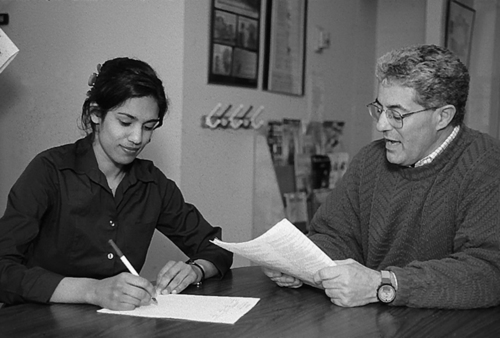

Chapter 13 Readers of this chapter will be able to do the following: 1. Describe typical language development in adolescence. 2. Discuss issues of student-centered assessment at the secondary school level. 3. Discuss screening, case-finding, and eligibility for services for students in secondary schools. 4. Describe the uses of standardized tests, criterion-referenced methods, and observational assessment at the secondary level. 5. Outline methods of assessment of functional communication for adolescent students with severe disabilities and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Crystal is like many children who have language learning disorders (LLD) that stem from a variety of sources. She is one of what Launer (1993) called “the porpoise kids,” whose deficits go below the surface at times and then leap up again at points when the demands of the curriculum increase. These points often occur in fourth and seventh grades, where, in each case, new and taxing changes in the curriculum and in teachers’ expectations of students come into play. Crystal is typical of adolescents with LLD in another way, too. Most don’t appear on the SLP’s doorstep with no history. Almost always, unless they have recently suffered a traumatic injury, they have been assessed and have received services before. That means that they don’t enter our caseloads as clean slates. A great deal of information about their language and learning history is available. The goal of assessment for this period of advanced language development is to use the data available in their files to select assessment questions and focus on the most relevant areas for in-depth appraisal. Adolescents who are functioning at advanced language levels have not only mastered the basic skills of the developing language period but also achieved some of the goals outlined in Chapter 12. They can produce and understand true narratives and some complex sentences, make some inferences, carry on marginally adequate conversations, engage in some metalinguistic discussions, and so on. While these abilities may be present in some aspects of their interactions, though, their skills are, in Nelson’s (1998) words, “wobbly.” Oral language facility can easily be disrupted by stress, when dealing with unfamiliar material or new vocabulary, or when faced with some new communicative goal (such as asking for a date) or cognitive function (such as formulating a scientific hypothesis). Word finding often continues to be a problem. The new skills that normal adolescents are learning during the period of advanced language are primarily concerned with the development of language for more intensive social interactions, with language at the literate end of the oral-literate continuum, and with abilities related to critical thinking (Whitmire, 2000) and executive function (Ciccia, Meulenbroek, & Turkstra, 2009). Vocabulary acquisition involves literate language forms (Nippold, 2007; Westby, 2005) such as the following: • Advanced adverbial conjuncts (similarly, moreover, consequently, in contrast, rather, nonetheless) • Adverbs of likelihood (definitely, possibly) and magnitude (extremely, considerably) • Precise and technical terms related to curricular content (abscissa, bacteria, pollination, fascism) • Verbs with presuppositional (regret), metalinguistic (predict, infer, imply), and metacognitive (hypothesize, observe) components • Words with multiple meanings (strike the ball, strike at the factory; run for office, run the office) • Words with multiple functions (hard stone, hard water, hard feelings) Adolescents acquire more than just a larger vocabulary. They learn to elaborate and expand the meanings of known words (cold meaning temperature; cold meaning affect) and to understand connections among words related in various ways, such as by derivation (clinic, clinician) or by meaning (antonyms [for example, reluctant and enthusiastic]); synonyms [for example, huge and enormous]); or sound (homonyms [for example, pair and pear]) (Nippold, 2007). They also acquire more sophisticated abilities for defining words. Nippold, Hegel, Sohlberg, and Schwarz (1999) showed that, between sixth and twelfth grades, students increased in their ability to provide the most advanced type of definition for abstract nouns, the Aristotelian type. This type of definition contains a superordinate term and a description with one or more characteristics (for example, happiness is a feeling [superordinate term] of pleasure or gladness resulting from a positive experience [description of characteristics]). Sixth-graders produced only one or two of 16 responses at this level, whereas twelfth-graders produced an average of six of 16. Finally, vocabulary development in the secondary years includes increasing understanding of derivational morphology) (Nippold & Sun, 2008), the recognition of root words, prefixes, and suffixes that can change the part of speech and pronunciation of base words (e.g, graph, telegraph, telegraphic). Larsen and Nippold (2007) outline the ways in which morphological development not only supports advanced vocabulary development, but also the expansion of decoding, reading comprehension, and spelling skills. New syntactic skills include growth both within sentences (intrasentential) and between sentences (intersentential). Growth within sentences is seen in small but regular increases in sentence length throughout the school years. Longer sentences are used for particular purposes, though, including narrative, persuasion, and writing. Nippold (2007) reported data showing children used longer sentences in narrative than conversational tasks. Reed, Griffith, and Rasmussen (1998) reported that adolescents used morphosyntactic markers (verb marking, negative forms, etc.) more frequently than did younger children. Nippold, Ward-Lonergan, and Fanning (2005) showed that persuasive contexts elicited the most advanced syntactic forms in adolescents’ writing; Nippold, Mansfield, and Billow (2007) showed that explanation of peer conflicts elicited the longest and most complex sentences in oral discourse. These results indicate that the use of increasing numbers of basic grammatical markers is one means by which sentences become longer during the adolescent years. Intrasentential growth, then, is seen both in the use of newly acquired forms, as well as in increased density of earlier-acquired forms within sentences. Intrasentential growth also is seen in the increasing use of subordinate and coordinate clauses, as well as in the use of low-frequency syntactic structures associated with literate language style. Intersentential growth in the forms used to link sentences also is an important part of adolescent language development. The use of conjunctions and other forms of cohesive devices becomes more frequent and effective during the secondary school years (Nippold, 2007). In addition to these new semantic and syntactic skills, typical adolescents develop a variety of new pragmatic abilities. They begin to use and understand language that has a figurative, rather than literal, function (Nippold, 2007; Nippold & Haq, 1996; Nippold, Moran, & Swartz, 2001; Quals & O’Brien, 2003). They make puns, use sarcasm, and gradually learn to use and comprehend metaphors (“she’s a whirlwind”), similes (“like a diamond in the sky”), proverbs (“a stitch in time saves nine”), and idioms (“raining cats and dogs”). Slang and in-group language become important, and the ability to discern the appropriate uses of this slang helps to determine group membership and peer acceptance (Nippold, 2007). Also, adolescents become significantly more proficient at using communication for purposes such as persuasion, negotiation, and establishing social dominance (Nippold, 1994). Moreover, unlike in earlier childhood when friendship revolved around shared activity, in adolescence, talk itself becomes the major medium of social interaction. It represents a new aspect of the teen’s relation to the social world, where friendship is negotiated primarily by “just talking,” sharing intimacies and experiences for the sake of communication alone (Raffaelli & Duckett, 1989). School also plays a role in the normal adolescent’s language development. New forms of discourse, such as class lectures and expository texts, are introduced in the curriculum, and students need to learn to process and produce them. Secondary school requires students to produce more extended written forms of communication than they did at the elementary grades. Students are required to produce not only stories, but expository and persuasive texts. The understanding of these texts undergoes a predictable sequence of development during the secondary school years (Scott, 2005). These written forms require a great deal of metacognitive and metalinguistic activity. Formal operational thought is the new cognitive development of the adolescent period. It allows teens to move beyond concrete experiences and begin to think abstractly, reason logically, draw conclusions from the information available, and apply all these processes to hypothetical situations. Formal operational thought greatly extends the student’s capacity to think about thinking processes and to entertain hypotheses, coordinate abstractions, and use logical operations. Formal operational thought emerges during this period in normal development (Kamhi & Lee, 1988; Nippold, 1998) and is elaborated throughout the secondary school years. School work builds on formal thought capacities by teaching mathematics and science that make use of and provide practice in exercising these skills. Formal operational thinking also allows teens to develop a variety of verbal-reasoning and critical-thinking skills (Nippold, 2007). Analogical or inductive reasoning (“Apple is to fruit as potato is to vegetable”) develops. Adolescents learn to use syllogisms or deductive reasoning, in problems such as “John is taller than Mary. Mary is taller than Pete. Who is tallest—John, Mary, or Pete?” These formal-operational and verbal-reasoning skills, in normal teens, also allow for a much greater range of metacognitive activities than are typical of elementary-age children. Again, the school curriculum both demands and provides forums for practicing these skills. The kinds of demands that the middle and high school curriculum place on students were discussed by Montgomery and Levine (1995), Schumaker and Deshler (1984), and Whitmire (2000b). These are summarized in Box 13-1. These demands draw on many of the abilities we’ve been discussing that normally evolve during the adolescent years. For adolescents with LLD, as we’ve seen, the oral language and literacy skills developed during the elementary years may still be “wobbly.” These shaky skills can form a weak foundation for the advanced language required by the more intense demands of the secondary curriculum. For these reasons, children who had difficulties acquiring oral language and literacy at the L4L stage continue to have problems with advanced language during the secondary school years. A variety of studies looking at children with histories of language impairments find that these impairments do not disappear in older children and adolescents. Both Conti-Ramsden et al. (2009) and Rescorla (2009) reported on adolescent outcomes of children with histories of language delay. Both report that not all of these individuals require special education throughout their school years, although they do continue to score, on average, lower than peers on tests of language, verbal memory, and verbal reasoning. Still, Durkin et al. (2009) reported that three-quarters of these students received some form of academic support, and that educational attainment was consistently poorer than that of typically developing peers. They and Nippold (2010a) emphasize the importance of evaluating children with a history of language delay as they make the transition from primary to secondary school, in order to provide the levels of support they need to complete their education. Moreover, Wadman, Durkin, and Conti-Ramsden (2008) also report that it is not only academic abilities that are affected. Older student with LLD are at risk for low self-esteem and shyness, despite a desire to make friends and “fit in.” These findings should lead us to conclude that secondary students with LLD will continue to require targeted supports for both academic and social functions. Let’s talk about how we can assess these advanced language skills to identify ways to help our students with LLD manage in the secondary school environment and its social setting. We’ve talked often about the importance of the client’s family in any successful program of assessment and intervention. We still want to keep families involved and informed in an adolescent’s program, using some of the techniques we talked about in Chapters 11 and 12. However, one of the hallmarks of adolescence is the beginning of a movement away from the family of origin as the primary social unit, toward more independence and peer-group orientation. We need to think about this developmental shift in planning assessment for this age group. We can attempt to provide a student-centered program when working with clients at advanced language levels. Let’s see how we might do it. McKinley and Larsen (2003) discussed the importance of student motivation in assessing adolescents. They suggested, first, that the clinician have no “hidden agenda” in the assessment process. Larson and McKinley (1995) advocated telling the student what behaviors (listening, speaking, thinking, writing, etc.) are going to be assessed. Tests and other methods to be used in the assessment can be introduced to the client and the purpose of each explained. Other assessment methods to be used, such as speech, narrative, or writing sampling, also can be previewed, with an explanation of the uses to which the clinician will put each procedure. Teens also need to know why particular behaviors are being assessed. Clinicians can explain, for example, that it is important to know about the student’s listening and understanding of words and sentences in order to figure out how problems with listening might be getting in the way of succeeding in the classroom or interacting successfully with friends. It is important to emphasize to adolescents that the skills we are assessing are important not only for succeeding in school but also for interacting with peers and for developing vocational and independent-living opportunities. The goal of such a student-centered approach to assessment is to establish a cooperative partnership between the teen and the clinician. Only through this partnership can we get the clearest picture of the adolescent’s abilities. And, if we decide intervention is warranted, this partnership stands us in good stead for achieving the full cooperation of the client and eliciting the most highly motivated performance. One method that can be used to assist in this student-centered assessment is to ask the student to do some self-assessment. Grambau (1993) provided one example of such a self-assessment inventory; an adaptation is given in Figure 13-1. This form can be given to the student at the beginning of the evaluation. The student’s self-assessment can be used to guide the process, focusing the clinician’s attention on areas in which students perceive themselves to be having trouble. These areas can be investigated in depth as part of the assessment. Some secondary school programs may use responsiveness to intervention (RTI) models to identify students who struggle with curricular demands (e.g., Vaughn et al., 2008). However, this approach does not yet have strong evidence at the secondary level (Brozo, 2009; Cobb et al., 2005) and is difficult to accomplish in the block-scheduled culture of most secondary schools. While some students may be referred to SLPs and other special educators through the progress monitoring process in RTI programs, most secondary students will find their way onto SLP caseloads in other ways. Larson and McKinley (1995) suggested that mass screening for language disorders in secondary schools is probably not an efficient use of the SLP’s time. Instead, they proposed focusing screening on at-risk populations. These would include adolescents placed in special classrooms, students receiving remedial reading assistance, those in danger of dropping out of school, and those having academic problems that aren’t caused primarily by lack of motivation. Both Blanton and Dagenais (2007) and Sanger et al. (2003) have reported an unusually high prevalence of unidentified language disorders among adolescent delinquents, so it is important to screen students who seem to be having behavioral or social difficulties, even if they have not been previously thought to have communication problems. Such students may have unidentified LLD and could benefit from assessment and intervention with the speech-language pathologist. A sampling of screening tests available for use with students at advanced language levels appears in Appendix 13-1. These screening measures need to be used with some caution, though. Nelson (1998) pointed out that many screening tests developed for adolescents may not be sensitive to the problems that can occur at advanced language levels and have an impact on school and personal adjustment. If an at-risk student passes one of these screenings but the clinician has a “hunch” that the passing score is not a good reflection of the student’s functional language ability, a talk with some of the student’s teachers may be warranted. If the teachers confirm the clinician’s hunch that language disabilities are getting in the student’s way, some standardized testing in greater depth may be warranted to determine whether the student would be eligible for services on the basis of scores from more extensive testing. Other sources of referral are most likely to be the teachers and counselors who work with students in the school. For these referral sources, it is especially important to provide practical criteria for making referral. Using a pragmatically oriented checklist, like the one in Figure 11-1, can be helpful for eliciting referrals from these sources. So can a referral checklist that focuses on skills that are required by the secondary curriculum. Figure 13-2 gives an example of a checklist that incorporates the pragmatic aspects of Figure 11-1 and adds some of the curricular demands of Box 13-1. A checklist like this can be given to teachers at in-service programs that discuss adolescent language and the needs of students with LLD at this level. Alternatively, it can be distributed to teachers with a short cover note explaining the clinician’s interest in helping students to acquire language skills that will increase success in the classroom. Teachers can be asked to fill out the form for any student whom they suspect may have “wobbly” language abilities. If teachers are unwilling to fill out the forms, the SLP might arrange a short meeting with the teacher and ask the teacher to think of any students who might be having trouble. The clinician can simply ask the questions on the form and record the answers for each student about whom the teacher has concerns. Students who show significant problems on an inventory like the one in Figure 13-2 can be assessed for eligibility using standardized test batteries. A screening test would not be necessary, since the screening was done by the teacher by filling out the checklist. When choosing and interpreting standardized tests at advanced language levels, we need to bear in mind all the warnings we have discussed all along for standardized tests. Several are particularly germane in the advanced language period. The need to identify pragmatic as well as semantic and syntactic areas of need is especially important, since pragmatics may be the area of greatest deficit in adolescents with LLD. And of course, we will need to attend to the ways in which the student’s oral language skills support reading and writing in the curriculum. Like screening tests, standardized tests at advanced language levels may not be sufficiently sensitive to higher level language skills to identify deficits in students with minimally adequate basic oral language abilities who are still having trouble with secondary school work. They also may fail to sample the extended discourse contexts that are necessary for success in school, like narratives and expository prose. Nelson (1998) suggested that the most appropriate uses of standardized tests of advanced language include identifying the dimensions of the language disorder—dimensions such as oral language, written expression, and comprehension of language forms in listening and reading. We can, then, select standardized tests for adolescents using a strategy similar to the one discussed for elementary students in Chapter 12. That is, we can use standardized tests that sample a broad spectrum of oral and written receptive and expressive abilities. If necessary, the assessment for eligibility can be supplemented with tests of pragmatics and tests of learning-related skills to establish eligibility, as we discussed in Chapter 11. At the advanced language level, some tests particularly helpful in this regard include the following: • Test of Word Knowledge (Wiig & Secord, 1992a): assesses aspects of lexical skill including definitions, synonyms, antonyms, metalinguistics, and figurative language. • Test of Language Competence—Expanded (Wiig & Secord, 1989): provides assessment of structural ambiguities, figurative language, and ability to draw inferences. • Test of Adolescent and Adult Language—4 (Hammill, Brown, Larsen, & Wiederholt, 2007): provides broad assessment of syntactic forms in the Listening Grammar, Speaking Grammar, Reading Grammar, and Writing Grammar subtests. • Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003): the Formulating Sentences, Recalling Sentences, and Sentence Assembly subtests tap various aspects of grammatical production. • Test of Language Development-Intermediate—4 (Hammill & Newcomer, 2008): the Sentence Combining and Word Ordering subtests have shown good correlations with production in spontaneous discourse (Scott & Stokes, 1995). • Test of Written Language—4 (Hammill & Larsen, 2009): measures structural elements in writing in students to age 17. • Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999b): measures semantic, syntactic, pragmatic, and supralinguistic aspects of language. • Oral and Written Language Scales (OWLS; Carrow-Woolfolk, 1996): Measures written expression, oral expression, and listening comprehension for children ages 5 through 21. Appendix 13-2 provides a list of standardized tests that are appropriate for students at advanced language levels. Activity with the SLP must result in academic credit toward graduation (Larson, McKinley, & Boley, 1993). Students will not be willing to devote time voluntarily to activities for which they receive no credit. Larson and McKinley (2003b) also suggested taking care in naming programs, so that they sound like academic courses rather than therapy. Communication Studies, Effective Communication, and Communication Laboratory are some examples of likely titles. Of course, students who refer themselves must qualify for services, just as students referred from other sources do. Using a self-assessment checklist like the one in Figure 13-2 can be an effective screening measure for adolescent self-referrals. If the student checks only a few of the areas on the form, the student’s problem may not qualify him or her for intervention services. The clinician might talk briefly with such students to give them focused tips on study skills or peer communication or in whatever area they were feeling inadequate. Alternatively, the SLP might refer these students to the school counselor. Students at an L4L level will probably make a few grammatical errors in speech and will display writing samples that are brief; contain short, simple sentences; show difficulty with the mechanics of spelling, capitalization, and punctuation; have little or no organization or macrostructure; and show sparse expression of ideas. In other words, their writing will be like that of a second- or third-grader rather than a secondary student. Students functioning at advanced language stages may display word-finding problems, limited vocabulary, and pragmatic errors in conversation, but will have mastered basic oral language rules. Their writing will be less mature and sophisticated than that of their peers but will display some competence with mechanics, some limited use of complex sentences, and some degree of organization and semantic content (Dockrell, Lindsay, & Connelly, 2009; Scott, 1999). For students appearing to function at L4L stages in the secondary school years, assessment can focus on areas outlined in Chapter 11 along with some assessment of functional skills needed to survive in the academic and vocational environments that students must face. For students who have basic oral and written language skills, assessment of areas of advanced language development can proceed. Let’s look at some of the areas that can be a part of this assessment. Nippold (2007) discussed the importance of the development in adolescence of a “literate lexicon,” the words needed to understand and produce language near the literate end of the oral-literate continuum. Table 13-1 provides some examples of the kinds of words and morphemes secondary students typically encounter in the academic curriculum. Many of these words will be new to our clients, and will have to be learned in order to participate in this curriculum. Nipold (2007) highlights three main avenues of vocabulary learning for older students: Table 13-1 Examples of Words and Morphemes Typically Encountered in the Secondary Curriculum Adapted from Nippold, M. (2007). Later language development: School-age, children, adolescents, and young adults (3rd edition), (pp. 50-55). Austin, TX: Pro-Ed. Contextual abstraction (Sternberg, 1987) is the ability to infer the meaning of a new word from the linguistic cues that accompany it. We can assess students’ ability to do this by having them read (or listen to the clinician read) a passage that has some difficult, unfamiliar words. We can ask students to guess what the difficult words mean and to tell why they think so. Students who have trouble using context to infer meaning in these activities can be given practice in doing so as part of the intervention program. Nippold (2007) identified several categories of words particularly important for the literate lexicon. These include nouns for technical and curriculum activities (salutation, oppression, circumference, proton). Words like these can be identified and assessed using curriculum-based methods such as those discussed in Chapter 11. Artifact analysis is a particularly useful format here. Students’ written work can be analyzed to see which curricular vocabulary items are misused or avoided. These words can be focused on in the intervention program. Another class of words in the literate lexicon is verbs used in discussions of spoken and written language interpretation and for talking about cognitive and logical processes (Nippold, 2007). They include verbs that refer to both metacognitive (remember, doubt, infer, hypothesize, conclude, assume) and metalinguistic (assert, concede, imply, predict, report, interpret, confirm) activities. Verbs with presuppositional aspects in their meaning also would be included in the category. Two types of verbs have presuppositional components: factives and nonfactives. Factive verbs presuppose or assume the truth of the following clause (“We regret that your application is denied.”). They include examples such as know, notice, forget, and regret. With nonfactive verbs, the truth of the following proposition is uncertain (“I suppose my application was denied.”) They include verbs such as think, believe, figure, say, suppose, and guess. Nippold (1998) reported that these verbs continue to develop and expand in meaning in the vocabularies of normally developing adolescents. There is good reason to believe, then, that they can cause difficulties for students with LLD. Assessment of vocabulary with standardized tests can be supplemented with informal assessment of verbs like these, since they are likely to cause problems and are necessary to establish competency with literate language. Here a metalinguistic approach to assessment can be used. The clinician can simply present a list of curriculum-related words gathered from classroom teachers and ask clients to tell what they know about them. A “Knowledge Rating Checklist” like the one in Table 12-1 can be helpful. Students can fill out the chart for each word on the clinician’s list, and the clinician can work with students on words whose meanings are shaky for them. Scott (2010) suggests using qualitative analysis of literate vocabulary. She reports that asking college students to identify “high level” words in the writing of secondary students resulted in high levels of agreement, even with only minimal instruction as to what constituted a “high level” word (i.e., find words that are more adult-like and less frequent). You might like to try your hand at identifying the “high level” words in the passage in Box 13-2 (our answers appear in Appendix 13-3). Another qualitative metric for assessment of literate vocabulary is simply word length. Scott suggests using word processing software that calculates the average number of characters/word as one index. Similar software can also be used to identify words that are not among the most common 1000 words in an on-line word frequency list (e.g., Word Frequency Text Profiles [Edict, 2008]). These counts can be used both to compare values between a client’s writing sample (or speech sample transcribed by the clinician), and a similar sample from several peers. They can also be used to track change in vocabulary over the course of an intervention program. Research suggests that 25% to 50% of children with LLD have problems with word finding (Messer and Dockrell, 2006). When we talked about word-finding difficulties for children in the L4L stage, we discussed the fact that a large discrepancy between scores on a receptive vocabulary test and an expressive vocabulary test is one signal of this problem. At the advanced language level, tests such as the Receptive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—2000 Edition (Brownell, 2000) and the Expressive One-Word Picture Vocabulary Test—2000 Edition (Brownell, 2000), as well as the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test—IV (Dunn & Dunn, 2006) and the Expressive Vocabulary Test—2 (Williams, 2006), might be used for this purpose. Tests specifically designed to assess word retrieval include the Rapid Automatized Naming Task (Wolf & Denckla, 2005) and the Test of Adolescent/Adult Word Finding (German, 1990). Teacher report of word-finding problems or referral checklists would be another. A clinician-made form, like those we’ve discussed, or a commercially available one, like German and German’s (1993) Word-Finding Referral Checklist can be used. German and Newman (2007) suggest further that oral reading assessments that include unusual or unfamiliar words be used, followed with recognition responses (e.g., multiple choice) for words missed in the oral reading, since children with word finding difficulties can often recognize words that they have difficulty retrieving on their own. We also might hear some word-finding problems in the short conversational interaction with which we began the assessment session. In fact, Tingley, Kyte, Johnson, and Beitchman (2003) suggest that it is always important to supplement single-word testing with a conversational sample in assessing word finding, since their research suggests only weak relationships between single-word tests and disruptions in conversational speech. We use the standard expressive and receptive vocabulary tests just discussed to give a general picture of vocabulary development. Crais (1990), however, emphasized the limitations of these tests in that they give a “yes or no” answer as to whether a particular word is “known,” when in reality there are many levels of “knowing” involved in lexical acquisition. Having a partial representation of the meaning of a word is not adequate, for example, to produce a complete definition of the word. Using word definition tasks to assess advanced language stages is appropriate, since the ability to define words is generally acquired by the time normally developing children reach this stage (Nippold, 2007). Several tests of adolescent language have definition subtests that can be used as criterion-referenced assessments. These include The Comprehensive Receptive and Expressive Vocabulary Test—2nd Edition (Wallace & Hammill, 2002), The Test of Word Knowledge (Wiig & Secord, 1992a), and The Word Test 2—Adolescent (Huisingh et al., 2005). We also can simply ask students to give definitions for words derived from textbook or literature selections that they are studying in class. We can assess these informally elicited definitions using the following scoring rubric suggested by Nippold, Hegel, Sohlberg, and Schwarz (1999) and Pease, Gleason, and Pan (1993): • 2 points: contains an accurate superordinate term and describes the word with one or more accurate characteristics (X is a Y that Z; a robin is a bird that has a red breast) • 1 point: contains an accurate superordinate term but does not describe the word accurately (X is a Y; “happiness is a feeling”); describes the word with one or more accurate characteristics, but does not contain an accurate superordinate term (X is when Y; “happiness is when you’re glad”) • 0 points: attempts a response, but it does not contain an accurate superordinate term or accurate description/characteristic; no response Nippold and Haq’s (1996) results suggest that students in sixth grade should receive at least one point for more than half the words presented; those in ninth grade should receive at least one point for more than 75% of the words presented, and those in twelfth grade should receive 2 points for more than half the words presented. Again, subtests of standardized instruments are available to use as criterion-referenced assessment for looking at these kinds of skills. The Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003) has sections testing semantic relationships, as does the Detroit Test of Learning Aptitude—4 (Hammill, 1998), the Test of Language Competence—Expanded Edition (Wiig & Secord, 1989), the Test of Language Development—Intermediate—III (Hammill & Newcomer, 2008), the Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery—Revised (Woodcock, 1991), and The Word Test 2—Adolescent (Huisingh et al., 2005). Other curriculum-based forms of assessment also can be used. These would include reading a passage with a student, from a classroom literature selection, for example. The clinician could ask the student to substitute a synonym for several of the words, ask for antonyms for words, have the student compare and contrast the meanings of related pairs of words in the passage, and ask the student to generate other meanings for a word in the passage that could have more than one. For example, the clinician might present the following passage from The Call of the Wild (London, 1963, pp. 3-4): As we’ve discussed, the ability to use language in nonliteral ways is one of the important developments of the advanced language period. Both Cain and Towse (2008) and Rinaldi (2000) showed that children with LLD had difficulty inferring the meaning of unfamiliar figurative language forms in both oral and written contexts. A few adolescent test batteries have figurative-language processing subtests. The Test of Language Competence—Expanded (Wiig & Secord, 1989) and the Comprehensive Assessment of Spoken Language (Carrow-Woolfolk, 1999) are two examples. We also can use curriculum-based assessment to document deficits in this area. Literature selections from the student’s English class can be analyzed by the clinician for similes, metaphors, idioms, and proverbs. These figures can be presented in context to the student, who is asked to provide an interpretation. We can look at our The Call of the Wild (London, 1963, pp. 4–6) example again: A clinician could ask the student to decide whether the sun really kissed the valley and whether Buck were really a king. The student could be asked to explain what these metaphors did mean and why the author might use them. A similar procedure could be used for the simile egotistical as a country gentleman. Again, these metalinguistic activities require more than basic comprehension of the figurative language forms. But these activities are the kind that will be demanded by the curriculum in which students must function. If assessment of figurative language in contexts like these indicates weakness on the part of the student, intervention that encourages work with figurative forms at a variety of levels can be instituted. In general, figures that refer to concrete objects (“The early bird catches the worm”) are easier than those with abstract words only (“Two wrongs don’t make a right”). Familiar sayings (“Too many cooks spoil the broth”) are easier than unfamiliar ones (“Two captains will sink a ship”). However, Nippold and Taylor (2002) showed that there is a developmental progression in the understanding of idioms from childhood to adolescence so that the familiarity of the idiom becomes less important in determining its difficulty for older students, as they gain greater skill in using context to determine meaning. Qualls and O’Brien (2003) showed that context generally facilitates idiom comprehension (although less for students with LLD than for typical students), so that presenting idioms within a story setting may help students in determining their meaning. We can give students practice hearing, reading, interpreting, talking about, and creating figurative forms in a variety of contexts to increase both comprehension and metalinguistic awareness of these modes of expression. Qualls and O’Brien (2003) selected a list of 24 idioms that represented a range of familiarity to speakers of English. These are presented in Table 13-2. Students who have difficulty inferring and explaining the meaning of common figures in tasks such as these can benefit from exposure to and metalinguistic discussion about idioms in the intervention program that employs contexts in which the students are encouraged to infer the idiom’s meaning. TABLE 13-2 Common Idioms in English, at Three Levels of Familiarity Adapted from Nippold, M., Taylor, C., & Baker, J. (1996). Idiom understanding in Australian youth. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 39, 442-447; Qualls, C., & O’Brien, R. (2003). Contextual variation, familiarity, academic literacy and rural adolescents’ idiom knowledge. Language, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 34, 69-79. We talked at length in Chapter 11 about assessing semantic integration in the L4L period. Many of the same procedures, using grade-appropriate material, can be used in the advanced language stage as well. The Inference subtest of the California Test of Mental Maturity (Sullivan, Clark, & Tiegs, 1961) and of the Test of Language Competence—Expanded Edition (Wiig & Secord, 1989) also can be used as a criterion-referenced procedure to assess this area. Kamhi and Johnston (1992) devised the Propositional Complexity Analysis, which looks at the semantic content in spontaneous speech samples. This procedure can provide an additional means of assessing how the client combines ideas in discourse. The language of thinking—used to solve problems, to plan, organize, predict, speculate, and hypothesize—becomes a major function of communication in the advanced language stage. The ability to use language to extend thinking, reflect on thinking, and entertain several cognitive viewpoints at once are hallmarks of formal operational thought. Students who cannot engage in this kind of language use will be at a distinct disadvantage in many areas of the curriculum, including science, mathematics, and in social studies topics such as history and geography. Several standardized tests assess verbal reasoning. These include the Cornell Reasoning Tests (Ennis et al., 1965), and the Matrix Analogies Tests (Naglieri, 1985). Subtests of some comprehensive batteries also can provide helpful criterion-referenced information on a student’s facility with verbal reasoning. The Woodcock Language Proficiency Battery—Revised (Woodcock, 1991), the Illinois Test of Psycholinguistic Abilities—3rd Edition (Hammill, Mather, & Roberts, 2001), Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children—4th Edition (Wechsler, 2005), Differential Aptitude Test-—5th Edition (Bennett, Seashore, & Wesman, 1990), and the Test of Problem Solving–2 (Dawes et al., 2007) have verbal reasoning sections. Students who have significant difficulties in these areas are helped by working on analogies, syllogisms, and using language to talk through logical problems in the intervention program. Nippold, Ward-Lonergan, and Fanning (2005) also suggest using persuasive writing contexts to scaffold students’ verbal reasoning abilities. Students at advanced language stages should be able to comprehend virtually all the sentence types in the language and should no longer use comprehension strategies for processing difficult sentences. Several language batteries for adolescents have receptive syntax subtests that can be used as criterion-referenced assessments. Some examples include the Clinical Evaluation of Language Fundamentals—4 (Semel, Wiig, & Secord, 2003), the Test of Adolescent and Adult Language—4 (Hammill, Brown, Larsen, & Wiederholt, 2007), and the Test of Language Development—Intermediate—3 (Hammill & Newcomer, 1997). If deficits are identified on receptive syntactic testing or if comprehension strategy use is seen to persist on these measures, intervention should include an input component, as we’ve discussed for earlier stages of development. Activities aimed at eliciting production of advanced language forms should be supplemented with literature-based and curriculum-based script activities. These activities should provide intensive exposure in context to the forms for which comprehension is “wobbly,” and metalinguistic discussion about their meaning to build the comprehension base for these structures. You probably are familiar by now with the arguments about using a language sample to assess syntactic production. Sampling how a student uses language to communicate in real interactive situations provides the most ecologically valid assessment of productive syntax. But what kind of sample should we elicit from a student in the advanced language stage? The use of forms toward the literate end of the oral-literate continuum is the major area we are interested in assessing at this age range. Hadley (1998) suggested that contextual factors are especially important for selecting a sampling situation at this stage. Many interactive situations, such as peer conversations or even informal discourse with adults, do not elicit the advanced forms we are interested in sampling. So we want to select a context that gives us a good chance of observing some of these advanced language forms. This suggests that communication tasks near the literate end of the continuum may be a better source of information on these variables than conversation. Many researchers looking at the syntax of advanced language have used narrative tasks (Blake, Quartaro, & Onorati, 1993; Hadley, 1998; Klecan-Aker & Hedrick, 1985; Morris & Crump, 1982; Nippold, 1998; O’Donnell, Griffin, & Norris, 1967; Scott & Stokes, 1995; Scott & Windsor, 2000; Ukrainetz & Gillam, 2009; Wetherell, Botting, & Conti-Ramsden, 2007). These sampling contexts have several advantages. First, much of the data on syntactic production in adolescents is based on these kinds of tasks. Using them in assessment, then, makes the client’s sample more directly comparable to those in the literature. Second, narrative samples also can be analyzed for other aspects of advanced language, such as cohesion, use of literate lexical items, and narrative stage. Finally, narratives from students at this developmental level have been shown to contain more complex language forms than conversation does (Hadley, 1998). Narratives are, then, more likely to provide examples of the literate language that we hope to elicit. For these reasons, narratives provide one important context for speech sampling with adolescents. A second important sampling context for adolescent oral language is exposition, or explanation. Nippold, Mansfield, Billow, & Tomblin (2008) showed that expository, but not conversational, samples, differentiated adolescents with LLD from those with typical development, and T-unit length and complexity were greater in expository texts than in conversation for both groups. Both narrative and expository samples can be helpful for getting a picture of the most complex syntax a student has available. As we discussed when we talked about assessing narrative in younger children, there are several ways to elicit these samples. Weiss, Temperly, Stierwalt, and Robin (1993) suggested using cartoon strips from the newspaper, with the words “whited-out,” to elicit narrative samples. Ukrainetz et al. (2009) used a short picture sequence of a common event, such as having trouble getting to school on time. Wordless picture books, such as A Boy, a Dog, and a Frog (Mayer, 1967), or films, filmstrips, or videos based on them (for example, Frog, Where Are You? [Osbourne & Templeton, 1994]) can also be used, by asking the student to first look through the pictures and then to tell the story as if reading to a child for whom he or she is baby-sitting. Hadley (1998) suggested a two-step procedure. Students are first asked to retell an episode from a story after looking at pictures or a film of it. They then are asked to generate an ending for the story. This procedure provides an opportunity for clinicians to see whether students do better (as we would expect) when some visual support is provided, and how a student is able to organize and generate a story episode independently.

Assessing advanced language

Language development in adolescence

Adolescents with LLD

Student-centered assessment

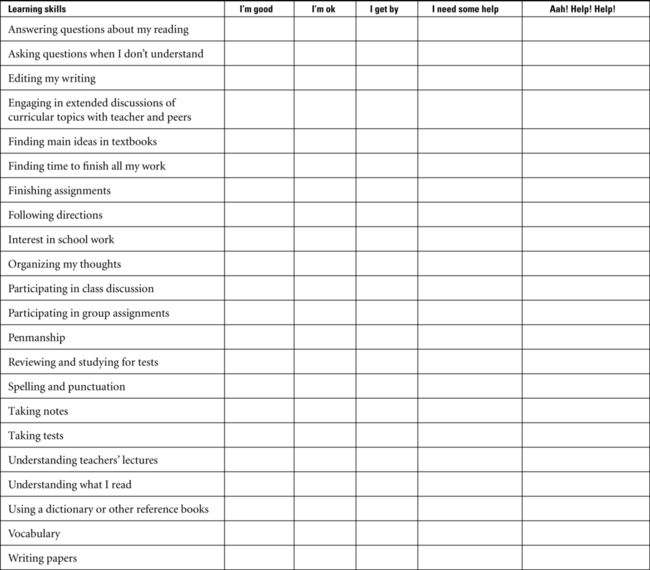

Screening, case finding, and establishing eligibility with standardized tests in the advanced language stage

Criterion-referenced assessment and behavioral observation in the advanced language stage

Semantics

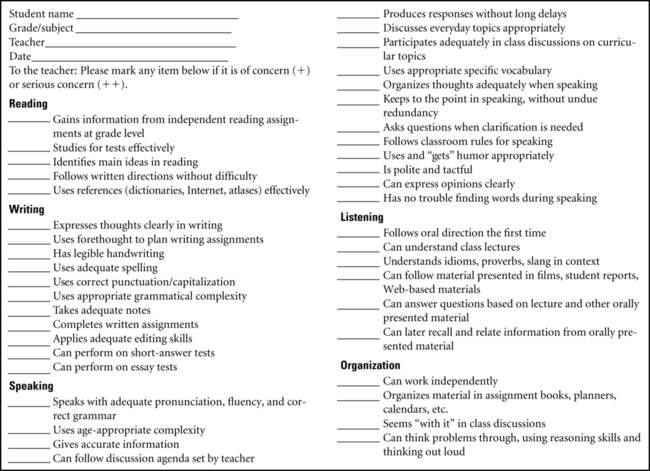

The literate lexicon

Example Words

Morphemes

Prefixes:

Anti-

anticlimax, antifreeze, antiaging

Co-

coauthor, coexist, copilot

Dis-

disability, dishonest, distrust

Mal-

maladaptive, malpractice, malnourished

Mis-

misfire, mislead, mismatch

Multi-

multicultural, multimedia, multisensory

Non-

nonfat, nonverbal, nonprofit

Pre-

precautions, pre-existing, prefabricate

Re-

rebuild, recall, refinance

Sub-

subgroup, submarine, substandard

Un-

unable, unavailable, uneasy

Noun Suffixes:

-cide

genocide, germicide, homicide

-ism

criticism, symbolism, journalism

-ist

activist, colonist, pathologist

-ology

biology, geology, herbology

Verb Suffixes:

-ate

activate, evaluate, gravitate

-ize

colonize, fertilize, naturalize

Adjective Suffixes:

-able

enjoyable, manageable, testable

-ese

Japanese, legalese, motherese

-ful

artful, painful, pitiful

-less

ageless, flawless, matchless

-some

bothersome, wearisome, wholesome

Adverb Suffixes:

-fully

gratefully, peacefully, skillfully

-ly

angrily, quietly, sadly

Curricular Areas

Math

additive, algebraic, associative, commutative, factorization, tesselation

Science

alkaline, bimetallic, crystalline, echolocation, endothermic, ferromagnetic, molecular, unsaturated

Social Studies

circumnavigate, domesticate, federalism, imperialism, mercantilism, nationalism, pilgrimage, subcontinent

Word retrieval

Word definitions

Word relations

Figurative language

Low Familiarity

Moderate Familiarity

High Familiarity

Take down a peg

Go into one’s shell

Let off some steam

Vote with one’s feet

Strike the right note

Go around in circles

Paper over the cracks

Keep up one’s end

Put one’s foot down

Hoe ones’s own row

Cross swords with someone

Breathe down someone’s neck

Talk through one’s hat

Blow away the cobwebs

Put their heads together

Lead with one’s chin

Make one’s hair curl

Skate on thin ice

Rise to the bait

Throw to the wolves

Beat around the bush

Have a hollow ring

Go against the grain

Read between the lines

Semantic integration

Verbal reasoning

Syntax and morphology

Comprehension

Production

Sampling contexts for literate language

Eliciting narrative samples

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Crystal had two younger brothers who were both diagnosed with fragile X syndrome when she was in third grade. At that time, Crystal was tested, too, and found to be positive for the syndrome. Before that, she’d been thought of by her teachers as something of a “slow learner,” who had barely managed to stay at grade level. Once the diagnosis was established, she received a thorough assessment. She was found not to be eligible for services in third grade, since she was functioning within normal limits, although near the borderline. She was put on monitoring status and reevaluated 1 year later. By that time, her scores on a battery of oral language and reading tests had slipped below the cut-off and qualified her for services in language and reading. She received intervention throughout fourth and fifth grades and was able to function in regular classes. By the end of fifth grade she was making satisfactory progress, had age-appropriate oral language skills in most areas, and was reading on a fourth-grade level. It was decided to send her on to middle school with her class, to furlough her from direct intervention, and to monitor her progress.

Crystal had two younger brothers who were both diagnosed with fragile X syndrome when she was in third grade. At that time, Crystal was tested, too, and found to be positive for the syndrome. Before that, she’d been thought of by her teachers as something of a “slow learner,” who had barely managed to stay at grade level. Once the diagnosis was established, she received a thorough assessment. She was found not to be eligible for services in third grade, since she was functioning within normal limits, although near the borderline. She was put on monitoring status and reevaluated 1 year later. By that time, her scores on a battery of oral language and reading tests had slipped below the cut-off and qualified her for services in language and reading. She received intervention throughout fourth and fifth grades and was able to function in regular classes. By the end of fifth grade she was making satisfactory progress, had age-appropriate oral language skills in most areas, and was reading on a fourth-grade level. It was decided to send her on to middle school with her class, to furlough her from direct intervention, and to monitor her progress.