All data are from randomized controlled trials of behavioral treatment published from 1974 to 2002 in select journals. All values, except for number of studies, are weighted means; thus, studies with larger sample sizes had a greater impact on mean values than did studies with smaller sample sizes. Table reprinted from ref. (2), which was adapted and updated from ref. (133).

These results are disappointing for most patients. However, several novel interventions have facilitated greater long-term success, such as those that used a model of continued care after initial weight loss. Recently published data from the Look AHEAD study found that after four years of continued treatment, participants maintained a weight loss of 4.7% of initial weight (7). Research, such as that from the Diabetes Prevention Program, also has demonstrated that relatively modest weight losses produce meaningful health benefits (8). In that study, 3,200 overweight or obese participants with impaired glucose tolerance were enrolled. Participants who received behavioral treatment achieved a weight loss of, on average, 7 kg at the end of one year, and they regained approximately one-third of their weight in the 2–3 years after that. Even in the context of weight regain, these participants reduced their risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 58% compared to participants treated with placebo.

Although most studies find that the size of sustained weight losses is small, there is a subgroup of participants who maintain much larger weight losses. In general, about 20% of participants maintain a weight loss of at least 10% one year after treatment ends (9). Research is being conducted to learn about individual differences that are associated with these remarkable cases of successful long-term weight control. The final section of this chapter provides more information on the important topic of weight loss maintenance.

Principles and Structure of Behavioral Treatment

The first application of behavioral principles to the treatment of obesity, described in 1967, was designed to target maladaptive eating behaviors which were believed to be the primary cause of obesity (10). Today, the influence of genetic and metabolic factors on body weight is well known (see Chapter 5). These biological factors predispose certain individuals to obesity, particularly in combination with environmental influences that encourage overconsumption of highly palatable, high-calorie foods and discourage physical activity (see Chapter 6) (11). Modern behavior therapy recognizes these influences on body weight while maintaining that modifications of eating and activity behaviors can help obese individuals achieve a healthier weight. Therefore, behavioral treatment applies principles of learning theories, such as classical conditioning and operant conditioning, to the regulation of body weight in order to help obese individuals make lifelong changes to their eating and activity habits.

Principles of Behavioral Treatment

Classical conditioning is a form of associative learning in which two stimuli become linked together if they are paired repeatedly. The association becomes stronger the more frequently they are paired until the presence of one stimulus automatically triggers the other. For example, a person who frequently eats while watching television might eventually experience an urge to eat whenever she turns on the television. A goal of behavior therapy is to identify and extinguish these associations by “unpairing” them. Restricting eating to certain places (e.g., the kitchen table) is often recommended in order to eliminate such an association between watching television and eating.

Behavior therapy uses principles of operant conditioning to promote behavior change by manipulating the consequences of eating and activity. Behaviors that are rewarded (i.e., reinforced) are more likely to be repeated. A participant who loses weight following a week of eating in accordance with his calorie goal will be more likely to continue to adhere to his calorie goal in the future. In this instance, weight loss is the reward that reinforces the desired behavior. On the other hand, behaviors that are followed by negative consequences are less likely to be repeated. For example, an individual who increases her activity level by 200 minutes in one week may feel exhausted and fatigued. As a result, she may feel discouraged from continuing her exercise program. If she began with a more modest exercise regimen (e.g., 10 minutes of exercise, 5 days per week) and gradually increased her activity level, she would be less likely to experience negative consequences of her behavior.

As described in the following section, each treatment session begins with a private weigh-in. The weigh-in is designed, in part, to provide feedback about the consequences of behavior. Participants learn quickly that their weight change reflects their adherence to their eating and activity goals. Since weight loss (the reward) usually slows over time, other strategies are used to reward positive behavior change. For example, behavior therapists provide praise (a form of reward) to participants for weight loss and help them schedule rewards for desired behaviors (e.g., purchasing a new book or DVD, if the participant meets her activity goal for the week). It is important that the reward is received only if the participant successfully achieves her goal. The reward will not be motivating if its receipt is not contingent on this success.

A challenge in the treatment of obesity is that the reinforcing value of successful weight loss is not always immediately apparent, whereas behaviors that hinder weight control efforts (e.g., consuming high-calorie foods, engaging in sedentary activity) can be rewarding in the short term (12). An important goal of behavior therapy is to help patients increase the likelihood of immediate reinforcement for engaging in healthy behaviors (e.g., providing a feeling of success after adhering to a meal plan for the week). Teaching patients to focus on the outcomes of their behaviors may be beneficial for long-term weight control. In a pilot study, Sbrocco and colleagues (13) randomized overweight individuals to a traditional behavioral weight loss program or a “behavioral choice” treatment in which participants were taught to recognize the consequences of their food and activity choices (e.g., feeling guilty after eating a high-calorie food) and modify their thinking or behavior to maximize positive outcomes. Although there were no differences between groups in weight loss at the end of treatment, participants in the behavioral choice treatment continued to lose weight following treatment whereas those in the traditional behavioral program began to regain weight. As a result, participants in the behavioral choice treatment had significantly better weight loss maintenance 6 and 12 months post-treatment.

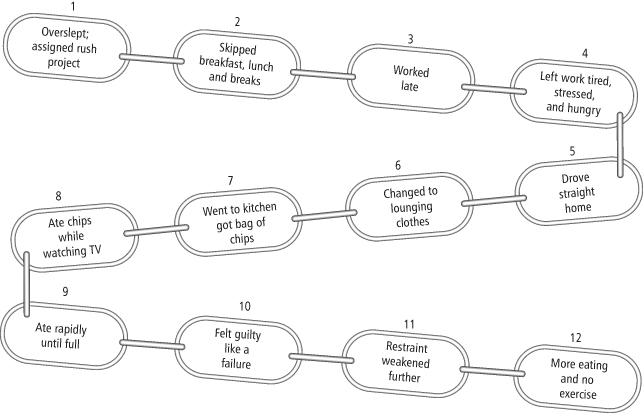

Functional analysis, the examination of antecedent events and consequences of problem behaviors, is another tool used in behavioral treatment. Functional analysis helps identify events (e.g., items, places, people) associated with unhealthy eating and activity behaviors. Such analysis helps participants recognize how problem behaviors are often triggered through a series of events that are linked together in a chain. An examination of the links in the behavioral chain can help identify opportunities for intervention (see Figure 15-1).

Figure 15-1 Sample Behavior Chain

A behavior chain illustrates how a series of events can become linked together to affect eating and activity behaviors. The behavior chain helps identify where the individual can intervene in the future to prevent unwanted eating and inactivity. Thus, the individual might plan to get additional sleep and prepare meals the night before in case he oversleeps.

Figure reprinted from Brownell (15).

Structure of Treatment

Behavioral treatment is typically delivered in groups of 10–15 individuals in a closed group format (all participants begin the treatment program at the same time) for 60–90 minutes per session. The group format provides valuable social support; participants help each other identify and develop strategies for overcoming barriers to their eating and activity goals. Group treatment appears to result in larger weight losses than individual treatment. A randomized controlled trial found that participants in group treatment lost significantly more weight than those assigned to individual treatment, even among those who preferred to receive individual care (14). Group sessions are initially held weekly during the weight loss phase (16–26 weeks) and are followed by bi-weekly meetings that focus on the maintenance of weight loss.

Treatment sessions typically begin with the clinician privately measuring the weight of each participant. During this weigh-in, the participant is told how much his weight changed since the previous week, as well as the total amount of weight change since beginning treatment. The clinician takes a moment to offer praise for successful weight loss (or weight loss maintenance) and responds supportively to participants who are disappointed with their weight change. When the group meeting begins, the clinician asks each participant to provide a report of her homework assignment and her success in meeting calorie and activity goals. Typically, participants will report the average number of calories they consumed in the previous week and the total minutes of physical activity they completed in the previous week. During this review, participants help each other generate solutions for addressing barriers to eating and activity goals. The remainder of the session is devoted to the presentation and discussion of new material designed to enhance participants’ weight management skills, such as responding to cues for eating and inactivity, finding time to exercise, making healthy choices on weekends and holidays, and modifying recipes. Time is reserved at the end of each session to assign homework and review goals for the upcoming week.

Components of Behavioral Treatment

Behavioral treatment is delivered as a package that is comprised of multiple components designed to facilitate changes to eating and activity habits. These procedures have been described in detailed treatment manuals, such as the LEARN Program for Weight Management (15) and the Diabetes Prevention Program’s Lifestyle Change Program (16). The present chapter describes self-monitoring, stimulus control, problem-solving, cognitive restructuring, and relapse prevention. Additional research is needed to identify the most effective components of treatment.

Self-Monitoring of Eating, Physical Activity, and Weight

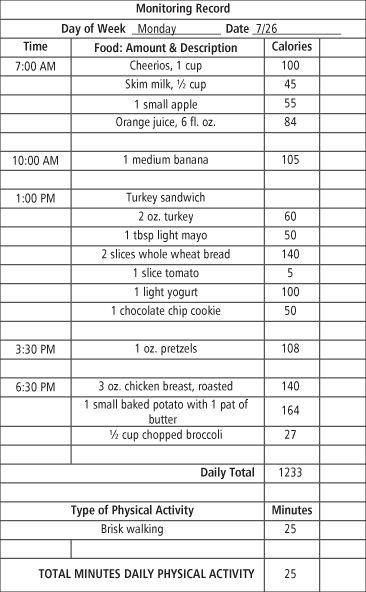

Self-monitoring is the cornerstone and perhaps the most important component of behavioral treatment for obesity (15, 17, 18). Obese individuals have been shown to underestimate their food intake and over-report their physical activity by as much as 50% (19). Therefore, participants are taught to keep records of their food intake, physical activity, and weight throughout treatment. Participants record detailed information about the types, amounts, and calorie content of the foods and beverages they consume, as well as the duration and form of exercise they complete (see Figure 15-2 for an example). Participants receive training in reading food labels and using measuring utensils (e.g., scales, cups, spoons) in order to enhance the accuracy of their food records.

Figure 15-2 Sample Food and Exercise Monitoring Record

Self-monitoring is the cornerstone of behavioral treatment for obesity. Participants begin by recording the times, amounts, and calories of foods consumed and the physical activity they engaged in. The extra column can be used to monitor additional contextual information (e.g., places, feelings) throughout treatment in order to help identify problematic behavior patterns that can be targeted for intervention.

As treatment progresses, additional contextual information (e.g., location of eating, hunger ratings, feelings) can be added to the food record in order to identify triggers of problematic eating. An individual, for example, might notice that he tends to overeat in the evenings when he does not have an afternoon snack. Another may realize that she consumes more calories at lunch on workdays if she eats at a fast-food restaurant rather than bringing lunch from home. Records can reveal social circumstances or even people that trigger problematic eating or other circumstances that undermine efforts to be more physically active. Once problem areas have been identified, a plan for overcoming the obstacle can be developed.

There is considerable empirical support for the use of self-monitoring in behavioral treatment for obesity. Several studies have found that individuals who regularly keep food records lose significantly more weight than those who record inconsistently (20–23). For example, Berkowitz and colleagues (20) compared the weight losses achieved by obese adolescents who most consistently completed self-monitoring records to those who were less adherent with their food recording. They found that participants who self-monitored more frequently achieved a greater reduction in body mass index (BMI) than patients who self-monitored less frequently (11.5% vs. 6.3%, respectively) during the first six months of treatment (20).

Self-monitoring likely reduces the tendency to underestimate food intake by increasing awareness of eating behaviors. It prevents a participant from forgetting about the Hershey Kisses she ate from a co-worker’s candy dish or the “tasting” she did while cooking dinner for her family. Participants often report that it keeps them “accountable.” Food records may be especially beneficial during periods of high risk for weight gain, such as holidays (24, 25).

Self-monitoring of body weight has also been shown to be associated with successful weight control (26–28). Participants in behavior therapy are instructed to weigh themselves at home in addition to their weekly weigh-in with their therapist. Their weights can be tracked visually using weight graphs, which provide participants with a visual representation of their progress throughout the program. A study of successful weight loss maintainers found that over three-quarters of the sample weighed themselves at least once per week (26). Furthermore, participants who decreased their self-weighing frequency over a one-year period gained significantly more weight than those whose self-weighing frequency increased or stayed the same (26). Self-monitoring of weight may help participants catch small weight gains and make the necessary behavior changes to prevent additional weight gain.

Stimulus Control

Stimulus control techniques use the principles of classical and operant conditioning to help participants make their environments more conducive to healthy eating and exercise. As described previously, an event can become a cue to eat when it is repeatedly paired with eating. For example, walking into the kitchen often elicits a desire to eat because this room is strongly associated with food. People rarely experience a food craving when in the attic because of the absence of food cues in this area. Several studies provide evidence of environmental influences (i.e., proximity and visibility of food) on eating behavior. One study, for example, found that participants consumed more chocolate when the chocolates were placed on their desks (as opposed to 2 meters away) or when they were placed in clear (rather than opaque) containers (29). Another experiment reported that participants ate more chicken wings in a restaurant when the chicken wing bones were cleared as they were eating (removing a visual cue of how much had been consumed) in comparison to those whose tables were not cleared (i.e., chicken wing bones remained visible on the table) (30).

Behavior therapy incorporates several strategies in order to limit exposure to cues that prompt overeating. Participants are taught to store foods out of sight, limit the places that they eat to the kitchen or dining room, and refrain from engaging in other activities while eating (such as reading or watching television). These strategies weaken the strength of these cues by disconnecting them from eating. Stimulus control strategies are also used to create positive cues for healthy eating and physical activity. A participant might, for example, place a fruit basket on the kitchen counter in order to encourage consumption of a healthy snack. Another might move his treadmill from the basement to a more visible and possibly more pleasant place in the house to remind him to exercise. Stimulus control aims to decrease negative cues while increasing positive ones (15). One novel study found that encouraging patients to use an online grocery shopping and delivery service rather than do conventional grocery shopping reduced the number of high-fat foods in the house (31). This effect likely occurred because participants’ exposure to tempting food cues in the grocery store was reduced. Future studies are needed to evaluate the long-term impact of interventions designed to improve stimulus control in weight management programs.

Problem-Solving

Behavioral approaches teach patients that planning meals and activity schedules is an essential tool for successful weight control. Even the best “planner,” however, will encounter barriers. Therefore, problem-solving skills are taught as part of the behavioral treatment package. Participants learn to solve problems using a five-step process (32). The first step is to identify the problem in detail. It can be useful to create a behavior chain (see Figure 15-1) illustrating the events that led to the problem behavior and identify which links in the chain to target. Once the problem is clearly specified, the second step involves brainstorming potential solutions to the problem. Participants are encouraged to be as creative as possible in generating ideas. In the third step, participants consider the pros and cons of each option. Fourth, participants choose a solution and develop a plan for implementing it. The final step involves evaluating the effectiveness of the chosen solution. If the problem was not successfully solved, the process can be repeated. Research suggests that increasing problem-solving skills has been associated with improved weight loss (33) and weight loss maintenance (34).

Cognitive Restructuring

Behavioral treatment also targets negative thinking that can create obstacles to successful weight control. According to cognitive theories of behavior change, a person’s thoughts determine how he will respond to different events. For example, catastrophic and dichotomous thinking often occurs among individuals attempting to lose weight and can lead them to abandon their weight control efforts. For instance, a person may overeat and have the thought, “I’ve blown my diet, I should just give up,” and consequently continue overeating. In behavioral therapy, participants are taught to monitor their thoughts and replace cognitive distortions with rational responses. For instance, a participant may learn to respond to overeating by having the thought, “I know that was not the best choice I could have made, but I am going to stick with my plan for healthy eating for the rest of the day.” Rational responses such as “Just because I ate an extra 300 calories for lunch does not mean I will not be able to lose weight this week” are more likely to elicit positive eating and activity habits. Cognitive restructuring is helpful in teaching patients to view a setback as a temporary lapse.

Relapse Prevention

Behavioral treatment for obesity includes training in relapse prevention based on Marlatt and Gordon’s work in addictions (35) in order to help prepare a participant to maintain their weight loss in the long term. Participants are taught to anticipate and develop strategies for dealing with high-risk situations (e.g., vacations, periods of stress at work). They also learn to plan for how they will respond to “slips” from their new eating and activity habits, which are viewed as an expected part of the weight management process. Relapse prevention strategies turn slips into learning opportunities that enable participants to navigate future situations more successfully.

Dietary Components of Behavioral Treatment

Standard Dietary Treatment

Create an Energy or Calorie Deficit

Standard behavioral treatment typically recommends an intake of 1,200–1,800 calories per day to induce weight loss. Weight may be used to determine a calorie goal, with those weighing above 113.5 kg consuming 1,500–1,800 kcal/day and those less than 113.5 kg consuming 1,200–1,500 kcal/day. Given variations in energy needs based on height, weight, sex, age, customary activity level, and nonspecific individual differences, it is difficult to determine exactly what level of calorie intake will produce the desired weight loss of 0.5–1 kg per week. This is usually approximated by creating a deficit of 500 calories per day which can theoretically produce 0.5 kg of fat loss per week, but for many people, such a large deficit may feel like deprivation. With trial and error, the participant and treatment provider can determine an exact calorie goal within this range. Behavioral strategies such as self-monitoring of food intake and stimulus control are used to help participants limit food intake and meet calorie goals.

Design a Nutritionally Balanced Diet

A nutritionally balanced diet is emphasized in behavioral treatment and based on the Food Guide Pyramid. Federal guidelines suggest limiting dietary fat to less than 30% of calories, with 50% of total calories coming from carbohydrates and 20% from protein (36). Behavior therapy encourages controlling portion sizes and limiting calorie intake by consistently weighing and measuring foods. Table 15-2 presents a summary of dietary recommendations used in standard behavioral treatment.

Table 15-2 Summary of Dietary Recommendations for Weight Loss

Table reprinted from ref. (134).

| Element | Recommendation | Comments |

| Energy (kcal) | Reduce intake by 500–1,000 kcal/day | Should lead to sustained weight loss of 0.5–1 kg/wk |

| Fat | 20–30% of total energy intake | Reducing dietary fat without restricting energy is not sufficient for weight loss; include foods that are reduced in fat and energy density |

| Carbohydrates | ≥55% of total energy | Emphasize complex carbohydrates from whole grains, vegetables, and fruit |

| Protein | 15% of total energy | Include low-fat varieties of beef and pork, roasted poultry without skin and fish |

| Alcohol | Limit to 1 drink/day for women; 2 drinks/day for men | Consume with meals |

| Fiber | 20–30 g/d | Choose whole grains, fiber-rich breakfast cereals, whole fruits, vegetables, and legumes |

Aside from the balanced deficit diet frequently used in behavior therapy for obesity, there are several alternative nutritional components that may be used to help meet energy deficit goals. Some of these approaches are designed to produce greater initial weight losses, while others focus on facilitating greater long-term adherence to calorie goals (37–39). Examples of these approaches include very-low-calorie diets, meal replacements, portion-controlled diets, low-carbohydrate diets, and low energy-density diets. Each of these is discussed briefly in this section.

Very-Low-Calorie Diets (VLCDs)

VLCDs were widely used in weight loss treatment programs in the 1980s and early 1990s (40) and are occasionally used in treatment today. They are defined by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute as diets providing less than 800 kcal/day (41). This definition, however, fails to take into account individual dietary needs and deficits, such as the impact that sex, level of obesity, and age might have on daily energy expenditure and necessary energy deficit. Investigators therefore suggest defining VLCDs as any diet that provides ≤50% of an individual’s predicted resting energy needs (42, 43). VLCDs are designed to produce rapid weight loss while maintaining lean body mass, especially muscle, organ tissues, and bone. They typically consist of high-protein shakes that are consumed 4–5 times per day, in addition to multivitamin and mineral supplements (44). Popular commercial versions of VLCDs are produced by Optifast and Health Management Resources. VLCDs are considered safe and effective when used by appropriately selected obese individuals. Contraindications can include a diagnosis of bulimia nervosa, major depressive disorder, substance abuse disorders, or any acute psychiatric illness that would impair dietary adherence. Patients need to be examined by a physician regularly (e.g., twice a week) during weight loss (45). Side effects can include hair loss, fatigue, dizziness, and increased risk of gallstones. Unsupervised use of VLCDs can result in serious complications, particularly when used for long periods without close medical supervision.

Research suggests that VLCDs produce rapid and significant weight losses of 20–25% of initial body weight during 12–16 weeks of treatment (42). These weight losses, however, are not well maintained. Even when combined with behavior therapy, patients typically regain 35–50% of lost weight in the year following treatment, and all weight lost is often regained within 3–5 years of treatment (44). Tsai and Wadden (42) conducted a meta-analysis of six studies that conducted randomized comparisons of conventional low-calorie diets to VLCDs and had a follow-up assessment of at least one year after maximum weight loss. The VLCDs in the six studies produced greater short-term weight losses but comparable long-term losses and similar rates in attrition. While the rapid weight losses of VLCDs are appealing to some patients in the short term, the lack of effective weight loss maintenance strategies at the end of active weight loss treatment is concerning, and there are no adequate data to suggest that the rapid weight losses experienced in the first 12 months of treatment result in greater health improvements than with standard low-calorie diets (44).

Meal Replacements

One promising alternative to a VLCD is the use of a meal replacement diet. Originally developed as over-the-counter modifications of VLCDs, meal replacements are defined as functional foods in the form of drinks or bars as a meal replacement (46). The best-known meal replacement is Slim-Fast. Behavioral therapy programs that use meal replacements generally recommend that patients replace two meals and one or two snacks each day with a meal replacement. The remaining meal is comprised of self-selected conventional foods, such as a dinner of chicken, rice, and a vegetable. A meal replacement diet contains more calories and therefore a more complete micronutrient profile than a VLCD. Meal replacements are considered safe when used as directed and can be readily incorporated into behavioral treatment. By reducing the variety of foods in the diet and increasing dietary structure, meal replacements facilitate adherence to the daily calorie goal. Patients can also learn to use meal replacements in situations in which they would otherwise engage in disinhibited eating or make unhealthy food choices. For example, patients can be encouraged to keep meal replacements in their car for situations in which they might otherwise eat at a fast-food restaurant (e.g., running late to a meeting). Meal replacements are very convenient, require little preparation, and allow dieters to avoid contact with problem foods (42). Relative to some other types of food (e.g., fast-food meals, frozen meals) they are also inexpensive. Importantly, meal replacements eliminate the need to make decisions about which and how much food to eat. Thus, they might facilitate a more accurate estimation of calorie intake, which, as noted previously, is a challenge for many obese individuals (19).

There is strong evidence that the use of meal replacement facilitates weight control (47). A meta-analysis of seven randomized trials found that patients who used meal replacements lost an average of 4 kg more after six months (and 3.8 kg more after 12 months) than those who followed a conventional weight loss diet (48). Meal replacements might be especially useful for promoting long-term weight control. Flechtner-Mors and colleagues (49) found that patients who continued to substitute one meal and one snack each day with meal placements after initial weight loss maintained a weight loss of 11% after 27 months and 8% after 51 months.

Some treatment providers or patients may be concerned that the use of meal replacements and other highly structured diets may induce binge-eating or foster poor eating habits (47). Research indicates that this is not the case. Wadden and colleagues (50) conducted a randomized controlled trial to examine the effects of weight loss dieting on binge-eating among obese individuals without a prior history of eating disorders. Patients were randomized to one of three conditions: 1) a balanced deficit diet of 1,200–1,500 kcal/day, 2) a non-dieting treatment (which discouraged caloric restriction), and 3) meal replacements. Patients in the meal replacement condition were initially prescribed a completely liquid diet of 1,000 kcal/day for 14 weeks, after which they gradually decreased their consumption of meal replacements until they were consuming 1,200–1,500 kcal/day of self-selected foods (similar to the balanced deficit diet condition). After 65 weeks, no differences emerged between groups in binge-eating or mood changes (50).

Additional concerns have been raised about whether meal replacement diets provide adequate nutrition. In order to assess this concern, Ashley and colleagues (51) compared the nutrient intake of participants randomized to a conventional food or meal replacement group. They found that patients in the meal replacement condition had a higher intake of vitamins and minerals than those who consumed a diet of conventional foods. Meal replacements are also safe to use with those with type 2 diabetes and have not been found to adversely affect glycemic control (47). While it is unclear whether meal replacements are superior to other dietary approaches that provide a similarly high level of structure and portion control, it appears that meal replacements are an appropriate nutritional component to use as part of behavioral treatment for obesity.

Portion-Controlled Diets

VLCDs and meal replacements are both designed to address the challenges of a conventional food diet, which requires the dieter to make food choices and estimate portion sizes at every meal. Portion-controlled diets offer another approach for addressing these challenges. Structured, portion-controlled diets help avoid cues for overeating by simplifying choices, reducing variety, limiting temptation, and eliminating the need for laborious food preparation (52). They also address the common problem of food intake underreporting (19), which can occur when individuals underestimate portion sizes, fail to recognize hidden sources of fat and/or sugar, or forget some foods eaten.

Several studies have shown that portion-controlled servings of conventional foods improve both the weight loss phase and the maintenance of weight loss phase. Jeffery and colleagues (53) found that participants who were prescribed a diet of 1,000 kcal/day and provided with five breakfasts and five dinners a week lost significantly more weight at 6, 12, and 18 months than participants who were prescribed the same number of calories but consumed a diet of self-selected foods. A follow-up study (54) compared weight losses among groups that received standard behavioral treatment combined with (a) no additional structure; (b) structured meal plans and grocery lists; (c) meal plans with food provided at reduced cost; or (d) meal plans with free food provision. Although the calorie goals were equivalent across groups, participants in the last three groups lost significantly more weight after six months of treatment and maintained greater losses at an 18-month follow-up than did those who received no additional structure, which suggests that structure alone, as provided by prepackaged, portion-controlled meals, was enough to improve weight control. Many other studies have demonstrated the benefits of using pre-packaged, portion-controlled meals, including frozen-food entrées, for weight loss (4, 55–58). As with meal replacements, pre-portioned items like frozen entrées eliminate the need to weigh and measure food and they save time planning and preparing meals (44). When combined with behavior therapy, portion-controlled meals make self-monitoring easier and reduce the need to weigh and measure foods, potentially making adherence to treatment goals easier.

Low-Carbohydrate Diets

Low-carbohydrate diets have been studied extensively in recent years (59–64). These diets limit carbohydrate intake to 50–100 g daily, without restrictions in dietary fat or calories. The consumption of high-protein foods has been shown to promote satiety (e.g., 65–69). Furthermore, limiting intake of an entire class of macronutrients—in this case, carbohydrates—might also facilitate calorie restriction. Three randomized controlled trials have compared low-carbohydrate and low-fat diets: two found no weight loss differences between groups at one year (60, 62), and one provided favorable long-term support for a low-carbohydrate diet (64). In the largest long-term randomized controlled trial (70) conducted to date, four diets were compared. At two years, weight loss was similar in groups that were assigned to a diet with low- or high-protein, low- or high-fat, and low- or high-carbohydrates. Taken together, these findings indicate that calorie intake, not macronutrient composition, determines long-term weight loss maintenance. However, the amount or type of macronutrient (e.g., simple vs. complex carbohydrates or saturated versus unsaturated fats) may have important health implications, particularly for conditions such as type 2 diabetes or cardiovascular disease.

Low Energy-Density Diets

Low energy-density diets present yet another option for weight control. Energy density is defined as the amount of calories in a given weight of food (kcal/g). The principal rationale for a low energy-density diet is that, for the same amount of calories, a greater volume of food can be consumed when the food is low in energy density than when its energy density is high. Thus, a low energy-density diet allows people to eat a satisfying amount of food while limiting energy intake (71). Low energy-density diets are also typically of high nutritional quality. Data from the Continuing Survey of Food Intakes by Individuals indicate that individuals who eat low energy-density diets, compared to those who eat high energy-density diets, consume fewer calories, a greater volume of food, less fat, and more micronutrients, including vitamins A, C, and B6, iron, calcium, and potassium (72).

Several randomized clinical trials support the effectiveness of energy density interventions. In one clinical trial (73), the intervention group was instructed to incorporate portions of fruits, vegetables, broth-based soups, and other low energy-density foods into their diet ad libitum, and to prepare and choose foods with less fat. The comparison group was instructed to reduce their portion size of all foods and reduce their fat intake. Weight loss in the intervention group was significantly greater at six months than in the comparison group (9 kg vs. 6.7 kg, respectively). In another study (74), obese women were randomly assigned to a weight loss condition that emphasized reducing fat intake or one that emphasized reducing fat and increasing intake of water-rich foods, especially fruits and vegetables. Participants in the low-fat only group lost significantly less weight at six months than participants in the combined group (6.7 kg vs. 8.9 kg, respectively), but weight loss maintenance at 12 months was not significantly different between groups (6.4 kg vs. 7.9 kg). Of note, participants in the condition that emphasized water-rich food intake reported significantly less hunger than those in the low-fat only group. A low energy-density diet could be an excellent option for dieters who struggle with hunger. This approach would let them eat more food while potentially decreasing their food intake.

Physical Activity Components of Behavioral Treatment

Physical activity is widely recognized as an essential component of weight loss treatment. Participants in behavioral treatment programs set specific goals for physical activity and receive support for increasing and then maintaining a high level of physical activity (75–76). Engaging in physical activity without concurrent caloric restriction is of limited benefit in inducing weight loss (77). However, combining dietary restriction with increased physical activity facilitates weight loss and helps prevent weight regain (77). Physical activity appears to influence the composition of weight loss so that a higher proportion of the weight loss is loss of fat and a smaller proportion is fat-free mass, which is metabolically desirable (78). This may help offset the reduction in resting metabolic rate that results from weight loss (78). Engaging in physical activity during weight loss might also facilitate dietary adherence and better prepare participants for weight loss maintenance (78–79).

Physical activity appears to be a critical component of successful weight loss maintenance (76, 80–81). A meta-analysis of 18 randomized weight loss trials found that combined diet-plus-exercise interventions produced greater long-term weight loss than interventions that only included diet, particularly in interventions lasting longer than one year (82). Members of the National Weight Control Registry report maintaining their weight losses by engaging in approximately one hour per day of physical activity, through which they expend an average of approximately 2,825 kcal per week (83). Other studies have reported similar results: those who consistently engage in physical activity following weight loss have a higher likelihood of maintaining their weight losses (82, 84–85). Physical activity is also important in reducing the risk for several chronic diseases and medical conditions that are especially prevalent in the obese (e.g., coronary heart disease, diabetes, hypertension). Other benefits of physical activity include reduced stress, increased emotional well-being, reduced depression (and possibly therefore reduced emotional eating), increased energy level, improved sleep, and improved self-confidence (79). Emphasizing the role physical activity has on these benefits is imperative when encouraging lifestyle modification.

Recommended Amount of Physical Activity

The Centers for Disease Control and Intervention, the American College of Sports Medicine, and the American Heart Association recommend that healthy adults age 18–65 years engage in 150 minutes of exercise of moderate or greater intensity (between 60–80% maximum age-adjusted heart rate) each week (78). This level of activity produces energy expenditure of approximately 1,000 kcal per week. This recommendation is useful for preventing weight gain in normal weight individuals, but greater amounts are needed for weight loss and weight loss maintenance. The American College of Sports Medicine recommends 200–300 minutes per week of moderate-intensity activity for long-term weight loss (85). Additional research, reviewed next, suggests that the amount of physical activity necessary for weight loss maintenance may be even higher than that.

Jeffery and colleagues (84) compared an 18-month behavioral weight loss treatment program combined with two different levels of physical activity, equivalent to either 2,500 or 1,000 kcal per week of energy expenditure. Participants assigned to complete the higher level of physical activity (equivalent to approximately 75 minutes per day of brisk walking) experienced significantly greater initial weight losses and greater weight loss maintenance at 18 months than those told to complete a lower level of physical activity. However, most participants were unable to sustain this high level of physical activity after 18 months, so group differences were no longer apparent by 30 months (86). Of note, those participants who were able to sustain a high levels of physical activity (i.e., expending at least 2,500 kcal per week with exercise) maintained significantly larger weight losses at 30 months than those participants whose engaged in a lower level of physical activity (12 kg vs. 0.8 kg). Jakicic and colleagues (87) found similar (non-experimental) results among obese participants in a behavioral treatment program: participants who were exercising 200 minutes or more per week lost more weight and had significantly greater weight loss maintenance at 18 months than did those who exercised less. Other research indicates that 70–80 minutes per day of moderate intensity activity is needed to prevent weight regain in the year after weight loss (81).

The Role of Type of Exercise

It should be noted that while the physical activity component of behavior therapy focuses primarily on cardiovascular activity (e.g., brisk walking) because of its calorie-burning contribution to weight loss, muscle-strengthening activities should be encouraged as well. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommend that adults engage in muscle-strengthening activity at least two days per week, working all the major muscle groups (88). Mild-to-moderate resistance training is an effective method of improving muscular strength and endurance, preventing and managing a variety of chronic medical conditions, modifying coronary risk factors, and enhancing psychosocial well-being (89). There is also some evidence that muscle strengthening can help preserve fat-free mass during weight loss and that preservation of fat-free mass enhances maintenance of resting metabolic rate following return to energy balance (90). Muscle-strengthening activities should serve as a complement to, rather than a replacement for, the patient’s cardiovascular activity prescription (89).

Meeting Physical Activity Goals

Facilitating changes in physical activity is notoriously difficult. Fewer than one-third of adults in the US meet the minimum recommended levels of moderate physical activity, defined as at least 30 minutes per day (91–92). Adults who do not meet recommended physical activity goals commonly report that they face barriers such as limited time, cost, lack of resources, childcare, fatigue, and health problems (79).

To reinforce the importance of physical activity in weight loss treatment, the principles of behavior therapy are applied to increasing physical activity in much the same way as dietary restriction. Behavior therapy encourages setting specific and measurable physical activity goals each week, as well as daily self-monitoring of activity. Self-monitoring of physical activity can be completed in the same log that is used to track dietary intake (see Figure 15-2). Individuals are encouraged to monitor the type of activity and the total minutes of activity completed each day. Physical activity goals are increased slowly over the course of behavioral weight loss treatment. For example, an initial goal might be to walk at least 10 minutes per day, four days per week (or a total of 40 minutes per week). Each week, the targeted amount of physical activity might increase by approximately 10 minutes, progressing over several months to an eventual goal of 180–200 minutes of activity a week. Pedometers can be used to track total steps taken each day. Behavioral treatment participants are asked to record the total number of steps each day on their daily monitoring form. Participants work toward an eventual goal of at least 10,000 steps per day (the equivalent of approximately 5 miles). Problem-solving also is used to identify barriers to physical activity and formulate solutions to those barriers. Lastly, stimulus control is encouraged. For example, individuals might try leaving their sneakers by the door as a reminder to go for a walk before they leave for work in the morning or they might place a treadmill in the living room as a cue to walk at home while watching television. Other ways to enhance compliance with physical activity goals include providing psycho-education regarding the importance of exercise, encouraging participants to seek social support (e.g., find a walking partner or enlist a family member to provide childcare), providing appropriate models of physical activity that match skill levels and individual preferences, and providing positive reinforcement for meeting physical activity goals.

Intermittent Vs. Continuous Activity

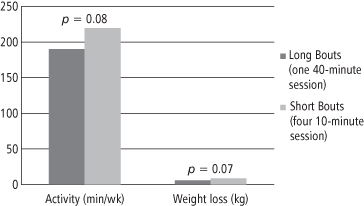

As noted previously, lack of time is frequently cited as a barrier to meeting physical activity goals. With recommended goals as high as 70–80 minutes per day, it is understandable that this is a challenge. To address this, investigators have examined whether physical activity goals can be met by performing short bouts of activity throughout the day rather than engaging in a single continuous bout. Research has demonstrated that intermittent and continuous activity of the same total duration produce equivalent improvements in cardiovascular health, weight, and fasting or postprandial lipemia (93). For example, Jakicic and colleagues (87, 94) randomized participants in behavioral weight loss treatment to follow a routine of either multiple, short bouts of activity, completed in intervals of at least 10 minutes, for 40 minutes per day, or 40 minutes of exercise completed in a single bout each day. Multiple short bouts were as effective as longer bouts in producing long-term weight losses and improving cardiovascular fitness (see Figure 15-3) (94). These studies suggest that patients can choose between, for example, 40 continuous minutes of brisk walking daily, and four, 10-minute brisk walks throughout the day. This is beneficial for those who are unable to set aside a 30–60 minute block of time each day or are overwhelmed by the idea of having to do 30 minutes of activity most days of the week. For such patients, encouraging short bouts of activity may increase compliance in treatment. Evidence also suggests that exercising throughout the day may help prevent injuries by making the intensity of activity occur in smaller bursts rather than one long burst (79). It is generally agreed that the short bouts of activity should last at least 10 minutes in order to gain cardiovascular benefits of exercise (87, 95).

Figure 15-3 Effect of Long vs. Short Bouts of Exercise on Total Amount of Activity and Weight Loss

Participants were given the same instruction on diet modification, but were told to engage in either one 40-minute bout of exercise or four 10-minute bouts of exercise throughout the day. Participants in each condition experienced similar patterns of total daily activity and weight reduction, suggesting that several small bouts of exercise are as effective as one long bout for producing weight loss.

Data reproduced from reference (94).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree