a contributory causal factor.(36) It would be better if this history could be corroborated, but for obvious reasons it is often difficult to do so. Hence this subject raises unusual difficulties in judging the reliability of the data. Child sexual abuse is also discussed in the chapter on bulimia nervosa (Chapter 4.10.2).

In a careful study of childhood sexual experiences reported by women with anorexia nervosa, the authors classified the events according to the seriousness of the sexual act in childhood and concentrated on sexual experiences with someone at least 5 years older.(37) They found surprisingly high rates (about one-third) of adverse sexual experiences in women with eating disorders, and, unlike other investigators, they did not find that the frequency of these reports was less in anorexia nervosa than bulimia nervosa. They concluded that it was plausible that childhood sexual contact with an adult may in some cases contribute to a later eating disorder.

The complexity of this subject has been increased by a study on the relationship between sexual abuse, disordered personality, and eating disorders.(38) The authors found that 30 per cent of patients referred to an eating disorders clinic gave a history of childhood sexual abuse. In addition, they found that 52 per cent of their patients had a personality disorder. A significantly higher proportion of women with a personality disorder had a history of childhood sexual abuse, compared with those without a personality disorder. Surprisingly they still concluded that in patients with eating disorders it was not possible to show a clear causal link between child sexual abuse and personality disorder.

In a review of the subject a number of hypotheses were examined on the relationship between childhood sexual abuse and eating disorders.(39) One hypothesis is that child sexual abuse is more common in bulimia nervosa than in anorexia nervosa. The authors had to concede that the findings remain inconclusive. They also examined the question of whether child sexual abuse is a specific risk factor for eating disorders. They concluded that this was not the case, as the rates of child sexual abuse in eating disorder patients were similar to or less than those in various other psychiatric comparison groups. Finally, they found strong evidence that patients with eating disorders reporting child sexual abuse were more likely to show general psychiatric symptoms including depression, alcohol problems, or suicidal gestures, as well as an association with personality disorders.

Family factors

Two influential groups of family therapists (Minuchin at the Philadelphia Child Guidance Clinic and Selvini Palazzoli in Milan) have devised family models to explain the genesis of anorexia nervosa.

Minuchin et al. identified faulty patterns of interaction between members of the anorexic patient’s family; they in turn were thought to lead to the child’s attempt to solve the family problems by starving herself:(40) ‘The sick child plays an important role in the family’s pattern of conflict avoidance, and this role is an important source of reinforcement for his symptoms’. Five main characteristics of family interaction were identified as detrimental to the function of the family: enmeshment (a tight web of family relationships with the members appearing to read each other’s minds), overprotectiveness, rigidity, involvement of the sick child in parental conflicts, lack of resolution of conflicts.

Selvini Palazzoli(41) also identified abnormal patterns of communication within these families and in addition described abnormal relationships between the family members. She assumed that anorexia nervosa amounted to a logical adjustment to an illogical interpersonal system.

Bruch(42) described girls who developed anorexia nervosa as ‘good girls’, who previously had a profound desire to please their families to the point of becoming unaware of their own needs. The frequency of broken families in anorexia nervosa is thought to be fairly low. Anorexic families have been found to be closer: the patients more often perceived themselves as having happy relationships within the family.

It remains uncertain whether these abnormal interactions are to blame for the illness or develop as a response by parents faced with a starving child. Careful therapists take pains to reassure parents at the commencement of family therapy: ‘ … we always find it useful to spend some time discussing the nature of the illness, stressing in particular that we do not see the family as the origin of the problem’.(43)

Personality disorders

A sizeable proportion of patients (30 per cent(15) and 32 per cent(21)) were said to have had a ‘normal’ personality during childhood before their illness. Nevertheless there is general agreement of a close relationship between obsessional personalities and the later development of anorexia nervosa. In fact Janet, who carefully described obsessions and psychasthenia, was dubious about the validity of the diagnostic concept of anorexia nervosa. He thought that the patient’s fear of fatness was an elaborate obsessional idea.(44)

In a study of patients admitted for treatment they were classified into anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or a combination of the two disorders.(45) Personality disorders were identified through the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IIIR personality disorders (SCID-II). Seventy-two per cent of the patients met the criteria for at least one personality disorder. Anorectics were found to have a high rate of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder.

There have been attempts to disentangle the features of premorbid personality and illness in order to clarify the personality characteristics predisposing to anorexia nervosa. Women who had recovered from restricting anorexia nervosa were tested at an 8- to 10-year follow-up, using a number of self-report instruments.(46) They were compared with two control groups: normal women and the sisters of the recovered anorexic patients. The women who had

recovered rated higher on risk avoidance and conforming to authority. They also showed a greater degree of self-control and impulse control, and less enterprise and spontaneity.

recovered rated higher on risk avoidance and conforming to authority. They also showed a greater degree of self-control and impulse control, and less enterprise and spontaneity.

Biomedical factors and pathogenesis

(a) Historical notes

Since the early part of the twentieth century a recurring theme has been the possibility that anorexia nervosa is primarily caused by an endocrine or cerebral disturbance. From 1916 there was much preoccupation with the concept of Simmonds’ cachexia,(47) the assumed result of latent disease of the pituitary gland. There was diagnostic confusion between anorexia nervosa and hypopituitarism, which was only clarified much later when it became known that in true hypopituitarism weight loss and emaciation are uncommon. Hormonal deficits indicative of impaired pituitary function are indeed common in anorexia nervosa, but are merely a secondary manifestation of prolonged malnutrition.

Interest in the neuroendocrinology of anorexia nervosa led to the formulation of the hypothalamic model.(6,48) From the beginning the model was aimed at explaining pathogenesis rather than aetiology; it was not considered an alternative to the psychological origin for anorexia nervosa, but a means of explaining a constellation of disturbed neural mechanisms, as follows:

1 a disordered regulation of food intake;

2 a neuroendocrine disorder affecting mainly the hypothalamicanterior pituitary-gonadal axis;

3 a disturbance in the regulation of body temperature.

It was known that these functions all reside within the complex of hypothalamic physiology. A ‘feeding centre’ had been described in the lateral hypothalamus because bilateral lesions there induced self-starvation and death in rats.(49) Over the years it has become clearer that many of the disturbances could be attributed to the patients’ malnutrition, as demonstrated by experimental studies in healthy young women who were asked to follow a weight-reducing diet. It was found that ovarian function is extremely sensitive to even small restrictions of caloric intake which often lead to impaired menstrual function.(50)

(b) Cerebral lesions and disturbances

Interest in the hypothalamic model was fuelled early on by clinical reports of patients diagnosed as suffering from anorexia nervosa who were later found to have cerebral lesions, especially tumours of the hypothalamus. More recently, occult intracranial tumours have been detected, masquerading as anorexia nervosa in young children.(51)

Neuroimaging studies in anorexia nervosa have led to findings suggestive of an atrophy of the brain. CT has disclosed a widening of the cerebral sulci and less frequently an enlargement of the ventricles.(52) The outer cerebrospinal fluid spaces were enlarged markedly in 36 per cent of the patients. When the CT examination was repeated after weight gain 3 months later, the widening of the sulci had disappeared in 42 per cent of the patients who had previously shown this finding. In other patients, however, the widening remained unaltered for 1 year after body weight had returned to normal.

Functional neuroimaging techniques have also been applied to research in anorexia nervosa. Regional cerebral blood flow was measured in three series of children.(53) In the majority of the children there was an above-critical difference in the regional cerebral blood flow most often between the temporal lobes but sometimes affecting other brain regions. Hypoperfusion was found on the left side in about two-thirds of the children. Follow-up scans were undertaken in children after they had returned to normal weight; the reduced regional cerebral blood flow in the temporal lobe persisted on the same side as the initial scan. The authors found that there was a significant association between reduced blood flow and impaired visuospatial ability, impaired complex visual memory, and enhanced information processing.

(c) Genetic causes

As with general psychiatric disorders, genetic and environmental factors are no longer viewed as opposing causes of anorexia nervosa, but rather as interacting with one another. Thus there may be groups of genes that determine risk of the illness and specific environmental situations that elicit or prevent the expression of these genes. There is evidence for a family aggregation of anorexia nervosa. This does not necessarily mean that the origin of the disorder is genetic because environmental factors common to the family must also be considered. In a series of 387 first-degree relatives of 97 probands with anorexia nervosa, it was found that the illness occurred in 4.1 per cent of the first-degree relatives of the anorexic probands, whereas no case was found among relatives of the controls who were probands with a primary major affective disorder, or with various non-affective disorders.(54) The authors concluded that anorexia nervosa was familial with intergenerational transmission. It was roughly eight times more common in female first-degree relatives of anorexic probands than in the general population. The absence in the relatives of probands with major affective disorder indicated the specificity in the risk of transmission of anorexia nervosa and the absence of shared familial liability with affective disorders.

The strongest argument favouring a part-genetic causation of anorexia nervosa is derived from the classical method of comparing the concordance rate of the illness in monozygotic and dyzygotic twins. Underlying the method of twin studies is the supposition that the environment for MZ twins and DZ twins is the same, or at least it does not differ in such a way as to cause greater concordance for MZ twins. Although it is known that the environments shared by MZ twins are more often similar than those shared by DZ twins, these similarities are thought not to be of aetiological relevance to anorexia nervosa.(55) The first sizeable series of twins came from the Maudsley Hospital and St George’s Hospital in London and showed higher concordance rate for MZ than for DZ twins.(56) Since then the findings have been replicated and the analysis of the twin data has suggested that the liability can be broken down into three sources of variability:

a2 Additive genetic effects | 88 per cent |

c2 Common environmental effects, found to be | 0 |

e2 Individual-specific environmental effects.(55) | 12 per cent |

The individual-specific environmental effects are those which contribute to differences between the members of the twin pair. This would happen if only one member of the twin pair had suffered from an adverse effect. It is perhaps surprising that the unique environmental effects contribute to the disorder but not the twins’ common environment.

Bulik has found the concept of heritability and its estimation prone to misinterpretation. There is not just one heritability estimate because this statistic varies across the population sampled and the time of the study. One estimate of heritability of anorexia nervosa gave it as 0.74 in 17-year-old female twins.(55)

It remains uncertain how the genetic vulnerability to anorexia nervosa expresses itself in terms of the pathogenesis of this disorder. One view is that this vulnerability confers instability of the homeostatic mechanisms, which normally ensure the restoration of weight after a period of weight loss. This hypothesis would explain why in western societies, where dieting behaviour is common, those who are genetically vulnerable would be more likely to develop anorexia nervosa.(57) It has also been found that MZ twins have a higher correlation for the trait of ‘body dissatisfaction’ than DZ twins.(55)

(d) Neurotransmitters

Since the early 1970s, the hypothalamic model of anorexia nervosa has been transformed from a consideration of anatomical ‘centres’ to ‘systems’ involving neurotransmitters. Much evidence has been presented to show that a wide range of neurotransmitters modulate feeding behaviour, and it was only a small conceptual step to suggest that some were involved in the pathophysiology of eating disorders. At first the neurotransmitters considered were mainly the monoamine systems-noradrenaline (norepinephrine), dopamine, and serotonin. In addition, opioids, the peptide cholecystokinin, and the hormones corticotrophin-releasing factor and vasopressin have also been thought to play a part in the pathogenesis of eating disorders. During recent years the main interest has been focused on the role of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) in the control of natural appetite, especially those aspects concerning the phenomenon of satiety, mediated through a range of processes called the ‘satiety cascade’.(58) There is now strong evidence that pharmacological activation of serotonin leads to an inhibition of food consumption. It was also postulated that a defect in serotonin metabolism confers a vulnerability to the development of an eating disorder.(59)

A boost to the concept of altered serotonin activity in anorexia nervosa has come from research showing that these patients while still underweight had significant reductions in cerebrospinal fluid 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA). The levels became normal when the patients were retested 2 months after they reached their target weight.(60) In order to test whether these findings were secondary to malnutrition, the researchers resorted to the ingenious step of studying patients after ‘recovery’ when they had reached normal weight. They found elevated levels of cerebrospinal fluid 5-HIAA, possibly indicating increased serotonin activity contributing to the abnormal eating behaviour which often persists in patients who have otherwise recovered.(61) The arguments against this simple model of enhanced serotonin activity as a vulnerability trait in anorexia nervosa should be briefly presented. Serotonin function was again assessed in long-term weight-restored anorectics.(62) The investigators used a dynamic neuroendocrine challenge with d-fenfluramine as a specific probe of serotonin function, which mediates the release of prolactin. If there were any persistent abnormality in serotonin function, the response to this challenge test should differ from that in normal controls. In fact, the rise in prolactin levels was very similar in former patients and normal controls. Accordingly, this study failed to support the notion of increased central serotonin function as a vulnerability trait in anorexia nervosa.(62)

Clinical features: classical anorexia nervosa (postpubertal)

The illness usually occurs in girls within a few years of the menarche so that the most common age of onset is between 14 and 18. Sometimes the onset is later in a woman who has married and had children.

By the time the patient has been referred for psychiatric treatment she is likely to have reduced her food intake and lost weight over the course of several months, and her menstrual periods will have ceased. A regular feature of the illness is its concealment and the avoidance of treatment. Even after having lost 5 to 10 kg in weight and missed several periods, the patient’s opening remark is often ‘there is nothing wrong with me, my parents are unduly worried’. It is only when the clinician asks direct questions that she will admit to insomnia, irritability, sensitivity to cold, and a withdrawal from contacts with her friends, including her boyfriend if she has one.

Because of this denial, it is important to enquire from a close relative, as well as the patient, about the most relevant behavioural changes.

History

History of food intake. A food intake history is obtained by asking the patient to recall what she has eaten on the previous day, commencing with breakfast, which is often missed. An avoidance of carbohydrate and fat-containing foods is the rule. What remains is an often stereotyped selection of vegetables and fruit. ‘Diet’ drinks and unsweetened fruit juice are preferred, although some patients are partial to black coffee. It is the mother who will indicate that her daughter finds ways of avoiding meals, preferring to prepare her own food and withdrawing into her bedroom to eat it.

Weight history. The patient is usually willing to provide an accurate weight history. She may try to conceal her optimum weight before her decision to ‘diet’, but she is likely to be objective about her current weight, if only to express pride in the degree of ‘self-control’ she has exerted. The clinician then has an opportunity to enquire into her ‘desired’ weight by simply asking what weight she would be willing to return to. Her answer will betray a determination to maintain a suboptimal weight.

History of exercising. A history of exercising should be taken. Again, the patient is likely to conceal the fact that she walks long distances to school or to work rather than use public transport. She may also cycle vigorously or attend aerobic classes. A parent may report that his or her daughter is running on the spot or performing press-ups in the privacy of her bedroom, judging from the noise that can be heard. The amount of exercising may be grossly excessive, with the patient indulging in brisk walks or jogging even in the presence of painful knees or ankles due to soft tissue injuries.

Additional harmful behaviours, which should be enquired into include self-induced vomiting, purgative abuse, and self-injury. Vomiting and purgative abuse are similar to the behaviours that occur in bulimia nervosa (see Chapter 4.10.2). In anorexia

nervosa they may occur without the prelude of overeating and the patient’s motive is simply to accelerate weight loss. The laxative abuse is often at the end of the day. The favourite laxatives in the United Kingdom are Senokot and Dulcolax, and the patient is likely to take them in increasing quantities to achieve the wanted effect as tolerance develops. Self-injury should also be enquired into, and the skin of the wrists and forearms inspected for scratches or cuts with sharp instruments.

nervosa they may occur without the prelude of overeating and the patient’s motive is simply to accelerate weight loss. The laxative abuse is often at the end of the day. The favourite laxatives in the United Kingdom are Senokot and Dulcolax, and the patient is likely to take them in increasing quantities to achieve the wanted effect as tolerance develops. Self-injury should also be enquired into, and the skin of the wrists and forearms inspected for scratches or cuts with sharp instruments.

Menstrual history. The patient may not volunteer that her periods ceased soon after commencing the weight-reducing diet. On the other hand she may admit that she is relieved that her periods have stopped as she found them to be a nuisance or unpleasant.

(a) The patient’s mental state

(i) Specific psychopathology

Several near-synonyms have been used to describe the specific attitude detectable in the patient who systematically avoids fatness: a ‘disturbance of body image’,(5) a ‘weight phobia’,(29) or a ‘fear of fatness’.(6) Magersucht, or seeking after thinness, was a term applied in the older German literature. The patient will express a sensitivity about certain parts of her body, especially her stomach, thighs, and hips. Not only is she likely to assert that fatness makes her unattractive, but she may add that it is a shameful condition betraying greed and social failure. These distorted attitudes generally amount to overvalued ideas rather than delusions. Occasionally, however, a patient may be frankly deluded, such as one young woman who believed that her low weight was due to thin bones and that fatness was still evident on the surface of her body.

Studies have demonstrated that wasted patients, when asked to estimate their body size, see themselves as wider and fatter than they actually are.(63) Since these early observations, numerous perceptual studies have been undertaken and the conclusion drawn that anorexic patients overestimate their body width more often than normal controls. These distorted attitudes are often associated with a negative affect, so that the disturbance might be viewed as one of ‘body disparagement’.(64)

The patient’s dread of fatness is so common that it is pathognomonic of anorexia nervosa. There are, however, exceptions. Sometimes a patient may simply deny these faulty attitudes. Another exception is the occurrence of anorexia nervosa in eastern countries where thinness is not generally admired (e.g. Hong Kong and India). The imposition of fear of fatness as a diagnostic criterion on patients from a different culture, where slimness is not valued, amounts to a failure to understand the illness in the context of its culture.(65) An appropriate solution, proposed by Blake Woodside(66) is to accept diagnostic criteria where the psychopathology includes culture-specific symptoms which will differ for western, Chinese, and Indian ethnic groups.

(ii) Denial

Denial in anorexia nervosa is sometimes included within diagnostic criteria of the disorder, for example DSM-IV. Vandereycken(67) has written a scholarly treatize on the subject. He has pointed out that the term ‘denial’ is used with apparently simplicity in clinical practice, but this stands in contrast to its intriguing complexity. It is a multi-layered concept, which is difficult to measure. Denial is not a static condition but fluctuates over time. A crucial element in its assessment is the inherent conflict of perception between the patient and the clinician. The patient carries out distortions by omissions, concealments, or misrepresentations. She often denies hunger and fatigue and appears not to accept that she is thin. She shows a lack of concern for the physical and psychosocial sequelae of being underweight and may even deny the danger of her condition.

Vandereycken has proposed two categories of denial:

1 Unintentional denial (e.g. the patient’s way to improve her self-esteem and preserve her sense of identity).

2 A deliberate denial including the pretence of being healthy and avoiding the treatment others want her to accept. Strong denial is often accompanied by the avoidance of treatment, but the refusal of help is not entirely due to the patient’s lack of recognition of her problems.

(iii) Depression

Depression of varying severity, including a major depressive disorder, is common. The patients express guilt after eating, adding that they do not deserve food. A high rate of depression (42 per cent) was found at presentation in one study(21) and the lifetime history of depression in follow-up studies may be as high as 68 per cent.

(iv) Obsessive-compulsive features

The patients frequently eat in a ritualistic way, for example restricting their food intake to a narrow range of foods which experience tells them are ‘safe’ because they will not lead to weight gain. There is often a compulsive need to count the daily caloric intake. One patient rejected prescribed vitamin tablets in case they contained ‘calories’. The frequency of obsessive-compulsive disorder in anorexia nervosa was found to be 22 per cent in a clinical series.(21) In studies using structured clinical interviews the frequency ranged from 25 to 70 per cent.

(v) Neuropsychological deficits

These deficits are seldom detected clinically, and an emaciated patient may pursue studies and obtain surprisingly good examination marks. On the other hand, neuropsychological testing has revealed deficits in attention, and impairment of memory and visuospatial function.(59)

(b) The endocrine disorder

(i) The impairment of hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function

Amenorrhoea is an early symptom of anorexia nervosa and in a minority of patients may even precede the onset of weight loss. Amenorrhoea is an almost necessary criterion for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa. An exception is when a patient takes a contraceptive pill, which replaces the hormonal deficit and may lead her to say she still has her periods.

Generally, when the patient is undernourished, levels of gonadotrophins and oestrogens in the blood are found to be low or undetectable. Not only do malnourished patients show low blood levels of luteinizing hormone and follicle-stimulating hormone, but the secretion patterns of these pituitary hormones regress to a phase of earlier development. For example, severely wasted patients display an infantile luteinizing hormone secretory pattern with a lack of major fluctuations over the course of 24 h. With some degree of weight gain a pubertal secretory pattern appears, consisting first of a sleep-dependent increase of luteinizing hormone at night, and later displaying more frequent fluctuations.(68)

When a patient is still malnourished the ultrasound pelvic examination will reveal that ovarian volume is much smaller than in normal women.(69) Three stages can be discerned in the appearance of the ovaries as the patient gains weight:

When a patient is still malnourished the ultrasound pelvic examination will reveal that ovarian volume is much smaller than in normal women.(69) Three stages can be discerned in the appearance of the ovaries as the patient gains weight:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree