Figure 2.1. Adult skull bones (side view), including anatomic landmarks for skull procedures. Internal axial view of the base of the skull (anterior, middle and posterior cranial fossa) with major holes of the base [1].

2.2.2 Brain (Forebrain, Cerebellum and Brainstem)

The brain begins to develop in embryonic life. On day 28, the neural development of the embryo is in the so-called “3-vesicle” stage:

- The prosencephalon (forebrain) gives rise to the telencephalon (cerebral hemispheres) and diencephalon (third ventricle, thalamus and hypothalamus).

- The mesencephalon (midbrain) gives rise to the mesencephalon itsef.

- The rhombencephalon (hindbrain) gives rise to the metencephalon (pons and cerebellum) and myelencephalon which, in turn, give rise to the bulb and part of the spinal cord. The neural tube then continues its development as the spinal cord and vertebral column.

Around day 35 of gestation, the 3-vesicle embryo progresses to the 5-vesicle stage (telencephalon, diencephalon, mesencephalon, metencephalon and myelencephalon), and at day 180 starts forming sulci through growth and myelination. The meninges, in turn, form two structures, the neural crest (arachnoid and pia mater) and the mesenchyme (dura mater). The final weight of the brain on completing growth is around 1300 g in women and 1400 g in men.

The areas of intra-cortical association continue to develop even into adulthood. Growth is set to fully develop structures of the neo-cortex such as the frontal lobes, where social learning is developed. The growth of association fibres occurs mainly through three structures: the fornix, corpus callosum and anterior commissure. The general divisions of the cerebral lobes are formed from the fissures (deeper sulci), and within each lobe there are subdivisions (gyri or convolutions) formed by less deep or smaller sulci.

The lateral or Sylvian fissure divides the frontal from the temporal lobe. It is about 7 cm long.

The central or Rolandic fissure starts inside in the middle of the hemisphere and is directed downward and forward to join the Sylvian fissure.

The sulcus callosomarginalis is inside, above the cingulate gyrus.

The calcarine fissure begins at the internal occipital pole and continues forward to the parieto-occipital sulcus.

The sulcus callosomarginalis, the Sylvian fissure, the parieto-occipital sulcus and the collateral sulcus are the only ones with 100% continuity. These, along with the Rolandic and the calcarine fissures, the pre-central and the inferior temporal sulci, are the only anatomical grooves that are generally constant and present a uniform pattern in human anatomical studies [1-3].

The frontal lobes are located between the Sylvian, the Rolandic and the sulcus callosomarginalis. The parietal lobes start from the Rolandic fissure and end in the external projection of the parieto-occipital sulcus and above the projection of the Sylvian fissure. The temporal lobes are below the Sylvian fissure and are separated from the occipital lobe by an imaginary line. They have five sulci: the superior temporal; the middle temporal; the inferior temporal; the rhinal; and the collateral.

On its basal face is the “uncus” of the hippocampus, in its anterior and posterior portions, a key structure in the development of uncal herniation due to displacement of this structure against the third cranial nerve and against the cerebral peduncle in the midbrain, thus compromising pupillary contraction (dilated pupil) and the pyramidal motor pathway (contralateral hemiparesis), peculiar of this syndrome. There is a lobe within the interior of the temporal lobe called the insular lobe or Island of Reil. It is at the bottom of the Sylvian fissure and is triangular in shape, with an anterior inferior apex and a superior base. The occipital lobes have a major sulcus (calcarine fissure) and two minor sulci: the transverse occipital and the temporal occipital [1-3].

Within the association structures are three major connections between the two hemispheres and the central fibres of association. In particular:

- Corpus callosum: about 7 to 10 cm long, located along the ventricular system, and consists of four parts: the rostrum (adjacent to the lamina terminalis); the knee linking the frontal lobes; the body joining the parietal and temporal lobes; and the splenium joining the temporal and occipital lobes.

- Anterior commissure: located behind the rostrum of the corpus callosum.

- Posterior commissure: situated at the posterior edge of the third ventricle above the aqueduct of Sylvius.

- Superior longitudinal fascicle: the longest of the association fibres, arches over the insular lobe and connects the frontal with the temporal and parietal lobes.

- Uncinate fasciculus: a large group of fibres inside the Island connecting the basal portion of the frontal lobe with the temporal lobe.

- Inferior occipitofrontal fasciculus: connects the frontal with the occipital lobe running along the side of the basal ganglia.

- Cingulum: located in the cingulate gyrus, starts from the rostrum of the corpus callosum and runs laterally in the parahippocampal gyrus.

The cerebellum is located behind the pons and the bulb. It is separated from the forebrain by the cerebellar tentorium, which is a splitting of dural tissue that separates the supratentorial from the infratentorial structures (anterior and middle fossae from the posterior fossa). It measures about 6 x 10 x 4 cm and weighs 140 g, which corresponds to 10% of brain weight. It connects to the brainstem via three branches or peduncles: the superior cerebellar or “brachium conjuntivum” (which joins the midbrain); the middle cerebellar or “brachium pontis” (which joins the pons); and the inferior cerebellar or restiform body (which joins the brainstem). Within its development, the fourth ventricle is formed just below. Functionally, the division is established through three lobes: anterior (posture and tone fibres); posterior (vestibular fibres of balance); and medium (fibres of voluntary movement) [1-4].

The brainstem consists of four structures: the diencephalon; the midbrain; the pons; and the medulla oblongata. The diencephalon corresponds to a triangular cavity. Its side wall is formed by the two thalami; the anterior side is the anterior commissure, the posterior side is the pineal gland and the posterior commissure; the base is formed by the tela chorioidea located between the two thalami, and the vertex is above the pituitary gland.

The thalamus is a paired nucleus measuring approximately 35 x 20 x 25 mm. In back of the diencephalon is the pineal gland or epiphysis located on the quadrigeminal plate, and the hypothalamus in the anterior part located on the floor of the third ventricle and limited by the optic chiasm and the lamina terminalis. It has two units: an anterior (parasympathetic activity) and a posterior (sympathetic activity) [1-4].

The midbrain begins to develop with the closing of the alar plates to form the fourth ventricle. The cells of the plates are arranged on the ventricle to form the quadrigeminal plate, and cells of the basal lamina form the tegmentum in the ventricular floor. The mantle layer forms the cerebral peduncles to connect to the thalamus and between them are the red nucleus and substantia nigra. The red nucleus, predominantly motor, is responsible for coordinating decorticate movement which is evident in patients with acute brain injury. The dorsal surface is formed by the superior and inferior quadrigeminal colliculi, connected to vision and hearing, through the fibres of the medial and lateral geniculate bodies, and the ventral surface formed by the cerebral peduncles. The medial surface has, in the inter-peduncular sulcus, the emergence of the third cranial nerve. The lower edge is attached to the pons and on the lateral face are the pontomesencephalic sulci [1-4].

The pons originates within the pontic flexure in the rhomboid fossa of the fourth ventricle. In the basal lamina are the motor nuclei of cranial nerves VI and VII. In the alar lamina of this region are several nuclei, such as the vestibular nuclei, which coordinate a movement called “decerebration” in patients with impaired higher motor functions, the cochlear nuclei, the inferior olivary nuclei, the solitary fascicle, and the descending nucleus of the V pair. It is located under the cerebral peduncles and in front of the cerebellum. On its anterior face is the basilar artery and the apparent origin of the V pair (trigeminal). On the lateral face are the middle cerebellar peduncles that are directed towards the cerebellum. On its lower face is the pontobulbar sulcus which separates it from the medulla oblongata [1-4].

The medulla oblongata originates from the myelencephalon. The alar lamina originates nuclei for the X and XII cranial nerves. It continues in the spinal cord and separates from it by the decussation of the pyramids, an area where the fibres from the pyramidal cells in the motor cortex cross over to the contralateral side. Its anterior portion is closely related to the odontoid process or apophysis of C2 (for this reason, a high cervical injury with impaction of the odontoid directly impairs the medullary respiratory centres). On its front face are the preolivary sulci, the apparent origin of the XII cranial nerves and the bulbar pyramids. On its posterior face are the posterior lateral sulci, an area of apparent origin of the IX, X and XI cranial nerves. There are also the colliculi of gracilis fasciculus and cuneatus fasciculus (posterior cords of the spinal cord). There is also the inferior cerebellar peduncle which connects it to the cerebellum, and part of the floor of the fourth ventricle, with the acoustic striae and hypoglossal and vagal trigones. On the lateral face is the olive, the seat of the inferior olivary nuclei, and the pontomedullary sulcus, the apparent origin of the VI, VII and VIII nerve pairs [1-4].

2.2.3 Brain (Arterial and Venous System)

Understanding the arterial and venous systems is fundamental for appreciating many aspects of the pathophysiology, monitoring, and treatment of acute brain injury. Cerebrovascular emergency, for example, requires quickly correlating the anatomical aspect and the clinical location, and this must be understood by all staff involved in caring for critically ill patients. Hereafter, we will describe in detail the nomenclature and location of the major cerebral vessels, both arterial and venous.

The internal carotid artery (ICA) originates at the bifurcation of the common carotid, usually at the level of the C1-C2 disc. It has four parts: C1 (cervical) runs from the bifurcation of the common carotid to the external orifice of the carotid canal of the skull; C2 (petrous) runs from the cranial carotid canal entrance to the entrance of the cavernous sinus inside the skull; C3 (cavernous) runs from the entrance to the exit of the cavernous sinus; and C4 (supraclinoid) runs from the exit of the cavernous sinus (entry into the subarachnoid space) to its division into the middle and anterior cerebral arteries.

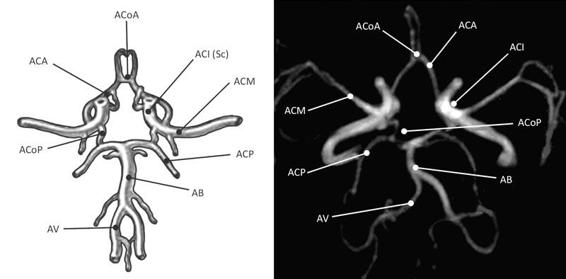

The supraclinoid portion consists of three segments: the lower one is the ophthalmic segment (where the ophthalmic artery arises); the middle one is the communicating segment (where the posterior communicating artery arises); and the upper one is the choroidal segment (where the choroidal artery arises). The ophthalmic segment has four to seven perforating branches directed to the pituitary stalk (superior pituitary), the optic nerve, and the chiasm. The ophthalmic artery is located below the chiasm and has a very short intracranial segment of about 3 mm before it enters the orbit. The communicating segment has some inconstant perforating arteries directed to the chiasm and the optic nerve. The posterior communicating artery (PCoA) is very important because it forms the lateral wall of the circle of Willis (Figure 2.2) connecting the carotid with the posterior cerebral artery, which comes from the infratentorial circulation and is a key element in collateral circulation in supratentorial cerebral ischemia [1,7,8,9].

Figure 2.2. Diagram and magnetic resonance angiography image of the arteries forming the Circle of Willis. From [1].

ACA = anterior cerebral artery; ACoA = anterior communicating artery; BA = basilar artery; ICA (Sc) = supraclinoid internal carotid artery; MCA = middle cerebral artery; PCA = posterior cerebral artery; PCoA = posterior communicating artery; VA = vertebral artery.

The so-called “foetal configuration of the posterior communicating artery” occurs when the artery gives rise to the posterior cerebral artery (PCoA) rather than originate from the basilar system. This pattern t can occur in adults and is called such because it is normal in the cerebral circulation of the foetus. This segment can have about eight perforating branches directed to the third ventricle, thalamus, hypothalamus, internal capsule, pituitary stalk, and chiasm, among others. The choroidal segment has about four perforating arteries directed to the anterior perforated substance, the optic tract and the uncus. The anterior choroidal artery (AChA) provides irrigation to the choroid plexus within the ventricle temporal horn [1,12,13].

The middle cerebral artery (MCA) has an initial diameter of about 4 mm. It originates at the end of the Sylvian fissure on the inner surface of the temporal, lateral to the optic chiasm; at the level of the fissure it divides to direct to the temporal and parietal. It has four parts: M1 (sphenoidal) from the bifurcation of the ICA to the insular region within the Sylvian fissure; M2 (insular) is the segment within the Island of Reil; M3 (opercular) runs from the peri-insular region to the outside of the Sylvian fissure; and the M4 (cortical) goes from the exit through the Sylvian fissure until complete distribution on the outer face of the lobes, where it irrigates the vast majority of functional cortical areas. In 80% of cases, in the pre-bifurcation area of M1, the lenticulostriate arteries originate: they are important in hemorrhagic cerebrovascular events because they cause hypertensive hematomas at the basal ganglia level. There are approximately ten in each hemisphere [1,3,12].

The anterior cerebral artery (ACA) is smaller than the MCA. It is anterior and medial to the optic nerve. It projects forward between the two hemispheres, parallel to its contralateral, and they join through the anterior communicating artery (ACoA). It has five parts: the A1 portion (precommunicating) from the origin to the anterior communicating artery; A2 (infracallosal) lies below the rostrum of the corpus callosum; A3 (precallosal) courses past the knee of the corpus callosum; A4 (supracallosal) runs above the corpus callosum; and A5 (postcallosal) located behind the splenium of the corpus callosum. The ACoA is the anterior portion of circle of Willis and is generally no longer than 3 mm. A1 has a branch often called the “recurrent artery of Heubner” which supplies the basal ganglia and internal capsule. This branch may be injured by searching for the ACoA during aneurysm surgery.

The pericallosal artery begins in the ACoA and around the corpus callosum. It includes the portions from A2 to A5. It has a branch called the callosomarginal artery that ascends and continues back through the cingulate sulcus. Usually it comes out of the A3 portion. The ACA also has cortical branches in the frontopolar, frontal and parietal regions [1-3].

The vertebral arteries (VA) originate from the subclavian arteries and enter the structure of the cervical spine through the vertebral foramen from C6, ascending to C2, where they curve medially to settle at the transverse process of C1 and then cross over the posterior arch. They enter the dura at the foramen magnum, giving rise to the posterior spinal artery and the posterior meningeal artery. The intradural segment of the VA is divided into two subsegments, the lateral and the anterior medullary, which then join with the contralateral to form the basilar artery. An additional main branch of the VA is the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA) which supplies the medulla oblongata, the bottom of the fourth ventricle, the cerebellar tonsils, and the lower side of the cerebellum [1-4].

The basilar artery (BA) has its origin at the junction of the two VAs at the pyramidal tract of the medulla oblongata, and it ascends on the anterior surface of the pons in the so-called basilar sulcus. Its main branch is the anterior inferior cerebellar artery (AICA) which usually emerges in the lower third of the BA. It turns back and generally surrounds the pons, irrigating the lower two thirds of the pons and the upper third of the medulla oblongata. In the upper third of the basilar artery, before its bifurcation into the posterior cerebral arteries, the superior cerebellar artery emerges (SCA), which turns back on the upper level of the pons at the pontomesencephalic sulcus. This artery supplies the quadrigeminal lamina and the cerebral peduncles of the midbrain [7-9].

The posterior cerebral artery (PCA) emerges from the bifurcation of the basilar and meets the PCoA in the lateral region of the interpeduncular cistern. It goes through the crural and ambient cisterns in the so-called tentorial incisura (free space of the tentorium which surrounds the midbrain and connects the supratentorial and infratentorial spaces). It supplies the occipital region, thalamus, midbrain, and choroid plexus.

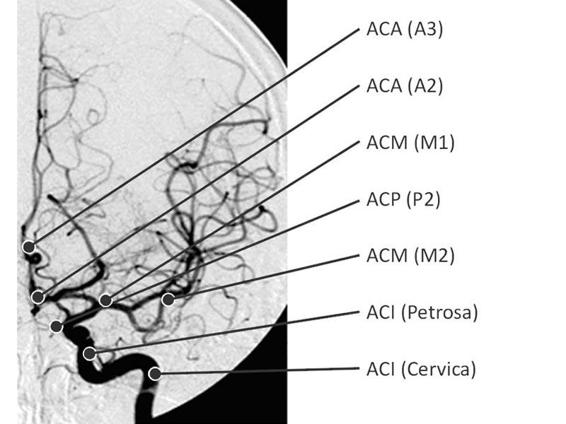

The P1 segment (pre-communicating) goes from the basilar bifurcation to the junction with the PcoA, is about 7 mm long, gives rise to the thalamoperforating, choroidal, quadrigeminal branches, and branches to the cerebral peduncles. The P2 segment (cisternal) is about 25 mm long, runs from the junction with the PCoA to the rear edge of the midbrain, and is subdivided into the P2A segment (crural) and the P2P segment (ambient). These segments give rise to the hippocampal, temporal, peduncular, choroidal, and thalamus branches. The P3 segment (quadrigeminal) is 20 mm long and runs from the posterior region of the midbrain to the calcarine fissure, crossing through the quadrigeminal cistern. It is divided into two terminal branches, the calcarine and parieto-occipital branches. The final segment, P4 (cortical), begins in the calcarine fissure on the inner surface of the occipital and runs in the occipital cortical region, giving rise to branches directed to the temporal and occipital regions [7-9]. Arterial relations are especially important in the interpretation of angiographic images in emergency situations, where it is essential to detect areas of vascular injury and collateral circulation (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3. Conventional angiography and interpretation scheme. From [1].

ACA (A2-A3) = anterior cerebral artery, A2 and A3 portions; ACP (P2) = posterior cerebral artery P2 portion; ICA = internal carotid artery; MCA (M1-M2) = middle cerebral artery, M1 and M2 portions.

The cerebral venous system comprises the surface segment (veins of the skin or scalp and muscle), the intermediate segment (veins of diploë and dura mater), and the deep segment (the cerebral veins). The surface segment generally has the same distribution as the arteries. The most important are the so-called emissary veins that connect the extracranial with intracranial drainage. In severe intracranial hypertension, especially in children, they are engorged at the frontal and temporal levels. They are located in the scalp and drain into the diploic veins which subsequently drain into the dural sinuses. In the intermediate segment are the diploic veins (venous lakes located within two cranial cortices), which are important because of the risk of air embolism in open fractures. Bleeding is easily controlled by filling the space between the two bony plates with hemostatic material. They are a frequent source of bleeding in depressed fractures. This segment also contains the meningeal arteries located between the skull and the dura. They run parallel to the arteries. They are also in the dural folds (e.g., the falx and the tentorium). The most frequent are the tentorial veins, which are a frequent source of bleeding in posterior fossa interventions [5,6,13].

The dural venous sinuses are intermediate and are grouped as follows: the postero-superior group comprises the superior and inferior sagittal, straight, lateral (transverse), sigmoid, tentorial and occipital sinuses; the antero-inferior group comprises the cavernous, sphenoparietal, intercavernous, superior petrosal and basilar sinuses.

The superior longitudinal sinus (superior sagittal sinus) spans the midline and runs from the frontal pole to the occipital prominence, where the confluence of sinuses is called “torcular Herophili”. It forms spaces called venous lacunae, where the meningeal veins converge and are a source of active bleeding in fractures above the midline. These lacunae have a triangular shape and contain the arachnoid granulations. The inferior sagittal sinus (inferior longitudinal sinus) starts at the lower edge of the falx cerebri (at the level of the crista galli), extends above the corpus callosum, and turns back to drain into the straight sinus. It mainly includes the draining of the pericallosal veins. The straight sinus originates at the splenium of the corpus callosum at the confluence of the inferior sagittal sinus and the vein of Galen. It continues posteroinferiorly in the dural junction of the falx and tentorium to come together usually in the left transverse sinus. The transverse sinuses originate in the torcular and run from the occipital protuberance, parallel to the outer tentorial edge; at the level of the crest of the petrous pyramid, they converge with the superior petrosal sinus to form the sigmoid sinuses. The right one is generally larger and receives drainage from the superior sagittal sinus, while the left one is smaller and receives drainage from the straight sinus. This factor should be taken into account when monitoring the jugular vein, as it originates from the sigmoid sinus drainage; therefore, the right jugular reflects more the cortical venous drainage and the left one the subcortical or deep venous drainage [5,6,13].

The sigmoid sinuses are the continuation of the confluence of the transverse sinus and the superior petrosal sinus. They extend along the bottom edge of the petrosal bone; at the confluence with the inferior petrosal sinus, they enter the jugular foramen to form the internal jugular vein, where jugular venous bulb oxygen saturation is measured. The occipital sinuses originate from the transverse sinus, run parallel to the occipital, and drain into the sigmoid sinuses. The tentorial sinuses are not always present. There are two of them, with one usually located medially and the other one laterally. They are formed by the convergence of the tentorial, cerebellar, and occipital cortical veins. They have several drainage patterns. The cavernous sinuses are located on the sides of the sella turcica and communicate with each other through the anterior and posterior inter-cavernous sinuses located between the diaphragm sellae and the dura [10,11]. Recognizing them is important because they host the third portion of the internal carotid artery and cranial nerves III, IV, VI and the v1 and v2 branches of the V cranial nerve. The sphenoparietal sinuses accompany the anterior portion of the middle meningeal artery. They run through the lesser wing of the sphenoid bone and reach the cavernous sinus [10,11]. The superior petrosal sinuses pass along the tentorium and the edge of the petrosal bone, communicating medially with the cavernous sinus and laterally with the confluence of the transverse sinus and sigmoid sinus. The basilar sinus is a venous network located on the clivus. It communicates with the cavernous sinus and allows communication between the two groups of venous sinuses, upper and lower [5,6,12,13].

The deep venous segment is subdivided into the superficial and the deep venous system. The superficial system is basically related to the cortical veins that drain mostly into the superior sagittal sinus. Within this group are the frontal, parietal (ascending and descending), temporal (ascending and descending) and occipital (lateral and medial) veins. Within this group of veins, especially at the temporal and parietal levels, attention is called to the superior and inferior “anastomotic veins”:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree