21

Benign and Malignant Childhood Epilepsies

Epilepsy is one of the most common chronic neurological disorders in children, with an incidence of 33–82 per 100,000 children. It is most likely to begin early, with the highest incidence rates in the first year of life. Fortunately, approximately 60% of children will outgrow their epilepsy, becoming seizure-free and discontinuing antiepileptic medication. Conversely, approximately 20% are medically intractable, continuing to have uncontrolled seizures despite trials of two or more antiepileptic drugs.

This chapter will provide an overview of the various types of epilepsy syndromes and constellations (see Chapter 2 on classification) that occur in the pediatric age range, outside the neonatal period (see Chapter 20 on neonatal epilepsy). Those epilepsies that are pharmacoresponsive and self-limited are “benign,” whereas the epilepsies that respond poorly to antiepileptic medications (pharmacoresistant), are not self-limited, and are associated with encephalopathy that is present or worsens after seizure onset (i.e., epileptic encephalopathy) are designated “malignant.”

TIPS AND TRICKS

TIPS AND TRICKS“Benign” childhood epilepsies

Infantile onset

Benign infantile epilepsy/benign familial infantile epilepsy

The benign infantile epilepsies comprise several entities, all self-limited and associated with favorable neurological and intellectual outcome (Table 21.1). Benign (nonfamilial) infantile epilepsy presents in neurologically normal infants in the first year of life. Seizures can be focal dyscognitive, with motion arrest, decreased responsiveness, and mild clonic activity, or can evolve to generalized tonic–clonic activity. Seizures typically occur in a cluster over several days and are very pharmacoresponsive. The interictal EEG is normal. Ictal recordings show temporal foci with focal dyscognitive seizures and centroparietal foci in those that evolve to bilateral convulsive activity. Neuroimaging is normal.

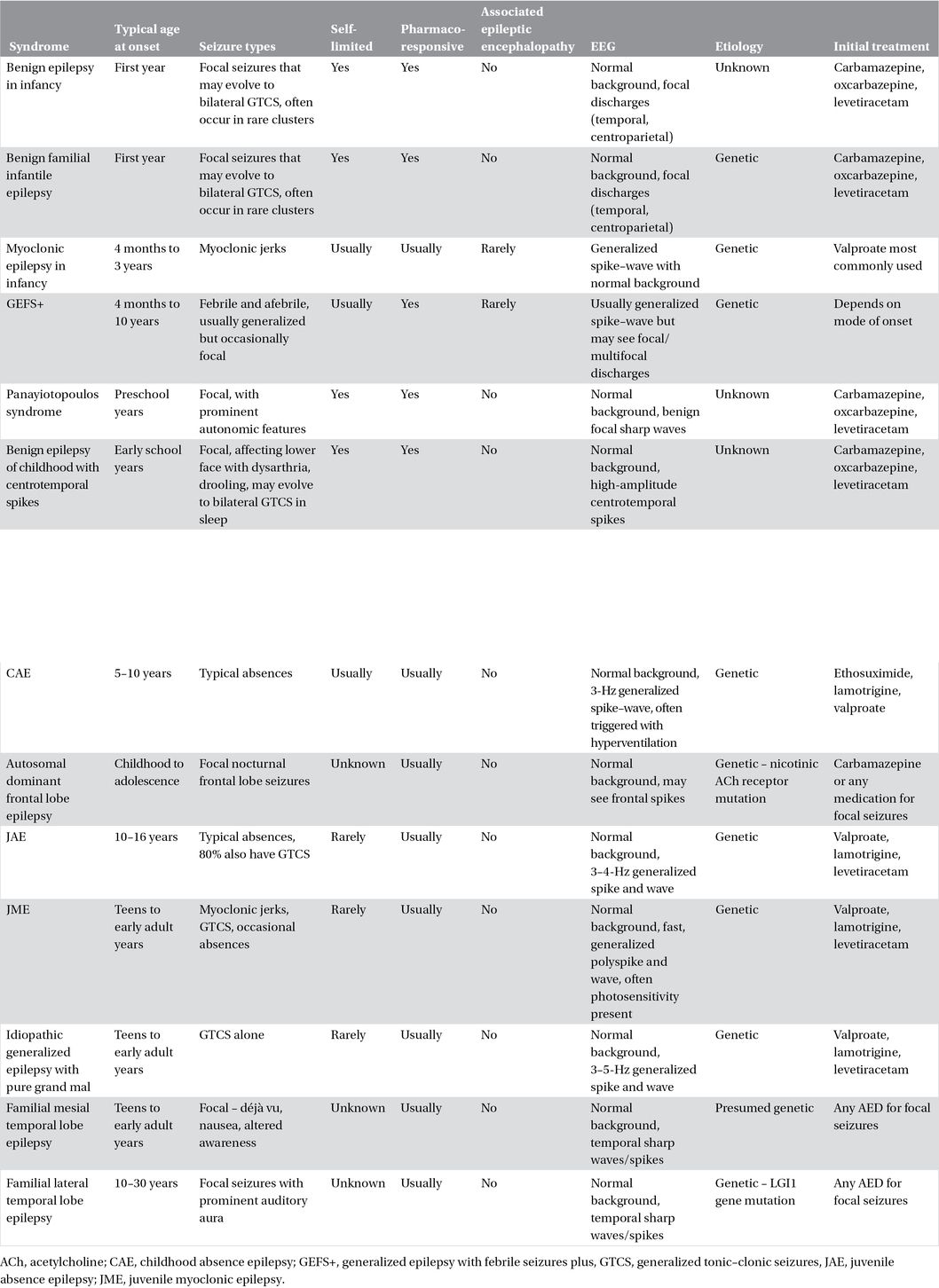

Table 21.1. Pharmacoresponsive childhood epilepsies.

Benign familial infantile epilepsy also affects otherwise healthy infants, with onset between 2 and 20 months of focal dyscognitive seizures, often clustering. Similarly affected family members are usually identified, as this entity is autosomal dominant. Three genetic loci have been identified: chromosomes 19 and 2, which lead to seizures alone, and chromosome 16, which leads to seizures with choreoathetosis. The EEG is normal interictally and shows occipitoparietal discharges with ictal recording.

Other “benign” infantile epilepsies have been described but have significant clinical overlap. These disorders may be best distinguished based on genotype.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Myoclonic epilepsy in infancy

Myoclonic epilepsy in infancy is rare and presents with myoclonic seizures starting between 4 months and 3 years of age in otherwise healthy infants. Myoclonus is often subtle at presentation but increases in intensity and frequency. Nearly one-third have preceding febrile convulsions and a few progress to generalized tonic–clonic seizures (GTCS). A family history of generalized epilepsy is present in one-third. The EEG shows generalized spike–wave and polyspike that can correlate with the myoclonic jerks, with a normal background. Valproate is often first used, but other medication including ethosuximide, benzodiazepine, levetiracetam, and phenobarbital may be effective. Epilepsy is usually self-limited, and most infants can discontinue medication early in the toddler years. Despite seizure remission, intellectual and behavioral disability occurs in a substantial minority. This entity must be distinguished from West syndrome, myoclonic–atonic epilepsy, Dravet syndrome, and underlying neurometabolic disorders.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Childhood onset

Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+)

Generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus (GEFS+) is a common syndrome, presenting between 4 months and 10 years of age. The family history is characteristically positive for febrile and afebrile seizures, as the inheritance is autosomal dominant with incomplete penetrance (60–90%). GEFS+ is genetically heterogeneous with several loci now identified, including SCN1A, SCN1B, and GABRG2. The diagnosis is clinical – genetic testing is not required and does not alter clinical management. Children typically begin with febrile seizures that may continue beyond the age of usual remittance. Additionally, many develop afebrile seizures that can be generalized (generalized tonic–clonic, atonic, absence, myoclonic) or focal. Neuroimaging is normal and the EEG usually shows generalized interictal discharges, although focal and multifocal discharges may also be seen. Prophylactic antiepileptic medication should be considered for recurrent afebrile seizures and should be based on mode of onset. For children with generalized spike–wave, carbamazepine is best avoided as it may provoke absence seizures. Long-term epilepsy and intellectual outcome is variable. In most cases, epilepsy is pharmacoresponsive and self-limited. However, severe cases with associated epileptic encephalopathy and evolution to myoclonic–atonic epilepsy or Dravet syndrome occur.

Panayiotopoulos syndrome

This relatively common syndrome usually presents with infrequent focal autonomic seizures in healthy preschool-aged children. Two-thirds of seizures occur out of sleep – the child wakes with unilateral eye deviation, retching, vomiting, pallor or tachycardia, and possible confusion. Seizures may evolve to become hemiconvulsive or generalized tonic–clonic. Prolonged seizures longer than 30 min, often with ictus emeticus, occur in approximately one-third. Interictal EEG shows normal background with high-amplitude, multifocal sharp waves significantly increasing with drowsiness and sleep. Imaging is normal. Many children can be managed with abortive agents only and may not require prophylactic antiepileptic medication if seizure frequency is low. This epilepsy always remits in childhood, typically within 1–2 years of onset, with excellent long-term intellectual outcome.

Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes (BECTS)

Benign epilepsy of childhood with centrotemporal spikes is one of the most common epilepsy syndromes in childhood, accounting for approximately 15% of new-onset epilepsy. Etiology is unknown. However, a familial predisposition is likely, as family members frequently show similar EEG changes during the early school years. Seizures typically begin between 5 and 10 years and occur after falling asleep or in the 1–2 h before waking. Nocturnal seizures frequently manifest as drooling, dysarthria, tingling, or clonic activity of the unilateral lower face, which can spread to the ipsilateral upper extremity or become secondarily generalized. If seizures occur out of wakefulness, they typically involve motor or sensory symptoms of the unilateral lower face with intact awareness. The EEG shows characteristic high-amplitude sharp waves in the centrotemporal regions, increasing with drowsiness and sleep. Imaging is normal, although it is not needed in classic cases. If treatment is needed, most cases are pharmacoresponsive, and many antiepileptic agents are efficacious. Epilepsy is self-limited – most patients can discontinue medication after 1–2 years and remain seizure-free. Intellectual outcome is usually excellent, although rare cases evolve early in the course to show a continuous spike–wave pattern in sleep, with cognitive and language regression.

CAUTION!

CAUTION!Childhood absence epilepsy (CAE)

This common syndrome presents in healthy children between the ages of 3 and 10 with a peak at 6–7 years of age. Absence seizures are characteristically the only seizure type and occur 20–50 times per day. Hyperventilation will usually trigger an absence event in an untreated or undertreated child. Children are typically aware of missed time only with longer events. Untreated seizures may result in a decline in academic performance or in injury.

Imaging is not required and the EEG shows typical 3-Hz generalized spike–wave. A paroxysmal posterior delta rhythm is commonly seen, but otherwise the background is normal.

Antiepileptic drug (AED) therapy should be initiated given the frequent seizures. A comparative effectiveness study showed that ethosuximide and valproic acid were more effective than lamotrigine and that ethosuximide had fewer adverse attentional effects.

Childhood absence epilepsy is self-limited in approximately two-thirds of children. Patients who achieve seizure freedom for 2 years with resolution of the generalized EEG discharge should be considered for a trial off medication. A few children will continue to have absences into adulthood or will develop GTCS in their adolescent/young adult years and require ongoing antiepileptic therapy. Despite remission of epilepsy, a significant minority of young adults experience increased academic and social difficulties, suggesting comorbidities such as psychiatric disorders, attention problems, and academic difficulties that must be addressed.

Autosomal dominant frontal lobe epilepsy

This autosomal dominant syndrome results from known mutations in the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor genes and has 80% penetrance. Affected family members may be undiagnosed, and a history of “parasomnias” or other “behavioral” problems in sleep should be sought. Nocturnal seizures, with brief dystonic posturing, hypermotor activity, complex behaviors, and moaning, typically begin in childhood to early adolescence. Ictal EEG may be normal but more commonly shows bifrontal, high-voltage sharp and slow waves or low-amplitude, fast frontal activity with the clinical seizure. Imaging is normal. Genetic testing is available commercially and should be considered in cases where a family history is found. Most patients respond well to antiepileptic medication such as carbamazepine. The long-term remission rate has not been well studied. However, seizures may persist through life.

Focal epilepsy of unknown cause

Focal epilepsy of unknown cause accounts for a significant minority of pediatric epilepsy, nearly 30% in one study. Many cases had a favorable long-term outcome, with 81% being seizure-free at last follow-up (68% of whom had discontinued antiepileptic medication) and only 7% developing medically intractable epilepsy. However, this group is heterogeneous and comprises other etiological categories that are, as yet, unrecognized. Further investigation will likely identify specific genes or other etiologies that determine prognosis.

Adolescent onset

Juvenile absence epilepsy

Juvenile absence epilepsy (JAE) presents in healthy patients, 10–16 years of age, slightly later than CAE. Absences are usually the initial seizure type, although 80% develop GTCS within 2 years. Absences are less frequent than in CAE, being seen up to 2–3 times per day. The EEG shows a normal background with 3.5–4-Hz generalized spike–wave discharge, at times polyspike and wave. First-line therapy should include medication active against both absence and GTCS, such as lamotrigine or valproic acid. Seizures are usually pharmacoresponsive, but most patients require lifelong therapy.

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy

Juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) accounts for 4–10% of all epilepsies, presenting between 12 and 18 years in neurologically normal patients. The most common initial seizure type is myoclonic seizures, frequently not recognized as significant, being attributed to early morning “clumsiness” or “the jitters.” Most present to medical attention after their first GTCS. Approximately 40% have coexisting absence seizures, although these are often infrequent, brief, and without complete loss of awareness. Seizures tend to occur in the early morning, particularly following sleep deprivation, and often begin with a shower of myoclonus culminating in a generalized tonic–clonic event. Photic stimulation may also be a trigger. The EEG is abnormal in most untreated patients showing 4–6-Hz generalized atypical polyspike-and-wave discharges. Up to 30% may also show focal discharges and 30–90% show photosensitivity.

Valproate has been traditionally a first-line therapy. Given its potential side effects including weight gain, teratogenicity, and polycystic ovarian syndrome, other agents such as lamotrigine, topiramate, or levetiracetam are often used first line, particularly in women of childbearing age. JME is pharmacoresponsive, with 85–90% achieving seizure control on appropriate medication. Remission is rare – only 10% of patients successfully discontinue antiepileptic medication and remain seizure-free.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree