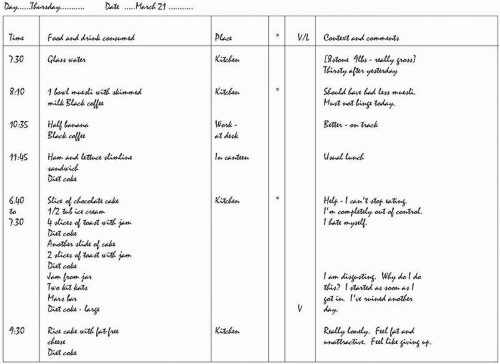

(a) Dieting and binge eating

The eating habits of patients with bulimia nervosa are characterized by strict dieting punctuated by repeated episodes of binge eating (see

Fig. 4.10.2.2). The dieting is extreme and it is governed by multiple self-imposed dietary rules. These rules tend to be applied to all aspects of eating, including when to eat, what to eat, and how much to eat. As a result, the food eaten (when not binge eating) is restricted in quantity and range.

Recurrent episodes of ‘binge eating’ interrupt this dieting. (The term binge eating denotes discrete episodes of eating that have two characteristics: first, an unusually large amount of food is eaten,

given the circumstances; and second, there is a sense of loss of control at the time. Some patients with eating disorders have similar episodes of uncontrolled overeating that do not involve the consumption of objectively large amounts of food. These episodes are sometimes referred to as ‘subjective binges’ although technically speaking they do not meet the definition of a ‘binge’.) The frequency and regularity of the binge eating varies. Some patients have episodes almost every day, whereas in others the episodes are intermittent. In DSM-IV, it is specified that the binges should occur on average at least twice a week, but this is an arbitrary figure that has little discriminatory value. Among those patients in whom the binge eating is frequent, the binges have few, if any, obvious triggers, although there may be circumstances under which binge eating is more likely (for example, when alone at home). Among patients in whom the binge eating is less frequent, the binges often have clear precipitants. These tend to be of three overlapping types: first, there is breaking a personal dietary rule (for example, exceeding a daily calorie-limit or eating a banned food); second, there are situations which intensify concerns about shape and weight (for example, receiving an adverse comment about appearance); and third, there is the occurrence of negative moods (often as a result of interpersonal events). All three undermine the maintenance of strict dietary control.

The amount of food eaten during binges varies, both from patient to patient and from episode to episode. Typical episodes involve the consumption of 1000 to 2000 kcal.

(9) The food eaten generally comprises items that are otherwise being avoided. Thus binges tend to be composed of energy-dense, high-fat items such as chocolate, ice cream, and pastries. Binges come to an end as a result of the combined influence of exhaustion, extreme fullness, a diminution of the drive to eat, and the running out of food supplies. In about three-quarters of patients they are immediately followed by measures designed to counteract the effects of the overeating, the most common being self-induced vomiting and the taking of laxatives or diuretics.

The binges are a source of considerable distress. They magnify these patients’ fears of weight gain and fatness, and they may result in shame and self-disgust. For this reason most binges occur in private and are kept secret from others. It is the binge eating that eventually drives these people to seek help.

(b) Purging and other forms of weight control

In DSM-IV bulimia nervosa is subdivided into two types, a purging and non-purging type. In the purging type there is regular self-induced vomiting or the misuse of laxatives or diuretics, or both, whereas in the non-purging type such behaviour (‘purging’) is either not present or it is infrequent. The majority of patients seen in clinical practice have the purging form of the disorder and it has been the focus of most research.

Self-induced vomiting is the most common form of purging. In most patients it only takes place after binge eating. It is generally achieved by stimulating the gag reflex, using the fingers or some

other long object, although in more established cases it can be accomplished with no mechanical aid. The vomiting is repeated until patients think that they have retrieved all the food that they can. Patients get extremely distressed if they are unable to vomit after binge eating: indeed, if they foresee that they may not have the opportunity to vomit, they tend not to binge. A minority of patients also induce vomiting at other times, for example, following smaller episodes of overeating (subjective binges) or ordinary meals or snacks.

The misuse of laxatives or diuretics is somewhat less common than self-induced vomiting. It takes two forms: one is to compensate for specific episodes of binge eating, like self-induced vomiting; and the other is as a general method of weight control (like dieting), in which case it is not tied to particular episodes of overeating. The number of laxatives or diuretics taken varies considerably, sometimes far exceeding the recommended dose.

None of these methods of purging is an effective method of weight control. Self-induced vomiting results in the retrieval of only about half to two-thirds of what has been eaten, the taking of laxatives has a minimal effect on food absorption, and diuretictaking has none. As a result, a significant proportion of each binge is absorbed.

The weight of most of these patients is in the healthy range (BMI between 20 and 25) due to the effects of the under-eating and overeating cancelling each other out. As a result they do not experience the secondary psychosocial and physical effects associated with maintaining a very low weight seen in anorexia nervosa.

Other forms of weight-control behaviour are practised by some patients, including over-exercising, the spitting out of food, and the taking of repeated enemas or saunas. Over-exercising is the most common of these, but it is not nearly as prominent or as obviously pathological as in anorexia nervosa. A minority of patients ruminate, that is, repeatedly regurgitate and re-chew food that has been eaten. They may then either re-swallow the food or spit it out. This behaviour is not well-understood.

In the non-purging type of bulimia nervosa there is no vomiting or misuse of laxatives or diuretics, or they occur infrequently. Instead, there is sustained and marked dietary restriction outside the binges. This is both a response to the binge eating and contributor to it, in that this type of eating increases the risk of further episodes. In all other respects the two subtypes of the disorder are similar.

(c) Attitudes to shape and weight

A characteristic set of attitudes to shape and weight is the other distinctive element of the specific psychopathology of bulimia nervosa. Equivalent attitudes are found in anorexia nervosa and most cases of eating disorder NOS. These attitudes are often described as the ‘core psychopathology’ of eating disorders. They are characterized by an overconcern with shape and weight in which there is a fear of weight gain and fatness that is generally accompanied by a pursuit of weight loss and thinness. Underlying this psychopathology is the tendency to judge self-worth largely, or even exclusively, in terms of shape and weight. Whereas it is usual to evaluate self-worth on the basis of perceived performance in a variety of domains of life (such as interpersonal relationships, work, sport, artistic ability, etc.), people with anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa evaluate themselves primarily in terms of their shape and weight. These attitudes and values constitute a good example of an overvalued idea.

Most features of bulimia nervosa can be understood as being secondary to these attitudes to shape and weight. The dieting, purging, and over-exercising are obvious secondary features. In addition, there are direct behavioural expressions of these concerns. For example, many patients repeatedly weigh themselves and scrutinize their appearance in mirrors. Others avoid any knowledge of their weight while being acutely sensitive about their appearance. Some avoid others seeing their body and some even avoid seeing it themselves. This can have a major impact on social and sexual relationships.

The concerns about shape and weight, and eating, have a major effect on others in the patient’s immediate environment. Meals are often times of tension and social events which involve eating may be avoided. The feeding of children may be affected

(10) and their growth may be impaired

(11) (see

Chapter 9.3.6).