Autism Spectrum Disorders

Karen Toth PhD

Bryan H. King MD

Introduction and Background

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is the term now commonly used to describe three of the pervasive developmental disorders (PDDs): autistic disorder, Asperger disorder, and pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS). Rett disorder and childhood disintegrative disorder (CDD) also fall under the broader PDD umbrella. As the term suggests, ASD describes individuals across a wide range of symptoms, cognitive abilities, and adaptive functioning. A lifelong neurodevelopmental disorder, ASD is characterized by qualitative impairments in social interaction and communication, and the presence of restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped interests and behaviors. Our understanding of this complex disorder has changed dramatically since it was first described by Leo Kanner in 1943 and Hans Asperger in 1944. Research integrating diverse methodologies from the fields of neurobiology, cognitive and developmental neuroscience, developmental psychopathology, and genetics has shed light on the complex pathogenesis of this disorder and its heterogeneous phenotype. This chapter highlights the latest advances in autism research, while also providing useful tools for screening and detection of ASD in primary care settings. Finally, information on evidence-based assessment and treatment approaches and helpful resources for parents and professionals are provided.

Clinical Features and Diagnosis

The cognitive and behavioral deficits commonly seen in individuals with autism are perhaps best understood along a dimension of social communication functioning. However, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) is based on a categorical system, which is less useful for capturing the broader phenotype of a spectrum disorder such as autism.

Diagnostic Criteria and Differential Diagnosis

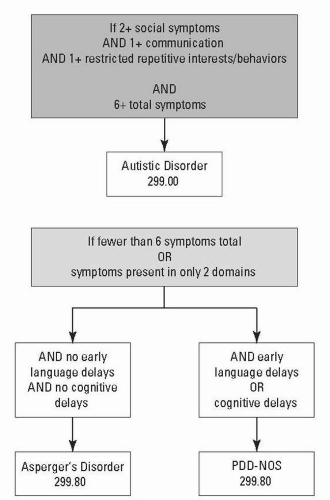

Autistic Disorder

The diagnostic criteria for autistic disorder, both early onset and regressive types, include a total of six or more symptoms across all three domains of impairment, with at least two symptoms in the domain of reciprocal social interaction, one in communication, and one in restricted, repetitive, and stereotyped interests and behaviors. Additionally, symptoms must be present by age 3 and are not better accounted for by Rett disorder or CDD. The diagnostic symptom list for the ASDs by domain, based on the DSM-IV-TR, is shown in Table 16-1.

Asperger Disorder

Just like autistic disorder, Asperger disorder is characterized by at least two impairments in the domain of reciprocal social interaction and at least one in the domain of restricted, repetitive,

and stereotyped interests and behaviors, using the symptom list provided in Table 16-1. However, for a diagnosis of Asperger disorder, there must be no early language delays (i.e., single words by age 2, phrases by age 3) and no clinically significant delays in cognitive or adaptive function. Finally, criteria are not met for another specific PDD, including autistic disorder. This means that if a child meets early language milestones on time and has no cognitive delays, but has six or more symptoms across all three domains of functioning, the appropriate diagnosis is autistic disorder, not Asperger disorder (in this case, the diagnosis can be further specified as “high functioning”). That being said, there is little empirical support for a clinically meaningful distinction between high functioning autism (HFA) and Asperger disorder, both in terms of symptom presentation and outcome. Further, the absence of early language delays in Asperger disorder does not imply that language acquisition is normal (e.g., there may be deficits in pragmatic [i.e., social use of] language, or use of overly formal or repetitive and stereotyped language), and as such this distinction remains problematic.

and stereotyped interests and behaviors, using the symptom list provided in Table 16-1. However, for a diagnosis of Asperger disorder, there must be no early language delays (i.e., single words by age 2, phrases by age 3) and no clinically significant delays in cognitive or adaptive function. Finally, criteria are not met for another specific PDD, including autistic disorder. This means that if a child meets early language milestones on time and has no cognitive delays, but has six or more symptoms across all three domains of functioning, the appropriate diagnosis is autistic disorder, not Asperger disorder (in this case, the diagnosis can be further specified as “high functioning”). That being said, there is little empirical support for a clinically meaningful distinction between high functioning autism (HFA) and Asperger disorder, both in terms of symptom presentation and outcome. Further, the absence of early language delays in Asperger disorder does not imply that language acquisition is normal (e.g., there may be deficits in pragmatic [i.e., social use of] language, or use of overly formal or repetitive and stereotyped language), and as such this distinction remains problematic.

TABLE 16-1 Diagnostic Symptoms of Autism Spectrum Disorders by Domain | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pervasive Developmental Disorder—Not Otherwise Specified

This diagnosis describes severe and pervasive impairments that do not meet full criteria for a specific PDD, and includes “atypical autism—presentations that do not meet the criteria for autistic disorder because of late age at onset, atypical symptomatology, or subthreshold symptomatology, or all of these.” Given this broad definition and the absence of minimum symptom criteria, it is no wonder that in recent years many children with social issues and/or pragmatic communication difficulties have been diagnosed as having a PDD. When considering a diagnosis of PDD-NOS, the clinician should assess for impairments in at least two of the three domains indicated in Table 16-1 to provide evidence of a pervasive disorder. Further, given that severe social impairments are a distinguishing feature of ASD, there should be evidence of marked impairments in social interest, social motivation, and social relatedness, and not merely deficits in interpersonal skills that are common to a number of disorders, such as attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and conduct disorder, among others. Figure 16-1 provides an algorithm to guide diagnostic differentiation.

Other PDDs

Rett disorder and CDD fall under the broader umbrella of the PDDs. In Rett disorder, development in the first 5 months of life is normal, followed by a regression involving deceleration of head growth, loss of previously acquired hand movements and social engagement, the development of stereotypic “hand-wringing” movements, poorly coordinated gait or trunk movements, and severe impairments in language and psychomotor development. CDD is characterized by a period of typical development for the first 2 years of life followed by a regression in language, social or adaptive skills, play, motor skills, and bowel or bladder control. Also present are qualitative impairments in two of the three domains affected in autism. The difference between autism with regression and CDD is that, in autism, the regression typically occurs between 18 and 24 months and, in CDD, the regression occurs after 24 months of age.

Symptom Presentation

Every child with autism is unique in terms of number and severity of presenting symptoms. Additionally, symptoms fluctuate across the lifespan.

Social Impairments

Deficits in social attention are primary in ASD. Infants with autism show impairments as early as 8 months of age in looking at others and orienting to name, as compared to infants with typical and delayed development. A deficit in joint attention—the ability to share attention with another person in regard to an object or event (e.g., pointing to show, following another’s eye

gaze to an object)—is a core early symptom of autism, present by 12 months of age. Children with autism also show early impairments in motor imitation, social imitative play (e.g., peek-aboo), and “theory of mind” or perspective-taking abilities.

gaze to an object)—is a core early symptom of autism, present by 12 months of age. Children with autism also show early impairments in motor imitation, social imitative play (e.g., peek-aboo), and “theory of mind” or perspective-taking abilities.

Communication Impairments

Language development in autism is often (but not always) delayed, with approximately 30% of individuals never acquiring spoken language. Language is also often atypical in children with autism, with unusual prosody and speech patterns (e.g., unusual volume, rhythm, and rate of speech), immediate and/or delayed echolalia (i.e., repetition of words and phrases, often in the same intonation as the speaker), pronoun reversal (e.g., “you want a drink” instead of “I want a drink”), and deficits in pragmatic or social use of language (e.g., difficulties in reciprocity, pedantic speech, perseveration on particular topics, tangential speech, tendency to interpret speech literally). Symbolic, or pretend, play is also impaired in autism and is associated with the development of both language and social abilities.

Restricted and Stereotyped Behaviors and Interests

These behaviors are often divided into two categories: (1) repetitive, self-stimulatory motor movements, such as hand flapping, finger flicking, toe-walking, and spinning, as well as repetitive, nonfunctional use of objects (e.g., lining up objects, spinning wheels) and (2) more elaborate preoccupations and habits, such as insisting on sameness in routine and schedule, exact ordering of objects, or compulsive-like behaviors (e.g., dressing in a specific order, eating foods in a ritualistic manner, and so on), and intense interests often involving memorization of facts (e.g., antique camera model numbers). It is important for providers to be aware that impairments in this third category are not often present at a very young age in children with autism (i.e., age 2 and younger) and that their absence at this early age does not preclude an ASD diagnosis. Further, while children with typical and delayed development may also engage in ritualistic behaviors, the number, severity, and persistence of these symptoms are distinctive and excessive in children with autism.

Epidemiology

Prevalence

Prevalence rates for the ASDs include 13 per 10,000 for autistic disorder, 2.6 per 10,000 for Asperger disorder, and 21 per 10,000 for PDD-NOS. The estimate for all ASDs (autistic disorder, Asperger disorder, and PDD-NOS collectively) is now close to 1% of all children. There has been much debate in recent years about a possible autism epidemic given the rise in rates of the disorder (now three to four times higher than in the 1970s), which now place it as more common than spina bifida, cancer, and Down syndrome. The increase in rates can be at least partly explained by the broadening definition of autism, changes in DSM nosology from 1980 to present, and the emergence of Asperger disorder as a diagnostic category. Improved identification and use of the diagnosis to qualify for state early intervention programs have also contributed to higher rates of ASD, but environmental factors, although poorly understood, cannot be overlooked.

Demographics

ASDs affect three to four males per female. Females with autism exhibit more severe symptoms, including more severe intellectual disability compared to males with autism. The gender differences found in autism may reflect a higher genetic loading, or increased number of susceptibility alleles, in families with females with autism. Indeed, a genetic study by Schellenberg found unique linkage signals distinguishing families with affected males only versus families with at least one female affected member.

Individuals of all races, ethnicities, and socioeconomic levels are affected by autism. Access to treatment varies and is impacted by racial and ethnic minority status, low education levels, and geographic location. More children with autism are found to have unmet needs for specific health care services as compared to other children with special health care needs.

Etiology and Pathogenesis

There is remarkable heterogeneity within the ASDs—in symptom presentation, course, and response to treatment. This heterogeneity presents a significant challenge to those studying the underlying etiology of these disorders. Only about 10% of cases of autism are associated with known genetic disorders, such as fragile X syndrome; the remaining 90% are idiopathic. While specific causes remain largely unknown, there is substantial evidence for a strong genetic component to autism, with heritability estimates ranging from 91% to 93%.

Genetic Factors

Twin and Family Studies

The concordance rate for monozygotic twins is about 60%; when the broader range of the disorder is included, this rate rises to about 92% for monozygotic twins and 10% for dizygotic twins. The recurrence risk rate for siblings of children with autism is approximately 2% to 8%, compared to a 0.6% general population risk. The rates of autism in second- and third-degree relatives are much lower (0.18% and 0.12%, respectively).

Broader Phenotype

A broader autism phenotype, involving qualitatively similar but milder impairments than those found in autism, has been identified in as many as 25% of siblings and 10% of parents of individuals with autism. Even second- and third-degree relatives have been shown to exhibit broader phenotype impairments. These impairments include social skills deficits, pragmatic language deficits, executive function impairments, deficits in reading comprehension, and higher rates of repetitive and obsessive-compulsive behaviors. Toth and colleagues, and others, have documented broader phenotype impairments (social and communication deficits) in siblings as early as the first 2 years of life.

Candidate Genes

Several regions of interest have been identified, including areas on chromosomes 1p, 2q, 3p, 7q, 15q, and 17q. A region on 7q is thought to be associated with speech and language deficits. Duplications of 15q11-13 are fairly common in affected individuals, occurring in up to 5% of persons with ASD. This region is of particular interest because deletions in this area have been associated with other developmental syndromes, such as Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes. Among other candidate genes in a growing list are neurexin and neuroligin genes, contactin 4, semaphorin 5A, cadherin genes, FOXP2, RAY1/ST7, IMMP2L, RELN, GABA receptor and UBE3A genes on chromosome 15q11-13, and the oxytocin receptor at 3p25-26.

Epigenetics

Epigenetic regulatory mechanisms have already been implicated in the pathogenesis of Rett syndrome and fragile X syndrome. The reelin gene (RELN) is regulated by DNA methylation, which can be modified by both gene (mutation) and environmental factors (prenatal exposures and postnatal experience). Regions on chromosomes 15q and 7q have been found to overlap with regions subject to genomic imprinting and, thus, are likely to confer risk for autism. Epigenetic studies also suggest a central role for GABAergic systems.

Environmental Risk Factors

Associated environmental risk factors that may contribute to autism include low birth weight, maternal education, delays in prenatal care, father’s age (younger was associated with risk reduction), and termination of a prior pregnancy. Whether these are liabilities of risk for autism or markers of extant genetic abnormalities remain unknown. Other environmental influences include prenatal exposure to rubella infection, valproic acid, cocaine, and thalidomide.

Two factors that have received a great deal of media attention are the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine, and the ethyl mercury-containing preservative thimerosal that was, until 2001, commonly added to vaccines. Numerous independent investigations have failed to confirm an association between the MMR vaccine or thimerosal exposure or environmental mercury and autism. Aluminum in vaccines has also been studied and does not appear to play a causal role in autism.

Neurobiology of Autism

Brain Volume

Unusual brain growth patterns in children with autism were first reported in 2001 by Courchesne and colleagues. Head circumference in infants with ASD was found to be smaller at birth than that of healthy infants. However, between 6 and 14 months of age, there was an acceleration of head growth such that mean head growth was at the 84th percentile by 6 to 14 months. Further, this increase in head circumference was associated with larger cerebral cortex volumes at 2 to 5 years. Interestingly, at 12 years and older, differences in total brain volume between individuals with autism and typically developing individuals disappear, due to a slight decrease in volume in autism as compared to the increase in volume normally seen at this age.

MRI and fMRI Findings

Frontal lobe development is disrupted in autism, perhaps explaining the deficits in working memory, executive function, and adaptive function seen in individuals with autism. There is also reduced functional connectivity within and between neocortical systems in autism, impacting problem solving, language, working memory, and social cognition. The mirror neuron system, which is active both when imitating and when merely observing others’ actions, is also impaired in autism and may contribute to the social-emotional deficits seen in autism.

Face Processing Deficits

Face processing impairments in autism are thought to be the result of fundamental impairments in the neural processing system specialized for faces (i.e., less activation of the fusiform gyrus) combined with fewer early experiences with faces due to decreased social interest and attention. Individuals with autism show abnormalities in how well they process faces, how fast they process faces, and in how they process faces (using features rather than a holistic approach). They also spend less time scanning the eye region and more time looking at mouths, body parts, and objects. Face processing impairments have also been demonstrated in parents and siblings of individuals with autism.

Comorbid Disorders and Behaviors

Intellectual Disability

Forty percent to 55% of individuals with autism also have intellectual disability or mental retardation. Deficits specific to autism include nonverbal communication, imitation, social cognition, play, and emotion recognition. Symptoms common to both autism and mental retardation include motor stereotypies, self-injurious behaviors, and sleep issues.

Seizure Disorders

The epilepsy prevalence rate in individuals with both autism and intellectual disability is 21.5%, as compared to 8% in those with autism alone. The pooled prevalence of epilepsy in females is about 34.5% versus 18.5% in males. Typical age of onset of epilepsy in autism is before 3 years of age or, more frequently, during puberty (11 to 14 years).

Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

ADHD is a common initial diagnosis in autism; as many as 31% to 55% of children with autism also meet criteria for ADHD.

Tic Disorders

Roughly 22% of children and adolescents with autism have co-occurring tic disorders, half of those presenting with Tourette syndrome and half with chronic motor tics.

Anxiety and Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder/Phobias

Symptoms of anxiety are so common in autism (both in lower and higher functioning individuals) that they are thought to be part of the disorder. Anxiety in children with ASD tends to be focused on specific things and/or related to changes in routine, novel experiences, and transitions. Over 40% of children with autism are reported to meet diagnostic criteria for a specific phobia, with the most common being needles (shots), crowds, and loud noises. Almost as many (37%) meet criteria for obsessive-compulsive disorder, with half of those exhibiting compulsions involving another person (e.g., parents need to act or respond in a specific way). Also common is the compulsive behavior to repeatedly ask or say something.

Mood Disorders

As many as 30% of individuals with HFA and Asperger disorder also have depressive symptoms. Depression in autism leads to greater withdrawal, noncompliance, and aggressive behaviors. The co-occurrence of bipolar disorder and autism is much less commonly reported in children.

Psychosis

Psychosis in children with autism is also uncommon. The intense preoccupations and circumscribed interests common in autism resemble delusions and thought disorders; therefore, care must be taken when diagnosing these disorders.

Sensory Issues

Many clinicians believe that sensory dysfunction is central to autism. Typical sensitivities include excessive negative reactions to light, sound (e.g., the sound of household appliances), or touch (e.g., certain textures of clothing, objects touching the head), high pain tolerance, and sensoryseeking behaviors (e.g., licking and biting objects, seeking deep pressure by pressing against objects or people, fascination with touching certain textures).

Self-Injurious Behaviors

Self-injurious behaviors are commonly seen both in children with autism and children with intellectual disability, and include biting, head banging, and hair pulling. Self-injurious behaviors are more often seen in younger children, children with more severe symptoms of autism, and children with more severe cognitive and adaptive delays.

Eating and Sleeping Disturbances

Aberrant eating habits are commonly reported (over 90%) by parents of children with autism and fall into three categories: food selectivity, food refusal, and disruptive behaviors at mealtimes.

Sleep difficulties are also noted, including difficulty falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakening, and waking too early in the morning.

Sleep difficulties are also noted, including difficulty falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakening, and waking too early in the morning.

Clinical Course

Early Onset

There appear to be two primary types of clinical onset in autism. With early onset, behavioral symptoms emerge within the first year of life, although these symptoms are not always obvious to parents. Symptoms as early as 8 to 12 months of age include failure to orient to name, lack of pointing and showing, decreased orienting to faces, and less frequent use of babble and words, among others. Of these behaviors, failure to respond to name is most often reported by parents in the first year and is easily assessed within the context of a well baby exam. After a few minutes of interaction, the physician should stand several feet away from (preferably behind) the child and call his or her name. Several attempts should be made with a brief pause in between. Children who do not respond to the first two attempts by turning their head and making eye contact should receive additional follow-up (see the section Assessment).

Regression

The second course of onset, occurring in approximately 30% of cases, is a period of fairly typical development followed by a loss of previously acquired skills typically occurring between 16 and 24 months of age. Losses can occur in social interest and responsiveness, communication, and adaptive skills, although a loss of language skills is almost always reported by parents. No differences in outcomes have been found between children with and without a regression.

Outcomes

Outcomes have improved with earlier diagnosis and treatment. About 50% of individuals with autism have fair to good outcomes based on occupation, friendships, and independent living. Regarding shorter-term outcomes, over 50% of children with autism followed from the age of 2 to 9 years achieved cognitive scores in the average range. The strongest predictors of positive outcomes (i.e., academic and social competence) for individuals with autism include IQ above 50, language (useful speech by the age of 5 years), adaptive functioning, and symptom severity.

Assessment

Early Screening and Diagnosis

The following section provides information on screening and diagnostic tools, as well as an evidence-based approach to assessment of ASDs. See also the American Academy of Pediatrics Clinical Report on Identification and Evaluation of Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders, listed in the Suggested Websites section at the end of this chapter.

Specific Symptoms to Assess

At birth, eye contact is present in typically developing infants and can be assessed at each well baby exam. Babies prefer to look at faces over objects. Engage the infant with talking and smiling; typically developing infants will orient to the face. By 9 months, providers can assess not only eye contact (as described above), but also social smiling, response to name, and response to social play (e.g., peek-a-boo). This assessment takes only a minute to complete. Engage the infant with talking and smiling, call the infant by name from several feet away and to the side of the infant, engage in peek-a-boo. Typically developing infants will smile, coo, look at the practitioner, turn when they hear their name, and show enjoyment during games such as peek-a-boo (by smiling and showing increased motor movements). At 12 months, most infants are making simple sounds (“ma” and “da”), using simple gestures (waving goodbye), and imitating actions (clap when you

clap). By 12 months, most infants will also point to show an object, and follow an adult’s point to an object (i.e., joint attention). Again, assessment for these skills takes only a minute or two during an office visit. Engage the infant by calling his or her name, then point to an object across the room and say “look.” Play peek-a-boo or other social game (e.g., sing a baby song) and then clap. Wave hello and goodbye to the infant. If a child should fail any of these assessments, providers should obtain additional information from the parent via a clinical interview (to assess whether failure during the office visit is perhaps due to shyness; to determine if the child is showing these behaviors at home and in other settings). Referral to a child development clinic or autism-specific clinic for a more comprehensive evaluation may be warranted. If a child is showing delays in any area, referral to a state Birth-to-Three intervention program is also warranted.

clap). By 12 months, most infants will also point to show an object, and follow an adult’s point to an object (i.e., joint attention). Again, assessment for these skills takes only a minute or two during an office visit. Engage the infant by calling his or her name, then point to an object across the room and say “look.” Play peek-a-boo or other social game (e.g., sing a baby song) and then clap. Wave hello and goodbye to the infant. If a child should fail any of these assessments, providers should obtain additional information from the parent via a clinical interview (to assess whether failure during the office visit is perhaps due to shyness; to determine if the child is showing these behaviors at home and in other settings). Referral to a child development clinic or autism-specific clinic for a more comprehensive evaluation may be warranted. If a child is showing delays in any area, referral to a state Birth-to-Three intervention program is also warranted.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree