Basic Aspects of Sleep-Wake Disorders

Gregory Stores

Introduction

A sound working knowledge of the diagnosis, significance, and treatment of sleep disorders is essential in all branches of clinical psychiatry. Unfortunately, however, psychiatrists and psychologists share with other specialties and disciplines an apparently universal neglect of sleep and its disorders in their training. Surveys in the United States and Europe point to the consistently meagre coverage of these topics in their courses at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

The following account is an introductory overview of normal sleep, the effects of sleep disturbance, sleep disorders and the risk of failure to recognize them in psychiatric practice, assessment of sleep disturbance, and the various forms of treatment that are available. The aim is to provide a background for the other chapters in this section.

The close links between the field of sleep disorders and psychiatry which make it essential that psychiatrists are familiar with the field are as follows:

Sleep disturbance is an almost invariable feature and complication of psychiatric disorders from childhood to old age, with the risk of further reducing the individual’s capacity to cope with their difficulties (see Table 4.14.1.3 for further details).

Sleep disturbance can presage psychiatric disorder.

Some psychotropic medications produce significant sleep disturbance.

Of importance to liason psychiatry is the fact that many general medical or paediatric disorders disturb sleep sufficiently to contribute to psychological or psychiatric problems.

Because of lack of familiarity with sleep disorders and their various manifestations, such disorders may well be misinterpreted as primary psychiatric disorders (or, indeed, other clinical conditions) with the result that effective treatments for the sleep disorder are unwittingly withheld (see later).

Some of these points will be amplified in later sections of this chapter.

Basic features of normal sleep

The scientific study of sleep and its disorders is largely confined to the last several decades. Essentially interdisciplinary advances have displaced earlier speculative accounts including those in psychiatry concerning the significance of dreams, for example. They are well described in recent textbooks of sleep disorders medicine (see recommended sources). Only general points are mentioned here, with special reference to psychiatry where possible.

The nature of sleep

Sleep has characteristic physiological features which distinguish it from other states of relative inactivity. Two distinct sleep states have been defined, that is non-rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep. The onset of sleep is not simply the shutdown of wakefulness but also the switching between wakefulness, NREM and REM sleep involve complicated active neurochemical mechanisms in different parts of the brain.

The functions of sleep

Debate continues about the various theories concerning sleep, each of which has emphasized physical and psychological restoration and recovery, energy conservation, memory consolidation, discharge of emotions, brain growth and various other biological functions including somatic growth and repair, and maintenance of immune

systems. No one theory accounts for all the complexities of sleep and it seems likely that sleep serves multiple purposes.

systems. No one theory accounts for all the complexities of sleep and it seems likely that sleep serves multiple purposes.

From the practical point of view, the most obvious observation is that both physical and psychological impairment follows persistent sleep disturbance. Animals totally deprived of sleep for a long periods die with loss of temperature regulation and multiple system failure. As described later, the adverse effects of chronic sleep loss (considered to be common in modern society) on mood, behaviour, and cognitive function can be substantial, with various consequences for personal, social, occupational, educational, and family functioning.

Sleep stages

Conventionally, standard criteria are used to identify different sleep stages according to their characteristic physiological features especially in the electroencephalogram (EEG), electro-oculogram (EOG), and electromyogram (EMG).

NREM sleep is divided into four stages of increasing depth. Stage I occurs at sleep onset or following arousal from another stage of sleep. This stage represents 4-16 per cent of the main sleep period. Stage II contains more slow EEG activity but is still relatively light sleep. It accounts for 45-55 per cent of overnight sleep. Stage III (4-6 per cent of total sleep time) contains yet more slow EEG activity. Stage IV is characterized by the slowest activity and constitutes 12-15 per cent of sleep. The combination of stages III and IV is called slow wave sleep (SWS) or delta sleep and is considered to be the deepest form of sleep from which awakening is particularly difficult. The arousal disorders such as sleepwalking arise from SWS.

REM sleep is physiologically very different. Brain metabolism is highest in this stage of sleep. Spontaneous rapid eye movements are seen and the skeletal musculature is effectively paralysed. Heart rate, blood pressure, and respiration are all variable, body temperature regulation ceases temporarily, and penile and clitoral tumescence occurs. REM sleep usually takes up 20-25 per cent of total sleep time. Most dreams, including nightmares, occur in REM sleep.

Sleep architecture

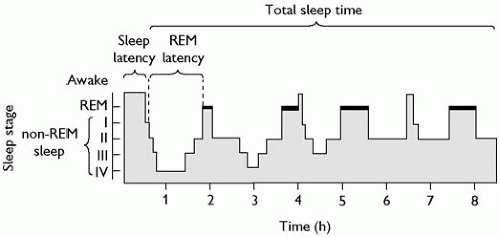

NREM and REM sleep alternate cyclically throughout the night starting with NREM sleep lasting about 80 min followed by about 10 min of REM sleep. This 90 min sleep cycle is repeated three to six times each night. Each REM period typically ends with a brief arousal or transition into light NREM sleep.

In successive cycles the amount of NREM sleep decreases and the amount of REM sleep increases. SWS is usually confined to the first two sleep cycles. The diagrammatic representation of overnight sleep is known as a hypnogram, a simplified form of which is shown in Fig. 4.14.1.1.

In addition to this conventional sleep staging, there has been increasing interest in the microstructural fragmentation of sleep by frequent, brief arousals (seen mainly in the EEG) lasting a matter of seconds without obvious clinical accompaniments. This subtle type of sleep disruption, overlooked by conventional sleep staging, is increasingly associated with impairment of daytime performance, mood, and behaviour.

Circadian sleep-wake rhythms

The timing of sleep (but not its amount) is regulated by a circadian ‘clock’ in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The intrinsic circadian sleep-wake rhythm is close to 24 h in human adults. Other species are different, an extreme example being dolphins and some other creatures which shut down one cerebral hemisphere at a time (‘unihemispheric sleep’), allowing them to be constantly alert. From an early age the individual sleep-wake rhythm has to synchronize with the 24-h day-night rhythm. The main zeitgeber by which this is achieved (‘entrainment’) is sunlight but social cues, such as mealtimes and social activities, are also important.

The SCN also controls other biological rhythms including body temperature and cortisol production with which the sleep-wake rhythm is normally synchronized. In contrast, growth hormone is locked to the sleep-wake cycle and is released with the onset of SWS, whatever its timing.

Melatonin is related to the light-dark cycle rather than the sleep-wake cycle. It is secreted by the pineal gland during darkness and suppressed by exposure to bright light (‘the hormone of darkness’). It influences circadian rhythms via the SCN pacemaker which in turn, regulates melatonin secretion by relaying light information to the pineal gland. The widespread popularity of melatonin as a sleep-promoting agent is not justified by what little is known about its action and clinical effectiveness.

Changes with age

Changes in basic aspects of sleep are prominent from birth to old age, although individual differences are seen at all ages. Changes of clinical significance include the following:

Total sleep time decreases with age. Average daily values are as follows: newborns 6-18 h; young children 10 h; adolescents 9 h (although often they obtain significantly less than this); adults 7.5-8 h, including possibly the same in elderly people. The total amount of sleep includes daytime napping in children up to the age of about 3 years.

SWS is particularly prominent in prepubertal children who sleep very soundly. Its decline begins in early adolescence and continues throughout childhood.

The proportion of REM sleep declines from 50 per cent or more of total sleep time in the newborn (more than this in premature babies) to 20-25 per cent by 2 years. This figure remains fairly constant throughout the rest of life. The high level of REM sleep in very early life suggests a role in cerebral maturation but the reason for its persistence throughout life is unclear. Memory processing appears to depend on sleep. However, people deprived

of REM sleep, experimentally or pathologically, can be relatively unaffected either emotionally or cognitively. Deep sleep decreases in the elderly.

NREM-REM sleep cycles occur at intervals of 50-60 min in infants who often enter REM at the start of their sleep period. This interval between sleep cycles remains until adolescence when the periodicity changes to 90-100 min, which persists into adult life. The amounts of NREM and REM in each sleep cycle is about equal in early infancy. Afterwards, NREM sleep (especially SWS) predominates in the earlier cycles and REM sleep in the later cycles.

Continuity of sleep is greatest in pre-pubertal children (as mentioned previously) and least at the extremes of age. Infants are easily awakened and so are the elderly who also wake spontaneously more often. Fragmentation of sleep by brief arousals, or very brief awakenings, is particularly common in old age.

Circadian sleep-wake rhythms change considerably in early development. Full-term neomates show 3-4-h sleep-wake cycles. Sleep periods have largely shifted to the night and wakefulness to daytime by 12 months, except for napping which gradually diminishes and has usually stopped by about 3 years of age. However, a physiological tendency towards an afternoon nap remains throughout the rest of the life. Although repeated brief waking at night is more common in infancy and early childhood than later, it remains a normal occurrence throughout life, increasing in frequency again in old age. The clinical problem arises when there is difficulty returning to sleep after such awakenings.

Psychological effects of sleep disturbance

There is extensive clinical and experimental evidence that sustained sleep disturbance can have serious adverse psychological effects.(1,2) The term sleep disturbance covers the following:

Loss of sleep (i.e. shortened duration).

Impaired quality of sleep (repeated disruption of sleep architecture).

Inappropriate timing of the sleep period in relation to day-night rhythms (as in the various circadian sleep rhythm disorders such as jet lag, shift work, or the more frequently encountered forms seen in clinical practice, as discussed later).

Experimental studies of total sleep loss demonstrate a progressive deterioration in cognitive function, mood, and behaviour related to length of sleep loss. However, inter- and also intra-individual differences in susceptibility are seen, reflecting such factors as motivation, personality, and usual sleep requirements. Task characteristics (e.g. brief or prolonged and monotonous tasks), timing of the task in relation to the circadian sleep-wake rhythm, and physical environmental factors such as noise and other distracting stimuli, are also important.

Variations for similar reasons are important in partial sleep deprivation experiments which (like those concerning fragmentation of sleep) are much closer to real-life sleep disturbance caused by social activities, job demands, and other aspects of modern lifestyle. These studies raise the issues of how much sleep is needed for optimal daytime functioning and whether these requirements are not being met. It has been argued that there is ‘national sleep debt’ in the United States and other western countries, and that by sleeping longer than they do habitually, many people would increase their performance and improve their well-being during the day.

The usual subjective effects of sleep disturbance are irritability, fatigue, poor concentration, and depression. More dramatic effects are described with prolonged and severe sleep disturbance, such as disorientation, illusions, hallucinations, persecutory ideas, and inappropriate behaviour with impaired awareness (‘automatic behaviour’) caused by frequent microsleeps. Psychometric studies have shown that sleep disturbance can produce a range of cognitive impairments, again depending on its duration and individual susceptibility. Sustained attention (vigilance) is particularly vulnerable and possibility abstract thinking and divergent intelligence or creativity.

The experimental findings are in keeping with the results from studies of various occupational groups including junior hospital doctors and drivers of various types of vehicle, in which reduced performance or accidents are associated with sleep disturbance. The common and increasing practice of night-shift work (as part of the ‘24 h society’) is contrary to the fundamental biorhythm of sleeping at night and being awake during the day, and is often accompanied by a reduction in total sleep time and poor quality sleep. It is not surprising that working shifts commonly results in loss of well-being, physical complaints, and impaired productivity and safety, as well as physical disorders. Similarly, the distribution over the 24 h period of road accidents (especially those not involving other vehicles) and other mishaps at work, correspond to that of the levels of sleep tendency assessed objectively. Even industrial and engineering disasters have been attributed to sleep loss and impaired performance on the part of key personnel.

Additional evidence that sleep disturbance affects daytime function comes from neuropsychological studies of certain sleep disorders. Impaired performance on prolonged and complex tasks of subjects with narcolepsy has been shown to be secondary to the effects of their daytime sleepiness rather than an intrinsic neurological deficit. In the many adult patients with obstructive sleep apnoea, attention memory impairment (like depression and irritability commonly reported by these patients) are also largely attributable to daytime sleepiness. There is some evidence that deficits in more complicated ‘executive functions’ (formulating goals, planning, and carrying out plans effectively) are not necessarily reversed when their sleepiness is relieved by treatment. This might be the result of irreversible anoxic brain changes in the later stages of the condition. Clearly, early detection and treatment of this condition is essential to prevent this happening.

When return to normal sleep is possible, recovery from short periods of sleep disturbance occurs after much less sleep than that originally lost, for example, after one night’s sleep following sleep loss over several days and nights. Reversal of the effects of long sleep disturbance in real-life is likely to be complicated, for example by emotional consequences of the disturbance.

Many of the above observations about the psychological effects of sleep disturbance (and their reversibility) have been made on young adult subjects or patients. The area is largely unexplored in other age groups but there is no reason why the general principle should not apply to children and the elderly including demented patients in whom sleep disturbance is particularly prominent.

Another group on whom further research is particularly required are people with learning disabilities (intellectual disability).

The available literature provides good reason to believe that the sleep disorders, especially in the more severely disabled groups, not only affects the majority but also are unusually severe and long-lasting because of lack of appropriate advice and treatment. The sleep disturbance is a problem in its own right and is often associated with various cognitive and behavioural abnormalities which might, at least partly, be the consequence of the sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbance in the duration or the quality of sleep may be one of the few ways of improving to some extent the psychological well-being of people with learning disabilities or dementia (and that of their carers) whose basic condition itself cannot be improved. In the case of the learning disabled, contrary to the common supposition by both professionals and relatives, success can usually be achieved (even in severe and long-standing problems), given an accurate diagnosis of the type of sleep disorder which may be predominantly behavioural or physical in type depending on the cause of the learning disability.

The available literature provides good reason to believe that the sleep disorders, especially in the more severely disabled groups, not only affects the majority but also are unusually severe and long-lasting because of lack of appropriate advice and treatment. The sleep disturbance is a problem in its own right and is often associated with various cognitive and behavioural abnormalities which might, at least partly, be the consequence of the sleep disturbance. Sleep disturbance in the duration or the quality of sleep may be one of the few ways of improving to some extent the psychological well-being of people with learning disabilities or dementia (and that of their carers) whose basic condition itself cannot be improved. In the case of the learning disabled, contrary to the common supposition by both professionals and relatives, success can usually be achieved (even in severe and long-standing problems), given an accurate diagnosis of the type of sleep disorder which may be predominantly behavioural or physical in type depending on the cause of the learning disability.

Sleep disturbance in the aetiology of psychiatric illness

Various ‘psychotic’ and other abnormal psychological phenomena were mentioned earlier resulting from prolonged and severe sleep disturbance, but these are reversed when normal sleep is restored. It remains an open question how often sleep disturbance is a primary cause of psychiatric illness. Evidence is patchy, tentative, and still in need of clarification.

Over a wide age range, patients with a prior history of insomnia have been found consistently to be at significantly increased risk for severe depression. This could be interpreted in different ways including that sleep disturbance and the depression have a common underlying pathology, or that the sleep problems are an early sign of depression.

A less fundamental role (but again implying preventative possibilities) is the suggestion that sleep deprivation late in pregnancy and in labour and childbirth at night might trigger post-natal depression.

Abnormal circadian sleep-wake rhythms have been implicated in various depressive disorders including seasonal affective disorder (SAD). Light therapy has been used to correct the abnormality and relieve the depression and other symptoms.

Disordered REM sleep mechanisms have (questionably) been considered as fundamental in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms.

Some forms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children are attributed to persistent sleep disturbance.

In a proportion of patients with schizophrenia, narcolepsy has been reported as the cause of their psychotic symptoms.

Disorders of sleep

Sleep complaints

The starting point for the clinician is the patient’s sleep complaint. They are of three basic types:

Not enough sleep, or unrefreshing sleep (insomnia).

Sleeping too much (excessive daytime sleepiness or hypersomnia).

Disturbed episodes during or otherwise related to sleep (parasomnias).

The detailed accounts later in this section are organized in relation to these main types of sleep complaint: insomnias (Chapter 4.14.2); excessive daytime sleepiness (Chapter 4.14.3); and parasomnias (Chapter 4.14.4). Sleep problems in childhood and adolescence are discussed in Chapter 9.2.9.

Whatever the clinical setting in which sleep complaints are investigated, the essential aim is to identify the specific sleep disorder from the many other conditions that can give rise to such complaints. Some sleep disorders may cause more than one type of complaint, and a patient may have more than one sleep disorder. The question arises how best to classify the many sleep disorders that have been described.

International classification of sleep disorders—second edition 2005 (ICSD-2)

This system, derived from wide international consultation, is the latest attempt to organize rationally the many ways in which sleep can be disturbed. ICSD-2 replaced the ICSD-Revised scheme outlined in the first edition of this textbook. More than 90 different sleep disorders are grouped as shown in Table 4.14.1.1. The grouping reflects the fact that knowledge about individual sleep disorders is very varied. The basic pathophysiology of some is quite well documented; in others little is known beyond their manifestations, and even they are subject to change as clinical observations improve. As a result, the ICSD-2 groupings are a mixture of those based on a common complaint (e.g. insomnia or hypersomnia), others on presumed aetiology (circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders), and yet others are grouped according to the organ system from which the problems arise (such as sleep-related breathing disorders). Two additional groups in the system reflect current uncertainty about their status as disorders, or about their true nature.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree