Antidepressant drugs

Antidepressant drugs, as their name suggests, were developed for the treatment of depressive disorders. They are most effective in the treatment of moderate and severe depressive episodes. It is uncertain whether they are helpful in mild depressive episodes and any efficacy they have in this condition is probably outweighed by the risk of adverse effects, as these milder illnesses often improve spontaneously or with simple non-pharmacological interventions (see p. 54). Antidepressants are also effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Tricyclic antidepressants are used in low doses for the treatment of some chronic pain syndromes.

How do antidepressants work?

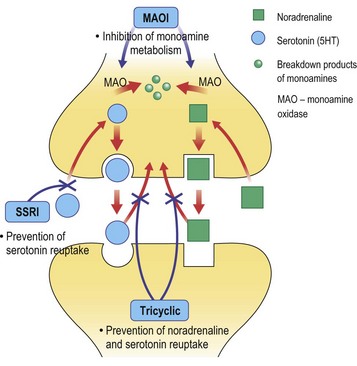

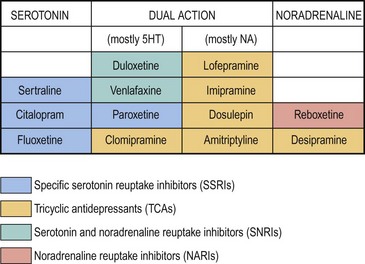

All the antidepressants developed since have an effect on either noradrenaline or serotonin, as illustrated in Figure 1. The relative effects of the monoamine reuptake inhibitors are shown in Figure 2. Some antidepressant drugs affect monoamines in novel ways, such as mirtazapine, which antagonises the presynaptic adrenergic autoreceptors that inhibit serotonin and noradrenaline release.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree