12

Antiepileptic Drug Adverse Effects: What to Watch Out For

Introduction

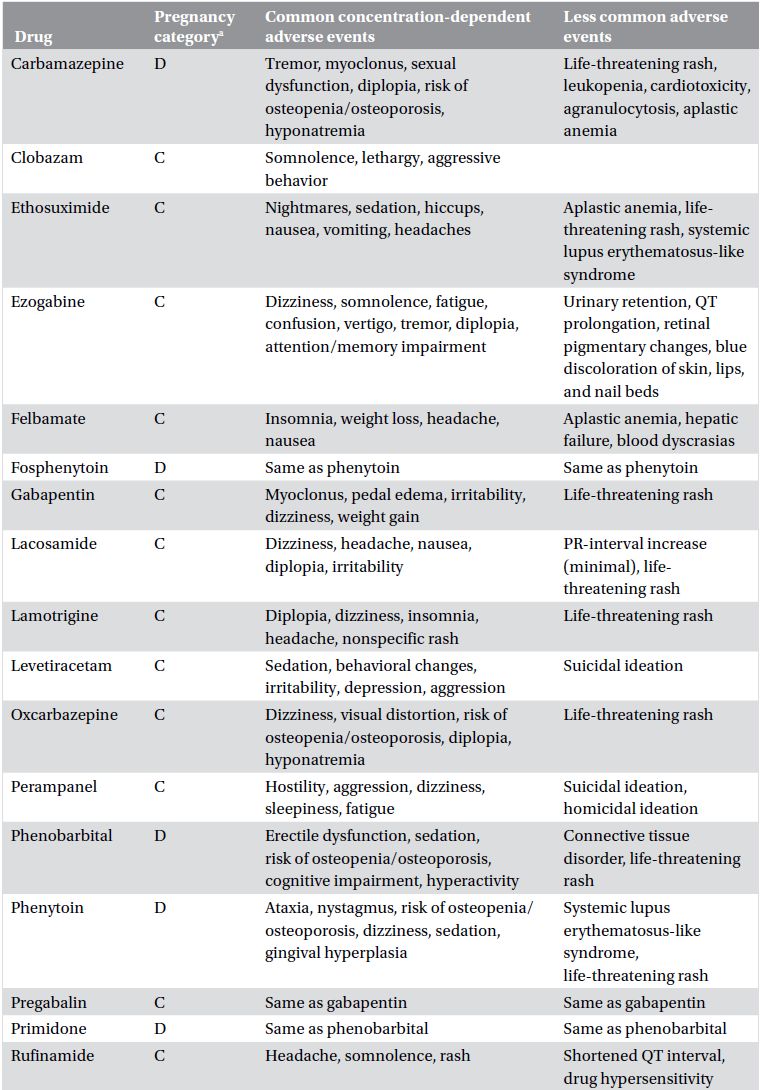

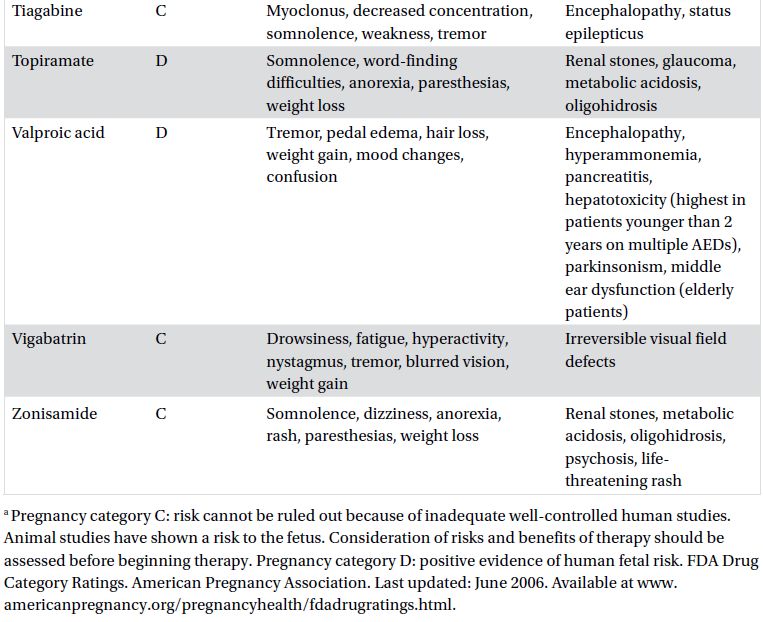

Adverse effects can occur with any drug but are particularly common with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). They occur in as many as 88% of surveyed patients. Most pharmacological adverse reactions are typically dose dependent and often occur during introduction of the medication. Pharmacological adverse reactions sometimes correlate with higher serum drug levels and resolve when the dose is reduced. Idiosyncratic adverse reactions to AEDs are rare, not related to the agent’s pharmacology, do not show an obvious relationship with the dose, and may not resolve with removal of the drug. These idiosyncratic events cannot be prevented by monitoring serum levels or other blood tests. This chapter outlines the pharmacological and idiosyncratic adverse effects of AEDs (Table 12.1) that one must be familiar with to optimally manage these medications.

Common adverse effects

Neurological

The most common central nervous system (CNS) pharmacological adverse effects are sedation and fatigue. However, a few AEDs, particularly felbamate and lamotrigine, are associated with insomnia and disturbed sleep. Other common CNS side effects are dizziness, visual distortion, eye movement abnormalities, tremor, ataxia, cognitive impairment, and headaches. These effects can be bothersome and lead to poor medication compliance, discontinuation, or failure to reach effective dosing. Slow dose escalation when introducing an agent or lowering the dose and reescalating more slowly over time may reduce these complaints.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Dizziness is particularly common in agents with a primary mechanism of sodium channel blockade. Often, this is a peak-dose effect, occurring an hour or two after the drug is taken. Visual distortions such as diplopia, trailing vision, and blurred vision are common complaints with carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and lamotrigine that also correlate with peak levels.

Common ocular side effects include nystagmus and saccadic intrusions during smooth pursuit. The saccadic intrusions are rarely perceived by the patients and can be used as a simple measure on examination to screen for adherence. On the other hand, nystagmus may affect vision and require a dose reduction. Similarly, tremor and gait ataxia may interfere with activities of daily living and often lead to a decrease in dose.

Table 12.1. Pharmacological and idiosyncratic adverse effects of AEDs.

Cognitive dysfunction can occur with any AED but is commonly associated with barbiturates, topiramate, and zonisamide. Polypharmacy can also increase the risk of cognitive dysfunction as well. Complaints often include difficulties with verbal expression or word finding, mental slowing, and poor concentration. These complaints are often dose related and can be more problematic in those over 60 years of age. AED overdose can lead to encephalopathy. Rarely, there may be specific AED-mediated mechanisms contributing to a stuporous state, such as valproate-induced hyperammonemia or tiagabine-related nonconvulsive status epilepticus.

TIPS AND TRICKS

TIPS AND TRICKSPsychiatric

Adverse effects of AEDs on mood and behavior are major determinants of quality of life. These effects may range from mild irritability to psychosis, but the most common issue is depression. Levetiracetam is an agent currently in wide use that is more likely to have adverse effects on mood than other AEDs. On the other hand, euphoria has been seen with lacosamide and pregabalin. Homicidal ideation has been reported with higher doses of perampanel in clinical trials.

TIPS AND TRICKS

TIPS AND TRICKSStarting at high doses and escalating too quickly increases the risk of mood and behavioral adverse effects with several AEDs but is more of a concern with topiramate. Caution should be used in those with preexisting psychiatric disorders. Antidepressants may be helpful even when depressive adverse effects occur in those without preexisting mood disorders. Psychiatric disorders in epilepsy and their associations with AED use are discussed further in Chapter 37.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree