Anxiety Disorders

9.1 Overview

9.1 Overview

Anxiety represents a core phenomenon around which considerable psychiatric theory has been organized. Thus, the term “anxiety” has played a central role in psychodynamic theory, as well as in neuroscience-focused research and various schools of thought heavily influenced by cognitive-behavioral principles. Anxiety disorders are associated with significant morbidity and often are chronic and resistant to treatment. Anxiety disorders can be viewed as a family of related but distinct mental disorders, which include (1) panic disorder, (2) agoraphobia, (3) specific phobia, (4) social anxiety disorder or phobia, and (5) generalized anxiety disorder. Each of these disorders is discussed in detail in the sections that follow.

A fascinating aspect of anxiety disorders is the exquisite interplay of genetic and experiential factors. Little doubt exists that abnormal genes predispose to pathological anxiety states; however, evidence clearly indicates that traumatic life events and stress are also etiologically important. Thus, the study of anxiety disorders presents a unique opportunity to understand the relation between nature and nurture in the etiology of mental disorders.

NORMAL ANXIETY

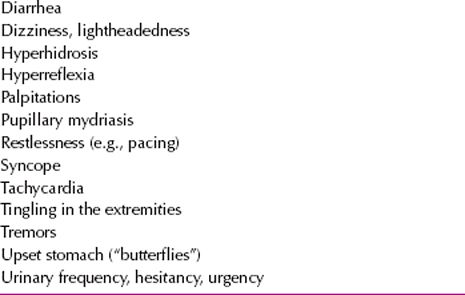

Everyone experiences anxiety. It is characterized most commonly as a diffuse, unpleasant, vague sense of apprehension, often accompanied by autonomic symptoms such as headache, perspiration, palpitations, tightness in the chest, mild stomach discomfort, and restlessness, indicated by an inability to sit or stand still for long. The particular constellation of symptoms present during anxiety tends to vary among persons (Table 9.1-1).

Table 9.1-1

Table 9.1-1

Peripheral Manifestations of Anxiety

Fear versus Anxiety

Anxiety is an alerting signal; it warns of impending danger and enables a person to take measures to deal with a threat. Fear is a similar alerting signal, but it should be differentiated from anxiety. Fear is a response to a known, external, definite, or nonconflictual threat; anxiety is a response to a threat that is unknown, internal, vague, or conflictual.

This distinction between fear and anxiety arose accidentally. When Freud’s early translator mistranslated angst, the German word for “fear,” as anxiety, Freud himself generally ignored the distinction that associates anxiety with a repressed, unconscious object and fear with a known, external object. The distinction may be difficult to make because fear can also be caused by an unconscious, repressed, internal object displaced to another object in the external world. For example, a boy may fear barking dogs because he actually fears his father and unconsciously associates his father with barking dogs.

Nevertheless, according to postfreudian psychoanalytic formulations, the separation of fear and anxiety is psychologically justifiable. The emotion caused by a rapidly approaching car as a person crosses the street differs from the vague discomfort a person may experience when meeting new persons in a strange setting. The main psychological difference between the two emotional responses is the suddenness of fear and the insidiousness of anxiety.

In 1896, Charles Darwin gave the following psychophysiological description of acute fear merging into terror:

Fear is often preceded by astonishment, and is so far akin to it, that both lead to the senses of sight and learning being instantly aroused. In both cases the eyes and mouth are widely opened, and the eyebrows raised. The frightened man at first stands like a statue motionless and breathless, or crouches down as if instinctively to escape observation. The heart beats quickly and violently, so that it palpitates or knocks against the ribs; but it is very doubtful whether it then works more efficiently than usual, so as to send a greater supply of blood to all parts of the body; for the skin instantly becomes pale, as during incipient faintness. This paleness of the surface, however, is probably in large part, or exclusively, due to the vasomotor center being affected in such a manner as to cause the contraction of the small arteries of the skin. That the skin is much affected under the sense of great fear, we see in the marvelous and inexplicable manner in which perspiration immediately exudes from it. This exudation is all the more remarkable, as the surface is then cold, and hence the term a cold sweat; whereas, the sudorific glands are properly excited into action when the surface is heated. The hairs also on the skin stand erect; and the superficial muscles shiver. In connection with the disturbed action of the heart, the breathing is hurried. The salivary glands act imperfectly; the mouth becomes dry, and is often opened and shut. I have also noticed that under slight fear there is a strong tendency to yawn. One of the best-marked symptoms is the trembling of all the muscles of the body; and this is often first seen in the lips. From this cause, and from the dryness of the mouth, the voice becomes husky or indistinct, or may altogether fail….

As fear increases into an agony of terror, we behold, as under all violent emotions, diversified results. The heart beats wildly or may fail to act and faintness ensues; there is a deathlike pallor; the breathing is labored; the wings of the nostrils are widely dilated; there is a gasping and convulsive motion on the lips, a tremor on the hollow cheek, a gulping and catching of the throat; the uncovered and protruding eyeballs are fixed on the object of terror; or they may roll restlessly from side to side. The pupils are said to be enormously dilated. All the muscles of the body may become rigid, or may be thrown into convulsive movements. The hands are alternately clenched and opened, often with a twitching movement. The arms may be protruded, as if to avert some dreadful danger, or may be thrown wildly over the head….In other cases there is a sudden and uncontrollable tendency to headlong flight; and so strong is this, that the boldest soldiers may be seized with a sudden panic.

Is Anxiety Adaptive?

Anxiety and fear both are alerting signals and act as a warning of an internal and external threat. Anxiety can be conceptualized as a normal and adaptive response that has lifesaving qualities and warns of threats of bodily damage, pain, helplessness, possible punishment, or the frustration of social or bodily needs; of separation from loved ones; of a menace to one’s success or status; and ultimately of threats to unity or wholeness. It prompts a person to take the necessary steps to prevent the threat or to lessen its consequences. This preparation is accompanied by increased somatic and autonomic activity controlled by the interaction of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems. Examples of a person warding off threats in daily life include getting down to the hard work of preparing for an examination, dodging a ball thrown at the head, sneaking into the dormitory after curfew to prevent punishment, and running to catch the last commuter train. Thus, anxiety prevents damage by alerting the person to carry out certain acts that forestall the danger.

Stress and Anxiety

Whether an event is perceived as stressful depends on the nature of the event and on the person’s resources, psychological defenses, and coping mechanisms. All involve the ego, a collective abstraction for the process by which a person perceives, thinks, and acts on external events or internal drives. A person whose ego is functioning properly is in adaptive balance with both external and internal worlds; if the ego is not functioning properly and the resulting imbalance continues sufficiently long, the person experiences chronic anxiety.

Whether the imbalance is external, between the pressures of the outside world and the person’s ego, or internal, between the person’s impulses (e.g., aggressive, sexual, and dependent impulses) and conscience, the imbalance produces a conflict. Whereas externally caused conflicts are usually interpersonal, those that are internally caused are intrapsychic or intrapersonal. A combination of the two is possible, as in the case of employees whose excessively demanding and critical boss provokes impulses that they must control for fear of losing their jobs. Interpersonal and intrapsychic conflicts, in fact, are usually intertwined. Because human beings are social, their main conflicts are usually with other persons.

Symptoms of Anxiety

The experience of anxiety has two components: the awareness of the physiological sensations (e.g., palpitations and sweating) and the awareness of being nervous or frightened. A feeling of shame may increase anxiety—“Others will recognize that I am frightened.” Many persons are astonished to find out that others are not aware of their anxiety or, if they are, do not appreciate its intensity.

In addition to motor and visceral effects, anxiety affects thinking, perception, and learning. It tends to produce confusion and distortions of perception, not only of time and space but also of persons and the meanings of events. These distortions can interfere with learning by lowering concentration, reducing recall, and impairing the ability to relate one item to another—that is, to make associations.

An important aspect of emotions is their effect on the selectivity of attention. Anxious persons likely select certain things in their environment and overlook others in their effort to prove that they are justified in considering the situation frightening. If they falsely justify their fear, they augment their anxieties by the selective response and set up a vicious circle of anxiety, distorted perception, and increased anxiety. If, alternatively, they falsely reassure themselves by selective thinking, appropriate anxiety may be reduced, and they may fail to take necessary precautions.

PATHOLOGICAL ANXIETY

Epidemiology

The anxiety disorders make up one of the most common groups of psychiatric disorders. The National Comorbidity Study reported that one of four persons met the diagnostic criteria for at least one anxiety disorder and that there is a 12-month prevalence rate of 17.7 percent. Women (30.5 percent lifetime prevalence) are more likely to have an anxiety disorder than are men (19.2 percent lifetime prevalence). The prevalence of anxiety disorders decreases with higher socioeconomic status.

Contributions of Psychological Sciences

Three major schools of psychological theory—psychoanalytic, behavioral, and existential—have contributed theories about the causes of anxiety. Each theory has both conceptual and practical usefulness in treating anxiety disorders.

Psychoanalytic Theories. Although Freud originally believed that anxiety stemmed from a physiological buildup of libido, he ultimately redefined anxiety as a signal of the presence of danger in the unconscious. Anxiety was viewed as the result of psychic conflict between unconscious sexual or aggressive wishes and corresponding threats from the superego or external reality. In response to this signal, the ego mobilized defense mechanisms to prevent unacceptable thoughts and feelings from emerging into conscious awareness. In his classic paper “Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety,” Freud states that “it was anxiety which produced repression and not, as I formerly believed, repression which produced anxiety.” Today, many neurobiologists continue to substantiate many of Freud’s original ideas and theories. One example is the role of the amygdala, which subserves the fear response without any reference to conscious memory and substantiates Freud’s concept of an unconscious memory system for anxiety responses. One of the unfortunate consequences of regarding the symptom of anxiety as a disorder rather than a signal is that the underlying sources of the anxiety may be ignored. From a psychodynamic perspective, the goal of therapy is not necessary to eliminate all anxiety but to increase anxiety tolerance—that is, the capacity to experience anxiety—and use it as a signal to investigate the underlying conflict that has created it. Anxiety appears in response to various situations during the life cycle, and although psychopharmacological agents may ameliorate symptoms, they may do nothing to address the life situation or its internal correlates that have induced the state of anxiety. In the following case, a disturbing fantasy precipitated an anxiety attack.

A married man 32 years of age was referred for therapy for severe and incapacitating anxiety, which was clinically manifested as repeated outbreaks of acute attacks of panic. Initially, he had absolutely no idea what had precipitated his attacks, nor were they associated with any conscious mental content. In the early weeks of treatment, he spent most of his time trying to impress the doctor with how hard he had worked and how effectively he had functioned before he was taken ill. At the same time, he described how fearful he was that he would fail at a new business venture he had embarked on. One day, with obvious acute anxiety that practically prevented him from talking, he revealed a fantasy that had suddenly popped into his mind a day or two before and had led to the outbreak of a severe anxiety attack. He had had the image of a large spike being driven through his penis. He also recalled that, as a child of 7, he was fascinated by his mother’s clothing and that, on occasion, when she was out of the house, he dressed himself up in them. As an adult, he was fascinated by female lingerie and would sometimes find himself impelled by a desire to wear women’s clothing. He had never yielded to the impulse, but on those occasions when the idea entered his consciousness, he became overwhelmed by acute anxiety and panic.

To understand fully a particular patient’s anxiety from a psychodynamic view, it is often useful to relate the anxiety to developmental issues. At the earliest level, disintegration anxiety may be present. This anxiety derives from the fear that the self will fragment because others are not responding with needed affirmation and validation. Persecutory anxiety can be connected with the perception that the self is being invaded and annihilated by an outside malevolent force. Another source of anxiety involves a child who fears losing the love or approval of a parent or loved object. Freud’s theory of castration anxiety is linked to the oedipal phase of development in boys, in which a powerful parental figure, usually the father, may damage the little boy’s genitals or otherwise cause bodily harm. At the most mature level, superego anxiety is related to guilt feelings about not living up to internalized standards of moral behavior derived from the parents. Often, a psychodynamic interview can elucidate the principal level of anxiety with which a patient is dealing. Some anxiety is obviously related to multiple conflicts at various developmental levels.

Behavioral Theories. The behavioral or learning theories of anxiety postulate that anxiety is a conditioned response to a specific environmental stimulus. In a model of classic conditioning, a girl raised by an abusive father, for example, may become anxious as soon as she sees the abusive father. Through generalization, she may come to distrust all men. In the social learning model, a child may develop an anxiety response by imitating the anxiety in the environment, such as in anxious parents.

Existential Theories. Existential theories of anxiety provide models for generalized anxiety, in which no specifically identifiable stimulus exists for a chronically anxious feeling. The central concept of existential theory is that persons experience feelings of living in a purposeless universe. Anxiety is their response to the perceived void in existence and meaning. Such existential concerns may have increased since the development of nuclear weapons and bioterrorism.

Contributions of Biological Sciences

Autonomic Nervous System. Stimulation of the autonomic nervous system causes certain symptoms—cardiovascular (e.g., tachycardia), muscular (e.g., headache), gastrointestinal (e.g., diarrhea), and respiratory (e.g., tachypnea). The autonomic nervous systems of some patients with anxiety disorder, especially those with panic disorder, exhibit increased sympathetic tone, adapt slowly to repeated stimuli, and respond excessively to moderate stimuli.

Neurotransmitters. The three major neurotransmitters associated with anxiety on the bases of animal studies and responses to drug treatment are norepinephrine (NE), serotonin, and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA). Much of the basic neuroscience information about anxiety comes from animal experiments involving behavioral paradigms and psychoactive agents. One such experiment to study anxiety was the conflict test, in which the animal is simultaneously presented with stimuli that are positive (e.g., food) and negative (e.g., electric shock). Anxiolytic drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines) tend to facilitate the adaptation of the animal to this situation, but other drugs (e.g., amphetamines) further disrupt the animal’s behavioral responses.

NOREPINEPHRINE. Chronic symptoms experienced by patients with anxiety disorder, such as panic attacks, insomnia, startle, and autonomic hyperarousal, are characteristic of increased noradrenergic function. The general theory about the role of norepinephrine in anxiety disorders is that affected patients may have a poorly regulated noradrenergic system with occasional bursts of activity. The cell bodies of the noradrenergic system are primarily localized to the locus ceruleus in the rostral pons, and they project their axons to the cerebral cortex, the limbic system, the brainstem, and the spinal cord. Experiments in primates have demonstrated that stimulation of the locus ceruleus produces a fear response in the animals and that ablation of the same area inhibits or completely blocks the ability of the animals to form a fear response.

Human studies have found that in patients with panic disorder, β-adrenergic receptor agonists (e.g., isoproterenol [Isuprel]) and α2-adrenergic receptor antagonists (e.g., yohimbine [Yocon]) can provoke frequent and severe panic attacks. Conversely, clonidine (Catapres), an α2-receptor agonist, reduces anxiety symptoms in some experimental and therapeutic situations. A less consistent finding is that patients with anxiety disorders, particularly panic disorder, have elevated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) or urinary levels of the noradrenergic metabolite 3-methoxy-4-hydroxyphenylglycol (MHPG).HYPOTHALAMIC–PITUITARY–ADRENAL AXIS. Consistent evidence indicates that many forms of psychological stress increase the synthesis and release of cortisol. Cortisol serves to mobilize and to replenish energy stores and contributes to increased arousal, vigilance, focused attention, and memory formation; inhibition of the growth and reproductive system; and containment of the immune response. Excessive and sustained cortisol secretion can have serious adverse effects, including hypertension, osteoporosis, immunosuppression, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, dyscoagulation, and, ultimately, atherosclerosis and cardiovascular disease. Alterations in hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis function have been demonstrated in PTSD. In patients with panic disorder, blunted adrenocorticoid hormone (ACTH) responses to corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) have been reported in some studies and not in others.

CORTICOTROPIN-RELEASING HORMONE (CRH). One of the most important mediators of the stress response, CRH coordinates the adaptive behavioral and physiological changes that occur during stress. Hypothalamic levels of CRH are increased by stress, resulting in activation of the HPA axis and increased release of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA). CRH also inhibits a variety of neurovegetative functions, such as food intake, sexual activity, and endocrine programs for growth and reproduction.

SEROTONIN. The identification of many serotonin receptor types has stimulated the search for the role of serotonin in the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders. Different types of acute stress result in increased 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT) turnover in the prefrontal cortex, nucleus accumbens, amygdala, and lateral hypothalamus. The interest in this relation was initially motivated by the observation that serotonergic antidepressants have therapeutic effects in some anxiety disorders—for example, clomipramine (Anafranil) in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). The effectiveness of buspirone (BuSpar), a serotonin 5-HT1A receptor agonist, in the treatment of anxiety disorders also suggests the possibility of an association between serotonin and anxiety. The cell bodies of most serotonergic neurons are located in the raphe nuclei in the rostral brainstem and project to the cerebral cortex, the limbic system (especially, the amygdala and the hippocampus), and the hypothalamus. Several reports indicate that meta-chlorophenylpiperazine (mCPP), a drug with multiple serotonergic and nonserotonergic effects, and fenfluramine (Pondimin), which causes the release of serotonin, do cause increased anxiety in patients with anxiety disorders; and many anecdotal reports indicate that serotonergic hallucinogens and stimulants—for example, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD) and 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)—are associated with the development of both acute and chronic anxiety disorders in persons who use these drugs. Clinical studies of 5-HT function in anxiety disorders have had mixed results. One study found that patients with panic disorder had lower levels of circulating 5-HT compared with control participants. Thus, no clear pattern of abnormality in 5-HT function in panic disorder has emerged from analysis of peripheral blood elements.

GABA. A role of GABA in anxiety disorders is most strongly supported by the undisputed efficacy of benzodiazepines, which enhance the activity of GABA at the GABA type A (GABAA) receptor, in the treatment of some types of anxiety disorders. Although low-potency benzodiazepines are most effective for the symptoms of generalized anxiety disorder, high-potency benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam (Xanax), and clonazepam are effective in the treatment of panic disorder. Studies in primates have found that autonomic nervous system symptoms of anxiety disorders are induced when a benzodiazepine inverse agonist, β-carboline-3-carboxylic acid (BCCE), is administered. BCCE also causes anxiety in normal control volunteers. A benzodiazepine antagonist, flumazenil (Romazicon), causes frequent severe panic attacks in patients with panic disorder. These data have led researchers to hypothesize that some patients with anxiety disorders have abnormal functioning of their GABAA receptors, although this connection has not been shown directly.

APLYSIA. A neurotransmitter model for anxiety disorders is based on the study of Aplysia californica by Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel, M.D. Aplysia is a sea snail that reacts to danger by moving away, withdrawing into its shell, and decreasing its feeding behavior. These behaviors can be classically conditioned, so that the snail responds to a neutral stimulus as if it were a dangerous stimulus. The snail can also be sensitized by random shocks, so that it exhibits a flight response in the absence of real danger. Parallels have previously been drawn between classic conditioning and human phobic anxiety. The classically conditioned Aplysia shows measurable changes in presynaptic facilitation, resulting in the release of increased amounts of neurotransmitter. Although the sea snail is a simple animal, this work shows an experimental approach to complex neurochemical processes potentially involved in anxiety disorders in humans.

NEUROPEPTIDE Y. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) is a highly conserved 36–amino acid peptide, which is among the most abundant peptides found in mammalian brain. Evidence suggesting the involvement of the amygdala in the anxiolytic effects of NPY is robust, and it probably occurs via the NPY-Y1 receptor. NPY has counterregulatory effects on corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) and LC-NE systems at brain sites that are important in the expression of anxiety, fear, and depression. Preliminary studies in special operations soldiers under extreme training stress indicate that high NPY levels are associated with better performance.

GALANIN. Galanin is a peptide that, in humans, contains 30 amino acids. It has been demonstrated to be involved in a number of physiological and behavioral functions, including learning and memory, pain control, food intake, neuroendocrine control, cardiovascular regulation, and, most recently, anxiety. A dense galanin immunoreactive fiber system originating in the LC innervates forebrain and midbrain structures, including the hippocampus, hypothalamus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Studies in rats have shown that galanin administered centrally modulates anxiety-related behaviors. Galanin and NPY receptor agonists may be novel targets for antianxiety drug development.

Brain Imaging Studies. A range of brain imaging studies, almost always conducted with a specific anxiety disorder, has produced several possible leads in the understanding of anxiety disorders. Structural studies—for example, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)—occasionally show some increase in the size of cerebral ventricles. In one study, the increase was correlated with the length of time patients had been taking benzodiazepines. In one MRI study, a specific defect in the right temporal lobe was noted in patients with panic disorder. Several other brain imaging studies have reported abnormal findings in the right hemisphere but not the left hemisphere; this finding suggests that some types of cerebral asymmetries may be important in the development of anxiety disorder symptoms in specific patients. Functional brain imaging (fMRI) studies—for example, positron emission tomography (PET), single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), and electroencephalography (EEG)—of patients with anxiety disorder have variously reported abnormalities in the frontal cortex; the occipital and temporal areas; and, in a study of panic disorder, the parahippocampal gyrus. Several functional neuroimaging studies have implicated the caudate nucleus in the pathophysiology of OCD. In posttraumatic stress disorder, fMRI studies have found increased activity in the amygdala, a brain region associated with fear (see Color Plate 9.1-1). A conservative interpretation of these data is that some patients with anxiety disorders have a demonstrable functional cerebral pathological condition and that the condition may be causally relevant to their anxiety disorder symptoms.

Genetic Studies. Genetic studies have produced solid evidence that at least some genetic component contributes to the development of anxiety disorders. Heredity has been recognized as a predisposing factor in the development of anxiety disorders. Almost half of all patients with panic disorder have at least one affected relative. The figures for other anxiety disorders, although not as high, also indicate a higher frequency of the illness in first-degree relatives of affected patients than in the relatives of nonaffected persons. Although adoption studies with anxiety disorders have not been reported, data from twin registries also support the hypothesis that anxiety disorders are at least partially genetically determined. Clearly, a linkage exists between genetics and anxiety disorders, but no anxiety disorder is likely to result from a simple mendelian abnormality. One report has attributed about 4 percent of the intrinsic variability of anxiety within the general population to a polymorphic variant of the gene for the serotonin transporter, which is the site of action of many serotonergic drugs. Persons with the variant produce less transporter and have higher levels of anxiety.

In 2005, a scientific team, led by National Institute of Mental Health grantee and Noble Laureate Dr. Eric Kandel demonstrated that knocking out a gene in the brain’s fear hub creates mice unperturbed by situations that would normally trigger instinctive or learned fear responses. The gene codes for stathmin, a protein that is critical for the amygdala to form fear memories. Stathmin knockout mice showed less anxiety when they heard a tone that had previously been associated with a shock, indicating less learned fear. The knockout mice also were more susceptible to explore novel open space and maze environments, a reflection of less innate fear. Kandel suggests that stathmin knockout mice can be used as a model of anxiety states of mental disorders with innate and learned fear components: these animals could be used to develop new antianxiety agents. Whether stathmin is similarly expressed and pivotal for anxiety in the human amygdala remains to be confirmed.

Neuroanatomical Considerations. The locus ceruleus and the raphe nuclei project primarily to the limbic system and the cerebral cortex. In combination with the data from brain imaging studies, these areas have become the focus of much hypothesis-forming about the neuroanatomical substrates of anxiety disorders.

LIMBIC SYSTEM. In addition to receiving noradrenergic and serotonergic innervation, the limbic system also contains a high concentration of GABAA receptors. Ablation and stimulation studies in nonhuman primates have also implicated the limbic system in the generation of anxiety and fear responses. Two areas of the limbic system have received special attention in the literature: increased activity in the septohippocampal pathway, which may lead to anxiety; and the cingulate gyrus, which has been implicated particularly in the pathophysiology of OCD.

CEREBRAL CORTEX. The frontal cerebral cortex is connected with the parahippocampal region, the cingulate gyrus, and the hypothalamus and thus may be involved in the production of anxiety disorders. The temporal cortex has also been implicated as a pathophysiological site in anxiety disorders. This association is based in part on the similarity in clinical presentation and electrophysiology between some patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and patients with OCD.

REFERENCES

Bulbena A, Gago J, Pailhez G, Sperry L, Fullana MA, Vilarroya O. Joint hypermobility syndrome is a risk factor trait for anxiety disorders: A 15-year follow-up cohort study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33:363.

Craske MG, Rauch SL, Ursano R, Prenoveau J, Pine DS, Zinbarg RE. What is an anxiety disorder? Depress Anxiety. 2009;26:1066.

Fergus TA, Valentiner DP, McGrath PB, Jencius S. Shame- and guilt-proneness: Relationships with anxiety disorder symptoms in a clinical sample. J Anxiety Disord. 2010;24:811.

Goodwin RD, Stein DJ. Anxiety disorders and drug dependence: Evidence on sequence and specificity among adults. Psych Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:167.

Kravitz HM, Schott LL, Joffe H, Cyranowski JM, Bromberger JT. Do anxiety symptoms predict major depressive disorder in midlife women? The Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation (SWAN) Mental Health Study (MHS). Psychol Med. 2014:1–10.

McKay D, Storch EA, eds. Handbook of Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety Disorders. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013.

McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: Prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:1027.

Naragon-Gainey K, Gallagher MW, Brown TA. A longitudinal examination of psychosocial impairment across the anxiety disorders. Psycholog Med. 2013;43:1475.

Nebel-Schwalm MS, Davis III TE. Nature and etiological models of anxiety disorders. In: McKay D, Storch EA, eds. Handbook of Treating Variants and Complications in Anxiety Disorders. New York: Springer Science+Business Media; 2013:3.

Pacheco-Unguetti AP, Acosta A, Marqués E, Lupiáñez J. Alterations of the attentional networks in patients with anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2011;25:888.

Pine DS. Anxiety disorders: Introduction and overview. In: Sadock BJ, Sadock VA, Ruiz P, eds. Kaplan & Sadock’s Comprehensive Textbook of Psychiatry. 9th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:1839.

Schanche E. The transdiagnostic phenomenon of self-criticism. Psychotherapy. 2013;50:316.

Shin LM, Davis FC, Van Elzakker MB, Dahlgren MK, Dubois SJ. Neuroimaging predictors of treatment response in anxiety disorders. Bio Mood Anxiety Dis. 2013;3:15.

Stein DJ, Hollander E, Rothbaum BO, eds. Textbook of Anxiety Disorders. 2nd edition. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2009.

Stein DJ, Nesse RM. Threat detection, precautionary responses, and anxiety disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1075.

Taylor S, Abramowitz JS, McKay D. Non-adherence and non-response in the treatment of anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:583.

Uebelacker L, Weisberg R, Millman M, Yen S, Keller M. Prospective study of risk factors for suicidal behavior in individuals with anxiety disorders. Psychological Med. 2013;43:1465.

9.2 Panic Disorder

9.2 Panic Disorder

An acute intense attack of anxiety accompanied by feelings of impending doom is known as panic disorder. The anxiety is characterized by discrete periods of intense fear that can vary from several attacks during one day to only a few attacks during a year. Patients with panic disorder present with a number of comorbid conditions, most commonly agoraphobia, which refers to a fear of or anxiety regarding places from which escape might be difficult.

HISTORY

The idea of panic disorder may have its roots in the concept of irritable heart syndrome, which the physician Jacob Mendes DaCosta (1833–1900) noted in soldiers in the American Civil War. DaCosta’s syndrome included many psychological and somatic symptoms that have since been included among the diagnostic criteria for panic disorder. In 1895, Sigmund Freud introduced the concept of anxiety neurosis, consisting of acute and chronic psychological and somatic symptoms.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

The lifetime prevalence of panic disorder is in the 1 to 4 percent range, with 6-month prevalence approximately 0.5 to 1.0 percent and 3 to 5.6 percent for panic attacks. Women are two to three times more likely to be affected than men, although underdiagnosis of panic disorder in men may contribute to the skewed distribution. The differences among Hispanics, whites, and blacks are few. The only social factor identified as contributing to the development of panic disorder is a recent history of divorce or separation. Panic disorder most commonly develops in young adulthood—the mean age of presentation is about 25 years—but both panic disorder and agoraphobia can develop at any age. Panic disorder has been reported in children and adolescents, and it is probably underdiagnosed in these age groups.

COMORBIDITY

Of patients with panic disorder, 91 percent have at least one other psychiatric disorder. About one-third of persons with panic disorders have major depressive disorder before onset; about two-thirds first experience panic disorder during or after the onset of major depression.

Other disorders also commonly occur in persons with panic disorder. Of persons with panic disorder, 15 to 30 percent also have social anxiety disorder or social phobia, 2 to 20 percent have specific phobia, 15 to 30 percent have generalized anxiety disorder, 2 to 10 percent have PTSD, and up to 30 percent have OCD. Other common comorbid conditions are hypochondriasis or illness anxiety disorder, personality disorders, and substance-related disorders.

ETIOLOGY

Biological Factors

Research on the biological basis of panic disorder has produced a range of findings; one interpretation is that the symptoms of panic disorder are related to a range of biological abnormalities in brain structure and function. Most work has used biological stimulants to induce panic attacks in patients with panic disorder. Considerable evidence indicates that abnormal regulation of brain noradrenergic systems is also involved in the pathophysiology of panic disorder. These and other studies have produced hypotheses implicating both peripheral and central nervous system (CNS) dysregulation in the pathophysiology of panic disorder. The autonomic nervous systems of some patients with panic disorder have been reported to exhibit increased sympathetic tone, to adapt slowly to repeated stimuli, and to respond excessively to moderate stimuli. Studies of the neuroendocrine status of these patients have shown several abnormalities, although the studies have been inconsistent in their findings.

The major neurotransmitter systems that have been implicated are those for norepinephrine, serotonin, and GABA. Serotonergic dysfunction is quite evident in panic disorder, and various studies with mixed serotonin agonist–antagonist drugs have demonstrated increased rates of anxiety. Such responses may be caused by postsynaptic serotonin hypersensitivity in panic disorder. Preclinical evidence suggests that attenuation of local inhibitory GABAergic transmission in the basolateral amygdala, midbrain, and hypothalamus can elicit anxiety-like physiological responses. The biological data have led to a focus on the brainstem (particularly the noradrenergic neurons of the locus ceruleus and the serotonergic neurons of the median raphe nucleus), the limbic system (possibly responsible for the generation of anticipatory anxiety), and the prefrontal cortex (possibly responsible for the generation of phobic avoidance). Among the various neurotransmitters involved, the noradrenergic system has also attracted much attention, with the presynaptic α2-adrenergic receptors, particularly, playing a significant role. Patients with panic disorder are sensitive to the anxiogenic effects of yohimbine in addition to having exaggerated MHPG, cortisol, and cardiovascular responses. They have been identified by pharmacological challenges with the α2-receptor agonist clonidine (Catapres) and the α2-receptor antagonist yohimbine (Yocon), which stimulates firing of the locus ceruleus and elicits high rates of panic-like activity in those with panic disorder.

Panic-Inducing Substances. Panic-inducing substances (sometimes called panicogens) induce panic attacks in most patients with panic disorder and in a much smaller proportion of persons without panic disorder or a history of panic attacks. So-called respiratory panic-inducing substances cause respiratory stimulation and a shift in the acid–base balance. These substances include carbon dioxide (5 to 35 percent mixtures), sodium lactate, and bicarbonate. Neurochemical panic-inducing substances that act through specific neurotransmitter systems include yohimbine, an α2-adrenergic receptor antagonist; mCPP, an agent with multiple serotonergic effects; m-Caroline drugs; GABAB receptor inverse agonists; flumazenil (Romazicon), a GABAB receptor antagonist; cholecystokinin; and caffeine. Isoproterenol (Isuprel) is also a panic-inducing substance, although its mechanism of action in inducing panic attacks is poorly understood. The respiratory panic-inducing substances may act initially at the peripheral cardiovascular baroreceptors and relay their signal by vagal afferents to the nucleus tractus solitarii and then on to the nucleus paragigantocellularis of the medulla. The hyperventilation in patients with panic disorder may be caused by a hypersensitive suffocation alarm system whereby increasing PCO2 and brain lactate concentrations prematurely activate a physiological asphyxia monitor. The neurochemical panic-inducing substances are presumed to primarily affect the noradrenergic, serotonergic, and GABA receptors of the CNS directly.

Brain Imaging. Structural brain imaging studies, for example, MRI, in patients with panic disorder have implicated pathological involvement in the temporal lobes, particularly the hippocampus and the amygdala. One MRI study reported abnormalities, especially cortical atrophy, in the right temporal lobe of these patients. Functional brain imaging studies, for example, positron emission tomography (PET), have implicated dysregulation of cerebral blood flow (smaller increase or an actual decrease in cerebral blood flow). Specifically, anxiety disorders and panic attacks are associated with cerebral vasoconstriction, which may result in CNS symptoms, such as dizziness, and in peripheral nervous system symptoms that may be induced by hyperventilation and hypocapnia. Most functional brain imaging studies have used a specific panic-inducing substance (e.g., lactate, caffeine, or yohimbine) in combination with PET or SPECT to assess the effects of the panic-inducing substance and the induced panic attack on cerebral blood flow.

Mitral Valve Prolapse. Although great interest was formerly expressed in an association between mitral valve prolapse and panic disorder, research has almost completely erased any clinical significance or relevance to the association. Mitral valve prolapse is a heterogeneous syndrome consisting of the prolapse of one of the mitral valve leaflets, resulting in a midsystolic click on cardiac auscultation. Studies have found that the prevalence of panic disorder in patients with mitral valve prolapse is the same as the prevalence of panic disorder in patients without mitral valve prolapse.

Genetic Factors

Various studies have found that the first-degree relatives of patients with panic disorder have a four- to eightfold higher risk for panic disorder than first-degree relatives of other psychiatric patients. The twin studies conducted to date have generally reported that monozygotic twins are more likely to be concordant for panic disorder than are dizygotic twins. At this point, no data exist indicating an association between a specific chromosomal location or mode of transmission and this disorder.

Psychosocial Factors

Psychoanalytic theories have been developed to explain the pathogenesis of panic disorder. Psychoanalytic theories conceptualize panic attacks as arising from an unsuccessful defense against anxiety-provoking impulses. What was previously a mild signal anxiety becomes an overwhelming feeling of apprehension, complete with somatic symptoms.

Many patients describe panic attacks as coming out of the blue, as though no psychological factors were involved, but psychodynamic exploration frequently reveals a clear psychological trigger for the panic attack. Although panic attacks are correlated neurophysiologically with the locus ceruleus, the onset of panic is generally related to environmental or psychological factors. Patients with panic disorder have a higher incidence of stressful life events (particularly loss) than control subjects in the months before the onset of panic disorder. Moreover, the patients typically experience greater distress about life events than control subjects do.

The hypothesis that stressful psychological events produce neurophysiological changes in panic disorder is supported by a study of female twins. Separation from the mother early in life was clearly more likely to result in panic disorder than was paternal separation in the cohort of 1,018 pairs of female twins. Another etiological factor in adult female patients appears to be childhood physical and sexual abuse. Approximately 60 percent of women with panic disorder have a history of childhood sexual abuse compared with 31 percent of women with other anxiety disorders. Further support for psychological mechanisms in panic disorder can be inferred from a study of panic disorder in which patients received successful treatment with cognitive therapy. Before the therapy, the patients responded to panic attack induction with lactate. After successful cognitive therapy, lactate infusion no longer produced a panic attack.

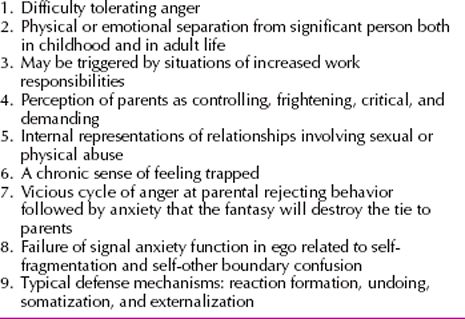

The research indicates that the cause of panic attacks is likely to involve the unconscious meaning of stressful events and that the pathogenesis of the panic attacks may be related to neurophysiological factors triggered by the psychological reactions. Psychodynamic clinicians should always thoroughly investigate possible triggers whenever assessing a patient with panic disorder. The psychodynamics of panic disorder are summarized in Table 9.2-1.

Table 9.2-1

Table 9.2-1

Psychodynamic Themes in Panic Disorder

DIAGNOSIS

Panic Attacks

A panic attack is a sudden period of intense fear or apprehension that may last from minutes to hours. Panic attacks can occur in mental disorders other than panic disorder, particularly in specific phobia, social phobia, and PTSD. Unexpected panic attacks occur at any time and are not associated with any identifiable situational stimulus, but panic attacks need not be unexpected. Attacks in patients with social and specific phobias are usually expected or cued to a recognized or specific stimulus. Some panic attacks do not fit easily into the distinction between unexpected and expected, and these attacks are referred to as situationally predisposed panic attacks. They may or may not occur when a patient is exposed to a specific trigger, or they may occur either immediately after exposure or after a considerable delay.

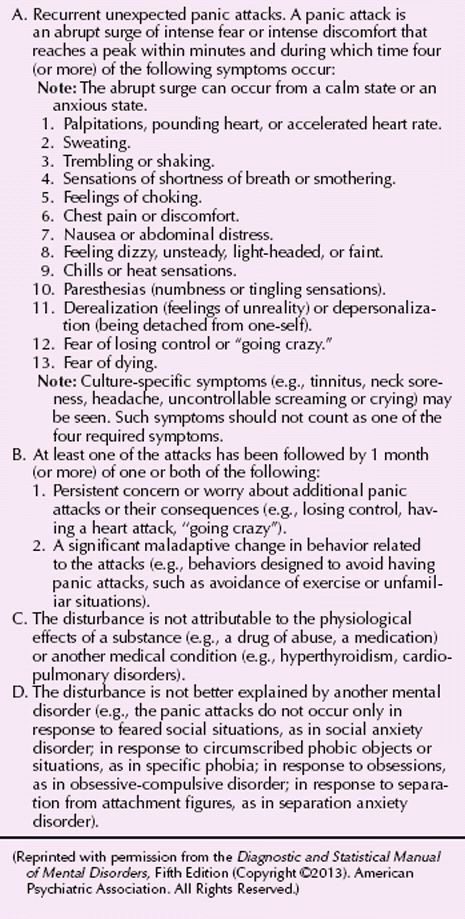

Panic Disorder

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) diagnostic criteria for panic disorder are listed in Table 9.2-2. Some community surveys have indicated that panic attacks are common, and a major issue in developing diagnostic criteria for panic disorder was determining a threshold number or frequency of panic attacks required to meet the diagnosis. Setting the threshold too low results in the diagnosis of panic disorder in patients who do not have an impairment from an occasional panic attack; setting the threshold too high results in a situation in which patients who are impaired by their panic attacks do not meet the diagnostic criteria.

Table 9.2-2

Table 9.2-2

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria for Panic Disorder

CLINICAL FEATURES

The first panic attack is often completely spontaneous, although panic attacks occasionally follow excitement, physical exertion, sexual activity, or moderate emotional trauma. Clinicians should attempt to ascertain any habit or situation that commonly precedes a patient’s panic attacks. Such activities may include the use of caffeine, alcohol, nicotine, or other substances; unusual patterns of sleeping or eating; and specific environmental settings, such as harsh lighting at work.

The attack often begins with a 10-minute period of rapidly increasing symptoms. The major mental symptoms are extreme fear and a sense of impending death and doom. Patients usually cannot name the source of their fear; they may feel confused and have trouble concentrating. The physical signs often include tachycardia, palpitations, dyspnea, and sweating. Patients often try to leave whatever situation they are in to seek help. The attack generally lasts 20 to 30 minutes and rarely more than an hour. A formal mental status examination during a panic attack may reveal rumination, difficulty speaking (e.g., stammering), and impaired memory. Patients may experience depression or depersonalization during an attack. The symptoms can disappear quickly or gradually. Between attacks, patients may have anticipatory anxiety about having another attack. The differentiation between anticipatory anxiety and generalized anxiety disorder can be difficult, although patients with pain disorder with anticipatory anxiety can name the focus of their anxiety.

Somatic concerns of death from a cardiac or respiratory problem may be the major focus of patients’ attention during panic attacks. Patients may believe that the palpitations and chest pain indicate that they are about to die. As many as 20 percent of such patients actually have syncopal episodes during a panic attack. The patients may be seen in emergency departments as young (20s), physically healthy persons who nevertheless insist that they are about to die from a heart attack. Rather than immediately diagnosing hypochondriasis, the emergency department physician should consider a diagnosis of panic disorder. Hyperventilation can produce respiratory alkalosis and other symptoms. The age-old treatment of breathing into a paper bag sometimes helps because it decreases alkalosis.

Mrs. K was a 35-year-old woman who initially presented for treatment at the medical emergency department at a large university-based medical center. She reported that while sitting at her desk at her job, she had suddenly experienced difficulty breathing, dizziness, tachycardia, shakiness, and a feeling of terror that she was going to die of a heart attack. A colleague drove her to the emergency department, where she received a full medical evaluation, including electrocardiography and routine blood work, which revealed no sign of cardiovascular, pulmonary, or other illness. She was subsequently referred for psychiatric evaluation, where she revealed that she had experienced two additional episodes over the past month, once when driving home from work and once when eating breakfast. However, she had not presented for medical treatment because the symptoms had resolved relatively quickly each time, and she worried that if she went to the hospital without ongoing symptoms, “people would think I’m crazy.” Mrs. K reluctantly took the phone number of a local psychiatrist but did not call until she experienced a fourth episode of a similar nature. (Courtesy of Erin B. McClure-Tone, Ph.D., and Daniel S. Pine, M.D.)

Associated Symptoms

Depressive symptoms are often present in panic disorder, and in some patients, a depressive disorder coexists with the panic disorder. Some studies have found that the lifetime risk of suicide in persons with panic disorder is higher than it is in persons with no mental disorder. Clinicians should be alert to the risk of suicide. In addition to agoraphobia, other phobias and OCD can coexist with panic disorder. The psychosocial consequences of panic disorder, in addition to marital discord, can include time lost from work, financial difficulties related to the loss of work, and alcohol and other substance abuse.

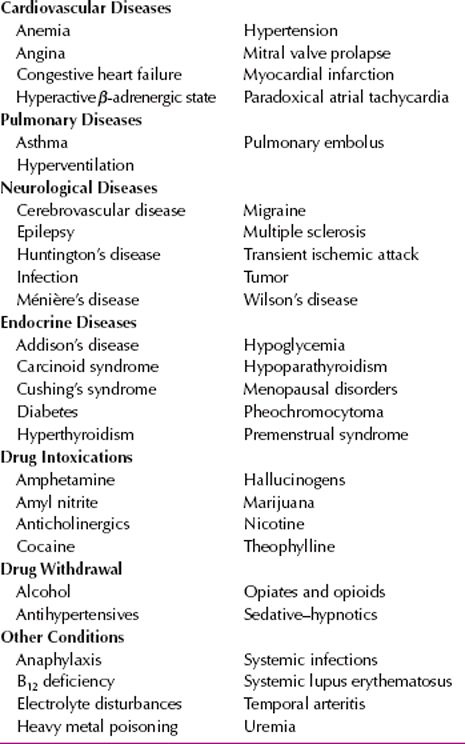

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Panic Disorder

The differential diagnosis for a patient with panic disorder includes many medical disorders (Table 9.2-3), as well as many mental disorders.

Table 9.2-3

Table 9.2-3

Organic Differential Diagnosis for Panic Disorder

Medical Disorders

Panic disorder must be differentiated from a number of medical conditions that produce similar symptomatology. Panic attacks are associated with a variety of endocrinological disorders, including both hypo- and hyperthyroid states, hyperparathyroidism, and pheochromocytomas. Episodic hypoglycemia associated with insulinomas can also produce panic-like states, as can primary neuropathological processes. These include seizure disorders, vestibular dysfunction, neoplasms, or the effects of both prescribed and illicit substances on the CNS. Finally, disorders of the cardiac and pulmonary systems, including arrhythmias, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and asthma, can produce autonomic symptoms and accompanying crescendo anxiety that can be difficult to distinguish from panic disorder. Clues of an underlying medical etiology to panic-like symptoms include the presence of atypical features during panic attacks, such as ataxia, alterations in consciousness, or bladder dyscontrol; onset of panic disorder relatively late in life; and physical signs or symptoms indicative of a medical disorder.

Mental Disorders

Panic disorder also must be differentiated from a number of psychiatric disorders, particularly other anxiety disorders. Panic attacks occur in many anxiety disorders, including social and specific phobia, Panic may also occur in PTSD and OCD. The key to correctly diagnosing panic disorder and differentiating the condition from other anxiety disorders involves the documentation of recurrent spontaneous panic attacks at some point in the illness. Differentiation from generalized anxiety disorder can also be difficult. Classically, panic attacks are characterized by their rapid onset (within minutes) and short duration (usually less than 10 to 15 minutes), in contrast to the anxiety associated with generalized anxiety disorder, which emerges and dissipates more slowly. Making this distinction can be difficult, however, because the anxiety surrounding panic attacks can be more diffuse and slower to dissipate than is typical. Because anxiety is a frequent concomitant of many other psychiatric disorders, including the psychoses and affective disorders, discrimination between panic disorder and a multitude of disorders can also be difficult.

Specific and Social Phobias

Sometimes it is difficult to distinguish between panic disorder, on the one hand, and specific and social phobias, on the other hand. Some patients who experience a single panic attack in a specific setting (e.g., an elevator) may go on to have long-lasting avoidance of the specific setting, regardless of whether they ever have another panic attack. These patients meet the diagnostic criteria for a specific phobia, and clinicians must use their judgment about what is the most appropriate diagnosis. In another example, a person who experiences one or more panic attacks may then fear speaking in public. Although the clinical picture is almost identical to the clinical picture in social phobia, a diagnosis of social phobia is excluded because the avoidance of the public situation is based on fear of having a panic attack rather than on fear of the public speaking itself.

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS

Panic disorder usually has its onset in late adolescence or early adulthood, although onset during childhood, early adolescence, and midlife does occur. Some data implicate increased psychosocial stressors with the onset of panic disorder, although no psychosocial stressor can be definitely identified in most cases.

Panic disorder, in general, is a chronic disorder, although its course is variable, both among patients and within a single patient. The available long-term follow-up studies of panic disorder are difficult to interpret because they have not controlled for the effects of treatment. Nevertheless, about 30 to 40 percent of patients seem to be symptom free at long-term follow-up, about 50 percent have symptoms that are sufficiently mild not to affect their lives significantly, and about 10 to 20 percent continue to have significant symptoms.

After the first one or two panic attacks, patients may be relatively unconcerned about their condition; with repeated attacks, however, the symptoms may become a major concern. Patients may attempt to keep the panic attacks secret and thereby cause their families and friends concern about unexplained changes in behavior. The frequency and severity of the attacks can fluctuate. Panic attacks can occur several times in a day or less than once a month. Excessive intake of caffeine or nicotine can exacerbate the symptoms.

Depression can complicate the symptom picture in anywhere from 40 to 80 percent of all patients, as estimated by various studies. Although the patients do not tend to talk about suicidal ideation, they are at increased risk for committing suicide. Alcohol and other substance dependence occurs in about 20 to 40 percent of all patients, and OCD may also develop. Family interactions and performance in school and at work commonly suffer. Patients with good premorbid functioning and symptoms of brief duration tend to have good prognoses.

TREATMENT

With treatment, most patients exhibit dramatic improvement in the symptoms of panic disorder and agoraphobia. The two most effective treatments are pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy. Family and group therapy may help affected patients and their families adjust to the patient’s disorder and to the psychosocial difficulties that the disorder may have precipitated.

Pharmacotherapy

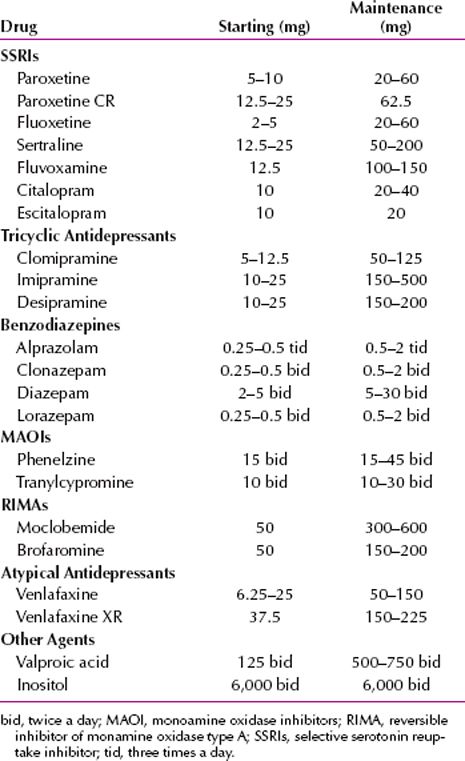

Overview. Alprazolam (Xanax) and paroxetine (Paxil) are the two drugs approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of panic disorder. In general, experience is showing superiority of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and clomipramine (Anafranil) over the benzodiazepines, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and tricyclic and tetracyclic drugs in terms of effectiveness and tolerance of adverse effects. Some reports have suggested a role for venlafaxine (Effexor), and buspirone (BuSpar) has been suggested as an additive medication in some cases. Venlafaxine is approved by the FDA for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder and may be useful in panic disorder combined with depression. β-adrenergic receptor antagonists have not been found to be particularly useful for panic disorder. A conservative approach is to begin treatment with paroxetine, sertraline (Zoloft), citalopram (Celexa), or fluvoxamine (Luvox) in isolated panic disorder. If rapid control of severe symptoms is desired, a brief course of alprazolam should be initiated concurrently with the SSRI followed by slowly tapering use of the benzodiazepine. In long-term use, fluoxetine (Prozac) is an effective drug for panic with comorbid depression, although its initial activating properties may mimic panic symptoms for the first several weeks, and it may be poorly tolerated on this basis. Clonazepam (Klonopin) can be prescribed for patients who anticipate a situation in which panic may occur (0.5 to 1 mg as required). Common dosages for antipanic drugs are listed in Table 9.2-4.

Table 9.2-4

Table 9.2-4

Recommended Dosages for Antipanic Drugs (Daily Unless Indicated Otherwise)

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree