Screening requires asking about both physical and psychological symptoms of anxiety.

The somatic presentation of anxiety disorders, where physical symptoms predominate, is common in the primary care setting.

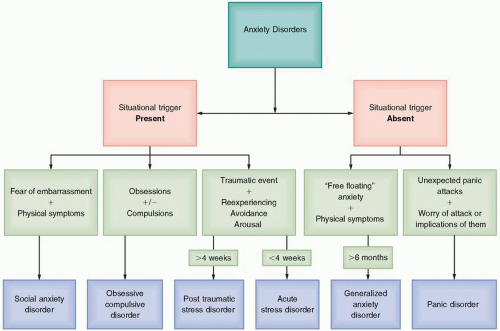

Specific anxiety disorders are defined and categorized by the presence or absence of specific situational triggers.

More than 70% of patients diagnosed with an anxiety disorder in the primary care setting also have another comorbid Axis I condition, most commonly depression and another anxiety disorder. The AMPS screening tool is a quick and effective way to screen for anxiety, mood, psychotic, and substance misuse disorders.

Initial management of anxiety disorders includes establishing a trusting relationship while addressing psychosocial stressors in an empathic way.

General medical conditions can trigger as well as masquerade an anxiety disorder; both need to be treated.

Cognitive behavioral therapy or medication management with serotonin reuptake inhibitors are both first-line treatment options regardless of the specific anxiety disorder. In general, when treating an anxiety disorder, it is best to start with half the normal antidepressant starting dose because this may decrease irritability and anxiety during the first few weeks of treatment.

Success with medications relies more on providing good patient information and follow-up than prescribing a specific drug.

excessive and paralyzes one from taking a needed action despite the possible repercussions (or missed opportunities). In order to ensure an accurate diagnosis and effective treatment plan, it is important to document the disability, screen for an anxiety disorder, consider the differential diagnosis, and identify the specific anxiety disorder.

Social impairment: withdrawal from family, friends, and hobbies

Occupational impairment: job avoidance, inefficiency, lack of promotion, or even disciplinary action

Impairment with activities of daily living: inability to shop for groceries, take the bus, or drive a car

Table 4.1 GAD-7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

within 10 minutes and rarely last longer than an hour. During a panic attack, psychological symptoms often include fears of losing control, dying, or “going crazy.” Physical symptoms reflecting autonomic activation are equally intense and include a racing heart rate, sweating, shaking, shortness of breath, nausea, dizziness, and chest discomfort.

Although panic attacks can be terrifying and temporarily disabling, it is the anticipatory anxiety of when the next attack will come and the worry about its implications that perpetuates the disability. Patients may undergo extensive testing to find the etiology of symptoms, such as chest discomfort or gastrointestinal symptoms, before a diagnosis of PD is made. PD is twice as common in women as in men and onset peaks in late adolescence and the mid-30s. Although the initial panic attack is by definition not caused by an obvious trigger, the majority of patients report some antecedent adverse life event in the year prior to onset of illness.

intrusive ideas, thoughts, impulses, or images. Common themes include contamination, repeated doubts, need for order, horrific thoughts, and sexual imagery. Compulsions are ritualistic behaviors or mental acts carried out in response to an obsession. Examples include repeated handwashing, checking of locks, and counting.

disorder is the close temporal relationship of the onset of anxiety symptoms to a stressful event, usually within days, and resolution within 6 months of the termination of the stressor. Although symptoms may initially be quite intense, they are generally short-lived and diminish with the passage of time. There is symptom overlap with other disorders, but the duration and threshold specifiers distinguish adjustment disorder from other anxiety disorders. For example, GAD requires symptoms to be present for at least 6 months and PTSD and ASD require the stressor to be extreme in nature. Unlike the other anxiety disorders, there is an expectation of good outcome with adjustment disorder once the offending stressor is removed. If the stressor persists, anxiety symptoms will be present in a more attenuated form. Treatment is supportive to help the patient resolve or manage the stressor. Pharmacotherapy with antidepressants and benzodiazepines is sometimes utilized, but there is little evidence to support this practice.

Table 4.2 Medical Conditions with Anxiety-Like Symptoms | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

substances in the past month. If abuse or dependence is detected, the longitudinal history is helpful in determining if current symptoms represent a substance-induced state or comorbid substance abuse and anxiety disorder. History suggesting two separate disorders would include (1) onset of symptoms prior to first use of the substance and (2) continued symptoms despite sustained abstinence for at least 1 month. Management of comorbid substance abuse and anxiety disorders include treatment for the anxiety disorder in addition to the substance abuse treatment.

Table 4.3 Medications and Substances That Cause Anxiety-Like Symptoms | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree