CHAPTER 7 Behaviour change

The material in this chapter will help you to:

Introduction

How healthy is your lifestyle? Do you regularly follow the health practices identified in Chapter 4 regarding nutrition, physical activity, cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption? Have you ever made a decision regarding one of these health behaviours but not continued with the activity as you intended, for example, to exercise regularly? Or perhaps you did follow through with your intention and maintained the activity. Why might there be different outcomes to these scenarios when your intention was the same in both? What other factors might influence the outcomes in these two scenarios?

Health-enhancing behaviours: why focus on them?

Up until the mid-20th century global public health threats were mainly from infectious and communicable diseases. However, in developed countries, a shift occurred over the past one hundred years whereby the major health threats are now posed by diseases in which lifestyle plays a role in the aetiology and/or management of illness. For example, the modifiable risk factors for coronary heart disease, a leading cause of disease burden, are: tobacco smoking; high blood pressure; high cholesterol level; insufficient physical inactivity; overweight and obesity; poor nutrition and diabetes (AIHW 2006 p 61), all of which are linked to health behaviours and lifestyle.

Disease burden is measured by disability adjusted life years (DALYs) which comprises years of life lost (YLLs) (mortality) and years lived with disability (YLD) (morbidity). In Australia, New Zealand and other Western nations the health conditions with the greatest disease burden (measured by DALYs and YLDs) are cancers, cardiovascular diseases, mental illness, injuries, chronic respiratory disease and diabetes (AIHW 2006). Each of these conditions, at least in part, can be attributed to lifestyle and the course of the conditions can be moderated by health behavioural practices. Hence, there is intuitive appeal in encouraging people to lead a healthy lifestyle to thereby reduce their disease risk and to improve quality of life for people with chronic health conditions.

Health psychology: theories and models

Psychological theories and models of health behaviour attempt to explain or predict an individual’s engagement in behaviours that influence the risk for illness or injury and the maintenance of health. In the main, psychological theories of health behaviour fall into two broad categories: behaviourist/learning theories and cognitive theories. Behaviourist/learning approaches include operant conditioning, classical conditioning and modelling or imitation (see also Chapter 1). Cognitive approaches include the health belief model and the transtheoretical model of behavioural change. The theory of planned behaviours introduces social influences to a cognitive model as does the health action process approach. These behavioural and cognitive approaches to behaviour change will now be examined.

Learning theories

Classical conditioning

As outlined in Chapter 1, classical conditioning was first described by the Russian Ivan Pavlov who observed the relationship between stimulus and response through demonstrating that a dog could learn to salivate (respond) to a non-food stimulus (a bell) (Pavlov 1927).

Operant conditioning

B F Skinner formulated the notion of instrumental or operant conditioning in which reinforcers (rewards) contribute to the probability of a response being either repeated or extinguished. Skinner’s research demonstrated that the contingencies on which behaviour is based are external to the person, rather than internal. Consequently, changing contingencies could alter an individual’s behaviour (Skinner 1953).

Observational learning theory

Observational learning theory (also called modelling or social learning theory) was proposed by Bandura (1969, 2006) who asserts that observational learning has a more significant influence on how humans learn than intrapsychic (psychoanalytic) or environmental (behaviourist/learning) forces alone. Bandura proposed that human behaviour results from interaction between the environment and the person’s thinking and perceptions. He also asserted that humans learn from observing not only by doing. Observational learning differs from operant conditioning in that it is not the learner who is rewarded for the behaviour; rather, the learner observes the other person being rewarded and learns vicariously through this.

Observational learning is particularly important for children’s learning because it is easier to influence a behaviour while it is being acquired rather than changing an established behaviour (Niven 2000). Hence parents and family play a significant role in the health habits that children acquire. These habits can be both positive health behaviours, such as participating in sport, or negative, such as tobacco smoking.

Learning theory approaches

Have you ever received a parking fine, a speeding ticket, lost your driver’s licence, been locked out of a concert until interval because you arrived late or been refused borrowing rights at your library until you paid your fine for late returns? Do you feel motivated after your boss tells you that he is impressed with your work or smile back at someone who has just smiled at you? Most of us, without realising it and without being able to use the technical terminology of behavioural change programs, actually practise behaviour modification in our everyday lives and have it practised on us. In your various roles as citizens, partners, parents, friends and professionals, you will, by the end of this chapter, be surprised to discover how much of your own behaviour is governed by the fundamental principles of learning theory, on which behavioural change programs are based, and how much of the behaviour of those around you is at least partly determined by your own behavioural change strategies.

Behaviour change programs

These four tenets underpin the four major theoretical models that have been derived from learning theory, namely, classical conditioning, operant conditioning observational (imitation) learning and cognitive behaviourism (Ellis 1984, Beck 1976, Meichenbaum 1974).

Historically, behaviour therapy referred to the techniques based on classical conditioning, devised by Wolpe (1958) and Eysenck (1960) to treat anxiety; behaviour modification was used to describe programs based on the principles of operant conditioning devised by Skinner (1953) to create new behaviours in children who had an intellectual disability and patients with psychotic symptoms.

FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS OF BEHAVIOUR

Specifying these contingencies forms the basis of a functional analysis of behaviour. The aim of a functional analysis is to identify factors that influence the occurrence and maintenance of a particular (problem) response. This process should not be confused with other explanatory models that may seek to explain behaviour in terms of a medical diagnosis or a personality trait. Behaviour change programs are more concerned with the nature of our interactions with the environment than with our nature per se.

2. IDENTIFYING CURRENT CONTINGENCIES

The second step requires the identification of the consequences that follow the problem behaviour; that is, what happened after the behaviour was performed? To follow through with our examples above, did the parents respond to the child’s tantrum by giving the child what s/he wanted or did they ignore his/her tantruming behaviour? Did they engage in a verbal debate with the child when he talked back or did they calmly state their rule that talk backs would not be answered? Were there any differences in each of the two nurses’ responses to Mr Stone’s buzzer ringing? What was the mother doing in the treatment room to discourage her child’s physiotherapy exercise practice? Answers to these questions are essential for effective behavioural management to occur.

3. MEASURING AND RECORDING BEHAVIOUR

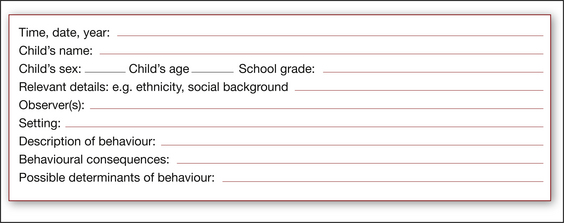

Narrative recording

Narrative recording involves the observation and recording of behaviour in progress. It is often used in the early stages of the functional analysis of behaviour as a way of identifying possible antecedents and consequences of a given problem behaviour. Figure 7.1 provides an example of a narrative recording chart.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree