Astroglial Mechanisms in Epilepsy

Christian Steinhäuser

Philip G. Haydon

Nihal C. de Lanerolle

Introduction

Currently available anticonvulsant drugs and complementary therapies are not sufficient to control seizures in about a third of epileptic patients. Thus, there is an urgent need for new treatments that prevent the development of epilepsy and control it better in patients already inflicted with the disease. A prerequisite to reach this goal is a deeper understanding of the cellular basis of hyperexcitability and synchronization in the affected tissue. Epilepsy is often accompanied by massive reactive gliosis. Although the significance of this alteration is still poorly understood, recent findings suggest that modified astroglial functioning may have a role in the generation and spread of seizure activity. In the following sections we detail properties of astrocytes as well as their changes that can be associated with epileptic tissue. Our goal is to provide an understanding of the working knowledge of this cell type with the long-term view of providing a foundation for the development of novel hypotheses about the role of glia in seizure disorders.

Basic Physiology of “Normal” Astrocytes

Before discussing details of membrane physiology of astrocytes, it is important to note that it is likely that there are different types of cells with astroglial properties within a given brain region, and that astrocyte properties may vary in different subregions. However, at this time we have only little understanding of the different properties of these cells and how heterogeneous these cell types are. In rodents, the majority of astrocytes express the astrocyte-specific protein, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP); have a high resting K+ conductance; are coupled in a syncytium through gap junctions, and have linear current/voltage relationships. A second type of cells, which we will also call astrocytes or astroglial cells, contains GFAP mRNA, but expresses a plethora of voltage-gated ion channels and are not coupled in a gap junction syncytium. It is likely that the functional impact of these two subtypes of cells with astroglial properties is distinct. For example, in the hippocampus the former cells express glutamate transporters, while the latter express α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionate (AMPA)-type glutamate receptors.80,125

Membrane Physiology

Astrocytes express almost the same set of ion channels and receptors as do neurons,67,108,120 although the relative strength of expression varies between the two cell types. For example, in astrocytes, K+ channel density by far exceeds that of Na+ channels, preventing generation of glial action potentials. Nevertheless, a glia-specific, or at least preferential expression, has been elucidated for some of these channels and carriers. Among them is Kir4.1, a subunit belonging to the family of inwardly rectifying K+ (Kir) channels. In the central nervous system (CNS) this channel is predominantly localized at distant astrocyte processes surrounding synapses or capillaries.58 Recent work suggests a colocalization of Kir4.1 with the water channel aquaporin-4 (AQP4), which in the brain and spinal cord is also expressed by astrocytes but not neurons. Increasing evidence indicates that a coordinated action of both channels is required for the astrocytes to maintain K+ and water homeo-stasis in the CNS.89,121 As illustrated in the following sections, dysfunction of these astroglial transmembrane channels appears to play a key role in epilepsy.

In contrast to the majority of mature neurons, astrocytes are usually coupled through gap junctions to form large intercellular networks. Astrocytic gap junctions are mainly formed by connexins 43 and 30 (Cx43 and Cx30) in a cell-type specific fashion. Through these networks astrocytes can dissipate molecules, such as K+ or glutamate, a process considered important to prevent their detrimental extracellular accumulation.116 Recent data suggest that the capacity of K+ clearance is only partially disturbed in the absence of astrocyte gap junctions, presumably because of the existence of “indirect” coupling of elongated astrocytic processes.126 Connexins also contribute to the propagation of intercellular Ca2+ waves, presumably by enhancing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) release, rather than by providing an intercellular pathway for signal diffusion.87 However, the pathologic impact of disturbed astroglial gap junction expression is not well understood yet.110,110a

Another main function of astrocytes is removal of neurotransmitters released by active neurons. Uptake of glutamate is accomplished by two glia-specific transporters, EAAT1 and EAAT2 (in rodents termed GLAST and GLT-1), the activity of which may shape the kinetics of receptor currents at some synapses.11,32 Compelling evidence suggests that disturbed glutamate uptake by astrocytes is directly involved in the pathogenesis of epilepsy, as discussed in the following sections.

However, astrocytes can also release neuroactive agents, including neurotransmitters. Several studies revealed that such a release is critically dependent on an increase of astroglial [Ca2+]i. Astrocytes express a plethora of neurotransmitter receptors that are coupled through G proteins (Gq) and phospholipase C to the release of Ca2+ from internal stores.56 Stimulation of neuronal afferents induces Ca2+ elevations within astrocytes,33,98 which can spread to neighboring astrocytes, demonstrating the presence of an astrocyte-to-astrocyte network.28,111 Thus, although astrocytes are electrically inexcitable, these glial cells contain a chemically based form of excitability that is bidirectionally linked to

neuronal activity.56 Though initially discovered in 1994,92 the past decade has seen many studies demonstrating that astrocytes release chemical transmitters (“gliotransmitters”), including glutamate, ATP, and D-serine.56,124 Although the mechanisms underlying astroglial transmitter release are open to debate, at least part of the release seems to occur through regulated, Ca2+-dependent exocytosis, a mechanism that in the CNS was previously thought to be exclusive to neurons.

neuronal activity.56 Though initially discovered in 1994,92 the past decade has seen many studies demonstrating that astrocytes release chemical transmitters (“gliotransmitters”), including glutamate, ATP, and D-serine.56,124 Although the mechanisms underlying astroglial transmitter release are open to debate, at least part of the release seems to occur through regulated, Ca2+-dependent exocytosis, a mechanism that in the CNS was previously thought to be exclusive to neurons.

What is the impact of transmitter release from astrocytes? Several reports suggested that gliotransmitters may activate receptors in neurons to modulate the strength of inhibitory and excitatory synaptic transmission13,50,66,93,94,132,135 (reviewed by 124). Importantly, because with their fine terminal processes single astrocytes reach tens of thousands of synapses simultaneously,25 the release of gliotransmitters may lead to the synchronization of neuronal firing patterns.6,49 The different gliotransmitters that are released from astrocytes have quite distinct functions. Glutamate, the first identified gliotransmitter,92 is able to modulate neuronal excitability6,49,117 through actions on the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor, as well as to modulate synaptic transmission.50 D-serine is a coagonist of the NMDA receptor. Released D-serine can bind to what has been termed the glycine-binding site of the NMDA receptor and, as a consequence, enhance NMDA receptor function. In the hypothal-amus, the amount of astrocyte-derived D-serine supplied to synapses can regulate which forms of synaptic plasticity occur. In conditions where little of the coagonist is supplied a long-term synaptic depression can result, whereas when D-serine is locally supplied to the synapse long-term potentiation results.91 The release of ATP from astrocytes can have a variety of functional actions. In cultures it has been shown that the release of ATP is important for mediating components of Ca2+ waves that propagate between astrocytes: During a Ca2+ elevation ATP is released from an astrocyte, which then has paracrine actions on neighbors, which induces further Ca2+ signals and ATP release.53 Because cell surfaces express a plethora of ectonucleotidases, once ATP is released it is rapidly hydrolyzed to adenosine. As a consequence, ATP that is released from astrocytes leads to synaptic modulation mediated by adenosine.94 In the hippocampus high-frequency activity of groups of synapses causes Ca2+ signals in neighboring astrocytes, which then release ATP, and after the hydrolysis to adenosine, cause a presynaptic inhibition of neighboring synapses.94 In this manner the astrocyte coordinates the strength of synaptic signaling. As illuminating as these studies have been, we still await an understanding of the functional consequences of gliotransmission on neural network function, processes such as learning and memory and ultimately behavior. Rapid forms of neuron–glia interactions seem also to be involved in the regulation of local blood flow as demonstrated in cortical brain slices where neuronal stimulation led to glutamate release, activation of metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) in astrocytes, and regulation of the tone of vessels contacted by processes of the stimulated astrocyte.86,112,136 Emerging evidence suggests that disturbances of these mechanisms are involved in the pathogenesis of epilepsy, as discussed below.

Several important aspects of neuron–glia interactions are not yet understood. Thus, as outlined above, recent studies corroborated the finding that astrocytes are heterogeneous with respect to antigen profiles and functional properties, but it is still unclear which type(s) of astroglial cells are activated and are capable of releasing transmitters, which transmitters can be released by astrocytes, which mechanisms these cells use for the release, and whether the efficiency of neuron–glia signaling changes during development. Intriguingly, a recent report presented evidence that a subtype of cells with astroglial properties even receives direct synaptic input from glutamatergic and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA)-ergic neurons.62 The physiologic impact of this type of interaction remains to be clarified.

Astrocyte Metabolism

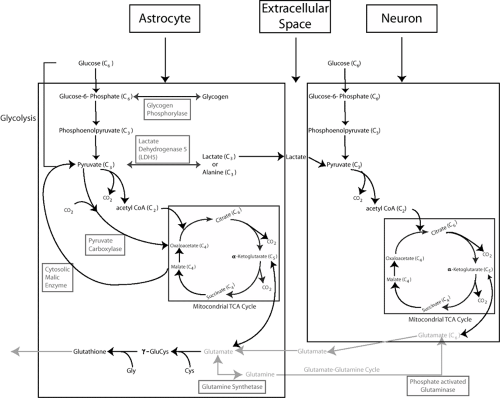

Astrocytes play an important role in the metabolism of the brain through their unique degradation of both glucose and glutamate.57 The astrocyte’s importance for these processes lies in their possession of some key enzymes not normally found in neurons. These enzymes are glutamine synthetase, pyruvate carboxylase, and cytosolic malic enzyme.

Glucose is the main energy source of the brain. It is a six-carbon chain molecule that is degraded to its end-products, carbon dioxide and water. The metabolism of glucose takes two stages. Glycolysis in the cytosol yields two ATP molecules and can occur in the presence or absence of oxygen, whereas oxidative metabolism in the mitochondria yields 36 ATP molecules per molecule of glucose through its conversion to acetylcoenzyme A (acetyl-CoA) and breakdown in the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle.57 Astrocytes, like neurons, are capable of metabolizing glucose through both pathways. The TCA cycle is limited by the fact that its intermediates continuously leave: Neuronal glutamate is lost to glia, glutamate is used for glutathione synthesis in astrocytes, and glutamine is used for GABA synthesis in GABAergic neurons.57 Such a loss of carbon skeletons without replenishment can impair neuronal ability to produce amino acid transmitters and the rate of oxidative metabolism. Astrocytes alone are capable of replenishing carbon skeletons because they, rather than neurons, possess the enzyme pyruvate carboxylase, which can de novo carboxylate each molecule of pyruvate to a molecule of oxaloacetate (four carbon atoms) that can be inserted into the TCA cycle to replenish it.

The glutamate released by neurons during excitatory synaptic activity is largely removed from the synaptic cleft by astrocytic glutamate transporters (cf. above). Once in the astrocyte, glutamate is converted to glutamine by the addition of ammonia, a reaction catalyzed by the enzyme glutamine synthetase that is found in astrocytes (and oligodendrocytes) but not neurons. The glutamine thus produced is released into the extracellular space where it accumulates in high concentrations (∼0.25 mM)54 and is returned to neurons. In the neuron, glutamine is hydrolyzed to glutamate, the reaction being catalyzed by the enzyme phosphate-activated glutaminase (PAG). Several lines of evidence show that glutamine produced by astrocytes is essential for the production of neuronal glutamate.57 This exchange of glutamate and glutamine between neurons and astrocytes is described as the glutamate–glutamine cycle.

Conversion to glutamine is not the only fate of astrocytic glutamate. With high levels of extracellular glutamate, some of the glutamate taken up by astrocytes can be deaminated or transaminated to α-ketoglutarate and then metabolized in the TCA cycle.82 Under conditions of high extracellular glutamate, α-ketoglutarate may also leave the TCA cycle as malate to be converted in the cytosol to pyruvate, catalyzed by the cytosolic malic enzyme, which is restricted to glia.83 Pyruvate can either be reintroduced into the TCA cycle via acetyl-CoA or be converted into lactate and exported to neurons.

Glial cells, especially astrocytes, also have a prominent capacity to produce lactate in the presence of normal oxygen levels.127 This process, also called aerobic glycolysis, is stimulated on exposure of astrocytes to glutamate.95 Further, mobilization of glycogen reserves in astrocytes by various neurotransmitters has been shown to result in enhanced lactate release.41 The presence of the lactate dehydrogenase 5 (LDH5) isoform in astrocytes favors conversion of pyruvate to lactate. Lactate is released into the extracellular space and used as an energy source by neurons. Thus, astrocytes act as a lactate source inside the brain, especially during enhanced synaptic

activity, and the concept of an astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle has been proposed.96 In vivo dialysis studies in sclerotic hippocampi have demonstrated increased levels of lactate along with glutamate during seizures.43

activity, and the concept of an astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle has been proposed.96 In vivo dialysis studies in sclerotic hippocampi have demonstrated increased levels of lactate along with glutamate during seizures.43

Astrocytes, rather than neurons, contain the cystine–glutamate exchanger.32 This transporter helps astrocytes to accumulate cystine, which is reduced to cysteine for the production of astrocytic glutathione.40 Synthesis of glutathione occurs primarily in astrocytes. In the process of glutathione formation, astrocytes release glutathione into the extracellular space, which is essential for providing neurons with the glutathione precursor L-cysteinyl glycine, formed from glutathione by the coenzyme γ-glutamyl transpeptidase.

These distinctive metabolic pathways in astrocytes are summarized schematically in FIGURE 1.

Astrocytes in the Pathology of Epileptic Foci

Neurons have been the primary focus of attention in the study of the pathology of the epilepsies, because ictal activity is generated by neurons. It is, however, becoming clear that glial cells, in particular astrocytes, may play a major role in the excitability generated at seizure foci.110a,117 With this finding in mind, re-examination of the pathology of seizure foci may indicate a significant astrocytic component in many seizure foci.

Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

Perhaps the most prominent seizure focus with a major astrocytic component is the sclerotic hippocampus in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). Hippocampal sclerosis has been associated with TLE, and the prevalence of this pathology has been variously estimated. Early autopsy studies found between 30% and 58% of TLE cases presenting with hippocampal sclerosis.20,77,109 Examination of specimens from patients who had undergone surgery for the control of medically intractable TLE showed a similar proportion. Falconer reported that about 43% to 47% of his patients suffered from Ammon horn sclerosis (AHS)23,47; the UCLA series of temporal lobectomies for TLE found hippocampal sclerosis in 65% of the cases.78 In the latter two studies, patients with hippocampal sclerosis had a better surgical outcome than those without it. Careful analysis of the pathology and electrophysiology of 151 hippocampi removed in the Yale surgical series revealed that about 60% of the specimens presented with AHS.34 After surgery, 84%

of AHS patients had an excellent (Engel class I), seizure-free outcome.

of AHS patients had an excellent (Engel class I), seizure-free outcome.

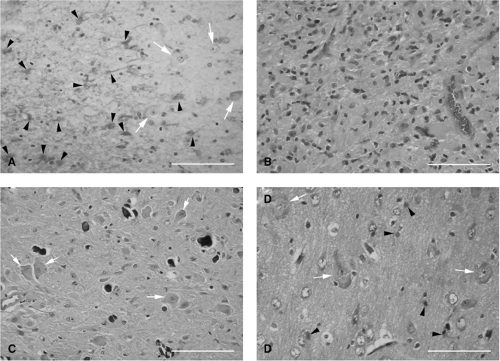

What is most striking about the sclerotic hippocampus is that it is significantly depleted of its neuronal populations but has an increased population of glia, especially astrocytes (Fig. 2A) and microglia. Anatomic and physiologic studies published to date35,110,110a indicate that astrocytes in the sclerotic hippocampus display many unusual characteristics compared to those of nonsclerotic hippocampi. However, neither the extent of the molecular uniqueness of astrocytes in the sclerotic hippocampus nor the molecular processes underlying their genesis and function are currently understood.

Mass Lesions

Seizures are a major clinical manifestation also of intracranial tumors, being observed in about 35% of cases.68 The majority of primary brain neoplasms are derived from glial cells and are collectively called gliomas. Gliomas are the most common among epilepsy-related tumors and are predominantly low grade. Among the epileptogenic gliomas, astrocytomas (Fig. 2B) are most frequent, being found in 50% to 70% of cases.68 Regardless of their type or grade, surgical removal of gliomas result in excellent seizure control (citations in 68). In hemimegalencephaly, a rare disorder closely associated with seizures, there is often diffuse proliferation of astrocytes in the cortex as well as subcortical white matter in addition to cortical neuronal abnormalities (Fig. 2D).

Tuberous Sclerosis

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a disease that is manifested due to mutations in the TSC1 and TSC2 genes of the human genome. Epilepsy occurs in about 90% of affected individuals.31 The pathologic substrates of TSC are also associated with astrocytes. Brain lesions of TSC are of three types: Cortical tubers, subependymal nodules, and subependymal giant cell astrocytomas (SEGAs). Cortical tubers show abnormal cortical lamination and are characterized by the presence of a proliferation of astrocytes in addition to dysmorphic neurons and eosinophilic giant cells (Fig. 2C).37,52 Subependymal nodules are also composed predominantly of dysplastic astrocytes and mixed-lineage astrocytic or neuronal components,37 giant cells, and, sometimes, calcium depositions.64 SEGAs also display astrogliosis, dysmorphic neurons, and giant cells. Thus, all three pathologies are associated with astrogliosis. Even the giant cells have astrocytic properties. Yamanouchi et al.131 divided giant cells into two subtypes: “Neuronlike giant cells”

and “indeterminate giant cells.” The majority of the latter were positive for GFAP, vimentin, and nestin, markers expressed by astrocytes, and rarely contained neurofilaments. In conclusion, brain lesions of TSC, in addition to other alterations, also seem to be associated with defects in astrocyte biology.

and “indeterminate giant cells.” The majority of the latter were positive for GFAP, vimentin, and nestin, markers expressed by astrocytes, and rarely contained neurofilaments. In conclusion, brain lesions of TSC, in addition to other alterations, also seem to be associated with defects in astrocyte biology.

Astrocyte Dysfunction Contributes to Seizure Generation in Temporal Lobe Epilepsy

The hippocampal seizure focus in TLE has been studied the most, compared to other seizure foci in the brain. Through these studies there is rapidly emerging a picture of astrocytes at the sclerotic hippocampal seizure foci as having unique structural and functional characteristics. In this section these characteristics are reviewed to exemplify some of the mechanisms through which they may contribute to seizure generation and compare them to what is known of astrocytes at other seizure foci (see Astrocyte Dysfunction at Other Seizure Foci section).

Voltage-Gated Na+ and Ca2+ Channels

Information about changes in Nav channel expression in experimental or human epilepsy is inconsistent. Comparative patch clamp analyses were performed in hippocampal specimens with and without significant astroglial sclerosis, surgically removed from patients with intractable TLE. Two papers reported enhanced Na+ current densities in human astrocytes from sclerotic specimens17,18 (Fig. 3), while no increase was found in another human study59 and in the hippocampus of kainate-treated rats, an animal model of TLE.61 It is conceivable that this apparent discrepancy reflects subregional differences because the latter two studies investigated astrocytes in the CA1 region while the aforementioned focused on the hilus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree