36

36

Are There New Therapies That Improve Outcome in Spinal Cord—Injured Patients?

BRIEF ANSWER

Despite a report of beneficial effects of GM1 ganglioside in a small study of spinal cord-injured patients, a larger trial found no significant effect according to the main outcome measure. Secondary analyses in that trial suggested some benefit from administration of GM1 ganglioside, including a more rapid rate of recovery. In terms of other therapies, clinical trials have failed to demonstrate benefit from thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) or from nimodipine, but the small numbers of patients in those studies may have contributed to a masking of any beneficial effects.

Background

Although prevention remains the most effective intervention for spinal cord injury (SCI), attempts to diminish and/or reverse damage to the injured spinal cord have been proceeding for decades. The many different research approaches that have been explored include pharmacologic therapies and, more recently, transplantation of fetal neural tissue. Several pharmacologic treatments have been tested in large clinical studies.

Literature Review

Prehospital Care

With the development of the 19-center National Spinal Cord Injury Database between 1973 and 1985, national data on SCI were collected in a central data repository for the first time.1 This effort catalyzed the creation of regional centers for the treatment of SCI. Such projects also provided impetus for protocol-driven prehospital care and for triage systems that directly transported patients with SCI to definitive care facilities specializing in the treatment of these patients.

Improvements in prehospital diagnosis, initial fluid and airway management, immobilization, and rapid transportation could well be responsible for most of the improvement in outcomes of SCI patients during the last decade. For example, a recently conducted multicenter trial that enrolled patients with a significant SCI documented that 61.7% were taken to a local emergency room for stabilization and initial medical assessment before transfer to a definitive spinal care facility (class II data).2 This process necessitates a second transport, prolonged immobilization, and consequent delay of such treatments as traction and spinal stabilization (which are often not performed at the initial hospital). Working with local prehospital care providers to improve the percentage of SCI patients who are initially transported to a definitive facility could be a big step toward improving the ultimate outcome of many patients.

Pearl

Improvements in prehospital care could well be responsible for most of the improvement in outcomes of SCI patients in recent years.

Pharmacologic Therapy

To date, at least eight prospective drug trials have investigated pharmacologic therapies for acute SCI in humans.3–11 These trials can be divided into three groups: those investigating methylprednisolone sodium succinate (MPSS),3–6 those evaluating Sygen (GM1 ganglioside),7–9 and the smaller pilot studies of TRH10 and nimodipine.11

Studies that enrolled patients in the 1980s include the first National Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study (NASCIS 1),3 NASCIS 2,4 and the Maryland GM1 Ganglioside Study.7,8 These studies were followed by two additional studies in the 1990s: NASCIS 35 and the multicenter Sygen (GM1 ganglioside) study.9 (The NASCIS studies are discussed in Chapter 35.)

The Maryland GM1 Ganglioside Study

Gangliosides are complex acidic glycolipids located in cell membranes of mammals. They are especially abundant in the membranes of central nervous system cells. Acute neuroprotective and longer-term regenerative effects have been reported in multiple experimental studies of ischemia and injury. Clinical trials have investigated the efficacy of gangliosides in stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and other entities. Proposed mechanisms of action include antiexcitotoxic effects, prevention of apoptosis, and enhancement of neuroreintegration. In terms of SCI, one possible mechanism of recovery may be enhancement of function or potency of the damaged white matter passing through the level of the injury, thus facilitating increased function at caudal neurologic levels. Another possibility is that gangliosides may increase the survival of axons at the injury site or augment the response of neurons in the conus to decreased input from the damaged white matter tracts passing through the injury site.9,12,13

A single-center trial of monosialotetrahexosylganglioside (GM1 ganglioside) in acute SCI enrolled patients from January 1986 to May 1987 at the Maryland Institute for Emergency Medical Services Systems in Baltimore, Maryland. Results were reported in 1991.7,8 This prospective double-blind study randomized 37 patients, 34 of whom (23 with cervical injuries and 11 with thoracic injuries) completed the investigational protocol of either placebo or 100 mg of intravenous GM1 ganglioside daily for a planned 30-day treatment period, with the first dose administered within 72 hours of injury. All patients received a course of methylprednisolone therapy at a dose of approximately one-tenth the NASCIS 2 dose recommendation. (The results of NASCIS 2 were not reported until after the completion of patient entry into the Maryland study.)

The American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) motor score7 and the Frankel scale7,14 were used to assess neurologic status at baseline and at follow-up. The results of the Maryland study demonstrated a significant treatment effect on the distribution of improvement of Frankel grades from baseline to 1-year follow-up (p =.034) (class I data). However, differences in improvement in ASIA motor score were not statistically significant. (The original article reported significance in this measure, but a subsequent clarification8 reported that the previously described significant improvement in total ASIA motor score actually referred to the motor score for the lower extremities alone.) This small study provided the foundation for the subsequent multicenter study of GM1 ganglioside in acute SCI.

Pearl

The Maryland study demonstrated a significant effect of ganglioside treatment in terms of Frankel grades, but improvement in ASIA motor scores was not statistically significant.

Sygen Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study

Sygen is a proprietary name for GM1 ganglioside produced by the Fidia Pharmaceutical Corporation, Washington, D.C., which sponsored the study. The Sygen Multicenter Acute Spinal Cord Injury Study2,9,15 was designed to determine the efficacy and safety of Sygen in the treatment of patients with acute SCI following standard treatment with MPSS.

Study Design

Patients in this prospective, double-blind, randomized trial were stratified into six groups by level (cervical or thoracic) and by baseline severity [ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) grade of A, B, or combined CD] and randomized into three parallel treatment groups: placebo, low-dose Sygen, or high-dose Sygen. All groups received a bolus dose followed by 56 days of study treatment. The low-dose Sygen group received a 300-mg loading dose followed by 100 mg/day for 56 days, and the high-dose group received a 600-mg loading dose followed by 200 mg/day for 56 days. The placebo group received placebo both for the loading dose and for the subsequent 56 doses. At the first planned interim analysis by the Extramural Monitoring Committee, the high-dose Sygen group was dropped (while the investigators remained blinded as to which group was dropped), and an additional stratification was added for age above or below 30 years.

The primary efficacy end point was specified as the proportion of patients with “marked recovery,” defined as a two-grade improvement between baseline AIS grade and 26-week modified Benzel grade. Secondary efficacy assessments included the time course of marked recovery, ASIA motor and sensory scores, relative and absolute sensory levels of impairment, and assessments of bowel and bladder function.

Table 36-1 ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) Used in the Baseline Evaluation

| AIS Grade | Description | Equivalent MBC Grade(s) |

|---|---|---|

| A | No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5 | I |

| B | Sensory but no motor function is preserved below the neurologic level and extends through the sacral segments S4-S5 | II |

| C | Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and the majority of key muscles below the level have a muscle grade less than 3 | III |

| D | Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and the majority of key muscles below the level have a muscle grade greater than or equal to 3 | IV, V, VI |

| E | Motor and sensory function are normal | VII |

MBC: modified Benzel classification.

Table 36-2 Modified Benzel Classification (MBC) with Equivalent ASIA Impairment Scale (AIS) Grade(s)

| MBC Grade | Description | Equivalent AIS Grade(s) |

|---|---|---|

| I | No motor or sensory function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5 | A |

| II | Sensory but no motor function is preserved in the sacral segments S4-S5 | B |

| III | Motor function is preserved below the neurologic level, and the majority of key muscles below the neurologic level have a muscle grade less than 3; unable to walk | C |

| IV | Unable to walk; some functional motor control below the level of injury that is significantly useful (assist in transfers, etc.) but that is not sufficient for independent walking. | (C*), D |

| V | Limited walking; motor function allows walking with assistance or unassisted, but significant problems secondary to lack of endurance or fear of falling limit patient mobility (must be able to ambulate at least 25 feet) | D |

| VI | Unlimited walking; ambulatory without assistance and without significant limitations other than one or both of the following: difficulties with micturition; slightly discoordinated gait (must be able to ambulate at least 150 feet without a helper) | D |

| VII | Neurologically intact with the exception of minimal deficits that cause no functional difficulties (must have a neurologically normal gait and be able to walk without assistance or assistive devices) | (D*), E |

* Only a few patients fit this AIS description

Patients were eligible for this study if they had a major SCI, defined as an injury rostral to the T10 bony level resulting in a neurologic deficit in at least one lower limb that had an ASIA motor score of less than 15 out of a possible 25 points. Patients had to have the potential for recovery from their SCI. Thus, patients with spinal cord transection or penetration were excluded. Patients with significant cauda equina, plexus, or peripheral nerve injury were also excluded. All patients received the NASCIS 2–recommended dose regimen of MPSS within 8 hours of injury. The study medication was initiated within 72 hours of the SCI, but only after completion of the MPSS therapy to avoid possible drug—drug interaction between MPSS and Sygen.

All patients received a baseline evaluation after emergency room assessment and administration of MPSS. The baseline assessment was performed just prior to the first dose of study medication. Thus, the baseline examination to which all subsequent examinations were compared was recorded after the 24-hour MPSS had been administered and after performance of hemodynamic resuscitation, mechanical decompression, and multiple neurologic examinations. Any increase in neurologic function between the emergency room exam and the baseline examination was thus not included in the documentation of change in neurologic function between baseline and follow-up evaluations, which were performed at 4, 8, 16, 26, and 52 weeks.

The pretreatment neurologic assessment utilized both the AIS (Table 36-1) and a detailed ASIA motor and sensory examination. The modified Benzel classification (Table 36-2) and detailed ASIA motor and sensory examinations were performed at 4, 8, 16, 26, and 52 weeks. A follow-up scale different from the baseline measurement scale was used because it included walking ability and also expanded the D classification in the AIS. Because most patients had an unstable spinal fracture at baseline, it was not possible to assess walking ability at that time, thus necessitating the use of different baseline and follow-up scales.

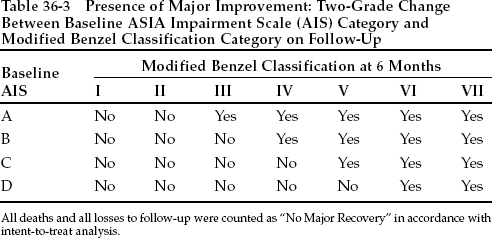

The definitions of Benzel grades I, II, and III are essentially the same as those of AIS grades A, B, and C, respectively. The higher functional grades of the Benzel scale expand the AIS to include degrees of walking and hence provide information on the patient’s level of function. Major improvement (Table 36-3) was defined as an improvement of at least two grades in the Benzel equivalent of the baseline AIS. For example, in a patient with a baseline AIS grade of A, improvement to at least Benzel category III would be needed to qualify as a major improvement. This definition of major recovery allows the use of a single outcome measure for populations of different injury severities at baseline.

249Study Data Description

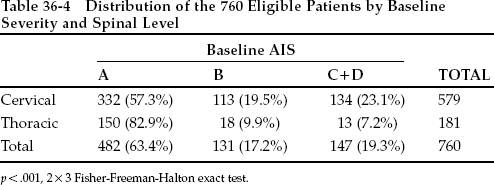

This was the largest prospective SCI drug trial ever conducted: 797 patients randomized during a 5-year recruitment period at 28 neurotrauma centers in North America. Collection of all 12-month follow-up data was completed in February 1998. Overall, 3165 patients were screened, but 2368 were excluded before randomization for failure to satisfy the entry criteria. The most common reason for exclusion was the presence of a spinal fracture with no or minimal neurologic deficits. Of the 797 patients randomized and entered into the study, 37 were later found to be ineligible. Thus, 760 patients are included in the efficacy analysis data.

Data about baseline injury severity and anatomic region of injury in the efficacy analysis data set are shown in Table 36-4. The largest severity group in both the cervical and thoracic region was AIS group A. Fewer patients in all AIS groups were injured in the thoracic than the cervical region. Cervical traction was used in 383 patients, and 604 patients had a spinal operation.

Pearl