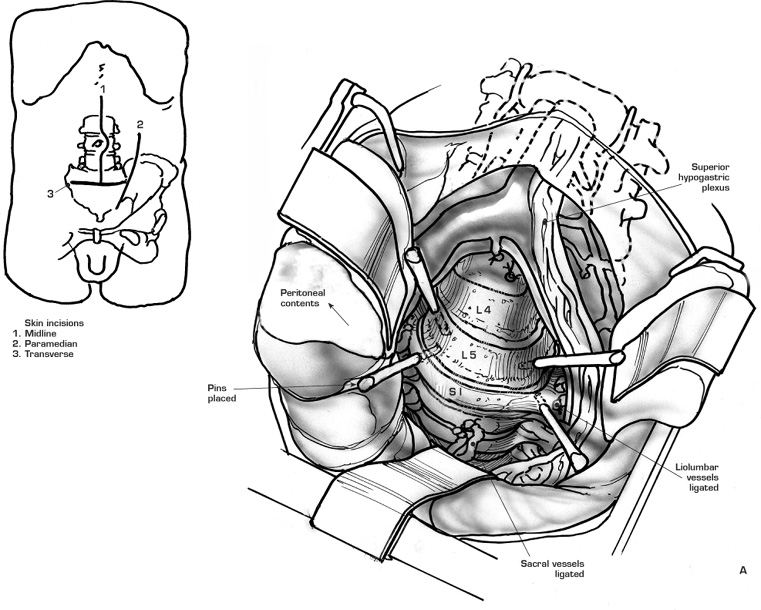

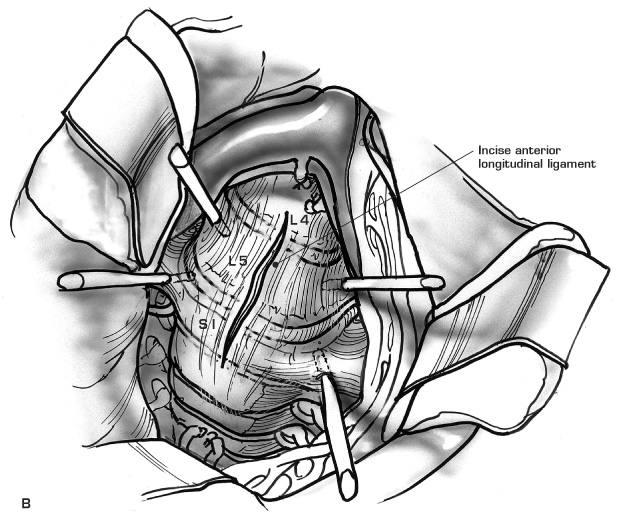

51 Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion To achieve a solid stable interbody fusion. Chronic mechanical low back pain, often with intermittent episodes of more severe low back pain. Physical examination reveals tenderness over the lumbosacral junction, and possibly anterior spinal tenderness on abdominal examination, painful limitation of active lumbosacral range of motion as well as signs suggesting spinal instability. Neurologic examination may reveal no objective deficits. Radiologic studies may demonstrate loss of intervertebral disc height with signs suggestive of lumbar spondylosis. Stress discography, with or without postdiscogram computed tomography (CT), reveals an abnormal nucleogram dye pattern and concordant symptom reproduction. 1. Internal disc disruption 2. Isolated disc resorption 3. Failed spinal surgical syndrome 1. Unrealistic expectations or marked functional overlay 2. Previous retroperitoneal exposure and dissection 3. Retroperitoneal fibrosis and adhesions 4. Previous anterior lumbar interbody fusion 5. Anomalies of the aorta and inferior vena cava as well as its branches 6. Deep venous thrombosis of the iliofemoral veins 7. Markedly obese patients 1. The ability to perform a complete disc excision 2. Large area of bone available for fusion 3. The avoidance of epidural scarring and fibrosis associated with intrusion into the epidural space 4. The avoidance of “postfusion syndrome” associated with a posterior surgery 5. A greater facility to restore lumbar lordosis and appropriate sagittal alignment 1. Decreased ability to deal with spinal canal pathology. 2. The use of internal fixation in the lower lumbar spine, particularly at L5-S1, is limited because of the proximity of major arteries and veins, as well as the anatomic orientation of the lumbosacral disc. 3. The relative osteopenia of the anterior and middle column compared to the posterior column, namely, lamina and pedicles. Appropriate preoperative medical and anesthetic assessment is done, with special attention to the cessation of all medications that may interfere with the clotting process (e.g., aspirin). Preoperative bowel preparation should be considered, including the use a bowel prep enema the night prior to surgery as well as appropriate bathing and body cleansing. All preoperative radiologic studies should be available. The recommended anesthetic technique includes: 1. Perioperative prophylactic antibiotics. 2. Relative hypotension compatible with the patient’s cardiovascular function. 3. Muscle relaxation. 4. A radiolucent operating table that can be hyperextended. 5. A bean bag is routinely used. 6. The use of the atraumatic rectus splitting approach to the lumbosacral junction requires the patient be placed supine on the table and positioned appropriately with the break of the table at the level of the iliac crests. 7. Gel pads of various sizes can be used to support and place the sacrum and pelvis in the appropriate position to aid access to the lumbosacral junction. Compressive calf stockings are required to provide deep vein thrombosis prophylaxis. 8. In those patients where the rectus splitting approach is not recommended or difficult (e.g., from significant obesity), a lateral abdominal approach with muscle splitting dissection is required, and the patient must be positioned in the left lateral decubitus position. A left transverse abdominal incision at the level indicated by the assessment of the radiologic studies noting the relationship of the iliac crest to the lumbosacral junction. A left paramedial vertical incision may be required for a more extensile approach in larger patients or where dissection is difficult. A transverse incision is made through the anterior rectus sheath with a medial caudal extension and a lateral cephalic extension (Fig. 51–1). Medial retraction of the rectus muscle is aided by division of the neurovascular bundle (avoid the division of more than two contiguous neurovascular bundles, which may result in denervation) (Fig. 51–2A). Division of the lateral posterior rectus sheath is made with a lateral vertical incision (to prevent simultaneous incision of the anterior peritoneum) (Fig. 51–2B). Blunt dissection (with swab sticks or fingers) laterally toward the psoas muscle mobilizes the peritoneal sac from the psoas muscle. Continue the dissection, pulling up the peritoneal contents away from the perivertebral area and across to the midline and to the right. The ureter should be carried forward with the posterior peritoneal sheath. Avoid interference and damage to the ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerve. Identify the aortic bifurcation with palpation of the pulse. Palpate the more prominent lumbosacral disc in the bifurcation of the aorta. Mobilize the area of the aortic bifurcation first in the cephalic direction and then to the right and to the left. Use blunt-tipped retractors (e.g., modified Hibbs retractors). Use peanuts or Kitner dissectors held in long vascular clamps to continue the atraumatic blunt dissection of the lumbosacral disc. The blunt dissection should start on the right-hand side of the left iliac vessels and then proceed to sweep from the left to the right across the disc space, with strict avoidance of electrocautery for hemostasis in male patients. The use of appropriate-sized Hemaclips allows control with division of the vertically running median sacral artery and vein (if prominent). Use pressure to control small vessel hemorrhage during the dissection and clearance of the lumbosacral disc. It is expected that the bifurcation will be at the L4-L5 disc. A higher bifurcation makes the approach to the L5-S1 disc easier, whereas a lower bifurcation may result in the inability to have adequate clearance at the bifurcation and a left lateral approach to the disc may then be required. The common iliac vein beneath the aortic bifurcation (running diagonally to the left) is most at risk. There may be short venous structures running from the anterior longitudinal ligament to the common iliac vein that may require ligation and control. The mobilization of the bifurcation of the aorta and the common iliac arteries is less of a problem, except in cases where calcification (as seen on x-ray) may render the arteries rigid and less amenable to dissection and mobilization, and increase the possibility of thrombosis and embolism. If a left lateral approach is used or required, it is essential to identify, isolate, and control the iliolumbar, ascending lumbar, and fifth lumbar veins. These veins, particularly the lumbar and ascending lumbar veins, require double ligation (with a ligature and a stitch ligature) rather than the use of a Hemaclip. These vessels may have a short, wide bore and may have immediate double or triple divisions with one or more deep in the psoas. If uncontrolled, they can cause dangerous and rapid blood loss. The arteries and veins can then be mobilized from the left to the right, exposing adequate access to the left anterolateral aspects of the lumbosacral disc. Safe, adequate retraction of the major blood vessels is an essential part of performing an anterior lumbar fusion at L5-S1. Such retractors include malleable ribbon retractors, modified Deever retractors (with a smooth excavated end), and the Oswestry O’Brien retractors; Steinmann pins are used, which are protected with red Robinson catheters. Figure 51–1 Figure 51–2

Goals of Surgical Treatment

Diagnosis

Indications for Surgery

Contraindications

Advantages

Disadvantages

Procedure

Preoperative

Intraoperative

Surgical Incision Approach and Dissection

Control and Mobilization of the Blood Vessels

Retraction

Skin incisions as related to the spine level, iliac crest, and pubic symphysis.

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree