Associations between psychiatric disorder and offending

Lindsay Thomson

Rajan Darjee

Introduction

The associations between psychiatric disorder and offending are complex. There has been a great deal of research into certain disorders and violent offending particularly over the last two decades. In summary, this has found a clear and consistent association between schizophreniform psychoses and violence, the importance of premorbid antisocial behaviour in predicting future violence, and the adjunctive effect of co-morbid substance misuse and antisocial personality disorder in the prevalence of violence. In addition, it has allowed the development of neuropsychiatric models to begin to explain violence in the context of mental disorder. Substance use disorders and learning disability are discussed in Chapters 11.3.2 and 11.3.3.

Mental disorder and offending: a problematic relationship

Criminal behaviour is common in our society but there is evidence that violent crime rates have declined in Europe and North America over the last decade.(1) Mental disorders are also common. It is important to study the overlap between mental disorder and offending to consider those mental health and criminogenic factors that may be amenable to change. The social and economic factors relevant to offending are discussed in Chapter 11.2.

Before considering any associations between mental disorder and offending it is useful to consider the methodological problems in studying these:

Offences are man-made concepts and not static. For example, many jurisdictions have created laws against stalking in the last twenty years which did not previously exist.

Psychiatrists see a limited range of offenders but often base their research on these.

Research is generally carried out on a captive population in prison or secure hospital. Offenders in these settings are likely to include those with characteristics that disadvantage them in the criminal justice system, for example ethnic status, low economic status, homelessness, unemployment, and mental illness.

The generalizability of any findings must be queried given that offending is dependent on the wider social context such as rates of unemployment or crime, prevalence of substance misuse, and weapon carrying culture.

It can be difficult to standardize populations studied, and severity of crimes.

Criminal and mental health records may be unreliable.

Evidence for neurobiological determinants of offending or aggressive behaviour

There is resistance to any oversimplified idea of seeking a genetic or neuropsychological explanation to offending behaviour as a whole but research in this area is expanding slowly. Neuropsychological abnormalities are commonly found in offenders and there is evidence for specific brain deficits in aggressive or violent behaviour.(2) These findings include:

An association between specific traumatic damage to the frontal lobes, particularly orbitofrontal injury, and poor impulse control and aggressive outbursts.

Abnormalities on neuropsychological tests of frontal lobe function in aggressive and antisocial subjects, indicating prefrontal executive dysfunction.

Abnormalities found in clinical neurological testing of offenders. Antisocial behaviour is associated with EEG abnormalities particularly frontal slowing and these are commonly found in more than half of prisoners with a history of repetitive violence. Clinical signs of frontal lobe dysfunction are also associated with recurrent aggression.

Neuroimaging changes. Structural and functional studies examining patients in forensic services and patients with antisocial personality disorder have consistently found changes in the frontal lobes of aggressive patients, typically reduced prefrontal cortical size and activity. Predatory rather than impulsive, emotionally charged (affective) perpetrators of homicide show functional patterns of blood flow similar to controls suggesting that these neuroimaging findings are relevant to impulsive or affective aggression rather than premeditated, purposeful violence. Two groups of people with aggressive behaviour are postulated: the first with an acquired frontal lobe lesion due to injury or disease which impairs social judgement, risk avoidance, and empathy; the second, shows increased aggressive behaviour associated with deficits in executive functioning correlating with dorsolateral prefrontal dysfunction which may occur in foetal or birth brain injury, developmental learning disorders, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, substance misuse, and antisocial personality disorder with episodic aggressive dyscontrol.

In addition, there is evidence for biochemical abnormalities. Reduced serotonin function is largely related to impulsivity rather than directly to violence.(3) Serotonin has a role in emotional states such as impulsiveness, aggression, anxiety, and depression. This has provided potential avenues for treatment with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor medication.(4) Cortisol abnormalities have been recognized for a long time and more recently dietary insufficiencies have been explored.(5)

Lastly, the role of genetics in offending behaviour has been examined through family, twin, and adoption studies.(6) Adoption studies have found a consistent association between biological parents and adoptee for property offences but a more complex association for violent crime with a relationship discovered in the Danish birth cohort study between paternal violence and adoptee schizophrenia. A link between a genotype and disturbed behaviour was found in maltreated male children. Those with the gene encoding the neurotransmitter metabolizing enzyme monoamine oxidase A (MAOA) moderated the effect of maltreatment and had reduced antisocial behaviour in later life.(7) MAOA genes have a known association with aggression in animals and humans. The low expression variant leads to increased aggression, limbic volume reductions and hyper-responsive amygdala during emotional arousal with decreased reactivity of regulatory prefrontal regions.(8) Twin studies have shown that antisocial behaviour in early childhood particularly when associated with callous unemotional traits has a strong genetic influence which weakens in antisocial behaviour displayed initially in adolescence when environmental influences are important.(9)

Such changes are not a necessarily a cause for aggressive behaviour which is dependent on so many environmental factors, nor do they necessarily predict aggressive behaviour but they are important to study in that they indicate potential management strategies.

Clinical implications of the relationship between mental disorder and offending

The nature of the relationship between psychiatric disorder and offending is complex both at an individual and population level, and has important implications at both. Epidemiological data point to the following conclusions:

Schizophrenia, personality disorder, and substance related disorders are significantly overrepresented in offenders.

A number of factors associated with violence and offending in the non-mentally disordered are relevant to violence and offending in the mentally disordered.

Amongst offenders there is the need to provide psychiatric assessment and treatment for significant numbers of people with mental disorder.

Amongst mentally disordered offenders it is important to address criminogenic factors as well as providing traditional clinical treatment

Appropriate treatment and preventative measures may prevent some offending and violence by individuals with mental disorders

It is important to know and understand the epidemiological research, but also to know and understand the patient that is being assessed. Not all factors of relevance to offending in people with mental disorders act in the same way in every case, and some factors not found to be of relevance in study samples may be crucial in individual cases. There is no simple or straightforward approach to such an assessment, and narrowing one’s focus to a tick list of a few factors (perhaps from an actuarial tool) is at best lazy and at worst negligent. The psychiatrist should be able to articulate a formulation incorporating the factors which account for previous offending and which may be of relevance to future offending.

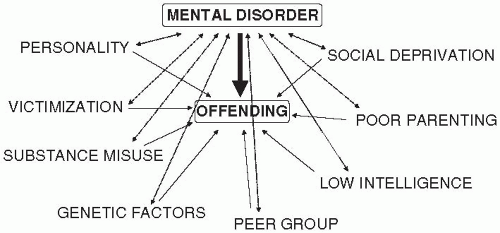

Every violent act involves a perpetrator, a victim, and a context, and this is no different where mental disorder is involved. A number of factors in the perpetrator, victim, and context in any violent incident are relevant to that violent act, and these three interact with each other. A simple example is that a drunk aggressive victim may frighten a suspicious impulsive perpetrator in the context of alcohol intoxication and an available knife. Where a person with mental disorder is violent one should not assume the former straightforwardly causes the latter. Sometimes mental disorder is the major determinant of an offence and at others mental disorder is entirely coincidental. In most cases mental disorder is one of a number of interacting factors (Fig. 11.3.1.1). Even where an offence seems explicable by psychotic hallucinations or delusions it is essential to consider wider factors (e.g. alcohol and substance misuse, social networks and personality).(10) A thorough assessment of these factors is crucial when evaluating criminal responsibility (see Chapter 11.1), assessing risk of future offending (see Chapter 11.15) and planning treatment for patients who have been violent. Treating mental disorder without addressing these factors will not adequately address the risk of further offending.

Scizophrenia and offending

For over a decade, studies have consistently shown a small but significant association between schizophrenia and violence with an

increased risk of violence of between 2–4 for men and 6–8 for women after controlling for marital status, socio-economic background and substance abuse.(11) The proportion of violent crimes in the population of Northern European countries attributable to individuals with severe mental illness is around 5 per cent.(12) A systematic review of mental disorder in 23, 000 prisoners found psychoses in 3.7 per cent of men and 4 per cent of women which was 2–4 times more than in the general population. Aggression in first episode psychosis occurs consistently in one-third of cases.(13)

increased risk of violence of between 2–4 for men and 6–8 for women after controlling for marital status, socio-economic background and substance abuse.(11) The proportion of violent crimes in the population of Northern European countries attributable to individuals with severe mental illness is around 5 per cent.(12) A systematic review of mental disorder in 23, 000 prisoners found psychoses in 3.7 per cent of men and 4 per cent of women which was 2–4 times more than in the general population. Aggression in first episode psychosis occurs consistently in one-third of cases.(13)

Fig. 11.3.1.1 A schematic representation of the complex interplay between factors of relevance to offending in people with mental disorder. |

Two patterns of aggression associated with schizophrenia are seen: firstly, those in whom features of conduct disorder (20-40 per cent) and later antisocial personality disorder predate the onset of overt schizophrenia; and secondly, those in whom violence occurs at a later stage.(11) Psychotic symptoms and violence in childhood are strongly related to later violence, as is a history of conduct disorder.(14)

Studies of people convicted of homicide have consistently shown an excess of schizophrenia with rates of 5–15 per cent.(15,16) Family members are significantly more likely to be the victim than strangers. Those with comorbid antisocial personality disorder are less likely to be actively psychotic at the time of the offence, and more likely to be intoxicated and to kill non-relatives.

Neurobiological correlates of schizophrenia and violence

Naudts and Hodgins(17) examined neurobiological correlates of schizophrenia and violence. The literature is small, as are the sample sizes, and the measures used are diverse. At least one-fifth of men with schizophrenia show antisocial behaviour from childhood onwards. Overall, these men perform better on tests of specific executive functions and verbal skills despite greater impulsivity; and worse on tests of orbitofrontal functions than men with schizophrenia alone. Structural brain imaging studies of men with schizophrenia and a history of repetitive violence found reduced whole brain and hippocampal volumes; impaired connectivity between the orbitofrontal cortex and the amygdala; and structural abnormalities of the amygdala. Functional neuroimaging studies found reduced prefrontal cerebral blood flow during completion of a test of executive function in violent patients. This reduction in blood flow may result in loss of inhibition and therefore aggression, or it may reflect that these violent men found the test easier and did not need increased blood flow to complete it. Studies of acquired brain lesions show that ventromedial orbitofrontal cortex is necessary for inhibiting impulsive decision-making and behaviour and for physiological anticipation of secondary inducers such as punishment. Studies at different ages suggest that an intact amygdala in early life is necessary for the normal development of this orbitofrontal system to recognize and process emotions. This fits with the work of Silver et al.(18) who found that patients with schizophrenia with a history of severe violence differ from non-violent patients with schizophrenia in their perception of the intensity of emotions but not cognitive function. Failure to assess the intensity of emotions may contribute to conflict generation, failure to recognize resolution signals, conflict escalation, and violence.

Clinical features

People with schizophrenia may be violent because of their psychotic experiences, impaired judgment and impulse control, or situational factors. The evidence of the effect of symptoms is conflicting however, probably because of the way questions are asked; failure to take account of affective symptoms; variation in the timing between symptoms and violence; failure to control for medication, compulsion and previous violence; and variations in statistical procedures.(19) Swanson et al.(20) in a study of 1 410 people with schizophrenia in a six month period found 19.1 per cent had been violent and this was serious in 3.6 per cent of cases. Positive symptoms increased the risk of minor and serious violence whereas negative symptoms decreased the risk of serious violence perhaps because these individuals lived alone. Serious violence was associated with psychotic and depressive symptoms, childhood conduct problems, and victimization. Severe psychotic symptoms and threatcontrol override (TCO) were antecedents of violent behaviour of patients in the community even after controlling for psychopathy and substance abuse.(21) TCO consists of persecutory delusions, passivity phenomena and thought insertion, resulting in perceived personal threat combined with loss of self control. Excessive perceptions of threat explained violence in people with schizophreniaspectrum disorder alongside a history of conduct disorder.(22)

Hallucinations, acute suicidal ideation, acute conflict and stressors such as separations or housing problems, and lack of insight have all been associated with an increased risk of violence.(23)

Co-morbidity

The likelihood of violence in patients with schizophrenia increases in the presence of comorbid substance use (3-fold in men, 16-fold in women) or personality disorder (4-fold men, 18-fold women).(11) Swanson et al.(20) found however, that the effects of substance abuse were non significant after controlling for age, positive symptoms of schizophrenia, childhood conduct problems and recent victimization thereby suggesting that the effects of substance abuse on violence may be mediated by these factors. There is a strong association between comorbid antisocial personality disorder and substance abuse in patients with schizophrenia with common origins in conduct disorder.(24) Further evidence for this is found in neuropsychological tests. Patients with comorbid schizophrenia and substance abuse perform as well as those with schizophrenia alone on neurological tests although it is known that the brains of men with schizophrenia are particularly sensitive to effects of drugs and alcohol. It has been suggested that these men belong to the antisocial group who do better on these tests at the onset of their schizophrenia.(17)

Management

The care of patients with schizophrenia and a history of serious violence is centred around ongoing assessment and management of factors contributing to risk of violence and treatment of the schizophrenic illness. Predictors of violence include recent assault, a previous violent conviction, lower educational attainment and attending special education, a personal and family history of alcohol abuse, and lower but normal range IQ.(25,26) The management of schizophrenia is discussed in Chapter 4.3.8 but in patients with a history of violence methods of legal compulsion for detention and treatment, and programmes to address comorbid and criminogenic needs are particularly important. There is evidence that cognitive behavioural therapy can modify delusional beliefs that have lead to violence(27) and that clozapine has a particular role in the treatment of aggression in patients with schizophrenia separate from its antipsychotic or sedative components.(28)

Outcome

There is no indication that deinstitutionalization has lead to increased offending by patients with schizophrenia. Rates of violence have increased but in proportion to the increase in society as a whole and with increased comorbid alcohol abuse.(29) Outcome studies of patients transferred from high security found a recidivism rate of 34 per cent and 31 per cent in England and Scotland respectively, and a violent recidivism rate of 15 per cent and 19 per cent after ten years.(30, 31) Patients with a primary diagnosis of schizophrenia during a follow up period of 8 years had a recidivism rate of 15 per cent and a violent recidivism rate of 5 per cent.

Delusional disorders

Delusional disorders are described in Chapter 4.4. There are a number of subtypes including somatic, grandiose, mixed and unspecified but it is particularly the jealous, erotomanic and persecutory forms that are associated with offending and violence. Individuals with delusional disorders remain organized allowing them to target and plan any violence more effectively. Sixty percent of people with delusional jealousy are violent towards their partners. In erotomania the patient has the delusional belief that s/he is loved from afar by another and may attack individuals perceived as standing between them and their loved one, or the object of their affections if they feel slighted. Erotomania is associated with anger, harassment, stalking, and violence.(32)

Delusional disorders are found in excess in homicide (6-fold increase) and are associated with stalking. Stalking is persistent harassment in which a person repeatedly intrudes on another in an unwelcome manner that evokes fear or disquiet. One study of stalkers found that 30 per cent had a delusional disorder, 10 per cent schizophrenia, less than 5 per cent bipolar disorder or anxiety; 50 per cent had a personality disorder and 25 per cent abused substances. The classification of stalkers is based on their motivation. It is the rejected stalkers who pursue ex-intimates for reconciliation, revenge or both (includes delusional jealousy); intimacy seekers (includes erotomania); and the resentful stalker who pursue victims as revenge for an actual or perceived injury (includes persecutory) who are most likely to have a delusional disorder. This is not the case for incompetent suitors or predatory stalkers. See Chapter 11.10

Risk of harm to others can be reduced by treating the individual’s delusional disorder with medication; controlling his or her environment by use of hospital or legal orders to restrict movement; and by advice to any potential victim on protective measures. There have been no randomized controlled trials of the treatment of delusional disorders but novel antipsychotics are now most commonly used due to their lower side-effect profile and better compliance, and it is recognized that pimozide has no particular role in the treatment of delusional disorder.(33) Cognitive behavioural therapy may assist compliance and insight but this has not been systematically demonstrated. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) interwoven with cognitive therapy has been reported as a treatment of morbid jealousy. It is essential to warn any identified potential victims and such a breach of confidentiality is permitted by medical governing bodies.

Organic disorders

Organic disorders may be related to offending directly because of the brain injury with disinhibition and impaired judgement, or secondarily to socio-economic deprivation and exclusion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree