Source: Ref. (1).

Definition of Community

Communities are generally defined by geographic boundaries such as villages, towns, or cities, but they can also be defined using smaller geographic limits such as zip codes, neighborhoods, or census tracks. Communities are more broadly defined as groups of people who share common characteristics and have existing relationships or opportunity for interaction (9, 10). Therefore, we do not have to follow a strict geographic definition and can extend our definition to worksites, schools, and even to patients that have some common disease or disability such as diabetes. However narrow or broad a definition we adopt, we need to have a clear understanding of our target community before starting any assessment. Often, the identification of a community is straightforward, such as a particular town, or a group of patients attending a specific program. In other cases, such as when we talk about neighborhoods, the boundaries are less well defined. In these circumstances one may need to approach community leaders and members to get more specific information and arrive at a consensus definition.

The Burden of Obesity in Communities

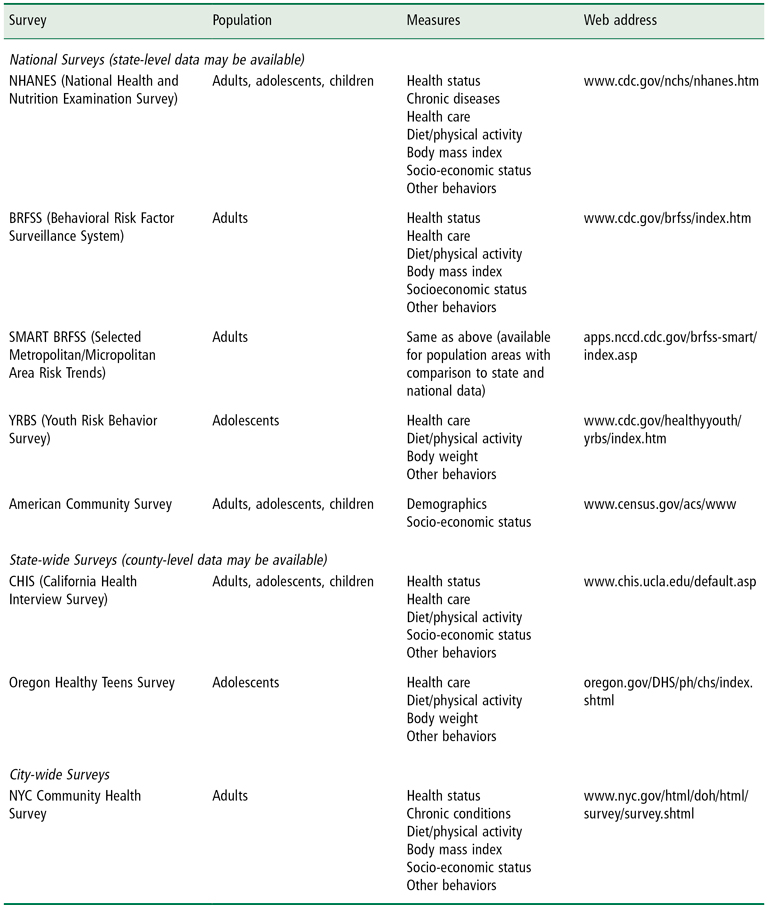

The first step in obesity prevention and control is to conduct a needs assessment; that is, to measure the prevalence of obesity in a population and identify whether there are segments of the population that are most affected. Who are the groups with the highest prevalence of obesity? Is the population meeting dietary and physical activity recommendations? What groups are most at risk? Is there evidence of disparities based on ethnic or socio-economic characteristics? There are two basic approaches for data collection, based on whether one will directly collect data (primary data collection) or extract data from existing national or local databases (secondary data collection), such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) or the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey (BRFSS).

Primary data collection entails collecting information on relevant factors by examining and interviewing participants directly, while secondary data analysis involves the use of existing data sets collected by other institutions and perhaps for different purposes. Examples of existing data sources are listed in Table 14-1. Each approach has its advantages and limitations. Primary data collection is generally more expensive and may take considerable time, while secondary analysis of data already collected may be cheaper and faster. Some disadvantages to planning to use secondary data are that data for local communities may not be readily available, key information may be missing, or the quality of the information may not be the best, if the data were collected for other purposes, such as administrative. Therefore, decisions have to be made on which approach to follow, taking into consideration the main goals of the assessment, existing resources and funding, and whether the information needed is publicly available or not.

Table 14-1 Examples of Existing National and Local Surveys

Community Indicators Related to Obesity

Before the start of any data collection we need to select and define relevant health indicators that will give us a clear picture of the problem in our community. To this end, we need to define what we mean by obesity, using definitions that are standard and appropriate for our particular population. For example, the parameters that will determine who is carrying excess weight will be different for adults and children, and among children, these parameters will differ according to sex and age. The most commonly used indicator of obesity is body mass index (BMI). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines adults as overweight when their BMI is between 25 and 29.9, and as obese when it is 30 or greater. For children and adolescents, the CDC uses age- and sex-specific BMI values to define youths as overweight if their BMI is between the 85th and 94th percentile for age and sex; youths with BMIs at or above the 95th percentile are considered obese.

Prevalence

The prevalence of a certain condition or risk factor is measured by counting the number of people with the condition of interest and dividing by the total population. For example, to calculate the prevalence of obesity in people in a particular community, we determine the number of people that have a BMI of 30 or greater and divide this number by the total number of adults in that community. The prevalence of obesity can also be calculated for each sex. For example, to measure the prevalence of obesity in females, we determine the number of women with a BMI of 30 or greater and divide that number by the total number of women in the community.

The prevalence of overweight or obesity provides us with a measure of the burden of these conditions in the population. Generally, measures of prevalence are used for planning purposes to plan for health services that a community may need; i.e., a high prevalence of obesity in a community will suggest the need for a weight management program in that community. It also gives us clues about the public health importance of obesity; a greater prevalence will indicate how widespread the condition is and demonstrate the need for preventive interventions. The prevalence of overweight and obesity can also be useful as a means to identify the groups of people most affected, since one can calculate the prevalence by sex, age group, and race/ethnicity.

Incidence

Incidence measures the new cases of a disease or condition that occur over a specified period. Calculating incidence is necessary if we want to know the factors that increase the risk of overweight or obesity in a population. Thus, we need to follow subjects who are not overweight and obese over a period of time, to measure how many of them develop obesity during that time. The incidence of obesity would be calculated as the number of new cases that occurred during that period divided by the total population at risk at the beginning of the period.

Weight-Related Lifestyle Behaviors

Knowing how many people are overweight or obese and which groups experience greater rates of overweight and obesity does not describe the public health burden of this problem in all its dimensions. The assessment of factors that are associated with excess weight in the community is also necessary to identify potential areas of intervention. Dietary factors associated with obesity include increased portion sizes, eating at fast-food restaurants or consuming food prepared away from home, having meals in front of the TV, and high soda consumption. Decreased physical activity and increased sedentary behaviors, such as driving instead of walking to school, spending time watching TV, and playing video or computer games, have also been shown to be associated with increased weight in people of all ages (2). Other factors contributing to obesity that may be useful to assess are the percentage of the population consuming the recommended number of daily servings of fruit and vegetables, and the percentage meeting recommendations for physical activity.

Demographic and Socioeconomic Indicators

There is growing evidence that individuals of minority groups and low socioeconomic status (SES) are most affected by the epidemic of obesity. Data from the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) show that African American women are twice as likely to be obese as their White counterparts, while Mexican American boys are 70% more likely to be overweight than White boys (11). In addition, an analysis of NHANES from 1971 to 2004 showed trends in overweight that are disproportionately higher among adolescents from families living in poverty. Similarly, there was an increase in the percentage of calorie intake from sweetened beverages that was larger among adolescents from poor families (12). Furthermore, recent data from the New York City Youth Risk Behavior Survey indicate that the prevalence of some health behaviors differs by neighborhoods (13). Adolescents living in boroughs with a higher proportion of low-income families have higher prevalence of obesity are less likely to eat the recommended number of servings of fruit and vegetables, and are less likely to attend physical education classes (13). Among youths aged 12–21 years, Lee and colleagues (14) reported that living in neighborhoods characterized by low SES was related to poorer dietary habits, while living in urban areas or neighborhoods with high Hispanic concentrations was related to better dietary behaviors, independent of individual demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. Black/White differences in dietary behaviors were attenuated after adjustment for neighborhood SES. Other examples of socioeconomic indicators include participation in the WIC program, education level, participation in free/reduced-price school lunch programs, and prevalence of food insecurity (Table 14-2).

Table 14-2 Examples of Community Indicators

| Socio-demographic |

|

| Built environment |

|

| Social environment |

|

Environmental Indicators

There is significant evidence that the environment shapes individuals’ dietary and physical activity patterns and contributes to the obesity epidemic (2). Recent research has shown that supermarkets are disproportionately located in wealthier and predominantly White areas (15). Data from the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study have shown that African Americans living in areas with supermarkets had healthier diets than those living in areas without one (16). In addition, the availability of more healthful foods is related to healthier intake patterns in individuals living in the area (17). Research from the transportation and urban design fields has reported that residents of sprawling counties were less likely to walk during leisure time and were more overweight than residents of compact counties (18). Residents from communities with higher density, greater connectivity, and more mixed land (residential and non-residential) use have higher rates of walking and biking than those from low-density, poorly connected neighborhoods (19). Other research has indicated that the number of physical activity resources (e.g., parks, sport facilities, fitness clubs) varied by neighborhood SES; low- and medium-SES neighborhoods had fewer facilities than high-SES neighborhoods (20). Similar findings have been reported for adolescents. Those in lower-SES and predominantly minority areas have less access to recreational facilities, and decreased access to these facilities is associated with decreased levels of physical activity and increased overweight (21). The aesthetic quality of the area and friendliness of the facilities have been associated with recreational walking (22). Conversely, unsafe environments have been found to be inversely associated with physical activity in adults (23) and children (24).

Inequalities in the access to healthful foods have also been reported. One study compared the availability of diabetes-healthy foods in stores of two adjacent neighborhoods in New York City, one affluent with a predominantly White population, the other low-income with a large minority population. The study found that residents in the low-income neighborhood were more likely than residents of the more affluent neighborhood to have stores that did not stock recommended foods and were less likely to have stores on their blocks that carried recommended foods (25). Moore and Diez-Roux examined the type of food stores in relation to neighborhood characteristics and demonstrated that stores carrying healthful foods were less common in poorer areas compared to richer areas, and less common in neighborhoods that were predominantly Black or Hispanic (26).

Another aspect of community environment is related to the social resources of the community, how members of the community are integrated, their sense of belonging and degree of organization. This social environment influences health behaviors through shaping community norms and patterns of social control, disseminating knowledge about health behaviors, and providing opportunities to engage in particular behaviors (27, 28). Aspects of the social environment are collectively described as social capital. Communities with high social capital have healthier behaviors and better health outcomes. Several studies have shown that social integration, as measured by individuals’ social networks, is associated with reduced cardiovascular disease mortality, whereas social isolation is related to greater mortality and greater incidence of coronary heart disease (29–31). More recent studies have reported that individuals with stronger social networks have diets richer in fruits and vegetables and are more physically active than individuals with weaker networks (32). Communities that are better organized, where community members look out for each other and intervene when trouble arises, show reductions in premature mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality (33, 34). Higher levels of social cohesion or collective efficacy, as this indicator of community organization is often called, have been associated with less smoking (35) and moderate intake of fruits and vegetables (36) in adults, and better perceived health (37) and lower BMI in adolescents (38).

Methods of Community Assessment

Sampling

In most circumstances, it is not feasible to study all individuals of a given community. Instead, a sample of the population is selected and measurements are performed on those individuals only. The method used to select participants that are representative of the population in the community is referred to as sampling. Often investigators recruit volunteers for their studies (a “convenience” sample); however, the use of volunteers may introduce bias into the study. Generally, volunteers are healthier, have healthier behaviors and use more preventive services, and do not represent the general population. Therefore, results from studies using convenience samples are difficult to generalize to the rest of the population. This problem is evident in intervention studies that include mostly White individuals for which the later intervention in other ethnic groups does not have the same success, possibly because the original intervention did not take into account barriers that other populations may have or because the intervention is not as well accepted.

There are four basic sampling methods (39): simple, random sampling, in which each individual has the same probability (chance) to be included in the sample; systematic sampling, in which participants are selected from a list of potential participants at regular intervals (e.g., every 3rd, 4th, or 10th individual); stratified sampling, in which the population is first separated into groups (e.g., females and males) and then simple random sampling is conducted separately for each group; and cluster sampling, by which groups (e.g., schools, households) are first sampled and then only people in those groups are included in the study.

Study Designs Used in Community Assessment

Cross-Sectional Studies

Cross-sectional studies provide a snapshot of the distribution of risk factors and diseases in the population (40). The prevalence of a particular risk factor or disease is calculated for a given community at a particular point in time. In contrast to other study designs, in cross-sectional studies individuals are not sampled based on their disease status or presence of a particular risk factor. In cross-sectional studies, all members of a community, or a sample of them, are examined to determine whether they have the disease of interest or the risk factor. Cross-sectional studies are very useful from a public health point of view because they provide a picture of the burden of a particular disease (e.g., diabetes) in a population and measure how prevalent risk factors, such as overweight, are in the population. However, because disease and risk factors are measured simultaneously, a limitation of this type of study is that it cannot establish temporality, that is, whether the presence of the risk factor preceded the occurrence of disease (see Table 14-3).

Table 14-3 Strengths and Limitations of Different Study Designs

| Study Design | Strengths | Limitations |

| Observational Studies | ||

| Cross-sectional | Often based on a representative sample of the general population Provides estimates of prevalence of risk factors and diseases Faster and cheaper than cohort studies | Cannot show whether risk factor preceded disease Incidence-prevalence bias |

| Case-control | Relatively quick and inexpensive Is of particular value when the disease is rare Can examine multiple risk factors for a given disease | Is inefficient for the evaluation of rare exposures Cannot directly compute incidence rates Temporal relationship may be difficult to establish Susceptible to selection and recall bias |

| Cohort | Is of particular value when exposure is rare Can examine multiple effects of a single exposure (same cohort may address risk of CVD or cancer) Can address temporal relationship If prospective, minimizes bias in the ascertainment of exposure Allows direct measurement of incidence rates | Inefficient for rare diseases If prospective, can be extremely expensive and time-consuming If retrospective, requires availability of adequate records Validity of results can be seriously affected by losses to follow-up |

| Experimental Studies | ||

| Randomized clinical trials/community trials | Directly addresses causality Good internal validity (less potential for biases) Randomization ensures that baseline characteristics will not act as confounders | Limited generalizability Bias may arise when there is lack of compliance and a large loss to follow-up (Intention-to-treat analysis) Very expensive |

An example of a cross-sectional study is the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), in which a representative sample of the population has a comprehensive examination and completes questionnaires about their lifestyle behaviors. This survey reports on the prevalence of overweight and obesity, dietary patterns, and physical activity levels in the population of the US. The Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) is another example of a national cross-sectional survey. The YRBS is a school-based survey of adolescents living in the US, and reports on the prevalence of lifestyle behaviors such as smoking, drug use, and fruit and vegetable intake, as well as physical activity levels.

Case-Control Studies

In case-control studies, individuals are selected based on their disease status (40, 41). Thus, before enrollment (or at enrollment) potential participants are examined to determine the presence of a particular disease. Individuals with the disease are classified as cases and people without the disease are classified as controls. In each group, the presence of risk factors is ascertained either by medical exam (e.g., high blood pressure), review of medical records (e.g., glucose levels), or administration of a questionnaire (e.g., family history of diabetes). The odds of having the risk factor are calculated for cases and controls and compared by calculating the odds ratio (OR). This approach is widely used in medical research and epidemiological studies due to its advantages. Since the selection of subjects is based on having the disease of interest, we do not need to wait until participants develop the disease, making case-control studies faster and less costly than longitudinal studies. This is particularly important for diseases that are rare or have a long latency period, like certain cancers.

Cohort Studies

Cohort studies (also known as prospective or longitudinal studies) select participants based on their exposure to a particular risk factor. Individuals with and without the risk factor of interest are followed for a period of time (months, years) (40, 41). At the end of the follow-up period, the incidence of disease is compared in the two groups and the relative risk can be calculated. A relative risk greater than 1 indicates that the risk of developing the disease is greater in the exposed group compared to the unexposed. Often in this type of study a defined population, such as a given community, is selected before knowing the exposure status of its individuals. Residents of the community are then examined or interviewed to assess which individuals are exposed to the risk factor, and then they are all followed for several years to measure the occurrence of disease among the exposed and unexposed groups.

The Framingham Study is the one of the best-known examples of this approach. In this study, residents of Framingham, Massachusetts between 30 and 62 years old were followed for several decades during which period their risk factors were measured, including smoking, obesity, high cholesterol, and high blood pressure. The occurrence of cardiovascular disease was later assessed in people with and without those risk factors. The Framingham Study is considered a landmark study because it helped identify the major risk factors that put individuals at risk of cardiovascular disease.

Ecological Studies

The studies described above commonly use individuals as the unit of analyses; that is, all assessment of exposure and disease occurrence are performed at the individual level, and inferences about the relationships are thus pertinent to the individual (40–41). Ecological studies are a particular approach in which the unit of interest is the group. Assessments of exposures and disease occurrence are performed at the group level—for example, for a community, a state, or a country. This type of study is more appropriate for examining processes that occur at the societal level, such as public health policies. Ecological studies compare rates of disease in a community and prevalence of risk factors in those same communities. An example of such analysis is measuring the intake of saturated fat and the incidence of a disease such as cancer in several communities and calculating the correlation between average saturated fat intake and the rate of cancer. The major limitation of ecological studies is that the link between individual exposures and disease cannot be established. One may observe a correlation between the prevalence of disease and the risk factors and infer that there is a causal association when in fact those individuals who were exposed to the risk factor were not the same individuals who have the disease of interest. This is termed an ecological fallacy. Another limitation of ecological studies lies in the difficulty of controlling for potential confounders, other unmeasured risk factors that may have a role in the occurrence of a disease.

Community Intervention Studies

Community interventions are a type of experimental study in which entire communities are randomized to a particular intervention (e.g., mass media education program) or to the control group (41). Using a random process to assign communities to the intervention or control group gives all communities an equal chance to receive the intervention. The purpose of randomization is to make sure that baseline characteristics are similar for the intervention and the control communities, and thus, that the effect observed can be attributed to the intervention or program. Community interventions are an extension of randomized clinical trials (RCT); the difference is that in randomized, controlled trials individuals and not groups are randomized to the intervention (e.g., drug or behavioral program). Community interventions can be conducted in smaller settings such as worksites, schools, or community health care centers and may not necessarily include large communities such as a town or city.

There are circumstances when randomization is not feasible. When assignment of the intervention is not by randomization, community interventions are referred to as quasi-experiments (42). The main limitation of quasi-experiments is that communities receiving the intervention may differ from control communities in other factors that can be related to the outcomes of the trial and thus affect the results. For example, the success of a nutrition education program may not be due to the program itself, but to higher education or better access to healthy foods of the communities assigned to the intervention.

The use of control groups is preferable; however, in some circumstances it is not possible to withhold prevention programs for ethical reasons or because participating communities expect to have a direct benefit from the study. As alternatives, control communities may consist of a waiting list in which communities are followed without intervention for a period of time and after the waiting period receive the intervention; control communities may receive a minimum intervention (e.g., printed materials) and not the full enhanced intervention that will be tested; or communities may be randomized to an alternative intervention that is absolutely different from the program being tested (e.g., receiving an injury prevention program instead of a nutritional education program).

The controlled conditions of clinical trials make it difficult to generalize their results to the settings where the programs are most relevant. Often participation in clinical and community trials involves participants that are highly motivated and organized, which may not be the case in public health practice for the majority of communities. Thus, it is generally a great challenge to implement a program shown to be effective in the context of a randomized trial, especially in the case of complex or high-intensity behavioral interventions, and make them work in other communities outside the trial.

To evaluate public health interventions, a RE-AIM approach has been developed. It addresses factors that are beyond the traditional measure of effectiveness and incorporates factors related to the target population, implementation, and maintenance of the intervention. This approach is considered a more realistic evaluation of public health interventions (43, 44). The RE-AIM framework (see Table 14-4) includes five concepts that address individual and organizational factors: Reach, which assesses participation rate and factors associated with it; Efficacy, which assesses the impact of the intervention (e.g., deaths prevented, behavioral change); Adoption, which reports on the proportion of settings that will adopt the program; Implementation, which measures the extent to which the intervention is implemented as intended; and Maintenance, which addresses sustainability of the program over time. Using these concepts, we could evaluate the extent to which the intervention could be expanded to the general population or implemented in different settings.

Table 14-4 RE-AIM Evaluation Dimensions

Adapted from ref. (43).

| Dimension | Level |

| Reach (proportion of the target population that participated in the intervention) | Individual |

| Efficacy (success rate if implemented as in guidelines; defined as positive outcomes minus negative outcomes) | Individual |

| Adoption (proportion of settings, practices, and plans that will adopt this intervention) | Organization |

| Implementation (extent to which intervention is implemented as intended in the real world) | Organization |

| Maintenance (extent to which a program is sustained over time) | Individual and organization |

Novel Approaches to Community Assessment

Mixed Methods

Qualitative research (see Table 14-5) has been used for several decades to help understand behaviors, attitudes, and perceptions related to health. Investigators use direct observation, interview key people, and take life histories to identify how and why certain behaviors or processes occur. In more recent years, a new methodology is being developed to integrate quantitative and qualitative research. The rationale for conducting such mixed-methods studies is to provide a more comprehensive view of a public health problem when neither a quantitative nor a qualitative method used alone is sufficient to capture all of its dimensions. The integration of these two methods involves collecting qualitative and quantitative data concurrently or sequentially. The interpretation of the research findings is also integrated (45–47).

Table 14-5 Qualitative Data Collection Methods

| Direct observation—participants are observed in their normal, daily life activities. |

| Key informants interviews—leaders of a community or organization are interviewed. |

| In depth-interviews—informal interviews, guided by few broad topics. |

| Semi-structured interviews—a questionnaire is used; allows for open-ended questions and elaboration of responses. |

| Focus groups—a topic is discussed among group participants; guided questions and probes are used. |

This mixed approach is used to refine instruments that will be used in quantitative research and to expand the information obtained with quantitative methods (47). For example, quantitative research might show that a high proportion of low-income individuals do not meet the Healthy People 2010 guidelines for healthy eating, but would offer little insight into the reasons why. Conducting focus groups (qualitative research) may inform investigators about various barriers people face in following a healthier diet.

Case Study: Developing the background for implementing an intervention

Ms. Green has just started her new job as the head of the Nutrition Department at the town’s City Hospital. She has read recent reports about the epidemic of childhood obesity in the country and wants to find out whether this is a problem in her community. She goes to the CDC webpage to get the most recent statistics and learns that according to the last National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES)1 33% of children ≥6 years old are overweight (BMI ≥85th percentile of the CDC growth charts). Among children aged 6–11 years, the prevalence is higher in Mexican American (43%) and non-Hispanic Black (37%) children compared to non-Hispanic White children (32%). Similar disparities are observed in children 12–19 years old.

Ms. Green also goes to the website of her local health department, but they don’t have the prevalence of overweight for children. She holds meetings with pediatricians at her hospital and they express their concern about what they see in clinical practice: more and more children are overweight and the treatment is challenging, they don’t have the resources or the time needed to address this issue. Ms. Green knows that before raising the need for a child weight management program with the administration of the hospital, she needs to know the extent of the problem in her hospital. She decides then to enlist the help of students in nutrition and residents in pediatrics to do a chart review and obtain the height, weight, sex, and age of the children who sought ambulatory care at the hospital during the last month. They review 1,000 charts and use the CDC BMI Child and Teen Calculator2 and find that 40% of children 6–15 years old have a BMI ≥85th percentile, and 17% a BMI ≥95th percentile.

Ms. Green meets again with the pediatricians and the administration and they agreed that the prevalence of overweight and obesity is high, but the administration is not sure about putting a lot of resources into a program without knowing whether it would be acceptable for parents. Ms. Green, with the help of students, conducts a survey among parents while they wait for their children’s appointment to find out the level of awareness about obesity in their children, and their children’s lifestyle behaviors. Results from the survey tell her that more than 90% of parents of overweight children did not know they children are overweight, 85% do not know what the recommendations are for daily intake of fruits and vegetables, 50% of children watch 3 or more hours of TV per day, 30% of children do not engage in moderate/vigorous physical activity, 60% eat at fast food restaurants three or more times per week, and 40% of children drink three or more sodas per day. The survey also indicates that 20% of parents with an overweight child are interested in learning more about healthy lifestyle behaviors and helping their children achieve a healthy weight.

Ms. Green believes that the results of the survey strongly indicate the need for a weight management program for overweight children. She conducts a literature search for successful programs, and learns that family-oriented, comprehensive behavioral programs that involve educational sessions work the best. Since she does not know if such programs would work in her population, Ms. Green invites parents of overweight children to a focus group to discuss the acceptability of a comprehensive behavioral program, the potential barriers for participation, and the factors that would make parents and their children participate. Ms. Green presents all these findings to the administration of the hospital and six months later the weight management program is up and running.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. High body mass index for age among US children and adolescents, 2003–2006. JAMA 2008; 299: 2401–5.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree