Anxiety Disorders in Epilepsy

Cynthia L. Harden

Martin A. Goldstein

Alan B. Ettinger

Although affective and thought disorders have received extensive attention, anxiety remains a lesser studied psychiatric aspect of epilepsy, despite its clinical importance and a corresponding intensification of its study within psychiatry. This chapter discusses the relationship between epilepsy and anxiety, the manifestations of anxiety in persons with epilepsy, its significance, and treatment.

The Evolutionary Significance of Anxiety

As epilepsy represents a model phenomenon in the history of the relationship between neurology and psychiatry, anxiety is a model phenomenon in the history of the relationship between mind and brain. Anxiety is the quintessential example of a phenomenon belonging to both psychological and neurophysiological domains (1). It is worthwhile to consider anxiety within the context of that theoretical glue that provides ultimate coherence to all biologic theorizing, that is, evolution.

As Hofer observes, of all internal experiences, “anxiety may be the one with the closest parallels in other species and with the most ancient evolutionary heritage” (2). Indeed, anxiety is a predictable product of natural selection, which depends on danger avoidance capacity so much that components of the experience that we call anxiety have long been integrated into the neurocircuitry of even primitive organisms (2). An evolutionary perspective can facilitate definition of the core meaning of anxiety: a means to detect signals, a way to discriminate those that denote danger, and the capacity to initiate phylogenetically derived and ontogenically learned behavior that results in avoidance of that danger. As evolution progressed, externally directed danger-sensing mechanisms eventually developed the capacity so that it could be directed inward for signaling internal danger as well (1). The competitive survival advantage bestowed by the capacity to anticipate danger, both internal and external, and react on the basis of prior experience, nurtured the evolutionary development of relevant cognitive functions (e.g., memory) and their connections through corticolimbic circuits to affective, autonomic, neuroendocrine, and neuroimmune response systems underlying the generation of anxiety (1). Therefore,

anxiety is a neuropsychiatric characteristic of our evolutionary history.

anxiety is a neuropsychiatric characteristic of our evolutionary history.

Given anxiety’s evolutionary heritage, it is appropriate to assume that the concept of anxiety as an adaptive reaction to the perception of danger originated with Darwin (Breur and Freud both cite Darwin as the source of their insight that “emotional expression consists of actions which originally had a meaning and served a purpose”) (3). According to Darwin, “If we expect to suffer we are anxious, if we have no hope of relief, we despair” (4). In addition to foreshadowing by a century the contemporary interest in a link between anxiety and depressive disorders, this view highlights the relevance of learned helplessness models for interpreting the affective impact of seizure occurrence in an individual patient.

Deriving from their evolutionary origins and their behavioral and experiential qualities, anxiety and fear are closely related concepts, with a history of somewhat arbitrary distinctions. In psychology literature, fear is often defined as a response to a threat that is known, external, definite, or nonconflictual in origin; anxiety is in response to a threat that is unknown, internal, vague, or conflictual in origin. But it is not that clear whether the psychodynamic distinction between fear and anxiety arose by accident: Freud’s early translator mistranslated “angst,” the German word for fear, as anxiety (5). Moreover, current interdisciplinary studies investigating the neurobiology of anxiety are based on animal models of the neurocircuitry of fear (6). In sum, the distinction between anxiety and fear remains vague; demarcation based on the acuteness and definability of the threat continues to operate in the literature.

Nosology

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) classifies anxiety disorders as a distinct category of axis I disorders (7). This group includes generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder (with and without agoraphobia), obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD), post-traumatic stress disorder, and phobias. The class also includes the diagnosis “anxiety disorder due to a medical condition,” applied when anxiety exists as a direct physiological consequence of another identified pathophysiological process. Anxiety in patients with epilepsy can potentially fall into any of these diagnoses, and varying permutations of anxiety type combinations can exist within any individual patient.

Theories of Pathological Anxiety

Psychodynamic Theory: In 1895, Freud theorized in Obsessions and Phobias that the syndrome of “anxiety hysteria” (consisting of conversion symptoms and phobias) had a psychological etiology as a response to the threatened recrudescence of unpleasant emotions linked to unacceptable sexual memories (8). With the publication of Inhibitions, Symptoms, and Anxiety in 1926, Freud formulated a new dual theory of anxiety genesis as secondary to (a) obstruction of libidinal discharge, thereby having a biological basis; or (b) intrapsychic conflict (e.g., an unacceptable drive/repressed wish pressing for conscious representation and discharge), therefore having a psychological basis (9). As Freud’s “energy”-based theories faded, the fundamental function of anxiety within psychoanalytical theory eventually operationalized as an unconscious warning, known as signal anxiety, which prompts mobilization of ego resources to avert danger. Psychodynamically, anxiety can signify real or imagined threat to personal security, identity, reality-organizing framework, or vital object relations (e.g., crucial relationships) (10). In the post-Freudian pluralistic environment, alternative perspectives employ anxiety in different ways to fit each theoretical variation, but all of them continue to regard anxiety to be of equal importance (11).

Learning and Cognitive-Behavioral Theory: Building on the concepts of Pavlovian conditioning, Watson (considered the father of American behaviorism) believed anxiety was largely explainable as a form of conditioned response (12). By the 1950s, the resemblance between human anxiety and experimentally induced “anxiety” in stressed laboratory animals was recognized, setting the stage for the development of cognitive therapy by Ellis and Beck in the 1960s and 1970s, respectively (13,14). Briefly, the cognitive theory of anxiety posits that faulty, distorted thought patterns contribute to symptom production. Patients with anxiety disorders overestimate the degree of danger and the probability of harm in a given situation while underestimating their abilities to cope with perceived threats (5). Patients with panic disorder can experience thoughts of loss of control and fear of dying that follow physiological sensations (e.g., palpitations, tachycardia, and light-headedness) (5).

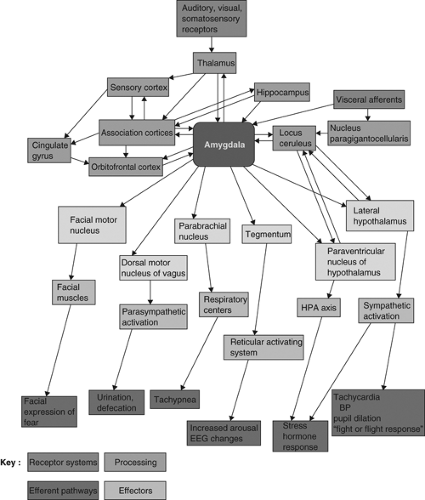

Neurobiological Theory: Multiple studies of neurochemical, neuroanatomical, neuroendocrinological, and functional neuroimaging are attempting to establish a unified field, neurobiology of anxiety. These investigations have contributed to the synthesis of anxiety circuitry schematics such as those in Figure 14.1 (15,16).

As seen earlier, central to the anxiety model of most theorists is the amygdala, hypothesized to be the key structure integrating interoceptive and exteroceptive stimuli and distributing processed afferent data to the multiple efferent systems (cortical, limbic, basal ganglia, hypothalamic, brainstem) that produce the autonomical, affective, cognitive, and endocrinological components of the anxiety response. Seizures, regardless of type and magnitude, represent an acute fundamental disruption to neuropsychiatric homeostasis, thereby necessarily impacting this circuitry. Therefore, seizures, especially those with limbic involvement, can hijack this system, giving rise to anxiety. Complex mechanisms mediating the connection between seizures and anxiety, including kindling and other neuroplastic processes affecting anxiety/fear circuits, are the targets of intense study. Further details about potential biological etiologies for anxiety in epilepsy are found in the appendix to this chapter.

Temporal Relationship of Anxiety to Seizures

Like other psychiatric phenomena, anxiety can be temporally related to epilepsy in one or more of the following ways:

As an ictal phenomenon (i.e., anxiety as seizure or a seizure component)

As a simple partial seizure alone

As an aura component of a complex seizure

As a preictal phenomenon

As a secondary neuropsychiatric aftereffect of seizure—that is, a postictal event

As an interictal phenomenon (discussed in following section)

Ictal Anxiety

Seizure activity can produce experiential symptoms and behavioral manifestations that are indistinguishable from a primary anxiety disorder. Fear is a common aura feature, and may at times mimic panic attacks. Among patients with partial seizure, fear is reported as an aura in up to 15% of patients (17), and several studies have shown fear to be the most common ictal emotion in patients with epilepsy (18). Young, Chandarana et al. reported five patients with brief simple partial seizures mimicking panic disorder (19). All of these patients had mesial temporal structural lesions associated with intractable epilepsy. Features distinguishing seizures from panic attacks in these patients included briefer duration and greater stereotypy (19).

Fear and anxiety are common symptoms in electrically induced simple partial seizures (20). Anteromedial temporal seizures and cingulate seizures, in particular,

can cause symptoms varying from mild unease to horror (20). A report on the presurgical localization of eight patients for whom fear was the main symptom of their seizures suggests no clear lateralization for ictal fear. Seizure localization was right temporal in three patients, left temporal in three, bitemporal in one, and frontal in one. On the basis of stereotactic chronic depth electrode recordings in four of these eight patients, generation of ictal fear involves a network consisting of orbitoprefrontal, anterior cingulate, and temporal limbic cortices. In six patients, a cortical resection was performed with an Engel’s class 1 outcome, which implies the patients are seizure-free, though

simple partial seizures that do not disable them may persist (21). Indeed, ictal fear may signify well-localized anterior temporal epilepsy and may be associated with a more favorable surgical outcome than in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) but without ictal fear (22).

can cause symptoms varying from mild unease to horror (20). A report on the presurgical localization of eight patients for whom fear was the main symptom of their seizures suggests no clear lateralization for ictal fear. Seizure localization was right temporal in three patients, left temporal in three, bitemporal in one, and frontal in one. On the basis of stereotactic chronic depth electrode recordings in four of these eight patients, generation of ictal fear involves a network consisting of orbitoprefrontal, anterior cingulate, and temporal limbic cortices. In six patients, a cortical resection was performed with an Engel’s class 1 outcome, which implies the patients are seizure-free, though

simple partial seizures that do not disable them may persist (21). Indeed, ictal fear may signify well-localized anterior temporal epilepsy and may be associated with a more favorable surgical outcome than in patients with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) but without ictal fear (22).

The association of ictal fear with amygdalar dysfunction was explored by comparing fear recognition using tests of visual and face processing as well as emotion recognition and social judgement in three groups of patients; 13 with TLE and ictal fear, 14 with TLE and nonfear auras, and 10 with idiopathic generalized epilepsy (IGE). All three epilepsy groups had fear recognition deficits, but the group with ictal fear had relatively greater impairment, suggesting that social cognition deficits are present in epilepsy, particularly TLE (23).

Preictal Anxiety

Patients frequently complain of increased anxiety and hyperactivity in the days or hours before a seizure. In one study of patients with mixed types of epilepsies, mood and anxiety scales worsened in the days before a seizure, with an improvement after seizure occurrence (24). This interesting phenomenon remains incompletely explored.

Postictal Anxiety

Postictal mood and anxiety changes have been evaluated most thoroughly in a survey of postictal characteristics of 100 consecutive patients with refractory partial epilepsy (25). Postictal psychiatric symptoms (present in at least half of the seizure occurrences for each patient) included anxiety symptoms as the most frequent postictal psychiatric alteration, occurring in 45 patients, compared with depressive symptoms in 43 patients. Postictal anxiety included worry, agoraphobic symptoms, and panic feelings. The duration of psychiatric symptoms was 24 hours on average. A psychiatric history and a seizure frequency of less than one per month were predictive of postictal depression and anxiety, prompting the authors to speculate that these are the psychiatric equivalent of a postictal Todd’s paralysis phenomenon.

Interictal Anxiety Symptoms in Patients with Epilepsy

Anxiety symptoms are reported in as many as 66% of patients with epilepsy (17). Although most frequently found among patients with partial seizures related to limbic foci, investigators have also observed an increased rate of anxiety symptoms among patients with generalized epilepsy (20). Multiple theories have been proposed to explain interictal anxiety. Two major psychological mechanisms suggested are fear of seizure recurrence (“seizure phobia”) and issues surrounding locus of control, a major concept derived from depression theory. Surprisingly, documented cases of actual seizure phobia are relatively rare (26). In contrast, problems related to a sense of dispersed locus of control can be profound in patients with epilepsy, potentially giving rise to discrete panic attacks or persistent generalized anxiety disorder (27). Connections to learned helplessness models of depression also become relevant. Putative neurobiological mechanisms underlying a direct connection between seizures and at least some forms of interictal anxiety are multiple and complex, as can easily be appreciated when considering the multiple components of the neurobiological pathways mentioned earlier that can be impacted by almost any form of epilepsy.

Responding to anecdotal case reports, and the successful use of electroconvulsive therapy to treat some anxiety disorders (28), Goldstein et al. performed a study of the relationship between seizure frequency and anxiety using the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS). They found the surprisingly counterintuitive result that among 80 adult patients with partial epilepsy experiencing persistent breakthrough seizures, relatively

high seizure frequency is associated with lower anxiety levels than relatively low seizure frequencies (29). Seventy-one of 80 patients had at least one seizure per month and 9 had less-frequent seizures. This finding is consistent with the finding by Kanner et al. (25) that postictal anxiety symptoms occur more reliably in patients with seizure frequencies of less than one per month. A simplified interpretation of these results would take us back to Darwin (and Canetti and Hitchcock): do frequent seizures actually reduce the anxiety attendant upon the anticipation of a seizure? It is possible that anxiety-generating neurocircuitry and psychological mechanisms “habituate” to higher seizure frequencies, processing events such as “routine” and thereby making anxiety generation less adaptive, or perhaps this relationship is simply related to the underlying learned helplessness.

high seizure frequency is associated with lower anxiety levels than relatively low seizure frequencies (29). Seventy-one of 80 patients had at least one seizure per month and 9 had less-frequent seizures. This finding is consistent with the finding by Kanner et al. (25) that postictal anxiety symptoms occur more reliably in patients with seizure frequencies of less than one per month. A simplified interpretation of these results would take us back to Darwin (and Canetti and Hitchcock): do frequent seizures actually reduce the anxiety attendant upon the anticipation of a seizure? It is possible that anxiety-generating neurocircuitry and psychological mechanisms “habituate” to higher seizure frequencies, processing events such as “routine” and thereby making anxiety generation less adaptive, or perhaps this relationship is simply related to the underlying learned helplessness.

A recent assessment of the prevalence of anxiety symptoms in patients with epilepsy was reported in 201 subjects using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. The investigators found that 48% of subjects reported at least mild anxiety symptoms (25% mild, 16% moderate, and 7% severe) (30). Interestingly, anxiety symptoms were more prevalent than depressive symptoms, which were reported in 38% of subjects.

Depression and anxiety symptoms were measured in 281 adult persons with epilepsy and compared with a control group without epilepsy, using Goldberg’s Anxiety and Depression scale (31). This study, performed in West Africa, showed that the epilepsy group had significantly higher depression and anxiety scores than controls and the scores correlated with higher seizure frequency and lack of treatment.

Another evaluation of anxiety compared patients with epilepsy with nonepileptic control subjects using the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) (32). They found higher trait anxiety scores in the epileptic group compared with normal controls. In addition, the investigators found that a briefer duration (<2 years) of symptomatic epilepsy was associated with higher anxiety levels (32).

Effect of Anxiety on Quality of Life in Epilepsy

Quality of life in epilepsy is recognized to be highly correlated with depressive symptoms and depression is likely the most powerful predictor of quality of life in epilepsy (33). However, anxiety symptoms, as previously discussed, are more frequent than depressive symptoms and two studies show that anxiety has an independent and significant effect on quality of life in epilepsy (30,34). In both these reports, depression and anxiety had greater effect on quality of life scores than epilepsy-related factors, such as seizure frequency or epilepsy duration.

Anxiety in Children with Epilepsy

Several studies have evaluated anxiety in children with epilepsy. The occurrence of depression and anxiety in a large group of children aged 5 to 16 years with complex partial seizures (n = 100) was compared with that in similar-sized groups of both children with childhood absence epilepsy and normal children (35). Children with complex partial seizures and childhood absence epilepsy were five times as likely to have an affective or anxiety disorder than normal controls. Within the epilepsy group, children with absence epilepsy were more likely to have an anxiety disorder alone than children with complex partial seizures, who were more likely to have comorbid depression with anxiety and depression alone. Anxiety and affective disorders occurred in 33% of the epilepsy group; further, anxiety disorder was the most frequent diagnosis among children with suicidal ideation.

Panic Disorder in Epilepsy

Panic disorder is often considered in the differential diagnosis of partial seizures, owing to the overlap of symptoms. Clinical features can aid in differentiating the two entities. The age of onset for panic disorder is usually between 20 and 30 years, and consciousness is preserved during the event. Further, as with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, the duration of the panic episode can be longer than a typical seizure, from minutes to hours, and there should be no postictal confusion. However, the clinical expression of panic disorder and partial seizures can have nearly identical symptoms, leading to a risk of misdiagnosis for either illness.

The rate of potential misdiagnosis of epilepsy as panic disorder can be estimated by the report detailed in the following text. In a series of 112 consecutive patients with intractable TLE, 5 patients were identified whose seizures had been previously diagnosed as panic attacks (38). The ictal phenomenon in these five patients included feelings of panic and impending doom, hyperventilation, palpitations, diaphoresis, shortness of breath, and generalized paresthesiae. Ictal panic was not present in 72 patients with extratemporal epilepsy, and further, the 5 patients with ictal panic all had right mid or anterior temporal localization.

Of course, panic disorder and TLE can coexist in the same patient, each requiring a specific treatment (39).

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in Epilepsy

OCD is characterized by recurrent obsessions or compulsions that are excessive, consuming, and dysfunctional. Forced thinking as an example of a compulsion is not uncommon as an ictal phenomenon, and compulsive behaviors as preictal, ictal, or postictal occurrences have been reported. A recent study of OCD in patients with epilepsy is the first report to link OCD with TLE (40). A comprehensive psychiatric evaluation, specifically evaluating for the presence of OCD symptoms, of 62 patients with TLE, 20 patients with IGE, and 82 matched healthy controls revealed that 9 of the patients with TLE, none of the idiopathic generalized patients, and 1 control subject had OCD. There was no difference in epilepsy-related factors, such as epilepsy duration or localization, in patients with TLE who have OCD and patients with TLE who do not have OCD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree