OBJECTIVES

Objectives

Define medication adherence.

Describe the scope and consequences of poor medication adherence.

Summarize the patient, clinician, and system factors that contribute to poor medication adherence.

Describe clinician–patient communication strategies to assess and promote medication adherence.

Identify interventions to promote medication adherence.

INTRODUCTION

Mr. Cruise is a 55-year-old janitor who left his job 1 year ago because of worsening heart failure, hypertension, and diabetes. He manages to keep his regular appointments with his cardiologist and primary care physician, but over the past year, he has been hospitalized four times for management of his heart failure. During each hospitalization, his medical team suspects poor adherence with his medication regimen.

Patients living with chronic disease (e.g., hypertension, diabetes, or HIV) often have complex treatment regimens and use multiple medications. Patients may find that being adherent with medications is a challenge, and poor medication adherence makes it difficult to achieve the desired goals of chronic disease management.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines adherence as “the extent to which a person’s behavior—taking medications, following a diet, and/or executing lifestyle changes—corresponds to agreed recommendations from a health care provider.”1 Many factors influence an individual’s ability to adhere to medication instructions and agreed upon life-style behavioral changes required to manage chronic disease. Medication adherence is an essential element to achieving positive therapy outcomes. Therefore, strategies focused on improving adherence should also strengthen the collaboration between patients, family members, caregivers, and clinicians and mitigate patient, clinician, and system barriers to adherence.

This chapter describes the problem of poor medication adherence, and explores patient, clinician, and system factors that contribute to poor adherence. It provides communication strategies designed to identify factors that result in poor adherence, clarify the causes of poor adherence, and promote higher levels of adherence.

SCOPE OF THE PROBLEM

Mr. Cruise’s clinical picture is complex and his responses to his medication regimen are unexpectedly poor. He has had frequent hospitalizations for his chronic illnesses, and few of his medications seem to be working as predicted.

Poor medication adherence is a worldwide problem and the problem is growing as the burden of chronic disease is growing.1 Studies suggest that as many as half of medical patients do not completely follow the treatment recommendations of their clinicians in developed countries such as the United States; the rates are often much lower in developing countries in Africa and Asia.1,2 Poor adherence is of particular concern among those with multiple chronic medical problems, such as HIV, hypertension, and diabetes,3,4 as well as among lower-income patients who face many barriers to adherence, including access to medications and rising medication costs.5 In resource-poor countries such as Africa, patients on antiretroviral therapy experience barriers to adherence that include food insecurity and transportation costs.6

The consequences of poor adherence can be devastating. Over 100,000 deaths annually in the United States have been attributed to poor adherence with medication regimens.7 Poor medication adherence also leads to higher rates of hospitalizations, emergency room visits, and outpatient visits, as well as worsening health status.2,8 In addition to adverse health consequences and potential financial waste, poor adherence can lead to frustration for both patients and clinicians and thus may contribute to the breakdown in this relationship and mistrust of the health-care system.

FACTORS ASSOCIATED WITH POOR ADHERENCE

Mr. Cruise takes nine different medications: six for management of his heart disease and three for his diabetes. Since leaving his job, he has experienced severe financial strain and now suffers from depression.

Patients may experience many factors that can have an impact on their ability to properly take medications. These factors include, but are not limited to access, low resources, lack of social support, mental illness, health beliefs, substance abuse, mistrust of the health-care system, negative personal interactions with clinicians, fear, and lack of understanding of disease and medications. Patients may believe that they are adherent to medications because they take a medication every day, when in fact how the patient takes the medication may be incorrect. It is important when assessing medication adherence that providers ask the patients, “tell me how you take this medication.” There are multiple reasons that patients choose not to follow the advice of their health-care providers, particularly when complex medication regimens or side effects conflict with the patient’s personal identity or goals.9 Understanding the elements at the interface of patient and treatment may contribute to better assessment and management of poor adherence.

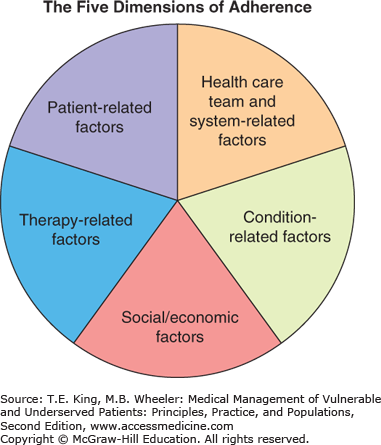

The WHO describes five dimensions that affect adherence: (1) therapy related, (2) patient related, (3) social and economic factors, (4) condition related, and (5) health-care system related.1 These factors are often intertwined to varying degrees and influence a patient’s ability to adhere to medications (Figure 13-1). These dimensions are to be considered as we assess medication adherence and choose strategies to improve adherence.

Figure 13-1.

The five dimensions of adherence. Optimal treatment frequently requires addressing several barriers to adherence. Health professionals must follow a systematic process to assess all the potential barriers. (Adapted from Sabaté E. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies. Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2003:27.)

All medications have potential side effects, and the number of side effects increases with the complexity of the regimen. Although clinicians may be vigilant for serious side effects, they may be less conscious of those that are not life threatening, but significantly interfere with a patient’s functioning. Moreover, the patient may perceive the desired effect of the medication as an adverse side effect. For example, patients may take diuretic medications at night, leading to disrupted sleep due to frequent need to urinate. Instead, taking diuretics in the morning may relieve this problem. However, such changes in the dosing schedule may prove challenging for individuals who do not have ready access to bathroom facilities when they are away from their homes.

The seriousness of side effects is often idiosyncratic, and must be assessed for patients individually, as there will be different levels of tolerance for medication side effects. For example, although the cough associated with the use of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors is inconsequential for many patients, it may prompt avoidance in others. Patients may be reluctant to discuss certain side effects with their clinicians (e.g., loss of libido associated with some medications). Patients may not know what steps to take if they miss a dose of medication. They may not know when to take the dose of medication as soon as they remember, or to wait until the next regular dosing time. Medications used to treat depression require several weeks before any effect is seen and due to early side effects, patients may stop the medications because the side effects make them feel ill, and their depression is not yet getting any better. In addition to the actual effects and side effects of medications, unrelated new or recurrent symptoms may be attributed to a new medication by some patients and thus may contribute to poor adherence.

The average older patient with two or more chronic illnesses is treated with more than six daily medications. Although many of these may be taken once daily, others may require multiple daily doses. Patients may experience scheduling conflicts associated with their medication regimens, particularly when their medication schedules change frequently, such as with warfarin, insulin, and diuretics. Some medications must be taken with food and others require an empty stomach. Patients with issues of food insecurity may not be able to adhere to the instructions of taking medications with food. This complexity is further compounded by the fact that certain medications must not be taken at the same time as others. Many work environments do not permit scheduled breaks to take medications or monitor effects of medications (e.g., blood sugar check for diabetes). Patients living in low-income housing units or who are homeless may not have access to proper storage facilities for their medications (e.g., refrigeration).

Even if a patient chooses to follow recommendations, misunderstanding, uncertainty, and confusion about the actual recommendation can lead to poor adherence. Patients may recall and comprehend as little as 50% of what is conveyed to them in a medical visit,10,11,12,13 and often do not have a clear understanding of the doses and indications for each of their medications. Additionally, patients may not appreciate that treatment of chronic conditions such as hypertension and diabetes require the ongoing use of medications, and consequently may fail to obtain refills once their prescription is completed.

Administration of medications to children is challenging because most medications come in liquid form. For example, a dose of medication may be ordered in milligrams; however, the parents and caregivers may need to be taught to convert the dose to milliliters or teaspoons for administration. The mathematical conversions often times can result in errors and confusion, leading to the administration of the incorrect dose of the medication. Care must be taken to ensure that parents and caregivers have clearly marked measuring tools and understand the conversions of doses. This also applies to adult patients who may require medications in liquid form.

Patients with cognitive impairments that result from aging or complications of underlying diseases (e.g., cerebrovascular disease) may be at particular risk for confusion with their medication regimens.14 Patients require labeling instructions that they can understand. Large print may be required to accommodate those patients with visual impairment.

Limited literacy is a worldwide problem and it is important that care be delivered at the level needed for patients. Language barriers and low functional health literacy15 have been recognized as important contributors to confusion with medication regimens. Health literacy refers to patients’ ability to “obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services they need to make appropriate health decisions.”16 Patients who may be particularly vulnerable to low functional health literacy include older patients, those with lower levels of education and literacy, and those with limited English proficiency. As many as 50% of patients cared for at public hospitals and safety-net settings may have low functional health literacy.17 The written word may not be sufficient for patients to get a clear understanding of medication administration instructions and providers will need to use pictures and drawings to promote medication adherence (see Chapter 15).18

Patients’ beliefs about health, health care, or their particular medical conditions may differ substantially from those of their health-care providers. These beliefs may range from use of complementary and alternative medicines to religious beliefs and the conviction that there is no need to take medications if one is asymptomatic (often encountered in the treatment of hypertension).19 Such health beliefs on the part of patients do not invariably lead to poor adherence if the beliefs are acknowledged and integrated into the patient’s overall treatment plan. Clinicians who engage patients in nonjudgmental discussions of their use of complementary and alternative medicines, for example, may be better able to establish the rapport necessary to enable improved adherence, as well as identify potential serious interactions among treatments.

Social support plays an important role in overall health and well-being, and appears to be instrumental in ensuring medication adherence.20 Social support encompasses emotional (love, affirmation) as well as practical support (food, shelter, money, transportation). Patients who have a social network and environment that supports and promotes the behaviors that contribute to medication adherence may be more successful at following instructions of the providers.

Depression is common in the outpatient setting and particularly prevalent among those with multiple health problems.21 Depressed patients are less likely to follow through on medical recommendations,22 possibly because of hopelessness and lack of confidence in the effectiveness or worth of the treatment. Depressed patients also are likely to be isolated, lacking the social support necessary for adherence. The medication regimens for depression are frequently complex and often medication alone is insufficient for treatment.

The cost of medications is recognized as a common reason for medication poor adherence.3,5,23,24 With the Affordable Care Act, more patients are eligible for insurance but still may not be able to afford it, or may have insurance that does not cover the cost of medications. Even those with prescription drug benefits are often charged high copayments for each medication, which may represent a significant portion of a low-income patient’s monthly budget. Some health plans and systems will not pay for certain medications without a prior authorization, which requires patients to self-advocate, complete complex forms, and successfully negotiate alternatives with their clinician. Patients taking medications for chronic conditions may try to make their medications last longer (e.g., skipping doses, taking daily medications every other day), or fail to fill prescriptions when they are experiencing acute financial constraints.

Studies have shown that although clinicians understand that the cost of medications may affect adherence, they rarely initiate conversations about this barrier. Paradoxically, when they do, discussions frequently are not targeted to those patients most likely to have financial problems. Additionally, physicians often lack adequate knowledge of insurance and formulary restrictions to change their prescribing patterns, which could alleviate some cost burdens.25,26,27

Pharmacists are important resources for patients and other health-care providers to assist with medication costs. As an example, pharmacists can provide counseling for patients signing up for Medicare Part D to choose plans that cover their medications for low co-pay and prescription coverage plan fees.

Alcohol or illicit drug use is an important independent factor contributing to poor adherence, and may be more prevalent in patients challenged by depression or social isolation, which further affect adherence. Patients actively using illicit drugs or alcohol may be prone to erratic use or nonuse of prescribed medications. The use of illicit drugs or alcohol may worsen the conditions that their medications were prescribed to treat (e.g., hypertension, depression). The advent of effective pharmacologic-based treatments for addictions has led to efforts aimed at improving adherence among patients with dependence on illicit drugs or alcohol.28

After leaving his job, Mr. Cruise lost his private health insurance. Mr. Cruise began receiving his care at the public hospital and because of formulary differences had to switch from one type of beta-blocker, which is taken once a day, to another type of beta-blocker, which is taken twice a day. Further, the medications that he takes at home have been changed during each of his four hospitalizations.

Navigating the health-care system can be overwhelming as patients try to determine where to obtain the services and resources needed to maintain their health. These systems can be an academic medical center, a community hospital, a government-run hospital, a neighborhood clinic, a pharmacy, a mobile clinic van, or a traditional healer’s hut. The environment in which patients and clinicians discuss health-care recommendations can either support adherence or undermine it. The following are factors within the health-care system that may contribute to poor adherence.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree