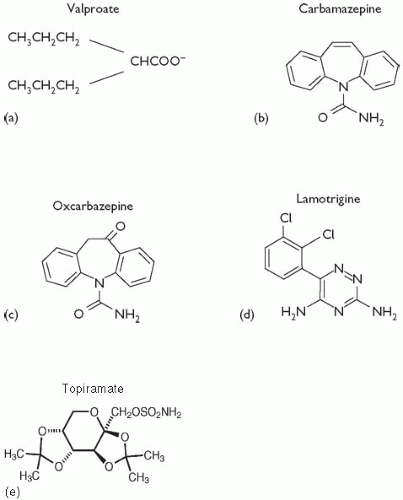

In general, valproate can be combined safely with other psychotropic medications and antiepileptic drugs. However, given that valproate is highly protein-bound and can inhibit hepatic enzymes, some drug– drug interactions have been identified.

(3) Aspirin, which is highly protein-bound, elevates the free fraction of valproate, resulting in increased effects of valproate on the CNS. Valproate can displace

diazepam,

phenytoin,

carbamazepine, and

warfarin from proteinbinding sites, resulting in increased activity of these drugs. Co-administration of valproate with

lamotrigine significantly increases the half-life of the latter and can increase the risk of lamotrigine-induced rashes. When administered with

carbamazepine, three potential interactions may occur: (1) valproate can increase the concentration of carbamazepine’s metabolite, carbamazepine-10,11-epoxide, by inhibiting its further metabolism; (2) carbamazepine may lower the valproate level; and (3) valproate may increase the carbamazepine level.

(24) Therefore, close monitoring of serum

concentrations of both drugs is important when they are combined.

Amitriptyline and

fluoxetine may increase serum valproate concentrations, possibly by inhibition of valproate metabolism.