Figure 9.1

In these side (a) and front (b) views of an artist’s impression of a brain AVM, note the abnormal tangle of vessels, nidus, with feeding arterial vessels and draining veins (Courtesy, The Aneurysm and AVM Foundation. © 2013 The Aneurysm and AVM Foundation. All Rights Reserved)

Symptoms and Presenting Features

AVMs can present with a variety of symptoms depending on size, location, and if they have bled before. AVMs bleed, or hemorrhage, because of the abnormal vessels contained within the nidus (Fig. 9.2). These vessels cannot tolerate the high-pressure of blood flow from arterial feeding vessels and can rupture. Brain hemorrhage is the most common reason for patients with AVMs to seek medical attention. The most common age to bleed is between 15 and 20 years [2]. AVM hemorrhages can cause seizures, headache, neck stiffness, and symptoms of a stroke, such as weakness, numbness, and problems speaking, depending on the location within the brain (Fig. 9.3). In the worst scenarios, hemorrhages can cause coma or death. The exact risk of bleeding of brain AVMs is unknown, but believed to be between 2 and 4 % per year [3, 4]. The risk of bleeding may vary, depending on size and other features of the AVM [4, 5].

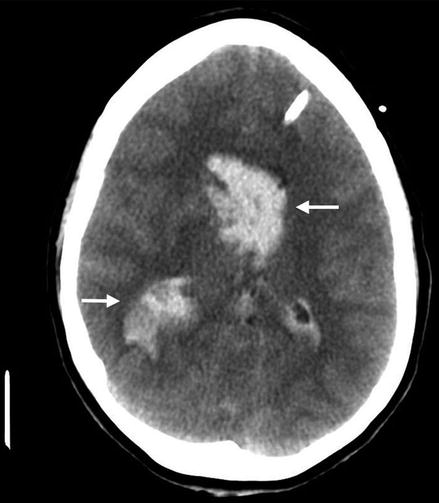

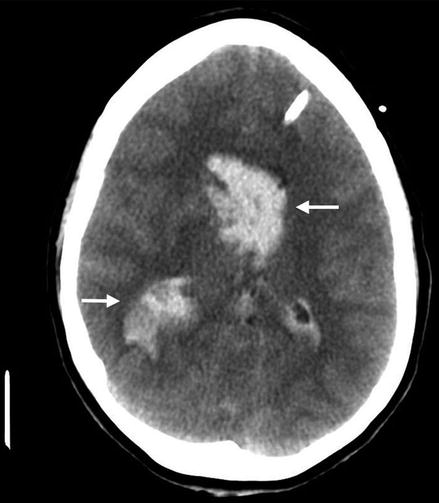

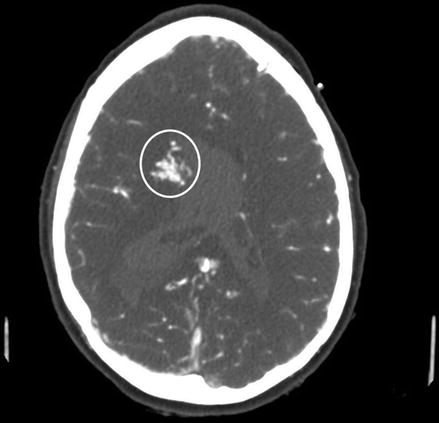

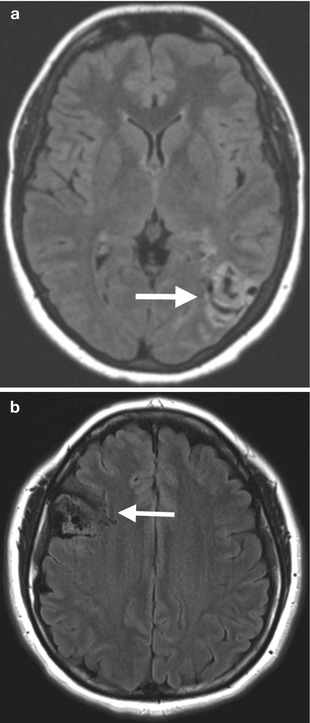

Figure 9.2

A CT scan of the head demonstrates hemorrhage from a brain AVM. The white arrows identify hemorrhage

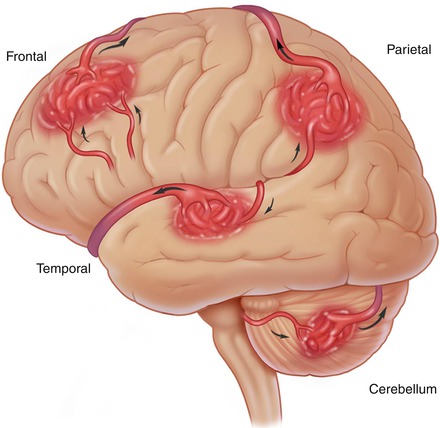

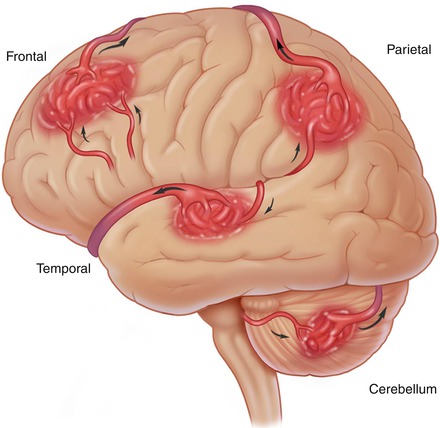

Figure 9.3

An illustration demonstrating the multiple locations brain AVMs can be found. AVM location is a critical factor in determining the possible risks of hemorrhage and risks from surgical removal (Courtesy, The Aneurysm and AVM Foundation. © 2013 The Aneurysm and AVM Foundation. All Rights Reserved)

Seizure without hemorrhage is the second most common symptom leading to medical evaluation. A seizure results from abnormal electrical activity in the brain. A seizure can take a variety of forms including involuntary movements, altered level of consciousness, or muscle stiffness. Following a seizure the patient may be confused or sleepy. This is typically transient and will improve with time. The younger a patient is at diagnosis of the AVM, the more likely they will go on to develop seizures [3]. As many as 30 % of patients with AVMs may require treatment for seizures.

Individuals with these lesions may seek medical attention for a variety of other symptoms. Symptoms of increased brain pressure may develop including nausea, vomiting, headaches, and coma. Other patients may experience symptoms of stroke, or brain ischemia. This typically results from the AVM “stealing” or shunting blood away from normal brain tissue. This is often reversible. A more benign presenting symptom is a bruit caused by increased blood flow. In these cases, patients may complain of hearing a “whooshing” sound.

Diagnosis

Initially, emphasis is placed on previous medical history and physical examination in those seeking medical attention. This will guide the clinician to order the appropriate studies. In an emergency setting a computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain is obtained to look for evidence of bleeding. This technology utilizes “x-rays” to take snapshots of the body in cross sections. CT scans can be used to provide information about the vasculature by means of an intravenous dye called CT angiography (CTa) (Fig. 9.4). CT scans do have limitations in revealing details of the brain and requires exposure to radiation. In the setting of an AVM, it will allow doctors to identify bleeding, its source, and location, and it can be performed in conjunction with a CTa. Depending on the results, further diagnostic imaging studies may be obtained. This includes a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain (Fig. 9.5). This imaging modality has the benefit of avoiding radiation and providing greater detail of the brain. This technology uses magnetic fields to differentiate different aspects of tissues. MRI has acquired new applications since its inception, and magnetic resonance angiography (MRa) can be performed. Similar to CTa, MRa provides information about the blood vessels of the brain (Fig. 9.6). Information obtained from these studies will guide your physician in determining further evaluation or treatment.

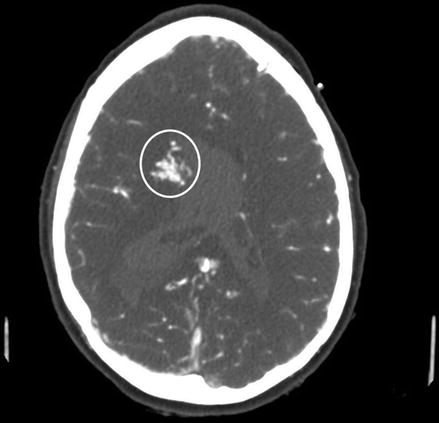

Figure 9.4

A CTa of the head demonstrates an AVM nidus (within the white circle) that is found as it takes up the contrast dye given intravenously and appears white on CTa

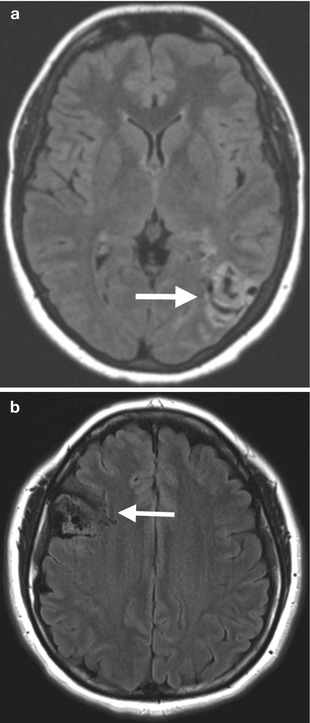

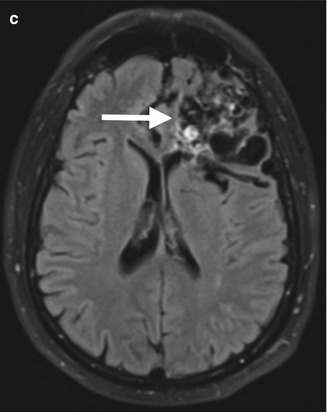

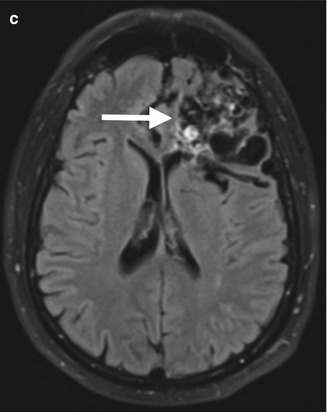

Figure 9.5

MR images (a–c) of three different patients with brain AVMs in different locations and sizes. The AVM nidus is demarcated by a white arrow

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree