Fig. 12.1

Sagittal T1-weighted MRI shows posterior longitudinal ligament elevation (arrow) and marked enhancement of disk and vertebral end plate after gadolinium administration

Fig. 12.2

(a, b) Sagittal T1-weighted MRI shows enhancement at the anterior surfaces of L3 and L4 vertebrae extending through the adjacent L3-4 disk space after gadolinium administration (Courtesy of O. Tuncyurek, M.D.)

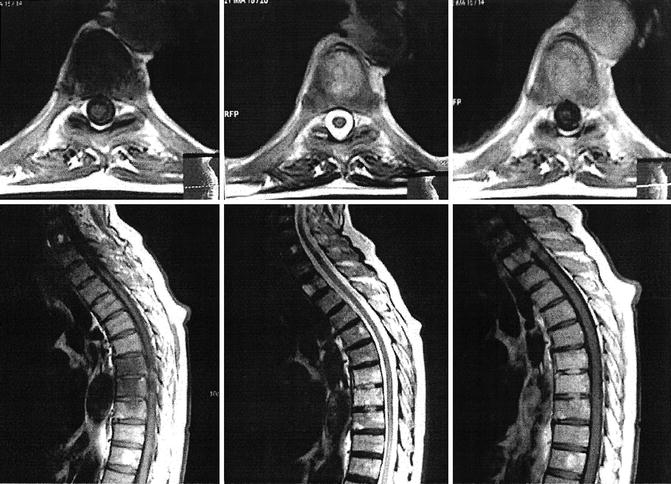

Fig. 12.3

MRI of a 77-year-old man with brucellar discitis and spondylitis, misdiagnosed as spinal metastasis with unknown origin. Axial and sagittal T1-and T2-weighted images demonstrate a contrast-enhanced infectious lesion involving the intervertebral spaces of T6-T7 and T7-T8, in addition to the vertebral bodies of T6 and T7 (From Turgut et al. [35], with permission)

Fig. 12.4

MRI of a 69-year-old woman with brucellar spondylodiscitis. Midsagittal T2-weighted image reveals high signal intensity at T12 and L1 levels and medullar compression by the T12 pedicle (Courtesy of A. Cervan, M.D.)

Bone scan is very sensitive in the early stage despite being nonspecific and also fails to demonstrate the extent of the lesion appropriately [6, 27]. At present, it is demonstrated that positron emission tomography (PET)-CT scan may provide useful information in the management of brucellar spondylodiscitis. In a recent review, the clinical impact of this technique in diagnosing spinal infections, with sensitivities ranging from 94 to 100 % and specificities ranging from 87 to 100 %, was emphasized [36]. In addition, PET-CT was reported in a recent retrospective study to have a significant role in the clinical management of 52 % of patients with infectious spondylitis. However, the utility of PET-CT in monitoring the efficacy of treatment was less clear because only one patient had a negative PET-CT, whereas four patients had a negative MRI of the affected spine at the end of treatment [18]. Importantly, a significant decrease was detected in maximum standardized uptake value (SUVmax) by means of a successful treatment, whereas patients without any residual MRI findings had significantly lower SUVmax compared to those having residual MRI findings. Virtually negative indices of inflammation were detected in all patients after a successful treatment, as expected. In general, MRI should be the preferred imaging modality for the diagnosis of brucellar spondylodiscitis owing to its high sensitivity and specificity. Nevertheless, it should be kept in mind that it has several inherent technical limitations such as sensitivity to motion degradation implying that the patients with movement disorders may not be suitable candidates for the examination. Additionally, certain metallic implants are accepted to be a contraindication for this modality. Also, MRI cannot always help distinguish spondylitis from severe degenerative arthritis. Another challenge is that usually MRI scans only of the spinal region with the suspected target lesion are requested by the referring physicians. However, in a recently published series of patients with brucellar spondylodiscitis, a rate of 9 % of noncontiguous multifocal spinal involvement was detected which can be missed if only one spinal region is assessed. Therefore, in every case of suspected brucellar spondylitis, the entire spine should be evaluated with MRI, though this may be logistically challenging in the routine clinical practice [18].

12.6 Comparison of Tuberculous and Brucellar Spondylodiscitis

In a study with the purpose of comparison, the clinical, radiological, and prognostic features of spontaneous spondylodiscitis secondary to tuberculosis and brucellosis, some useful information was obtained [7]. According to the results of this study, the most important differential diagnosis is tuberculosis, in addition to the usual causes of vertebral osteomyelitis or septic arthritis [7]. This may have a significant impact on the therapeutic approach as well as the prognosis, given that several antimicrobial agents used to treat brucellosis are also used to treat tuberculosis. Septic arthritis in brucellosis starting with small pericapsular erosions progresses slowly. Anatomically, anterior erosions of the superior end plate in the vertebrae are typically the first features to become evident, with eventual involvement and sclerosis of the whole vertebra. Anterior osteophytes eventually develop, though vertebral destruction or impingement on the spinal cord is rare and usually suggestive of tuberculosis.

12.7 Treatment of Spinal Brucellosis

Treatment for brucellar spondylitis should consist of two antibiotic agents for at least 12 weeks [2, 29]. Patients with brucellar spondylitis appear to respond better to doxycycline (100 mg orally twice daily for 12 weeks) plus streptomycin (1 g intramuscularly once daily for the first 14–21 days) than to doxycycline-rifampin [2]. Alternative choices include doxycycline (100 mg orally twice daily) plus rifampin (600–900 mg (15 mg/kg) once daily) for at least 12 weeks or ciprofloxacin (500 mg twice daily) plus rifampin for at least 12 weeks [2, 3, 29].

The duration of therapy is at least as important as the choice of antimicrobial agents [25]. In one meta-analysis, the failure rate for patients treated less than 6 weeks was 43 %; the failure rate for patients treated more than 12 weeks was 17 % [25].

In a study in Greece, the standard treatment of brucellar spondylitis with a combination of two antibiotics for 6–12 weeks is associated with high rates of treatment failure and relapse [19]. A total of 18 patients with brucellar spondylitis were treated with a combination of at least three suitable antibiotics: doxycycline, rifampin, plus intramuscular streptomycin or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMX, co-trimoxazole) or ciprofloxacin until the completion of at least 6 months of treatment [19]. If required, the treatment was continued with additional 6-month cycles, until resolution or significant improvement of clinical and radiological findings, or for a maximum of 18 months [19]. During the follow-up period with a mean of 36.5 months ranging from 1 to 96 months, no relapses were observed [19].

As a final management option, diagnostic or curative surgery can be performed in spinal brucellosis. Surgical intervention should be preferred when spinal instability, cord compression, radiculopathy, cauda equine syndrome, and severe weakness of the muscles due to extradural inflammatory mass or progressive collapse are present [11, 24, 31, 33].

Alternatively, percutaneous drainage or aspiration of epidural and paravertebral abscesses can be performed rather than surgery [33]. Nevertheless, abscess drainage is not always mandatory in the absence of neurological deterioration, and medical management can provide cure as well. Furthermore, analgesics and immobilization with orthosis as supportive management tools can be helpful to reduce the pain associated with spinal brucellosis [1, 27].

In spinal brucellosis, delayed convalescence after treatment is a well-known clinical sequela. Although the exact mechanism for this condition is not clearly understood, psychoneurosis exacerbated by the infection has been proposed as a causative factor for the delay. Clinically, this sequela is considered when pain, abnormal physical findings, or functional limitation persist for longer than 6 months in the posttreatment period. The severity of this clinical sequela may be mild, moderate, and severe depending on the patient’s functional condition. Accordingly, the sequela is accepted as mild if no neurological deficits remain, but the patient suffers from pain during exercise which does not interfere with work. The sequela is considered as moderate if pain interferes with work or milder motor or sensorial deficits remain, whereas permanent and excruciating pain requiring rest and analgesics or remaining motor or sensorial deficits imply severe form of sequela. Anti-inflammatory drugs can be helpful for the treatment of mild clinical sequela, whereas the presence of moderate or severe sequelae may necessitate surgery [24, 31].

The early diagnosis, the administration of appropriate antimicrobial treatment, and the control of animal infection in endemic regions is crucial for the prevention of spinal brucellosis. Bone and joint involvement and epididymo-orchitis are considered the most frequently encountered complications of brucellosis [28]. Relapse of brucellosis is frequently detected owing to the fact that it is an intracellular organism.

Apparently, the diagnosis requires a high degree of clinical suspicion and thorough occupational and travel history. Nevertheless, a definitive diagnosis of the disease requires isolation of Brucellae spp. from blood cultures and bone marrow samples and demonstration of antigens and antibodies to Brucella by serological tests.

Importantly, brucellosis can be prevented mainly by increasing public awareness to safe livestock practices and mass vaccination of animals. Classically, the treatment recommended by the World Health Organization for acute brucellosis in adults is rifampicin 600–900 mg and doxycycline 100 mg twice daily for a minimum of 6 weeks [28]. Combined use of intramuscular streptomycin (1 g daily for 2–3 weeks) and an oral tetracycline (2 g daily for 6 weeks) results in fewer relapses [28]. Tetracycline monotherapy for a duration of 6 weeks may be considered as a good treatment option for patients with brucellosis with no focal disease, and a low risk of patients with focal disease, such as endocarditis or spondylitis, may require administration of extended courses of antibiotics [28]. Surgery should be preferred for patients with endocarditis and cerebral or hepatosplenic abscess that are antibiotic resistant [28].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree